Contact with the youth justice system

The majority of children and young people in WA have little or no contact with the youth justice system. However, there is a small cohort of children and young people who experience significant challenges and disadvantage, which can lead them into regular or ongoing contact with the justice system. Ensuring the wellbeing and rehabilitation of this group of young people is vital.

The personal, economic and social costs of not addressing the underlying causes of offending for these young people and the wider community are significant.1,2 It is essential that coordinated early intervention and the delivery of therapeutic programs and supports to address the underlying causes of offending are implemented to divert children and young people away from the justice system.

Last updated June 2020

Overview

Most children and young people in WA have little or no contact with the youth justice system. For those who do, a variety of responses are available ranging from diversionary options to juvenile justice supervision through community-based sentencing or detention.

In 2018–19, there were approximately 5,989 children and young people aged 10 to 17 years who were proceeded against by the WA Police Force (WA Police) for allegedly committing an offence. This represents 2.3 per cent of the total population of WA’s children and young people aged 10 to 17 years (approximately 257,000 in 2019).

Areas of concern

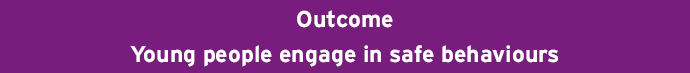

WA Police has the highest rate of proceeding against1 children and young people aged 10 to 14 years compared to other jurisdictions in Australia. It should be noted that these proceedings can be oral cautions.

Children and young people aged 10 to 14 years who allegedly committed an offence by jurisdiction, rate, Australia, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19, Table 15 Offenders, Sex by age, States and territories, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Most children and young people under 14 years of age are not sentenced to detention, yet 143 children and young people aged 10 to 13 years spent time in unsentenced detention during 2018–19.

Unsentenced Aboriginal children and young people in WA spent an average of 46 days in detention and unsentenced non-Aboriginal children and young people in WA spent an average of 25 days.

In 2016–17, 56.2 per cent of children and young people released from sentenced supervision in WA returned within 12 months.

Endnotes

- A proceeding is a legal action initiated against an alleged offender for an offence(s). Legal actions can be court actions (laying charges) or non-court actions (diversions, infringements, warnings). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19.

Last updated June 2020

This measure is intended to report the experiences of those children and young people who are engaged in violent or antisocial1 behaviour.

Reliable data that provides information about the extent to which WA young people engage in violent and antisocial behaviour is limited. There is also little data on WA children and young people’s personal experiences of participating in violent or antisocial behaviours.

A range of interrelated social and environmental factors including family and community dysfunction and violence, social exclusion and poverty, disengagement from education and alcohol and drug use contribute to children and young people’s likelihood of engaging in violent and antisocial activities.2,3,4

Recent Australian research found that 75.0 per cent of justice-involved young people had experienced some form of non-sexual abuse, 44.0 per cent had had at least one head injury including a loss of consciousness, and significant proportions reported high or very high levels of psychological distress (54.0% of female justice-involved young people and 33.0% of male justice-involved young people).5 Furthermore, ‘rates of having ever attempted suicide were nearly six times as high among justice-involved young people compared with their peers in the general population’.6

Furthermore, young people in their teenage years have an increased risk of engaging in aggressive, illegal and risky behaviours as their ability to control their impulses and behaviours is still developing, while at the same time they are experiencing the intense and changing emotions related to the transition to adulthood.7

Preventing children and young people from engaging in violent and antisocial behaviour and improving the outcomes for those who do, is critical. There is considerable evidence to show that the economic and social costs of not acting early are significant.8,9 These include future expenditure on school disengagement and unemployment, poor physical and mental health, drug and alcohol misuse, welfare support and criminal justice.10 Intervening early reduces the personal impact on the children and young people, supporting them to live a healthy, safe and productive life.

In 2016 the Commissioner spoke to 92 children and young people aged 10 to 19 years who had contact with the WA youth justice system to better understand the unique challenges and issues they encounter that impact their wellbeing and healthy development to adulthood.11

Five key themes emerged from participants’ responses regarding why young people get into trouble (in order of frequency):

- problems with family,

- friends who were involved in criminal behaviour,

- disengagement from school,

- disconnection from the broader community,

- personal issues including, crime as a normal habit, drug and alcohol use, cognitive disorders and mental health issues.

Family was the most commonly cited reason and this included families being engaged in criminal activity, alcohol, drug and mental health issues, and violence in the home.12

For more information refer to:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Speaking Out About Youth Justice, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Endnotes

- Antisocial behaviour is broadly defined as behaviour which ‘infringes upon accepted societal norms or laws, including acts of vandalism, verbal or physical assault, theft, and other behaviours detrimental to the maintenance of safety and social order’. Hemphill SA et al 2017, Positive associations between school suspension and student problem behaviour: Recent Australian findings, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, No. 531, Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Gilmore L 1999, Pathways to prevention: Developmental and early intervention approaches to crime in Australia, National Crime Prevention, Attorney General’s Department, pp.7-10.

- Baldry E et al 2018, ‘Cruel and unusual punishment’: an inter-jurisdictional study of the criminalisation of young people with complex support needs, Journal of Youth Studies, Vol 21, No 5.

- Malvaso C 2017, Investigating the complex links between maltreatment and youth offending, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Muerk C et al 2019, Changing Direction: mental health needs of justice-involved young people in Australia, Kirby Institute, UNSW, p. 4.

- Ibid.

- Modecki K et al 2018, Antisocial behaviour during the teenage years: Understanding developmental risks, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice, No 556, Australian Institute of Criminology.

- CoLab – Collaborate for Kids et al 2019, How Australia can invest in children and return more, A new look at the $15b cost of late action, CoLab – Collaborate for Kids, p. 5.

- Fox S et al 2015, Better Systems, Better Chances: A Review of Research and Practice for Prevention and Early Intervention, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY), p. 35.

- Fox S et al 2015, Better Systems, Better Chances: A Review of Research and Practice for Prevention and Early Intervention, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY), p. 3.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Speaking Out About Youth Justice, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid, p. 7-8.

Last updated June 2020

Children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years who have, or are alleged to have, committed an offence can be detained and held in police custody.

Children and young people are particularly vulnerable during periods in which they are held in police custody. This vulnerability can be exacerbated by the traumatic or distressing circumstances that frequently precede arrest and detention as well as the varying risk factors to which these young people are predisposed.

Section 7 of the Young Offenders Act 1994 states that detaining a child or young person ‘should only be used as a last resort and, if required, is only to be for as short a time as is necessary’.1 It also states that if a child or young person is required to be detained, it should be in a facility that is suitable for them and they should not be exposed to contact with any adult detained in the facility. There are exceptions for young people over the age of 16 years.

It is recognised that the facilities in police custody (e.g. lock-ups) are generally not suitable for children and young people and if they are required to be detained for a longer period they should be transferred to a detention centre (Banksia Hill Detention Centre in Perth).2 Wherever possible, children and young people who are detained should be granted bail and released to a responsible adult, without the need for a significant time spent in custody or transfer to Banksia Hill Detention Centre.

Children and young people can be held in police custody3 for a variety of reasons including, but not limited to, the following:

- they have been charged with an offence, granted bail and are being held until a responsible adult can be found to collect them

- they have been charged with an offence, have not been granted bail and are awaiting transfer to Banksia Hill for remand

- WA police have picked them up as they had reasonable grounds to believe there was a risk to their safety and welfare.4,5

Children and young people in regional and remote WA are more likely to be held in police custody for longer periods of time as they may be awaiting transport to a larger regional town and/or flights to the Banksia Hill Detention Centre in Perth.6,7 This disproportionately affects Aboriginal children and young people as greater proportions of Aboriginal children and young people live in regional and remote WA.

Children and young people can also be held in custody for a longer period of time due to an inability to find a responsible adult to collect them.8 This is more likely to occur in the metropolitan area, as in regional and remote areas WA police are more familiar with the young people’s families.9

There is no publicly available data on children and young people held in police custody in WA.

Strip searches during a custody episode

Section 135 of the Criminal Investigation Act 2006 provides authorised officers with a specific power to search certain persons who are in police custody for security risk items. This power is not restricted to adults and includes children and young people over 10 and under 18 years of age.

A ‘strip search’ is defined according to the Criminal Investigation Act 2006, (CIA), where an authorised officer may do any or all of the following: remove any article that the person is wearing including any article covering their private parts, search any article removed, search the person’s external parts including their private parts, search the person’s mouth but not any other orifice.10

There are additional rules for doing strip-searches including that the searcher must be the same gender as the person being searched.11 There are no additional rules for searching children and young people.

In 2018–19, 1,450 strip searches were conducted on WA children and young people under 18 years of age during a custody episode. This is a reduction of 417 searches from the previous year.

|

Number |

|

|

2014–15 |

1,056 |

|

2015–16 |

1,203 |

|

2016–17 |

1,456 |

|

2017–18 |

1,867 |

|

2018–19 |

1,450 |

Source: Parliamentary debates (Hansard): Legislative Council, 4 December 2019, Response of the Honourable Stephen Dawson MLC to questions on numbers of strip searches from the Honourable Alison Xamon MLC

|

Male |

Female |

Total* |

|

|

10 years |

18 |

** |

19 |

|

11 years |

23 |

** |

24 |

|

12 years |

55 |

13 |

68 |

|

13 years |

97 |

41 |

138 |

|

14 years |

174 |

63 |

237 |

|

15 years |

204 |

61 |

267 |

|

16 years |

287 |

60 |

348 |

|

17 years |

266 |

80 |

349 |

|

Total |

1,124 |

320 |

1,450 |

Source: Parliamentary debates (Hansard): Legislative Council, 4 December 2019, Response of the Honourable Stephen Dawson MLC to questions on numbers of strip searches from the Honourable Alison Xamon MLC

* Total includes children and young people who did not identify as either male or female and therefore does not sum.

** Values have been suppressed for confidentiality purposes.

Of the strip searches in 2018–19, 19 searches were on children who were 10 years old, 24 on 11-year-old children and 68 on 12 year-old children. There were 15 strip searches conducted on female children under 13 years of age and 96 strip searches conducted on male children under 13 years of age.

Six of the searches were on young people who identified as trans.12

No information is publicly available on the proportion of strip-searches that resulted in security risk items being found.

WA Police also have the legislative authority to conduct non-custodial strip searches, however, there is no systematic recording practice and therefore these cannot be reliably identified. As a result, searches outside of custody are not included in this data.13

Self-harm or suicide of children and young people while in police custody

Children and young people, particularly Aboriginal children and young people, in police custody or detention are at risk of self-harm or attempted suicide.14,15

There is limited publicly available data on the number of incidents of self-harm, attempted suicide or suicide of children and young people held in police custody.

|

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

Incidents of self-harm/attempted suicide |

35 |

66 |

Source: Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Legislative Council, 3 September 2019, Response of the Honourable Stephen Dawson MLC to questions on incidents of self-harm and attempted suicides from the Honourable Alison Xamon MLC

Notes:

1. The WA Police Custodial Management System does not distinguish between incidents of self-harm and an incident of attempted suicide.

2. Figures are subject to revision. Self-harm incidents include those which are recorded as “attempted”, “actual” or “threatened”. A self-harm incident is determined based on an event either being recorded as a “detainee self-harm” event or being recorded as an “other” event and containing terms in the incident narrative which indicate self-harm behaviour. Self-harm incident counts are based on the number of events and means that where multiple incidents have occurred during a single custodial episode, each incident is counted.

No further information is publicly available on the number of children and young people involved in the above incidents, the age of the children and young people or their Aboriginal status.

Endnotes

- Section 7(h) of the Young Offenders Act 1994.

- Section 19(2) of the Young Offenders Act 1994.

- Police custody can occur both within a WA Police custodial facility and in other field locations (e.g. residential and business addresses).

- Sections 37 and 41 of the Children and Community Services Act 2004.

- WA Auditor General 2008, Performance Examination: The Juvenile Justice System: Dealing with Young People under the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 41-42.

- Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2011, Review of Regional Youth Custodial Transport Services in Western Australia, WA Government, p. 5.

- Richards K and Renshaw L 2013, Bail and remand for young people in Australia: A national research project, Australian Institute of Criminology, p. 71.

- WA Auditor General 2008, Performance Examination: The Juvenile Justice System: Dealing with Young People under the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 44.

- WA Auditor General 2008, Performance Examination: The Juvenile Justice System: Dealing with Young People under the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 45.

- Section 64 of the Criminal Investigation Act 2006.

- Section 72 of the Criminal Investigation Act 2006.

- Parliamentary debates (Hansard): Legislative Council, 4 December 2019, Response of the Honourable Stephen Dawson MLC to questions on numbers of strip searches from the Honourable Alison Xamon MLC.

- Parliamentary Debates - Hansard: Legislative Council, 4 December 2019, reply by the Honourable Stephen Dawson

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) National data on the health of justice-involved young people: a feasibility study 2016–17, AIHW, p. 5.

- Borschmann R et al 2014, Self-Harm in Young Offenders, Suicide & life-threatening behaviour, Vol 44, No 6.

Last updated June 2020

Children and young people first enter the youth justice system when they are investigated by police for allegedly committing an offence. Legal action taken by police may include court actions (charging them with an offence) and non-court actions (such as cautions, counselling, or infringement notices).1

Children and young people aged 10 to 17 years can be charged under the WA Criminal Code. The Australian and New Zealand Children’s Commissioners and Guardians (ANZCCG) recommend governments in Australia and New Zealand raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 years, consistent with international standards.2 Children who come into contact with the justice system before 14 years of age are less likely to complete their education or find employment and are more likely to reoffend and move into the criminal justice system as adults.3

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) annually reports on the offender numbers and rates for alleged young offenders aged 10 to 17 years who have been proceeded against (both court and non-court actions) by police.4

In 2018–19, there were 5,989 children and young people aged 10 to 17 years who were proceeded against for one or more offences in WA. This represents approximately 2.3 per cent of the population of WA’s children and young people aged 10 to 17 years (257,000).5 Most of these children and young people have only one or two contacts with police for low-level offences which result in cautions or infringements.6

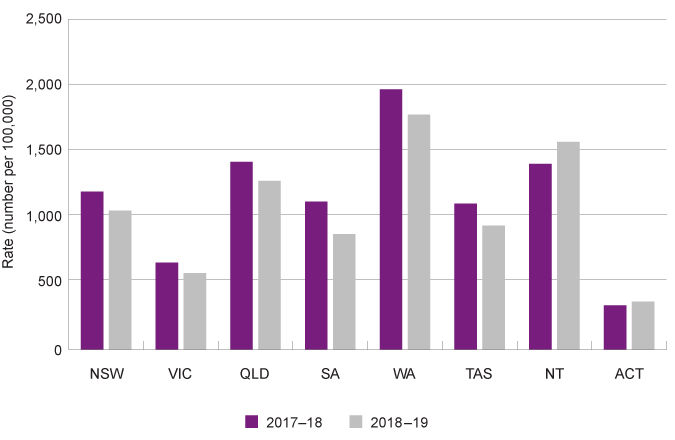

The number of children and young people aged 10 to 17 years alleged to have committed offences in WA decreased from 2012–13 to 2018–19. The offender rate has also decreased over that period.

|

Number |

Offender rate |

|

|

2012–13 |

7,214 |

2,968.6 |

|

2013–14 |

6,469 |

2,658.0 |

|

2014–15 |

6,357 |

2,609.2 |

|

2015–16 |

6,466 |

2,642.7 |

|

2016–17 |

6,593 |

2,665.2 |

|

2017–18 |

6,577 |

2,621.5 |

|

2018–19 |

5,989 |

2,349.2 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018–19, Table 20 Youth Offenders, Principle offence, States and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19

Notes: Offender rates are expressed as the number of children and young people per 100,000 of the relevant Estimated Resident Population (ERP).

Children and young people aged 10 to 17 years proceeded against for one or more offences, number and number per 100,000, WA, 2012–13 to 2018–19

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018–19, Table 20 Youth Offenders, Principle offence, States and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19

Across Australia, male children and young people were more likely to be proceeded against than female children and young people (2,757.5 per 100,000 male children and young people compared to 1,285.0 female children and young people).

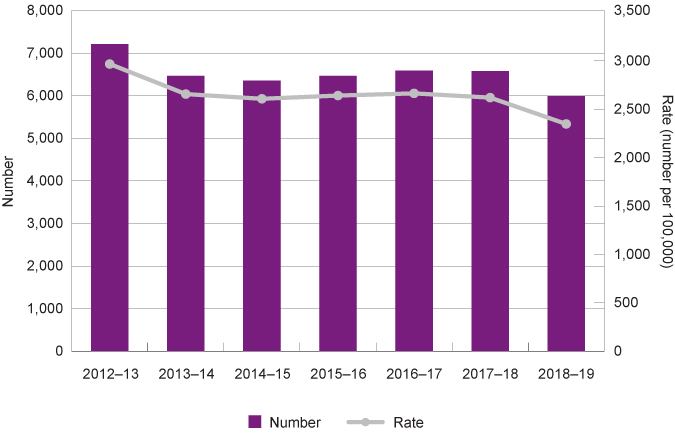

In 2018–19, the youth offender rate decreased for all Australian jurisdictions, except the Northern Territory. The WA youth offender rate decreased from 2,621.5 alleged offenders per 100,000 children and young people in 2017–18 to 2,349.2 alleged offenders per 100,000 children and young people in 2018–19.

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

NSW |

2,745.0 |

2,766.2 |

2,729.5 |

2,678.6 |

2,371.9 |

|

QLD |

2,649.7 |

2,618.5 |

2,542.8 |

2,427.5 |

2,259.0 |

|

WA |

2,609.2 |

2,642.7 |

2,665.2 |

2,621.5 |

2,349.2 |

|

TAS |

2,339.9 |

2,237.0 |

2,053.6 |

2,075.9 |

1,774.9 |

|

NT |

3,074.9 |

3,482.5 |

2,961.3 |

2,815.6 |

2,963.7 |

|

ACT |

1,009.4 |

1,161.1 |

883.9 |

869.6 |

792.1 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018–19, Table 20 Youth Offenders, Principle offence, States and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19

* Data is not presented for Victoria or South Australia as the reported data for Victoria was for selected principal offences only and South Australian data for 2018–19 not comparable with earlier reference periods.

Note: Rate is per 100,000 persons aged 10 to 17 years for the state/territory of interest.

Total offender rate of young people aged 10 to 17 years, number per 100,000, selected Australian jurisdictions, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018–19, Table 20 Youth Offenders, Principle offence, States and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19

Note: Data is not presented for Victoria or South Australia as the reported data for Victoria was for selected principal offences only and South Australian data for 2018–19 not comparable with earlier reference periods. The ACT results are excluded from the graph as they have limited comparability.

The most common principal offence in WA was theft (457.8 per 100,000 young people) followed by acts intended to cause injury (451.9 per 100,000 young people) and unlawful entry with intent (413.0 per 100,000 young people).

|

Number |

Offender rate |

|

|

Theft |

1,167 |

457.8 |

|

Acts intended to cause injury |

1,152 |

451.9 |

|

Unlawful entry with intent |

1,053 |

413.0 |

|

Illicit drug offences |

689 |

270.3 |

|

Property damage and environmental pollution |

497 |

194.9 |

|

Public order offences |

465 |

182.4 |

|

Robbery/extortion |

245 |

96.1 |

|

Sexual assault and related offences |

211 |

82.8 |

|

Weapons/explosives |

160 |

62.8 |

|

Offences against justice |

122 |

47.9 |

|

Abduction/harassment |

109 |

42.8 |

|

Total* |

5,989 |

2,349.2 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018–19, Table 20 Youth offenders, Principal offence, States and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19

* Total does not sum as it includes other offences with lower offender rates.

Notes:

1. Rate is per 100,000 persons aged 10 to 17 years for the state/territory of interest.

2. WA Police applied a number of revisions to their offence coding in the 2017–18 and 2018–19 data for national statistical purposes. This impacts on a range of offences and results in the data by offence being not comparable to previous reference periods.

The most common principal offence for a 10 year-old alleged offender in Australia was unlawful entry with intent, while the most common principal offence for a 17 year-old alleged offender was illicit drug offences.7

Almost one-half (2,873 or 48.0%) of the children and young people proceeded against by WA Police in 2018–19 were aged between 10 and 14 years.

WA has the highest rate of proceeding against children and young people aged 10 to 14 years compared to other jurisdictions in Australia. It should be noted that these proceedings can be oral cautions.

|

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

NSW |

1,176.1 |

1,034.0 |

|

VIC |

647.5 |

569.1 |

|

QLD |

1,397.8 |

1,257.1 |

|

SA |

1,101.5 |

858.6 |

|

WA |

1,938.7 |

1,750.5 |

|

TAS |

1,087.4 |

921.7 |

|

NT |

1,383.8 |

1,547.2 |

|

ACT |

328.6 |

355.9 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19, Table 15 Offenders, Sex by age, States and territories, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Note: Rate is the number of children and young people per 100,000 of the specified population.

Children and young people aged 10 to 14 years who allegedly committed an offence by jurisdiction, rate, Australia, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19, Table 15 Offenders, Sex by age, States and territories, 2017–18 to 2018–19

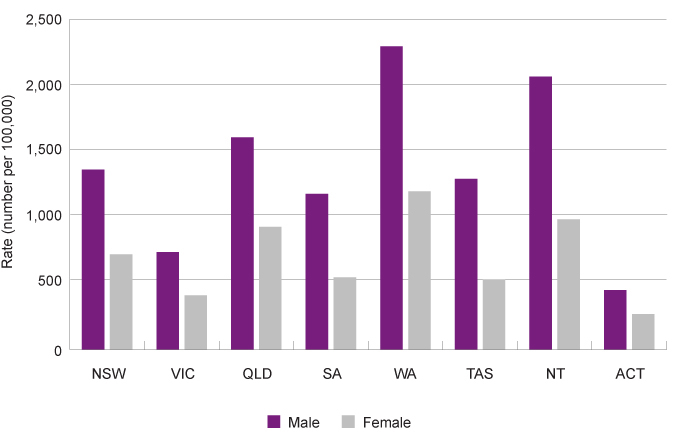

Male and female children and young people aged 10 to 14 years are both more likely to be proceeded against by WA Police than children and young people of that age and gender in any other Australian jurisdiction.8

|

Male |

Female |

|||

|

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

|

|

NSW |

1,339.3 |

6,390.2 |

709.1 |

2,648.1 |

|

VIC |

724.3 |

4,285.5 |

402.8 |

1,359.2 |

|

QLD |

1,581.2 |

6,641.4 |

912.8 |

2,540.5 |

|

SA |

1,159.7 |

7,852.2 |

537.0 |

2,785.7 |

|

WA |

2,258.4 |

4,701.3 |

1,177.5 |

1,982.7 |

|

TAS |

1,272.0 |

6,596.5 |

521.5 |

2,508.5 |

|

NT |

2,032.9 |

10,537.6 |

968.7 |

3,484.2 |

|

ACT |

442.5 |

2,209.4 |

262.9 |

874.0 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19, Table 15 Offenders, Sex by age, States and territories, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Note: Rate per 100,000 persons aged 10 years and over for the state/territory, sex and age group of interest.

Children and young people aged 10 to 14 years who allegedly committed an offence by jurisdiction and gender, number per 100,000, Australia, 2018–19

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19, Table 15 Offenders, Sex by age, States and territories, 2017–18 to 2018–19

Diversions

When a child or young person comes into contact with WA Police for an alleged offence a decision is made to either direct them away from (diversion) or towards the court system.

The WA Young Offenders Act 1994 states that non-court actions should be preferred when dealing with young alleged offenders.9 Detention of children and young people should be used as a last resort and all possible efforts must be made to maximise diversion of children and young people who offend.

Diverting children and young people away from the court system reduces costs to the state and can reduce further offending by the children and young people.10

In WA not all offences are eligible for diversion. Certain offences are listed in Schedule 1 and 2 of the Young Offenders Act 1994 for which children and young people cannot be diverted. Furthermore, diversion options are only available where the young person accepts responsibility.

The most common diversionary approaches are a written caution, an oral caution, referral to the Juvenile Justice Team (JJT) or referral to a drug (cannabis) counselling program.

The 2017 Auditor General’s report Diverting Young People Away from Court found that police chose to divert eligible children and young people in less than half of cases.11 The Auditor General also reported that when WA Police made the decision not to divert a young person from court, they did not record the reasoning behind their decision and were therefore unable to gain an understanding of whether the decisions were appropriate or how to improve diversion rates.12

There is no publicly available data on diversions of children and young people in WA. The Commissioner for Children and Young People will work with WA Police to report data on this measure in the future.

Sentencing

If a young person, aged from 10 to 17 years, has been charged with an offence, they will generally appear in the Children's Court of WA. Children’s Court cases are usually held at the Perth Children's Court however, some Children’s Court cases are also heard in other courthouses throughout the State.

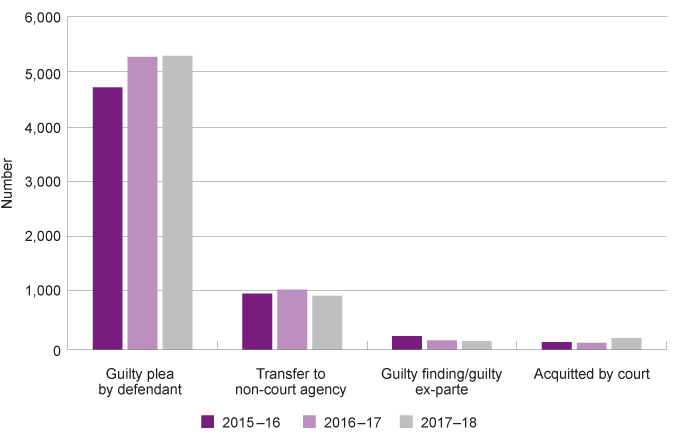

More than three-quarters (76.4% in 2017–18) of criminal cases that proceed to the Children’s Court are finalised by the child or young person pleading guilty.

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Guilty plea by defendant |

4,686 |

73.9 |

5,235 |

75.2 |

5,252 |

76.4 |

|

Transfer to non-court agency |

996 |

15.7 |

1,070 |

15.4 |

957 |

13.9 |

|

Guilty finding/guilty ex-parte |

236 |

3.7 |

161 |

2.3 |

149 |

2.2 |

|

Acquitted by court |

128 |

2.0 |

115 |

1.7 |

201 |

2.9 |

|

Other |

295 |

4.7 |

384 |

5.5 |

315 |

4.6 |

|

Total cases finalised |

6,341 |

100.0 |

6,965 |

100.0 |

6,874 |

100.0 |

Source: Department of Justice, Report on Criminal Cases in the Children's Court of Western Australia 2013/14 to 2017/18

Criminal cases finalised for children and young people aged 10 to 17 years by method of finalisation, number, WA, 2015–16 to 2017–18

Source: Department of Justice, Report on Criminal Cases in the Children's Court of Western Australia 2013/14 to 2017/18

Since 2015–16 there has been an increase in the number and proportion of cases finalised by the child or young person pleading guilty.

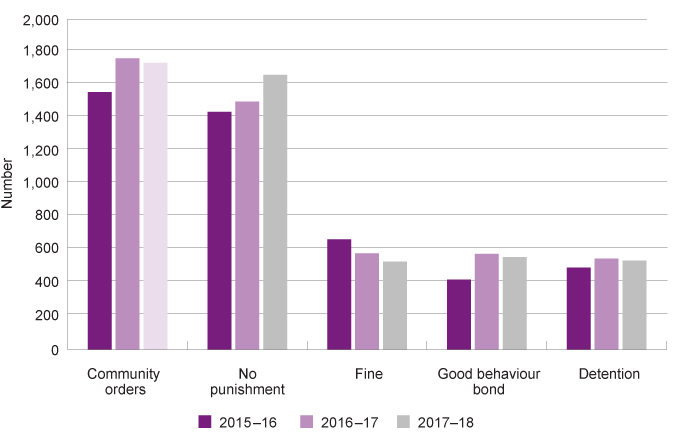

The most common sentence for cases finalised with a guilty finding is a community order (31.7% of sentences), which will usually have a community work component as well as a supervision component. A period of detention is imposed in just under 10 per cent of cases.

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Community orders* |

1,534 |

31.2 |

1,735 |

32.1 |

1,709 |

31.7 |

|

No punishment** |

1,417 |

28.8 |

1,478 |

27.4 |

1,637 |

30.4 |

|

Good behaviour bond*** |

416 |

8.5 |

569 |

10.5 |

550 |

10.2 |

|

Detention |

487 |

9.9 |

541 |

10.0 |

529 |

9.8 |

|

Fine |

656 |

13.3 |

572 |

10.6 |

523 |

9.7 |

|

Other |

411 |

8.4 |

504 |

9.3 |

444 |

8.2 |

|

Total cases finalised |

4,921 |

100.0 |

5,399 |

100.0 |

5,392 |

100.0 |

Source: Department of Justice, Report on Criminal Cases in the Children's Court of Western Australia 2013/14 to 2017/18

* Community orders includes Intensive Supervision Orders, Intensive Youth Supervision Orders, Community Based Orders and Youth Community Based Orders and they usually have a community work component as well as a supervision component.

** No punishment orders are generally only used for first time offenders or where the court is satisfied that the offender has been punished by some other means.

*** A Good Behaviour Bond is generally given to young people who have committed minor offences or where victim involvement is minimal. The young person's ability to pay must also be considered because a monetary bond is set and will be forfeited if the young person reoffends.

Sentences imposed on finalised criminal cases in the Children’s Court, number, WA, 2015–16 to 2017–18

Source: Department of Justice, Report on Criminal Cases in the Children's Court of Western Australia 2013/14 to 2017/18

There has been a reduction in fines imposed from 2015–16 to 2017–18 (13.3% of sentences compared to 9.7% of sentences). There has been little change to the proportion of detention sentences imposed since 2015–16.

Endnotes

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Youth Justice in Australia 2017–18, Cat No JUV 129, AIHW, p. 1.

- Australia and New Zealand's Children's Commissioner and Guardians Group (ANZCCG), ANZCCG Communique - Meeting 11 and 12 November 2019, ANZCCG.

- Sentencing Advisory Council 2016, Reoffending by Children and Young People in Victoria, Victorian Government, p. 26.

- A proceeding is a legal action initiated against an alleged offender for an offence(s). Legal actions can be court actions (laying charges) or non-court actions (diversions, infringements, warnings). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, Recorded Crime – Offenders, Australia, 2018-19

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, 3101.0 Australian Demographic Statistics, Sep 2019 - TABLE 55. Estimated Resident Population By Single Year Of Age, Western Australia, ABS.

- WA Auditor General 2008, Performance examination – The Juvenile Justice System: Dealing with young people under the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 17.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, 4519.0 - Recorded Crime - Offenders, 2018-19: Table 21 Youth Offenders, Sex and principal offence by age, 2018–19, selected states and territories, ABS.

- All Australian states and territories have 10 years of age as the age of criminal responsibility.

- WA Government, Young Offenders Act 1994, S. 23.

- WA Auditor General 2017, Diverting Young People Away from Court, Report 18: November 2017, WA Government, p. 5.

- Ibid, p. 6.

- Ibid, p. 6.

Last updated June 2020

This measure looks at the number of children and young people under the supervision of the Department of Justice – Corrective Services division. Children and young people under youth justice supervision have been charged with an offence and may be unsentenced or sentenced. Unsentenced children and young people may have been charged but are awaiting a court date or a sentence, or may have been found guilty (or pleaded guilty) and are awaiting sentencing.

Children and young people may be supervised in the community or detained in Banksia Hill Detention Centre (Banksia Hill), which is the sole facility for the detention of children and young people aged 10 to 17 years in WA.

Children and young people who are under youth justice supervision have generally experienced significant challenges and disadvantage in their lives which can include poverty, high risk of drug and alcohol issues, mental health issues, involvement with the child protection system and episodes of homelessness.1,2,3 Evidence also suggests that many children and young people in the youth justice system may have cognitive disabilities which are undiagnosed.4 These children and young people can therefore have highly complex support needs.

The majority (81.4% in 2018–19) of children and young people under youth justice supervision are supervised in the community rather than in detention.

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Community |

608 |

82.5 |

596 |

81.4 |

594 |

80.3 |

590 |

81.4 |

|

Detention |

131 |

17.8 |

138 |

18.9 |

147 |

19.9 |

133 |

18.3 |

|

Total |

737 |

100.0 |

732 |

100.0 |

740 |

100.0 |

725 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Tables S10a, S45a and S83a

Notes:

1. The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

2. The ‘average day’ measure is calculated by summing the number of days each young person spends under supervision during the financial year, and dividing this by the total number of days in the year. It reflects the number under supervision on any given day during the year, and indicates the average number of young people supported by the supervision system at any time. This summary measure reflects both the number of young people supervised, and the amount of time they spent under supervision.

From 2015–16 to 2018–19, the number of children and young people under youth justice supervision on an average day in WA decreased marginally from 737 to 725 children and young people. Over this period the number of children and young people under community-based supervision on an average day decreased from 608 to 590 and there was a marginal increase in the number of children and young people in detention on an average day (from 131 to 133).

Female children and young people are less likely to be under supervision than their male peers. In 2018–19 in WA, female children and young people aged 10 to 17 represented 19.7 per cent of the population under community-based supervision and 10.5 per cent of the population in detention.

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Community |

474 |

80.3 |

116 |

19.7 |

590 |

100.0 |

|

Detention |

120 |

90.2 |

14 |

10.5 |

133 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

595 |

82.1 |

129 |

17.8 |

725 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Tables S134a), b) and c)

Note: The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

Notwithstanding that the absolute numbers are comparatively small, the number of female children and young people in detention on an average day almost doubled from 8 in 2017–18 to 14 in 2018–19.

|

Male |

Female |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Total |

|

|

2015–16 |

123 |

93.9 |

8 |

6.1 |

131 |

|

2016–17 |

130 |

94.2 |

8 |

5.8 |

138 |

|

2017–18 |

139 |

94.6 |

8 |

5.4 |

147 |

|

2018–19 |

120 |

90.2 |

14 |

10.5 |

133 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S134c)

In 2018–19 in WA, Aboriginal children and young people were 18 times more likely to be under community-based supervision and 45 times more likely to be in detention on an average day compared to non-Aboriginal children and young people.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|||||

|

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

Rate Ratio Aboriginal/ |

|

|

Community |

338 |

193.4 |

252 |

10.6 |

590 |

23.1 |

18.2 |

|

Detention |

102 |

58.7 |

31 |

1.3 |

133 |

5.2 |

45.2 |

|

Total |

441 |

252.5 |

284 |

12.0 |

725 |

28.4 |

21.1 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, various tables

Notes:

1. The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

2. Rate is number of young people per 10,000 of relevant population.

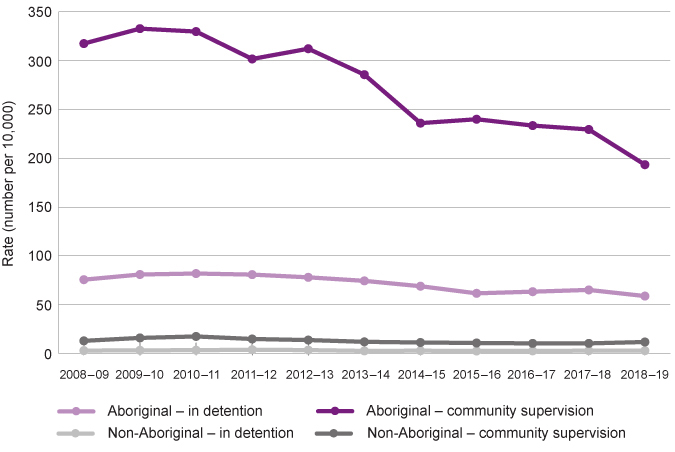

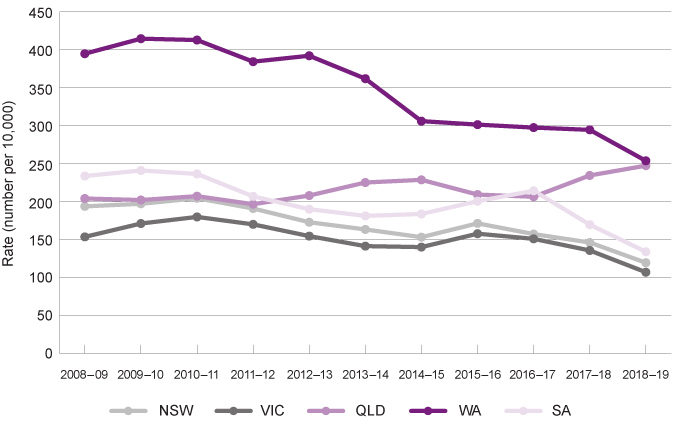

The rate of children and young people under supervision in WA has been decreasing since 2008–09 (37.9 per 10,000 in 2008–09 compared to 28.4 per 10,000 in 2018–19).

In particular, the rate of Aboriginal children and young people under supervision has fallen substantially from 393.7 per 10,000 children and young people in 2008–09 to 252.5 children and young people in 2018–19. This includes a significant decrease in the past year (from 293.3 per 10,000 children and young people under supervision in 2017–18).

Furthermore, the rate of Aboriginal children and young people in detention shows a sustained downward trend (from 75.5 in 2008–09 to 58.7 in 2018–19).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

||||||

|

Detention |

Community |

All |

Detention |

Community |

All |

Total |

|

|

2008–09 |

75.5 |

317.6 |

393.7 |

1.8 |

11.8 |

13.6 |

37.9 |

|

2009–10 |

80.8 |

332.9 |

413.5 |

2.1 |

14.8 |

16.9 |

42.6 |

|

2010–11 |

81.8 |

329.9 |

411.7 |

2.2 |

16.3 |

18.4 |

44.2 |

|

2011–12 |

80.7 |

301.8 |

383.2 |

2.7 |

13.7 |

16.5 |

40.6 |

|

2012–13 |

77.9 |

312.3 |

391.0 |

2.3 |

12.6 |

15.0 |

39.7 |

|

2013–14 |

74.3 |

285.7 |

360.8 |

1.5 |

10.8 |

12.2 |

35.1 |

|

2014–15 |

68.8 |

236.0 |

304.8 |

1.7 |

10.1 |

11.8 |

31.1 |

|

2015–16 |

61.5 |

240.0 |

300.2 |

1.4 |

9.6 |

10.9 |

30.1 |

|

2016–17 |

63.2 |

233.5 |

296.3 |

1.5 |

9.2 |

10.7 |

29.6 |

|

2017–18 |

65.0 |

229.5 |

293.3 |

1.7 |

9.2 |

11.0 |

29.5 |

|

2018–19 |

58.7 |

193.4 |

252.5 |

1.7 |

10.6 |

12.0 |

28.4 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Tables S12a, S47a and S85a

Notes:

1. The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

2. Rates are number of children and young people per 10,000 of relevant population.

Children and young people aged 10 to 17 years under supervision on an average day by Aboriginal status and supervision type, rate, WA, 2008–09 to 2018–19

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Tables S12a, S47a and S85a

While the overall reduction is a positive development, WA continues to have the highest rate of Aboriginal children and young people under supervision across all jurisdictions in Australia.

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

|

|

2008-09 |

193.7 |

153.5 |

202.8 |

393.7 |

233.7 |

120.1 |

219.5 |

n/a |

|

2009–10 |

197.1 |

171.1 |

200.8 |

413.5 |

241.0 |

137.9 |

212.0 |

n/a |

|

2010–11 |

204.4 |

179.8 |

205.9 |

411.7 |

236.5 |

112.9 |

296.7 |

n/a |

|

2011–12 |

190.9 |

170.0 |

195.3 |

383.2 |

206.9 |

65.1 |

334.2 |

n/a |

|

2012–13 |

172.8 |

154.5 |

206.7 |

391.0 |

190.0 |

56.4 |

244.0 |

89.5 |

|

2013–14 |

163.3 |

141.3 |

223.9 |

360.8 |

181.2 |

37.2 |

220.0 |

140.6 |

|

2014–15 |

153.1 |

140.0 |

227.4 |

304.8 |

183.7 |

35.8 |

243.2 |

118.7 |

|

2015–16 |

171.1 |

157.7 |

208.0 |

300.2 |

200.5 |

56.7 |

185.2 |

128.0 |

|

2016–17 |

157.2 |

150.9 |

205.1 |

296.3 |

214.3 |

59.4 |

158.2 |

128.3 |

|

2017–18 |

146.1 |

135.6 |

233.2 |

293.3 |

169.6 |

66.0 |

235.0 |

120.9 |

|

2018–19 |

119.4 |

106.9 |

246.1 |

252.5 |

133.9 |

74.3 |

129.7 |

133.5 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S12a: Young people aged 10–17 under supervision on an average day by Indigenous status, states and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19 (rate)

Notes:

1. Rate is the number of young people per 10,000 of relevant population.

2. The Northern Territory did not supply data for 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11 and 2011–12.

Aboriginal children and young people aged 10 to 17 years under supervision on an average day by selected jurisdictions, rate, Australia, 2008–09 to 2018–19

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S12a: Young people aged 10–17 under supervision on an average day by Indigenous status, states and territories, 2008–09 to 2018–19 (rate)

Note: Tasmania and the ACT have been excluded from the graph as they are smaller populations. The NT has been excluded due to missing data before 2012–13.

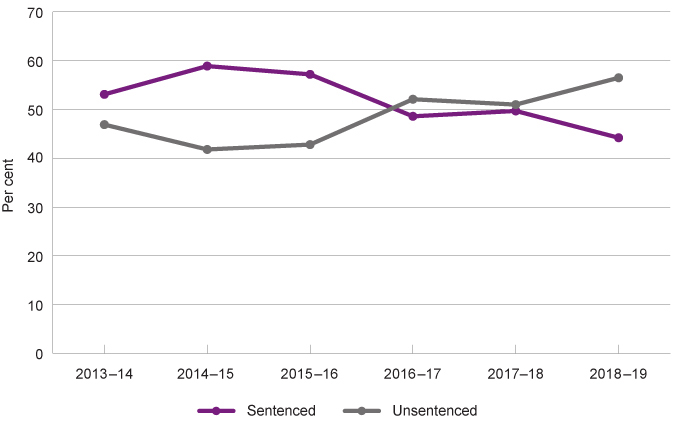

Most (93.6%) children and young people supervised in the community have been sentenced. In contrast, more than one-half (58.6%) of children and young people in detention on an average day in 2018–19 were unsentenced.

|

Community |

Detention |

|||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Sentenced |

552 |

93.6 |

56 |

42.1 |

|

Unsentenced |

55 |

9.3 |

78 |

58.6 |

|

Total |

590 |

100.0 |

133 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Tables S67a) and S110a)

Note: The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

Unsentenced children and young people who are supervised in the community include those who have been granted bail and have suitable accommodation and a responsible adult to take responsibility for them. Children and young people who are unsentenced in detention can fall into several categories:

- have been arrested and are waiting for a first court appearance or bail determination

- have been granted bail but are remanded in custody due to a lack of suitable accommodation and/or a responsible adult

- have been denied bail and are waiting for their court case

- are waiting to be sentenced after conviction.

Since 2014–15, the number of children and young people who are unsentenced in Banksia Hill has increased and recently surpassed the number of children and young people who are sentenced.

The overall decrease from 153 children and young people in detention on an average day in 2017–18 to 138 in 2018–19 was entirely due to a decrease in the number of sentenced children and young people in detention (from 76 to 61 – a decrease of 19.7%). The numbers remain unchanged for those children and young people who are unsentenced.

|

Sentenced |

Unsentenced |

Total |

|||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

|

|

2013–14 |

85 |

53.1 |

75 |

46.9 |

160 |

|

2014–15 |

93 |

58.9 |

66 |

41.8 |

158 |

|

2015–16 |

79 |

57.2 |

59 |

42.8 |

138 |

|

2016–17 |

71 |

48.6 |

76 |

52.1 |

146 |

|

2017–18 |

76 |

49.7 |

78 |

51.0 |

153 |

|

2018–19 |

61 |

44.2 |

78 |

56.5 |

138 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, S113: Young people in detention on an average day(a) by legal status and Indigenous status, states and territories, 2013–14 to 2018–19

* This data includes young people aged 18+ years on an average day, the majority of whom were sentenced.

Note: The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

Children and young people aged over 10 years* in detention on an average day by legal status, per cent, WA, 2013–14 to 2018–19

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S113: Young people in detention on an average day(a) by legal status and Indigenous status, states and territories, 2013–14 to 2018–19

On an average day in 2018–19, 14 children and young people aged 10 to 13 years were unsentenced in Banksia Hill. Of these, 11 (78.6%) were Aboriginal children and young people.

|

10 to 13 years |

14 to 17 years |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Aboriginal |

11 |

78.6 |

46 |

73.0 |

58 |

74.4 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

3 |

21.4 |

17 |

27.0 |

20 |

25.6 |

|

Total |

14 |

100.0 |

63 |

100.0 |

78 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S114a: Young people in unsentenced detention on an average day(a) by age and Indigenous status, states and territories, 2018–19

Note: The number of children and young people on an average day may not sum due to rounding.

During the year a total of 143 children aged 10 to 13 years were in Banksia Hill while unsentenced. Two-thirds (66.4%) of these children and young people were Aboriginal, which is greater than the proportion of Aboriginal children and young people aged 14 to 17 years in unsentenced detention (58.6%).

|

10 to 13 years |

14 to 17 years |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Aboriginal |

95 |

66.4 |

363 |

58.6 |

460 |

60.1 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

48 |

33.6 |

256 |

41.4 |

305 |

39.9 |

|

Total |

143 |

100.0 |

619 |

100.0 |

765 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S114b: Young people in unsentenced detention during the year by age and Indigenous status, states and territories, 2018–19

Note: Age is calculated as at start of financial year if first period of unsentenced detention in the relevant year began before the start of the financial year, otherwise age calculated as at start of first period of unsentenced detention in the relevant year.

Notably, the large majority of children and young people under 14 years of age are not ultimately sentenced to detention.5 While 143 children and young people aged 10 to 13 years spent time in unsentenced detention during 2018–19, only 13 children and young people aged between 10 and 13 years were in sentenced detention during the year.6

The average length of time children and young people spent in unsentenced detention in 2018–19 was 38 days.7 Aboriginal children and young people spent an average of 46 days in unsentenced detention and non-Aboriginal children and young people spent an average of 25 days.8

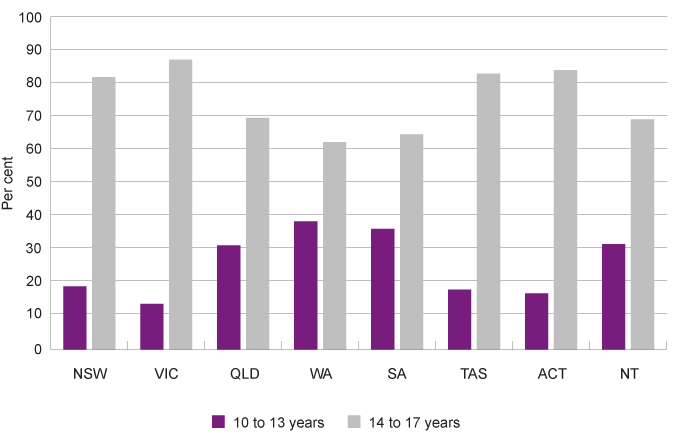

Of all Australian jurisdictions, in 2018–19 WA had the highest proportion of children and young people under supervision who entered supervision for the first time when they were aged 10 to 13 years (38.2%).

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

Aust |

|

|

10 to 13 years |

18.8 |

13.6 |

31.0 |

38.2 |

35.9 |

17.8 |

16.7 |

31.4 |

26.1 |

|

14 to 17 years |

81.2 |

86.4 |

69.0 |

61.8 |

64.1 |

82.2 |

83.3 |

68.6 |

73.9 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S19: Young people under supervision during the year by Indigenous status and age at first supervision, states and territories, 2018–19

Children and young people under supervision during the year by age at first supervision and jurisdiction, per cent, Australia, 2018–19

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S19: Young people under supervision during the year by Indigenous status and age at first supervision, states and territories, 2018–19

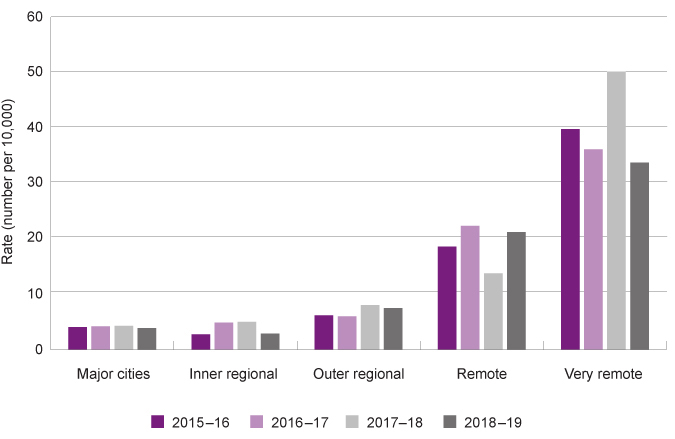

On an average day in 2018–19, children and young people aged 10 to 17 years who were from very remote areas of WA were nine times as likely to be in detention (sentenced and unsentenced) as those from Perth (33.4 per 10,000 compared with 3.8 per 10,000).

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

Major cities |

4.0 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

|

Inner regional |

2.7 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

2.8 |

|

Outer regional |

6.1 |

5.9 |

7.9 |

7.4 |

|

Remote |

18.4 |

22.1 |

13.6 |

21.0 |

|

Very remote |

39.4 |

35.8 |

49.7 |

33.4 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19 and previous years, Table S99c: Young people aged 10–17 in detention on an average day by remoteness of usual residence, states and territories (rate)

Note:

1. This includes both sentenced and unsentenced detention.

2. Rate is the number of young people per 10,000 of relevant population.

Children and young people aged 10 to 17 years in detention on an average day by remoteness of usual residence, rate, WA, 2018–19

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S19: Young people under supervision during the year by Indigenous status and age at first supervision, states and territories, 2018–19

In 2018–19, there was a decrease in the rate of detention for children and young people from very remote areas from 49.7 per 10,000 in 2017–18 to 33.4 per 10,000 in 2018-19.

Children living in remote and very remote areas in WA have a high risk of social exclusion and disadvantage9 and are more likely to be living in communities where there are higher levels of unemployment, families experiencing poverty or financial stress, poor housing conditions and a lack of access to services.10

Many children and young people under youth justice supervision have also been involved in the child protection system either as the subject of investigations, being under care and protection orders or in out-of-home care. For more information refer to the Young people in care section.

Self-harm or suicide while in detention

In 2018, there were 172 recorded incidents of self-harm by children and young people in Banksia Hill Detention Centre. This represents a slight reduction in recorded incidents of self-harm and attempted suicide from recent years, however, they were still significantly higher than prior to 2016.

The significant increase in self-harm and attempted suicide incidents in 2016 and 2017 coincided with a number of serious incidents at the facility including assaults and damage of property. This resulted in increased lockdowns and less access to education, recreation, and other services.11

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018* |

|

|

Self-harm |

74 |

71 |

37 |

77 |

191 |

184 |

172 |

|

Attempted suicide |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

Source: Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2018, 2017 Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre and Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Legislative Council, 3 September 2019

* Response of the Honourable Stephen Dawson to questions on incidents of self-harm and attempted suicides from the Honourable Alison Xamon, Parliament of WA, Legislative Council, 3 September 2019.

There is no information on the number of children and young people involved in the above incidents.

In the six months from January to June 2019, there was also one attempted suicide at Banksia Hill.12

There is no further breakdown by age, Aboriginal status or gender of the children and young people self-harming or attempting suicide in the centre.

Incidents of self-harm or attempted suicide while children and young people are in custody (detention) are reported in the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services: Youth Justice. While all other jurisdictions report on this measure, data is not publicly reported for WA.13

Cost of youth justice services

The cost of detaining children and young people in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre ($54.5 million in 2018–19) far outweighs the cost of community-based supervision ($21.1 million) and diversion through the Juvenile Justice Teams (group conferencing) ($21.1 million).

The total expenditure on youth justice services in WA has declined over the past five years (from $115.7 million in 2014–15 to $96.7 million in 2018–19). The decrease was largely due to a significant reduction in expenditure on group conferencing (eg Juvenile Justice Teams).

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

||

|

Detention-based |

$'000 |

55,214 |

54,475 |

57,766 |

56,106 |

54,479 |

|

$/child |

226.6 |

222.6 |

233.5 |

223.6 |

213.7 |

|

|

Community-based |

$'000 |

25,316 |

25,408 |

26,114 |

23,725 |

21,094 |

|

$/child |

103.9 |

103.8 |

105.6 |

94.6 |

82.7 |

|

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020 - Youth Justice, Table 17A.8 State and Territory government real expenditure on youth justice services, (2018–19 dollars)

* Group conferencing in WA is principally implemented through Juvenile Justice Teams where the young person and their families (and sometimes the victims) develop an action plan for the young person. If he or she does the right thing and follows the plan, they do not get a criminal record.

Real government expenditure on youth justice services by service type, $’000 and $/child, WA, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020 - Youth Justice, Table 17A.8 State and Territory government real expenditure on youth justice services, (2018–19 dollars)

A low expenditure level or low cost/child can reflect more efficient service provision, however, it can also mean less investment in rehabilitation programs or less intensive case management of children and young people in the youth justice system.

More information is required to evaluate the decrease in both total expenditure and expenditure per child and its impact on the wellbeing outcomes for children and young people in the WA youth justice system.

Endnotes

- Baldry E et al 2018, ‘Cruel and unusual punishment’: an inter-jurisdictional study of the criminalisation of young people with complex support needs, Journal of Youth Studies, Vol 21, No 5.

- WA Auditor General 2008, Performance examination – The Juvenile Justice System: Dealing with young people under the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 25.

- Meurk C et al 2020, Direction: mental health needs of justice-involved young people in Australia, Kirby Institute, UNSW.

- Bower C et al 2018, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8.

- Refer to Department of Corrective Services 2016, Young People in the Youth Justice System: A Review of the Young Offenders Act 1994, WA Government, p. 10.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Cat No JUV 132, AIHW, Table S121b: Young people in sentenced detention during the year by age and Indigenous status, states and territories, 2018–19.

- Time spent includes all the time spent under supervision during 2018–19 including multiple periods of supervision and periods that were not yet completed at 30 June 2018.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Cat No JUV 132, AIHW, Table S118: Average length of time young people spent in unsentenced detention during the year by Indigenous status, states and territories , 2014–15 to 2018–19 (days).

- Miranti R et al. 2018, Child Social Exclusion, Poverty And Disadvantage In Australia, NATSEM, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA), University of Canberra.

- American Psychological Association 2019, Fact sheet: violence and socioeconomic status, American Psychological Association.

- Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2018, 2017 Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre, WA Government, p. iv.

- Response of the Honorable Stephen Dawson to questions on incidents of self-harm and attempted suicides from the Honorable Alison Xamon, Parliament of WA, Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Legislative Council, 3 September 2019

- The Productivity Commission reports notes that in WA, data systems do not distinguish between incidents of self-harm/attempted suicide and the level of treatment required e.g. hospitalisation or non-hospitalisation.

Last updated June 2020

The majority of young people who are currently under youth justice supervision in WA have previously been involved in the youth justice system. However, more than one-third (36.5%) of children and young people under supervision in WA in 2018–19 were new to supervision in that year.1

Returns to sentenced youth justice supervision2 is defined as the proportion of young people released from sentenced supervision who are aged 10 to 16 years at time of release who returned to sentenced supervision within 12 months.3 This measure does not include young people aged 17 years leaving sentenced supervision as if they are sentenced again it will most likely be within the adult system.

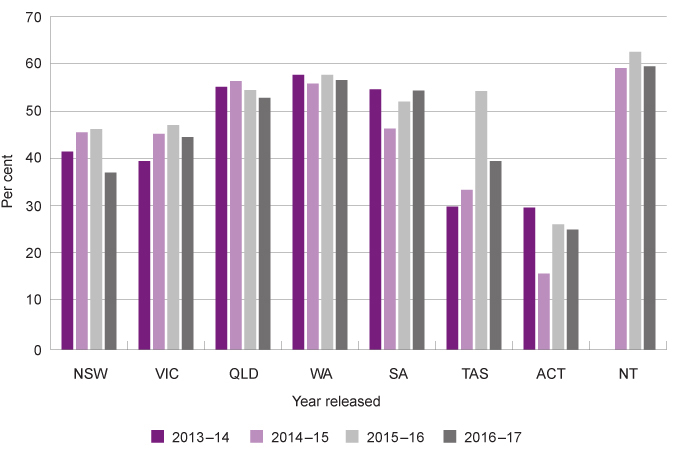

WA has the second highest rate of return to sentenced supervision of all jurisdictions in Australia. In 2016–17, 365 (56.2%) children and young people released from sentenced supervision in WA returned within 12 months.

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

Australia |

|

|

2013–14 |

41.3 |

39.3 |

54.8 |

57.3 |

54.3 |

29.8 |

29.6 |

n/a |

49.6 |

|

2014–15 |

45.3 |

45.0 |

56.0 |

55.5 |

46.1 |

33.3 |

15.8 |

58.7 |

51.5 |

|

2015–16 |

46.0 |

46.8 |

54.1 |

57.3 |

51.7 |

53.9 |

26.1 |

62.1 |

52.1 |

|

2016–17 |

36.9 |

44.3 |

52.5 |

56.2 |

54.0 |

39.3 |

25.0 |

59.1 |

48.9 |

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020 - Youth Justice, Table 17A.26

Note: Sentenced supervision includes supervision in the community.

Children and young people aged 10 to 16 years released from sentenced supervision who returned to sentenced supervision within 12 months by year of release and jurisdiction, per cent, Australia, 2013–14 to 2016–17

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020 - Youth Justice, Table 17A.26

The WA Department of Justice reports on the rate at which young people return to sentenced detention (in the youth justice system) within two years of their release from sentenced detention. This analysis does not exclude young people aged 16 or 17 years and therefore does not account for young people who may have entered the adult criminal justice system.

|

Number released |

Number returned |

Rate of return |

|

|

2015–16 |

227 |

124 |

54.6 |

|

2016–17 |

200 |

110 |

55.0 |

|

2017–18 |

189 |

111 |

58.7 |

|

2018–19* |

174 |

92 |

52.9 |

Source: Department of Justice, Annual Report 2018–19

* The number released and number returned in 2018–19 was provided on request by the Department of Justice to the Commissioner for Children and Young People.

Note: This indicator is calculated by dividing the number of young people who return to detention under sentence within two years of their release from detention, by the number of sentenced young people released from detention during the exit year, with the result expressed as a percentage. The calculation does not include returns to adult prisons, therefore someone may be 16 or 17 years-old at the time of release, re-offend when they are 18 and are sentenced as an adult prisoner, and would not be counted as a return.

There has been a slight reduction in the rate of return to sentenced detention over the past four years (from 54.6% in 2015–16 to 52.9% in 2017–18).

There is no recent data available on the number or proportion of young people who have been in the youth justice system and later enter the adult criminal justice system. Administrative data is not collected to track whether children and young people in the youth justice system enter the adult criminal justice system once they turn 18 years of age.4

Endnotes

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Youth Justice in Australia 2018–19, Table S16: Young people under supervision during the year by first supervision, states and territories, 2013–14 to 2018–19.

- This measure should not be interpreted as a measure of recidivism. Accurately measuring recidivism would require information on all criminal acts committed by a young person which would include those not coming to the attention of authorities, and for those that did not result in a return to youth justice sentenced supervision. Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services – Youth Justice, Australian Government.

- Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services – Youth Justice, Australian Government.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2014, Pathways through youth justice supervision, Juvenile justice series no 15, Cat no JUV 40, AIHW, p. 20-21.

Last updated June 2020

At 30 June 2019, there were 2,420 WA young people in care aged between 10 and 17 years, more than one-half of whom (53.3%) were Aboriginal.1

The vast majority of children and young people who have experienced abuse and maltreatment do not go on to commit criminal offences, however, research shows that children and young people who have been abused or maltreated are at greater risk of engaging in violent and antisocial behaviour.2 Longitudinal studies generally show that a combination of individual and social risk factors along with experiences of abuse and neglect can lead to offending behaviour.3

Using data from the linked child protection and youth justice supervision data collections AIHW reported on young people aged 10 to 17 years who had received child protection services and were under youth justice supervision at any time between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2018.

Across Australia children and young people who had received child protection services were nine times as likely as the general population to have also been under youth justice supervision.4

Almost 10 per cent (9.3%) of children and young people in WA involved in the child protection system had also been under youth justice supervision between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2018.

|

Number receiving child protection services |

Number also with youth justice supervision |

Per cent also with youth |

||

|

Male |

Aboriginal |

1,176 |

342 |

29.1 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

2,114 |

214 |

10.1 |

|

|

Total |

3,590 |

556 |

15.5 |

|

|

Female |

Aboriginal |

1,543 |

137 |

8.9 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

2,665 |

94 |

3.5 |

|

|

Total |

4,723 |

231 |

4.9 |

|

|

All |

Aboriginal |

2,738 |

479 |

17.5 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

4,873 |

308 |

6.3 |

|

|

Total |

8,493 |

787 |

9.3 |

|

Source: AIHW, Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision: 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2018, Table S3a, b and c: Young people aged 10–17 who had received child protection services and who had also been under youth justice supervision

Note: These data include only those young people who were aged 10 to 14 years at 1 July 2014. This is to ensure young people in the study were aged between 10 and 17 and therefore eligible for both services for the entire measurement period.

A greater proportion (17.5%) of Aboriginal children and young people in care in WA had also been under youth justice supervision than non-Aboriginal children and young people in care (6.3%). Furthermore, a greater proportion (15.5%) of male children and young people in care had also been under youth justice supervision than female children and young people in care (4.9%).

There is evidence to suggest that children and young people who are in out-of-home care, particularly living in residential care, are more likely to have challenging behaviour criminalised through calls to the police. For example, where police are called to deal with a young person who has broken something in the home or stayed out past their curfew.5,6

For further information on how children and young people in care can be unnecessarily exposed to contact with police and the youth justice system, refer to the Queensland Family and Child Commission 2018 report: The criminalisation of children living in out-of-home care in Queensland.

The AIHW also found that young people in the youth justice systems around Australia were nine times more likely to have received child protection services than the general population.7

In WA, 38.9 per cent of children and young people under youth justice supervision had also been involved in the child protection system.8

|

Number under youth justice supervision |

Number also received child protection services |

Per cent also received child protection services |

||

|

Male |

Aboriginal |

857 |

341 |

39.8 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

736 |

217 |

29.5 |

|

|

Total |

1,594 |

558 |

35.0 |

|

|

Female |

Aboriginal |

244 |

137 |

56.2 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

193 |

95 |

49.2 |

|

|

Total |

437 |

232 |

53.1 |

|

|

All |

Aboriginal |

1,101 |

478 |

43.4 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

929 |

312 |

33.6 |

|

|

Total |

2,031 |

790 |

38.9 |

|

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision: 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2018, Table S4a, b and c: Young people aged 10–17 who had been under youth justice supervision and who had also received child protection services

Note: These data include only those young people who were aged 10 to 14 years at 1 July 2014. This is to ensure young people in the study were aged between 10 and 17 years and therefore eligible for both services for the entire measurement period.

A greater proportion of female children and young people in the youth justice system than male children and young people have also received child protection services (53.1% of female children and young people compared to 35.0% of male children and young people).

Data on how many children and young people in care in WA have contact with the WA Police Force is not publicly available.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018-19, WA Government p. 26.

- Malvaso C 2017, Investigating the complex links between maltreatment and youth offending, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Ibid.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision: 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2018, AIHW, p. iv.

- Victorian Legal Aid 2016, Care not custody, A new approach to keep kids in residential care out of the criminal justice system, Victorian Legal Aid.

- CREATE Foundation 2018, Youth Justice Report: Consultation with young people in out-of-home care about their experiences with police, courts and detention, CREATE Foundation, p. 32-33.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision: 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2018, AIHW, p. 19.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Young people in child protection and under youth justice supervision: 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2018, AIHW.

Last updated June 2020

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018 data collection reports that approximately 30,200 WA children and young people (9.2%) aged five to 14 years have reported disability.1,2

People with disability are more likely than the general population to be victims of crime, rather than perpetrators. The current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability has already highlighted multiple instances within institutional settings where children and young people with disability have been victims of abuse, neglect and violence.3

However, some types of disability increase the likelihood of children and young people coming into contact with the justice system as perpetrators. In particular, cognitive disabilities and mental health disorders (and the combination thereof) increase the risk of behavioural issues which can lead to violent and antisocial behaviour.4

Research shows that children and young people in the youth justice system are more likely to have cognitive impairment and mental health disorders.5,6 Yet, there are limited health assessment or diagnostic processes for children and young people entering the juvenile justice system or having contact with police.7,8 Furthermore, there is no administrative data that monitors the prevalence of disability for children and young people in the youth justice system in WA or nationally.9

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a particular concern for children and young people in the youth justice system in WA. FASD is characterised by impairment in executive function, memory, language, learning and attention, due to prenatal alcohol exposure, and can result in a range of difficulties for young people including understanding consequences, learning from past experiences, decision making and general impulsivity.10 Young people with FASD are therefore much more susceptible to repeat involvement with the justice system.

International research suggests that 60.0 per cent of people with FASD have been arrested, charged or convicted of a criminal offence and young people affected by FASD are over-represented in the youth justice system.11

In 2017, a Telethon Kids Institute research team found that 89.0 per cent of young people in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre had at least one form of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, while 36.0 per cent (36 young people) were found to have FASD.12 It is of significant concern that only two of the young people with FASD had been diagnosed prior to participation in the study.13 Since that report, there has been additional training in FASD for staff at Banksia Hill.14

Regarding mental health, the NSW government’s 2015 survey on the health of young people in the NSW justice system found that most participants (83.3%) met the threshold criteria for at least one psychological disorder, and 63.0 per cent for two or more.15