Mental health

It is increasingly recognised that the basis for good mental health is built early in life, as children’s relationships with parents, caregivers and other adults and children influence the developing brain.1 Evidence shows that mental health problems can and do occur in young children,2 yet, the focus of mental health services for children is generally on adolescents.

This indicator plans to report on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA children aged 0 to 5 years, however, there is limited data currently available.

Last updated February 2022

Limited data is available on whether WA children aged 0 to 5 years are mentally healthy.

Overview

There remains a reluctance to acknowledge that very young children can and do experience mental health issues that may result in serious social, emotional or behavioural problems in adolescence and adulthood (for example, aggression, anxiety and depression). Good mental health for infants and young children is about developing the capacity to experience, express and regulate emotions, to form close and secure relationships and to explore their environment and learn.1

Reliable data that provides information about the mental health and wellbeing of WA children aged 0 to five years and the extent of mental health problems among them is not readily available.

Limited recent data exists on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA children aged 0 to five years.

In the Perth metropolitan area 88.6 per cent of children assessed through the Ages and Stages®: Social Emotional Questionnaires (ASQ:SE2) at age two years in 2020 were determined to be ‘on track’.

Areas of concern

Limited data is available on the mental health of children aged 0 to five years.

The proportion of eligible children with a completed ASQ:SE2 in 2020 by age group was 52.9 per cent at the four-month check, 35.5 per cent at the 12-month check and 19.5 per cent at the two-year check.

A higher number of two year-old WA Aboriginal children were recommended for referral under the ASQ:SE2 than non-Aboriginal children (14.8% compared to 6.9%) and a higher number of male children were recommended for referral than female children (9.4% compared to 4.5%).

Endnotes

- Osofsky J and Thomas K 2012, What is Infant Mental Health?, Zero to Three, Vol 33, No. 2.

Last updated February 2022

Significant mental health problems can and do occur in young children.1 Mental health issues in young children occur as a result of the interaction between a child’s genetic pre-disposition (e.g. temperament, other health issues such as intellectual disability, ADHD etc.), their exposure to adverse experiences or environments and their access to secure and nurturing relationships.2

Mental health issues amongst younger children often exhibit as social, behavioural or emotional difficulties.

Good mental health provides an essential foundation for children’s healthy development. Mental health issues impact children’s ability to form healthy relationships, participate in learning and cope with adversity.3 In some instances mental illness can ultimately lead to psychosocial disability where a person is unable to participate fully in life due to mental ill-health.4

However, identification and diagnosis of mental health issues in very young children is difficult. This is in part due to a lack of knowledge and skills that would help health professionals identify mental health issues in young children, combined with the often transient nature of social-emotional problems during the early years.5 This impacts the ability to accurately estimate the prevalence of mental health issues for children aged 0 to five years.

There is limited data on the prevalence of mental health issues for Australian or WA children aged 0 to 5 years.

There are a number of tools for measuring mental health in young children. These include diagnostic tools (e.g. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Young Children (DISC-YC))6 and screening tools (e.g. Ages and Stages Questionnaires®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2)).7

In 2013 and 2014 the University of WA and the Telethon Kids Institute conducted the second national Young Minds Matter survey. This survey collected data from over 6,300 Australian families with children and young people aged four to 17 years. There is unfortunately no ability to disaggregate the data by jurisdiction. The survey is also not currently planned to be repeated.8

This survey assessed mental disorders using specific diagnostic modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV). Under DISC-IV, disorder status is determined according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental Disorders Version IV (DSM-IV).9 DISC-IV (and the more recent DISC-V) are not suitable for children under four years of age.10

This survey estimated that in the 12 months prior to the survey, 13.6 per cent of children aged four to 11 years experienced a mental disorder.11 Among children aged four to 11 years, ADHD (8.2%) and anxiety disorders (6.9%) were the most common.12

There were, however, differences between male and female children. Male children aged four to 11 years were more likely to experience ADHD (10.9% compared to 5.4%) and anxiety disorders (7.6% to 6.1%). It should be noted that research suggests that female children are under‑diagnosed for ADHD in childhood, as the symptoms are less overt and often co-exist with different disorders from male children.13

The Young Minds Matter survey also found that children in low-income families, with parents and carers with lower levels of education or with higher levels of unemployment, had higher rates of mental disorders. There was also a higher rate of mental disorders in non-metropolitan areas.14

The Young Minds Matter survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders for Aboriginal children and young people due to the random sampling methodology and cultural issues that could not be addressed sufficiently in a national survey.15

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE2) is a screening and monitoring system designed to identify possible social and emotional difficulties in infants and young children. While this is not a diagnostic tool, it can indicate whether a child is at risk of mental health issues.16

In WA, the ASQ:SE2 is generally offered to parents by their health professionals at the four-month, 12-month and two-year child health checks.17 It measures seven areas of social emotional behaviour including self-regulation, compliance, communication, adaptive functioning, autonomy, affect, and interaction with people.18

Not all eligible children are assessed using the ASQ-SE2. The proportion of eligible children with a completed ASQ:SE2 in 2020 by age group was 52.9 per cent at the four-month check, 35.5 per cent at the 12-month check and 19.5 per cent at the two-year check. The overall ASQ results and completion rates are discussed in the Developmental screening indicator.

The proportion of eligible children with a completed ASQ-SE2 decreases significantly with age for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children.

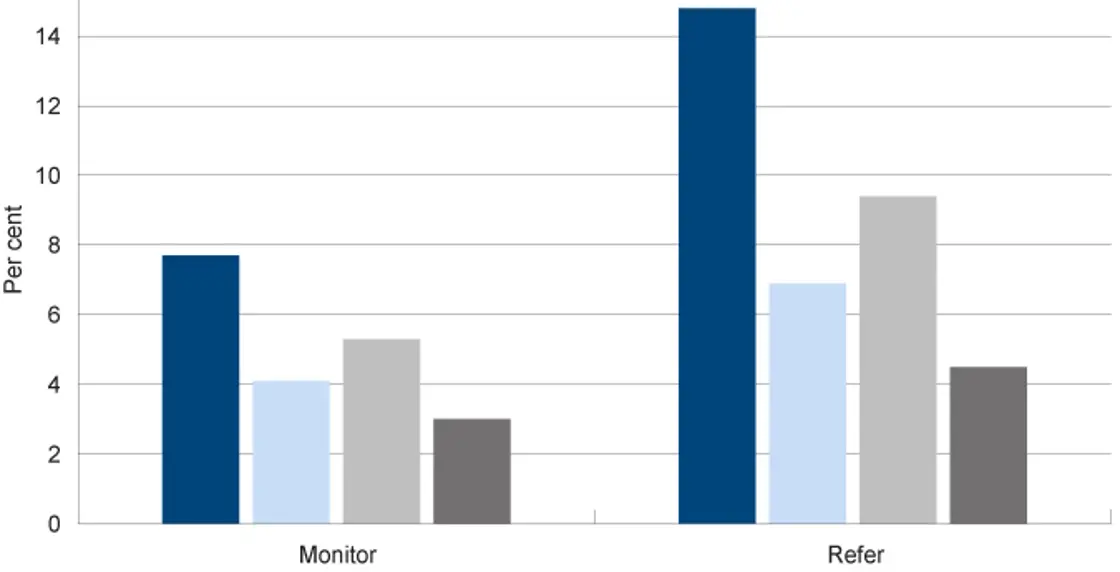

The results of the ASQ:SE2 assessment for attending children aged two years in the Perth metropolitan area are as follows.

|

On track |

Monitor |

Refer |

|

|

Aboriginal |

77.5 |

7.7 |

14.8 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

89.0 |

4.1 |

6.9 |

|

Male |

85.3 |

5.3 |

9.4 |

|

Female |

92.4 |

3.0 |

4.5 |

|

All |

88.6 |

4.2 |

7.2 |

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Note: It is likely that the data is not representative as those children not attending child health checks or being assessed under the ASQ-SE may have different characteristics from those that do attend and are assessed.

Proportion of children at age 2 years with monitor and refer outcomes of ASQ:SE2 questionnaires by selected characteristics, per cent, metropolitan Perth, 2020

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Approximately 11 per cent of assessed children aged two years were recommended for monitoring or referral. A higher number of Aboriginal children were recommended for referral than non-Aboriginal children (14.8% compared to 6.9%) and a higher number of male children were recommended for referral than female children (9.4% compared to 4.5%).

It should be noted that in their recently published report: Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change the Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents found that less than one-in-five children (aged 0 to 12 years) who are referred to a service are accepted for treatment due to high demand, low service availability.19

No data was available on the results of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires® for children in regional and remote WA.

The Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) also provides an indication of the prevalence of mental health issues in a population.20 Data from the 2018 AEDC shows that 7.4 per cent of WA pre-primary students (around five years of age) are developmentally vulnerable on the social competence domain and 7.7 per cent on the emotional maturity domain.21 As with the ASQ:SE2 male children were more likely to be developmentally vulnerable than female children on the social competence domain (10.6% compared to 4.1%) and the emotional maturity domain (12.1% compared to 3.3%).22

The AEDC is increasingly being used in mental health planning and policy discussions.23,24 For further information on AEDC results in WA refer to the Readiness for learning indicator.

Research using the Longitudinal Survey of Australian Children (LSAC) found that a range of independent factors influenced children’s mental health at age four years. They concluded that a complex set of risk factors contribute to child mental health issues including maternal mental health, family income, maternal hostility and temperamental persistence. They also found that the differences in child mental health due to neighbourhood disadvantage and low level of education persisted from age four to 14 years.25

The risk factors for mental health problems in early childhood are complex and bidirectional. For example, growing up in a poor household increases the risk of exposure to poor nutrition, violence, parental drug and alcohol misuse, inadequate education and parental discord – all risk factors for mental health issues.26

A key factor in child and adult mental illness is ‘toxic stress’, which refers to excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and brain.27 Toxic stress can occur when children are repeatedly exposed to abuse, neglect, food scarcity, household dysfunction, violence and/or caregivers with substance abuse or mental health issues.28 Children who have experienced toxic stress in early childhood are more likely to develop significant mental and physical health issues in later life.29 It is therefore not surprising that research shows that children in out-of-home care are significantly more likely to have mental health issues than other children.30

Children in the youth justice system are also more likely to have mental health issues.31 In 2017, a Telethon Kids Institute research team found that 89 per cent of young people in WA’s Banksia Hill Detention Centre had at least one form of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, while 36 per cent were found to have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). While FASD is not a mental illness, it is a cognitive disability which has a significant impact on mental health and increases the likelihood of social and emotional behavioural issues that are often not diagnosed.32,33 It is of significant concern that only two of the young people with FASD had been diagnosed prior to participation in the study.34

Early identification and support for children at risk of mental health issues is critical.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mental Health Australia 2014, Getting the NDIS right for people with psychosocial disability, Mental Health Council of Australia.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, p. 2, 7.

- Rijlaarsdam J et al 2015, Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders in a population-based sample of 5- to 8-year-old children: the impact of impairment criteria, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Vol 24, No 11.

- Feeney-Kettler KA 2010, Screening Young Children’s Risk for Mental Health Problems: A Review of Four Measures, Assessment for Effective Intervention, Vol 35, No 4.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Ibid, p. 18.

- Ibid, p. 144. Note: The researchers noted that DISC-IV is actually recommended for use with children aged six to 18 years, however they determined that it was appropriate for four year-old children in the Australian context.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Quinn P 2015, Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender-specific issues, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol 61, No 5.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Commonwealth of Australia, p. 26.

- Ibid, p. 146.

- Feeney-Kettler KA 2010, Screening Young Children’s Risk for Mental Health Problems: A Review of Four Measures, Assessment for Effective Intervention, Vol 35, No 4.

- Community Health services in WA use the Ages and Stages Questionnaires®, Third Edition (ASQ-3), the Ages and Stages Questionnaires®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2) and in some country health services ASQ TRAK is used. Source: WA Department of Health: Community Health Manual – Ages and Stages Questionnaire.

- The California Evidence-Based Clearing House for Child Welfare 2018, Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Social Emotional (ASQ:SE), viewed 15 January 2018.

- The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents 2021, Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change: Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0–18 in Western Australia, Government of Western Australia, p. 23.

- Centre for Community Child Health (CCCH) 2018, Research Snapshot: Mental health and children’s early learning: why it’s important to think about the combination of difficulties and competence, Australian Early Development Census.

- Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) 2020, Data Explorer, AEDC.

- Custom report from WA Department of Education [unpublished].

- Goldfeld S 2018, Conference Paper: Using the Australian Early Development Census to understand the mental health needs of Australian children, Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Carr VJ et al 2016, New South Wales Child Development Study (NSW-CDS): an Australian multiagency, multigenerational, longitudinal record linkage study, BMJ Open, Vol 6.

- Christensen D et al 2017, Longitudinal trajectories of mental health in Australian children aged 4–5 to 14–15 years, PLoS ONE, Vol 12, No 11.

- Patel V et al 2007, Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge, The Lancet, Vol 369, No 9569.

- Center on the Developing Child 2018, Toxic Stress, Harvard University (website).

- Franke H 2014, Toxic Stress: Effects, Prevention and Treatment, Children, Vol 1.

- Ibid.

- Sawyer M et al 2007, The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 186, No 4.

- Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network and Juvenile Justice NSW 2015, 2015 Young People in Custody Health Survey: Full Report, NSW Government, p. 65.

- Brown J et al 2018, Fetal Alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): A beginner’s guide for mental health professionals, Journal of Neurological Clinical Neuroscience, Vol 2, No 1.

- Pei J et al 2011, Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Journal Of Mental Health, Vol 20, No 5, pp. 438–448.

- Bower C et al 2017, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

Last updated February 2022

Information from the WA Department of Health’s Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provides data on hospital separations1 for children with mental health issues. It also provides information on the number of children who received services from public child and adolescent community mental health services.

Many children with mental health issues will not access mental health services. This is due to a number of reasons including limited availability of affordable services particularly in regional and remote locations, lack of services and programs for children younger than 12 years of age and a low level of community awareness regarding the importance of supporting children’s mental health.2,3

The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents noted in their recently published report: Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change that with regard to mental health services:

“A consequence of demand growing faster than capacity is that every day clinicians are assessing referrals and prioritising access only to the most high-risk children, usually aged between 12-to-15. This has led to proportionally fewer infants and children under the age of 12 being able to access specialist mental health services than in the past, even if they are severely unwell.”

The Taskforce also found that less than one-in-five children (aged 0 to 12 years) who are referred to a service are accepted for treatment. They noted that some health professionals stated they have stopped referring to public mental health services.4

Therefore, the data in this measure will significantly underrepresent the extent of mental health problems experienced by children and young people in the community. However, it does provide some information on service use by very young children.

The following tables provide data for children aged between 0 and four years5 who separated from a WA private or public designated psychiatric hospital or ward, or had a principal diagnosis of mental health conditions.

Caution should be employed when interpreting this data as the numbers are very small. Due to the very low numbers it is not valid to calculate age-specific rates for individual years by regional breakdown, therefore the data does not take into account population increases over time.

|

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total |

|

|

2012 |

21 |

9 |

30 |

|

2013 |

21 |

13 |

34 |

|

2014 |

22 |

8 |

30 |

|

2015 |

17 |

15 |

32 |

|

2016 |

33 |

17 |

50 |

|

2017 |

43 |

8 |

51 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Data only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-codes) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age is based on patient's age at the time of admission into hospital

3. Figures are subject to change.

|

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

|

2012 |

3.5 |

8.6 |

148.1 |

|

2013 |

4.0 |

7.5 |

142.7 |

|

2014 |

3.5 |

8.1 |

118.7 |

|

2015 |

3.7 |

7.8 |

114.0 |

|

2016 |

5.8 |

8.3 |

111.7 |

|

Total |

4.1 |

8.1 |

127.1 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

2. Data only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-codes) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

A very low number of WA children aged 0 to four years (approximately 4 per 100,000) are hospitalised for a mental health issue. The above table highlights the increase in service use as children age, in particular as they enter adolescence.

Most children aged 0 to four years were discharged with a diagnosis of unspecified psychological development. For children aged five to 12 years, the top diagnoses are anorexia nervosa and childhood autism.6

The WA Department of Health also collects data on the number of WA children who received services from public child and adolescent mental health services and programs.

This data only includes public mental health service provision, including outpatient and community mental health services. The public mental health system typically provides services to people with moderate to severe mental health issues, whereas people with mild or emerging mental health issues are often supported by community organisations, support services or primary health providers, for example, general practitioners, counsellors, private practitioners or services such as headspace.

|

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total* |

|

|

2012 |

220 |

91 |

320 |

|

2013 |

220 |

91 |

330 |

|

2014 |

198 |

87 |

331 |

|

2015 |

181 |

82 |

301 |

|

2016 |

213 |

88 |

331 |

|

2017 |

232 |

93 |

359 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System [unpublished]

* Totals do not sum as total includes where patient’s residential address was unknown, no fixed permanent address or residence outside Australia.

Notes:

1. Age Group is based on patient's age at the time of the community mental health service contact.

2. Figures only include patients where the service contact was provided by WA public child and adolescent mental health services.

|

Male |

Female |

|

|

2012 |

184 |

128 |

|

2013 |

179 |

135 |

|

2014 |

191 |

130 |

|

2015 |

179 |

116 |

|

2016 |

186 |

144 |

|

2017 |

210 |

145 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System [unpublished]

* The Hospital Morbidity Data Collection does not capture data on gender but biological sex (male/female).

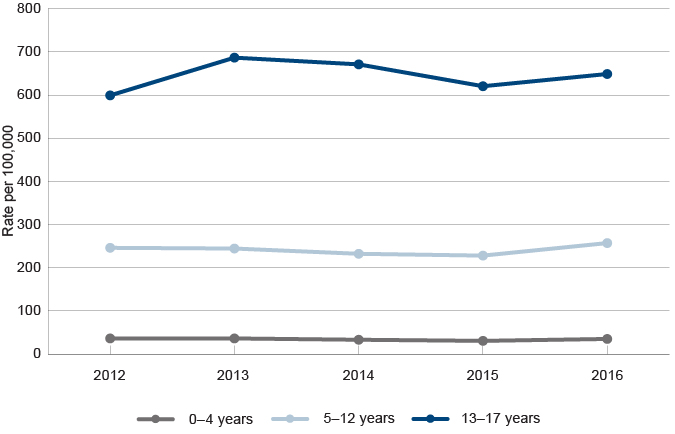

A very low number of young children aged 0 to four years in WA (approximately 34 per 100,000) attend services for a mental health issue. As children age, service use increases, in particular as they enter adolescence. For further information refer to the Mental health indicator for age group 12 to 17 years.

|

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

|

2012 |

36.4 |

246.2 |

599.1 |

|

2013 |

36.4 |

244.5 |

686.5 |

|

2014 |

33.3 |

232.4 |

670.9 |

|

2015 |

30.7 |

228.2 |

620.3 |

|

2016 |

35.2 |

257.2 |

648.7 |

|

Total |

34.4 |

241.7 |

645.1 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of occasions for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rate of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people by selected age groups, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System [unpublished]

Research and numerous inquiries have reported that Aboriginal children and young people are more likely than non-Aboriginal children and young people to have significant mental health issues including self-harm behaviours and suicide.7,8,9 Intergenerational disadvantage, entrenched poverty, crowded housing and high levels of preventable health issues which are present in many Aboriginal communities cause additional stressors or risk factors for Aboriginal children and young people. Additionally, ‘trauma, premature death and grief are experienced at disturbingly high rates in Aboriginal communities’.10

Refer to the Mental health indicator for children aged 6 to 11 years for further discussion of mental health issues for Aboriginal children.

Endnotes

- Hospital separation means the process by which an admitted patient completes an episode of care either by being discharged, dying, transferring to another hospital or changing type of care. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017, Admitted patient care 2015–16: Australian hospital statistics, Health services series no 75, Cat no HSE 185, AIHW p. 282.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, Our Children Can’t Wait – Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Perth.

- The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents 2021, Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change: Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0–18 in Western Australia, Government of Western Australia.

- The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents 2021, Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change: Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0–18 in Western Australia, Government of Western Australia, p. 23.

- This data was provided by the Department of Health for the 0 to four year age group, and not collated for the 0 to five years age group.

- Custom report provided by the Department of Health to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA on the top diagnoses of children and young people separating from a WA public or private hospital with a mental health diagnosis or discharged from a mental health inpatient unit.

- Zubrick, S et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015, Cat No IHW 147, AIHW, p. 80.

- Education and Health Standing Committee 2016, Learnings from the message stick: The report of the Inquiry into Aboriginal youth suicide in remote areas, WA Legislative Assembly.

- WA State Coroner 2019, Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia, WA Government, p. 11.

Last updated February 2022

At 30 June 2021 there were 1,536 WA children in care aged between 0 and five years, more than half of whom (61.3%) were Aboriginal.1

Children in out-of-home care have generally experienced significant adverse events on an ongoing basis. These may include neglect, exposure to family violence and alcohol and drug use, food scarcity and physical or sexual abuse. These factors are primary contributors to children developing mental health issues.

Not surprisingly, research shows that children in out-of-home care are more likely than the general population to have mental health issues.2,3,4

Section 3.4.11 of the Department of Communities Child Protection and Family Support Casework Practice Manual states that when a child of four years or older enters the Chief Executive Officer’s care, they must have an initial medical assessment followed by a more comprehensive health and development assessment. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire5 is recognised as an important tool in this process.

In 2016, the WA Department of Child Protection (now Department of Communities) published the Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015–16 Baseline Indicator Report. The outcomes framework identified the following indicator related to reviewing the mental health of children in out-of-home care: the ‘proportion of children aged four and older who have had an annual health check of their psychosocial and mental health needs’.7

In this report they noted that there were limitations in data accuracy which prevented reporting on this indicator in 2015–16, however, data would be reported in 2016–17.8 No data has been reported on this indicator as at publication date.

There is no data on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA children in care aged between 0 and 5 years.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2021, Custom report provided by Department of Communities, WA Government [unpublished].

- Sawyer M et al 2007, The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 186, No 4.

- NSW Department of Community Services 2007, Mental Health of Children in Out-Of-Home Care in NSW, Australia, Centre for Parenting and Research, NSW Department of Community Services

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists 2015, Position Statement 59: The mental health care needs of children in out-of-home care, The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

- The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is a brief screening tool used to identify behavioural and emotional problems among children and adolescents. Refer to the AIHW Children’s Headline Indicators: Social and Emotional Wellbeing for further information.

- Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015–16 Baseline Indicator Report, p. 10.

- Ibid, p. 10.

Last updated February 2022

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates 9,000 WA children aged 0 to five years (4.4%) had reported disability in 2018.1

There is limited data on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA children with disability aged 0 to 5 years.

Children with intellectual and physical disabilities are more likely to experience mental health issues than the general population.2 A study in the United Kingdom found that children with intellectual disability were four times more likely to have a psychiatric disorder than a child without an intellectual disability.3

Living with disability can contribute to mental health difficulties due to a range of adverse individual and environmental issues associated with disability. These can include experiences of discrimination, bullying and exclusion. Some disabilities can also make it difficult for children to communicate, develop supportive social relationships and self-regulate their behaviour.4

The Commissioner’s 2011 inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people identified gaps in services for children with disability and mental health issues. The Commissioner’s Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia recommended that the Disability Services Commission work with the Mental Health Commission to identify the services required to address the unique needs and risk factors for children with disabilities in a coordinated and seamless manner (Recommendation 25).5

Since that time there have been some changes to services that can cater to young people with complex needs including disability, for example the Young People with Exceptionally Complex Needs program.6 Additionally, the Mental Health Commissioner sponsored ‘A Core Capability Framework: For working with people with intellectual disability and co-occurring mental health issues’ and a National Roundtable on the Mental Health of People with Intellectual Disability was held in March 2018.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) provides funding for children aged under nine years with developmental delay or disability through early childhood partners. The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) recently completed a consultation on the Early Childhood Approach and plans to implement a new Early Childhood Approach in 2021-22.7,8 The NDIS is due to be fully implemented in WA by 2023, and the NDIA is currently reviewing the rollout to some regional and remote areas of WA.9

The implementation of the NDIS should be monitored closely to ensure that all children in WA, regardless of where they live, are able to access the services and supports that they require under the scheme.

For more information on mental health and children and young people with a disability refer to the Commissioner’s paper: The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Children and young people with disability.

Endnotes

- Data is sourced from a custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the Australian Bureau of Statistics based on the 2018 Disability, Ageing and Carers survey. The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities’. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Dix K et al 2013, KidsMatter and young children with disability: Evaluation Report, Flinders Research Centre for Student Wellbeing & Prevention of Violence, Shannon Research Press, p. xi.

- Emerson E and Hatton C 2007, Mental health of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Britain, British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 191.

- Dix K et al 2013, KidsMatter and young children with disability: Evaluation Report, Flinders Research Centre for Student Wellbeing & Prevention of Violence, Shannon Research Press, p. 15.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2011, Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, Our Children Can’t Wait – Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 54.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme 2021, Supporting young children and their families early, to reach their full potential [website].

- National Disability Insurance Scheme 2021, The NDIS in each state: Western Australia [website].

- State of Western Australia and Commonwealth of Australia 2017, Bilateral Agreement between the Commonwealth and Western Australia: Transition to a National Disability Insurance Scheme in Western Australia, National Disability Insurance Agency.

Last updated February 2022

Good mental health is essential to enable children to develop fulfilling relationships, manage change, cope with difficulties and participate successfully in early education.1

There remains a reluctance to acknowledge that very young children can and do experience mental health issues that may manifest as serious social, emotional or behavioural problems (for example, aggression, anxiety and depression). This is supported by a mistaken belief that issues experienced by young children will be outgrown; despite all of the research showing that early childhood experience impacts on lifelong mental health and wellbeing and that intervention at the earliest possible stage will have the most beneficial impact.

Risk factors for mental health issues in young children include poor health in infancy, family violence and disharmony, parental substance misuse, bullying, poverty and physical, sexual and emotional abuse.2 Protective factors include supportive and caring parents, good physical health, a positive school environment, a strong cultural identity and access to high quality and culturally appropriate support services.3

Poor mental health in childhood can set a negative trajectory for ongoing mental health issues in adolescence and adulthood and is associated with a broad range of poor adult health outcomes.4

In 2011, the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA published the Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia which found that the mental health needs of children and young people had not been afforded sufficient priority and there was an urgent need for reform. In 2015, the Commissioner published a follow-up Our Children Can’t Wait report which found that while progress has been made since 2011, significant gaps remain, with children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing far from being comprehensively supported.

In 2021, the National Mental Health Commission released the National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy which recognises the importance of children’s mental health and provides a framework for change to improve the child mental health system.

In WA, the Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0-18 years in Western Australia (Ministerial Taskforce) is considering the public mental health services available in WA and will make recommendations to the WA government.

Research suggests that approximately three-quarters of adult mental illnesses were diagnosed in adolescence and one-half were diagnosed before 15 years of age.5 A recent study estimates that one in 12 infants has risk factors for adult mental illness and one in 40 infants has more than five risk factors.6 Yet, as highlighted by the Ministerial Taskforce, the continuing focus of mental health services for children and young people is to prioritise adolescent treatment services rather than early identification and prevention programs for young children and their families.7

It is fundamentally important that mental health planning places a high priority on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people and their families by providing the full spectrum of services, from prevention to acute services, commencing prior to birth and considering the needs of children at all stages of their development.

This includes providing timely access to effective services for young children and their families, closing the gaps in services for particularly vulnerable children and those with complex and severe mental health needs, developing effective promotion and prevention strategies, and building the capacity for early identification and intervention.

Prevention services and programs need to be targeted to disadvantaged and vulnerable families with young children. This should include a greater focus on quality family and parenting support services that help vulnerable parents manage the demands of parenting across their child’s key life stages.8 There should be a particular focus on parents at risk, including those experiencing mental health issues, family violence or other social health issues, such as poverty. At the same time, the government should undertake a detailed assessment of the availability and effectiveness of existing parenting programs and services in WA.

Children in care, children with disability and Aboriginal children are at a greater risk of experiencing mental health issues. There needs to be a concerted effort to improve services and supports for these children and their families.

In particular, in light of the 2019 Coroner’s report, Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia investment in the prevention and early intervention of mental health issues for Aboriginal children should be a high priority for the WA government.

Data gaps

Limited recent data exists on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA children aged 0 to five years. While identification and diagnosis of mental health issues in very young children is difficult, it is important, as very young children can experience mental health issues that may become more serious social, emotional or behavioural problems in adolescence and adulthood. Additionally, without data highlighting young children’s experiences it is difficult to target programs and services effectively.

There is a need for better data on the prevalence of mental health issues for WA’s young children disaggregated by Aboriginal status and region to enable better targeting of services.

The limited data being collected and reported on the mental health of WA children in care is of concern.

Endnotes

- Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) 2008, Technical Report: The Wellbeing of Young Australians, ARACY, p. 58.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2011, Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 37.

- Ibid, p. 36.

- Department of Health, Mental Health Division (England) 2010, New horizons: confident communities brighter futures: a framework for developing wellbeing, p. 26

- Kim-Cohen J et al 2003, Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective longitudinal cohort, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 60, No 7.

- Guy S et al 2016, How many children in Australia are at risk of adult mental illness?, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 50 No 12.

- The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents 2021, Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change: Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0–18 in Western Australia, Government of Western Australia, p. 22.

- Christensen D et al 2017, Longitudinal trajectories of mental health in Australian children aged 4–5 to 14–15 years, PLoS ONE, Vol 12, No 11.

For further information on mental health of young children refer to the following resources:

- Centre for Community Child Health 2018, Policy Brief: Child Mental Health – A time for innovation, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, Our Children Can’t Wait – Review of the implementation of recommendations of the 2011 Report of the Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Dudgeon P et al 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Commonwealth of Australia.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2015, In Brief: Early Childhood Mental Health, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.