Informal learning opportunities

Parents or carers are a child's first and most enduring teachers and the home environment provides a range of informal learning opportunities and experiences that contribute to a child's learning and development.

Limited data is available on whether all WA children aged 0 to 5 years are provided with quality informal learning opportunities.

Overview

Reading books, singing songs, playing games and doing arts and crafts are all important play activities that parents can do with their children to support their cognitive, emotional and physical development. Providing children with a variety of enriching experiences outside the home is another important component of a stimulating learning environment.

Ensuring the best learning outcomes for WA children involves families and educators working together to support early engagement in learning.

Most WA families regularly engage in reading and learning-related activities in their home and community. The most common informal learning activity is reading books and telling stories.

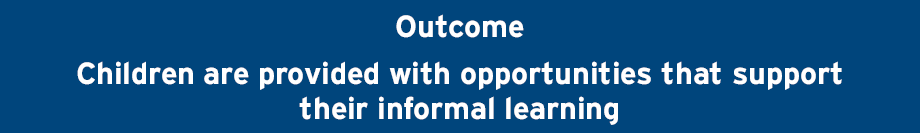

In 2017, most parents (94.9%) engaged in reading activities with their children aged three years and older in the previous week, but fewer parents read to, or with, children younger than three years of age (79.6%).

Proportion of children with parental involvement in reading activities in prior week, per cent, WA, 2011, 2014 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0 and Australian Bureau of Statistics custom report, June 2011

Areas of concern

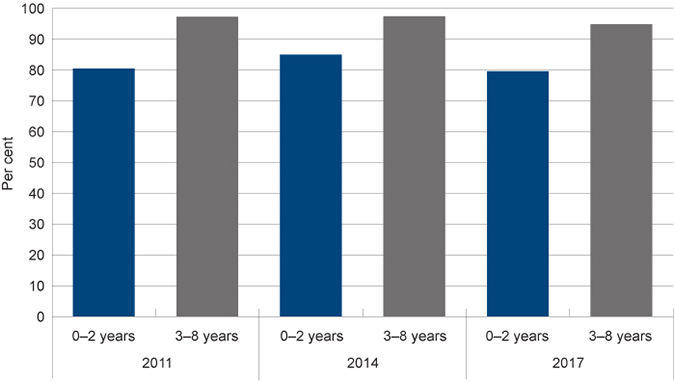

Since 2011, daily reading to 0 to two year-old WA children has decreased (60.5% to 56.5%) and the proportion of children with parents who did not read from a book or tell a story in the last week increased (19.5% to 21.4%).

Proportion of children aged 0 to 2 years with parental involvement by number of days last week parent(s) read from a book or told a story, per cent, WA, 2011 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0 and Australian Bureau of Statistics custom report, June 2011

Last updated November 2018

Research shows that providing a safe, nurturing and stimulating home learning environment during the first three years of life is associated with better cognitive and social outcomes for children as they grow.1,2

The extent to which parents are engaged in their child’s informal learning can be measured by their participation in cognitively-stimulating learning activities and by providing learning materials in the home.

This measure uses data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics Childhood Education and Care survey which captures data for 0 to two year-olds and three to eight year-olds.

|

2011 |

2014 |

2017 |

||||

|

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

|

|

Read from a book or told a story |

80.5 |

80.2 |

85.0 |

80.8 |

79.6 |

83.6 |

|

Watch TV, videos or DVDs |

66.9 |

68.7 |

70.6 |

66.6 |

68.2 |

68.2 |

|

Assisted with drawing, writing or other creative activities |

49.3 |

52.4 |

53.3 |

52.2 |

52.8 |

53.3 |

|

Played music, sang songs, danced or did other musical activities |

77.7 |

77.1 |

84.5 |

78.6 |

78.5 |

78.5 |

|

Physical activities |

62.3 |

65.9 |

68.3 |

61.7 |

64.7 |

68.2 |

|

Attended a playgroup |

26.6 |

20.1 |

28.0 |

20.4 |

20.3 |

21.8 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian Tables 19 Parental involvement in informal learning and Australian Bureau of Statistics custom report, June 2011

|

2011 |

2014 |

2017 |

||||

|

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

|

|

Told stories, read or listened to the child read |

97.3 |

96.3 |

97.5 |

95.9 |

94.9 |

95.4 |

|

Used computers or the internet |

44.1 |

47.2 |

53.7 |

58.6 |

50.5 |

55.4 |

|

Watched TV, videos or DVDs |

89.7 |

88.5 |

81.8 |

84.8 |

83.5 |

85.4 |

|

Assisted with homework or other educational activities |

77.7 |

78.4 |

86.4 |

81.4 |

84.3 |

82.4 |

|

Played sport, outdoor games or other physical activities |

87.0 |

82.2 |

89.0 |

82.1 |

85.6 |

85.2 |

|

Involved in music, art or other creative activity |

67.8 |

65.1 |

71.7 |

63.1 |

70.7 |

66.5 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian Tables 20 Parental involvement in informal learning and Australian Bureau of Statistics custom report, June 2011

In 2017, a large majority of WA parents participated in some form of informal learning activity with their children aged 0 to eight years in the week prior to participating in the survey.

The most common informal learning activity was reading books and telling stories in the home. Parents read or told stories to almost 80 per cent of children aged 0 to two years and read, told stories or listened to the reading of 94.9 per cent of three to eight year-olds.

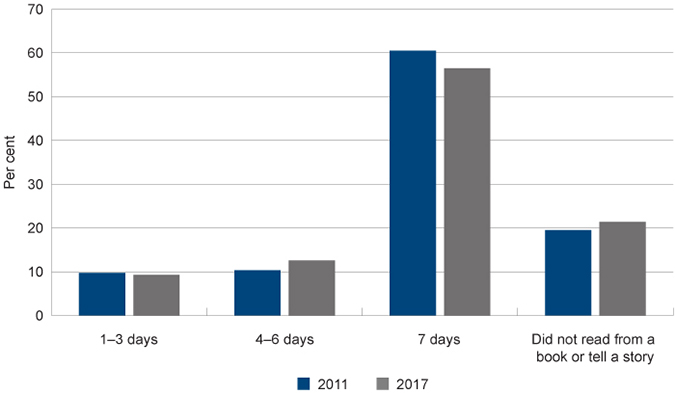

The proportion of WA children with parents engaged in reading activities is marginally lower than in 2014 (and 2011) across both age groups. This reduction contrasts with the result across the rest of Australia, where reading activities for 0 to two year-olds increased and three to eight year-olds remained relatively static from 2014 to 2017.

Proportion of children with parental involvement in children's reading activities by age group, per cent, WA and Australia, 2011, 2014 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian Tables 19 and 20 Parental involvement in informal learning and Australian Bureau of Statistics custom report, June 2011

Among 0 to two year-olds, other common informal learning activities with parents in 2017 included musical activities (78.5%) and watching TV or DVDs (68.2%). Parents of children aged three to eight commonly engaged in sport or outdoor games (85.6%) and assisted with homework or other educational activities (84.3%).

Compared nationally, the proportions and types of activities were largely similar in 2017. Some of the differences evident are that WA parents of 0 to two year-olds were somewhat less likely to engage in physical activities (64.7% compared to 68.2%) or to attend a playgroup with their child (20.3% compared to 21.8%). WA parents of three to eight year-olds were more likely to engage in music, art or other creative activities (70.7% compared to 66.5% nationally) and less likely to use computers or the internet (50.5% compared to 55.4%).

Between 2011 and 2017, there has been an increase in the proportion of WA parents using computers or the internet with children aged three to eight years. Over the same period, there has been a commensurate decrease in the proportion of parents watching TV or DVDs with their children aged three to eight years. This perhaps reflects a shift in the technology, rather than any change in the underlying activity.

While the screen times discussed in this survey are related to learning activities, Australian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years recommend no screen time for children two years old and younger, and no more than one hour per day for children from three to five years-old. For children from three to five years-old, the recommendation is that all of their screen time is educational.3 The recommendation increases to no more than two hours per day for five to 12 year-olds.4

Longitudinal data shows that 44 per cent of Australian children aged four to five years are spending more than the recommended two hours a day on screen-based activities.5 The same research suggests that older children who enjoy doing physical activities will spend less time in front of screens.6 This highlights the importance of engaging young children in fun physical activities to provide the foundation for a more active childhood. For more information on WA children’s health refer to the Physical health indicator.

Activities by family type and labour force status

Children from families experiencing socio-economic disadvantage, those with mothers who speak a language other than English at home and those who live in disadvantaged neighbourhoods can have fewer learning opportunities in the home.7 Further, research shows that family income and parental employment can impact a parent’s ability to provide a rich home learning environment for their young children.8,9

In 2017, parents of 0 to two year-olds where one or no parent was employed were less likely to engage in all informal learning activities with their children than parents in couple families where both parents are employed.

|

2014 |

2017 |

|||||

|

Couple - |

Couple - |

*One-parent families |

Couple - |

Couple - |

*One-parent families |

|

|

Read from a book or told a story |

87.7 |

80.8 |

72.7 |

87.4 |

66.7 |

94.2 |

|

Watch TV, videos or DVDs |

70.5 |

67.0 |

80.2 |

71.7 |

59.6 |

82.7 |

|

Assisted with drawing, writing or other creative activities |

54.2 |

48.9 |

65.8 |

63.8 |

48.5 |

40.4 |

|

Played music, sang songs, danced or did other musical activities |

85.2 |

86.6 |

91.7 |

84.9 |

65.1 |

96.2 |

|

Physical activities |

69.9 |

62.5 |

59.1 |

75.5 |

57.2 |

35.6 |

|

Attended a playgroup |

29.1 |

30.4 |

32.8 |

24.9 |

17.4 |

15.4 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian Table 19 Parental involvement in informal learning

* Employment data is not provided for one-parent families in the WA data

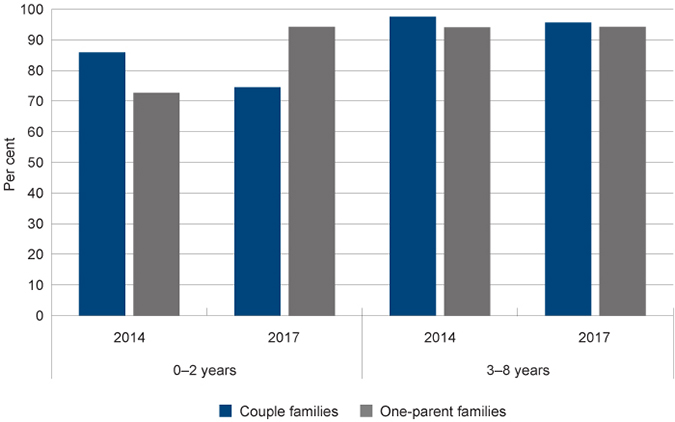

Reading and telling stories to 0 to two year-old children in WA families where one or no parent is employed, has fallen significantly from 80.8 per cent in 2014 to 66.7 per cent in 2017; as has their engagement in musical activities which fell from 86.6 per cent in 2014 to 65.1 per cent in 2017.10

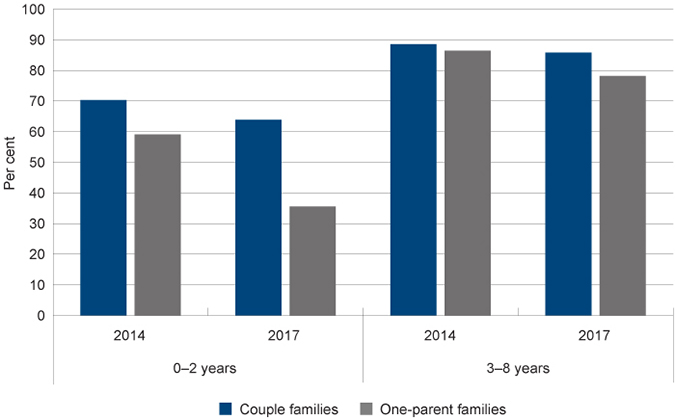

Significantly, in 2017 one-parent families were most likely to engage in reading and musical activities. In 2017, 94.2 per cent of one-parent families of 0 to two year-olds engaged in reading activities and 96.2 per cent engaged in musical activities. However, they were much less likely to engage in physical activities (35.6%) and to assist with drawing and other creative activities (40.4%).

Proportion of children with parental involvement in reading activities by age group and family type, per cent, WA, 2014 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australia Tables 19 and 20 Parental involvement in informal learning

Proportion of children with parental involvement in physical activities by age group and family type, per cent, WA, 2014 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014 and 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australia Tables 19 and 20 Parental involvement in informal learning

The graphs above highlight that activities in the home vary significantly by family type when children are 0 to two years old and become more consistent across family types once children are in the three to eight year-old category. This is in part because five to eight year-old children are in school and their activities are more uniform due to homework and other sports activities.

Daily reading

There is a strong association between reading to children and positive developmental outcomes.11 Parents’ reading and storytelling to children promotes the development of the brain, cognitive skills and children’s reading skills.12,13 Families play an important role in promoting a child’s literacy development and helping them build a strong foundation for future learning in school.14

Daily reading to two and three year-olds is also strongly associated with higher reading performance and numeracy outcomes in Year 3.15 ABS data shows that in WA in 2017, 56.5 per cent of 0 to two year-olds were read to on a daily basis. This is slightly lower than the 57.2 per cent of all Australian children aged 0 to two years who were being read to on a daily basis

|

2011 |

2017 |

|||

|

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

|

|

1 to 3 days |

9.7 |

10.8 |

9.3 |

10.1 |

|

4 to 6 days |

10.3 |

12.2 |

12.6 |

16.2 |

|

7 days |

60.5 |

57.1 |

56.5 |

57.2 |

|

Did not read from a |

19.5 |

19.8 |

21.4 |

16.3 |

Source: Compiled from Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Australian, Table 19 Parental involvement in informal learning and ABS custom request for 2014 and 2018 WA data

Since 2011, daily reading to 0 to two year-old WA children has decreased (60.5% to 56.5%) and the proportion of children with parents who did not read from a book or tell a story in the last week increased (19.5% to 21.4%).

For children in the three to eight year-old age group, 46.8 per cent were being read to or told a story by their parents seven days a week in 2017. This is marginally lower than the national average (47.8%) and represents a significant decrease from the WA results for 2011 and 2014 (52.0% and 55.0%).

|

2011 |

2014 |

2017 |

||||

|

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

|

|

1 to 3 days |

10.5 |

14.5 |

12.4 |

15.4 |

8.0 |

14.4 |

|

4 to 6 days |

34.8 |

33.3 |

30.0 |

30.5 |

40.0 |

33.4 |

|

7 days |

52.0 |

48.5 |

55.0 |

50.0 |

46.8 |

47.8 |

|

Did not read from a |

2.7 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

4.4 |

Source: Compiled from Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian, Table 20 Parental involvement in informal learning and ABS custom request for 2014 data

Older children are less likely to be read to or told a story every day of the week if both parents are employed (46.5%) compared to families in which one or no parent is employed (52.1%).

|

Couple family |

|||||

|

Both parents employed |

One or no parent employed |

Total couple families |

One-parent families |

Total children |

|

|

1 to 3 days |

9.3 |

4.4 |

8.8 |

10.3 |

8.0 |

|

4 to 6 days |

39.8 |

41.6 |

39.6 |

46.4 |

40.0 |

|

7 days |

46.5 |

52.1 |

49.5 |

38.2 |

46.8 |

|

Did not read from a book or tell a story |

4.6 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

4.2 |

3.0 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian, Table 20 Parental involvement in informal learning

As well as providing educational interactions and activities, parents provide a stimulating home learning environment by making learning materials such as books, available at home.16 The number of books in a family’s home is positively related to a child’s reading ability.17 Research has found that the greater the number of books the greater the benefit, however, as few as 20 books in the home still has a significant impact.18

In 2017, around 80 per cent of WA children aged three to eight years had more than 25 children’s books in their home. At the same time, 8.4 per cent of children aged 0 to two years had less than 10 children’s books in the home.19

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

0 to 2 years |

3 to 8 years |

0 to 2 years |

3 to 8 years |

|

|

Less than 10 |

8.4 |

3.6* |

8.7 |

2.7 |

|

10 to less than 25 |

23.2 |

13.6 |

20.2 |

12.8 |

|

25 to less than 100 |

52.4 |

39.6 |

44.2 |

43.3 |

|

100 to less than 200 |

15.9 |

28.9 |

25.9 |

30.3 |

|

200 or more |

N/A |

12.0 |

N/A |

10.0 |

Source: Compiled from Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian, Tables 19 and 20 Parental involvement in informal learning and custom request for additional data on informal learning of children aged 0-2 years [unpublished].

*Estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

Since 2011, there has been a significant decrease in the number of children with more than 100 books in the home. There has been a corresponding increase in the proportion of WA children with more than 10 and less than 100 children’s books in the home.

|

2011 |

2017 |

|||

|

0 to 2 years |

3 to 8 years |

0 to 2 years |

3 to 8 years |

|

|

Less than 10 |

* |

1.8 |

8.4 |

3.6* |

|

10 to less than 25 |

21.8 |

8.9 |

23.2 |

13.6 |

|

25 to less than 100 |

43.3 |

40.9 |

52.4 |

39.6 |

|

100 to less than 200 |

27.6 |

36.8 |

15.9 |

28.9 |

|

200 or more |

N/A |

11.3 |

N/A |

12.0 |

Source: Compiled from Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0, Western Australian, Table 20 Parental involvement in informal learning (aged 3-8 years) and custom request for additional data on informal learning of children aged 0 – 2 years [unpublished]

*Estimate has a high relative standard error and therefore has been suppressed.

To date, research and data has focused on the number of books in the home, yet there are other mechanisms for children to engage in reading activities. In particular, books can be borrowed from the library and/or electronic books can be accessed. No data is available on the number of children’s books borrowed from WA libraries or the number of books accessed through tablets or other electronic media. Research on the benefits or weaknesses of electronic books on children’s outcomes is still in its infancy.20

The Better Beginnings program is a WA-based family literacy program run by the State Library of WA which supplies families with reading packs. In 2016-17, 95 per cent of WA families with a newborn baby received a Better Beginnings reading pack which supports parents to read to their children from birth.21 Furthermore, since the program started, more than 30,000 reading packs have been distributed to families in approximately 100 remote communities across WA.22

The ABS Childhood Education and Care data is not available disaggregated by Aboriginal status. Data on early learning in the home among Aboriginal families across Australia is available through the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) conducted through the Department of Social Services.

LSIC data reports that in 2012, 34.9 per cent of surveyed Aboriginal children aged four to eight years had more than 50 children’s books in the home and 13.1 per cent had five or fewer. 84.2 per cent of Aboriginal children aged four to five years had been read a book by someone in the last week.23

Overall, the LSIC researchers determined that levels of parental involvement were found to be higher in parents with higher education levels, partnered parents, parents who were receiving an income from wages and salaries, and families living in urban areas.24 These findings mirror the impact of family disadvantage for the population more broadly and highlight that the high percentage of Aboriginal children who have lower academic outcomes is directly related to the higher proportion of Aboriginal families that are economically vulnerable and disadvantaged.25

The LSIC data cannot be directly compared with other data for this measure and WA data would differ from the national average due to the different demographic characteristics of Aboriginal children living in WA; that is, a greater proportion living in remote and very remote communities.

Endnotes

- Rodriguez ET et al 2009, The formative role of home literacy experiences across the first three years of life in children from low-income families, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, Vol 30 No 6.

- Kernan M 2012, Parental Involvement in Early Learning: a review of research, policy and good practice, Bernard Van Leer Foundation and International Child Development Initiatives, p. 19.

- Department of Health, Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines – Frequently Asked Questions, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Health, Australia's Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2016, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2015 Report, Chapter 5: Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 102.

- Ibid, p. 119-120.

- Yu M and Daraganova G 2015, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2014 Report, Chapter 4: Children’s early home learning environment and learning outcomes in the early years of school, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 77.

- Warren D and Edwards B 2017, Contexts of Disadvantage, Occasional Paper No. 53, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. xi.

- Yu M and Daraganova G 2015, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2014 Report, Chapter 4: Children’s early home learning environment and learning outcomes in the early years of school, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 69.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, Cat No 4402.0, Table 19 Parental involvement in informal learning and Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2014, Cat No 4402.0, Table 19 Parental involvement in informal learning.

- Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and Melbourne Institute of Applied Economics and Social Research 2014, Reading to young children: A head-start in life.

- Hutton JS et al 2015, Home Reading Environment and Brain Activation in Preschool Children Listening to Stories, American Academy of Paediatrics, Vol 136, No 3.

- Kalb G and van Ours JC 2012, Reading to young children: a head-start in life, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, p. 24.

- Yu M and Daraganova G 2015, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2014 Report, Chapter 4: Children’s early home learning environment and learning outcomes in the early years of school, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p.78.

- Ibid, p. 77.

- Bradley R and Caldwell B 1995, Caregiving and the regulation of child growth and development: Describing proximal aspects of the caregiving systems, Developmental Review, Vol 15, No 1.

- Evans M et al 2014, Scholarly culture and academic performance in 42 nations, Social Forces, Vol 92, No 4, pp. 1573–1605.

- University of Nevada, Reno 2010, Books in home as important as parents' education in determining children's education level, ScienceDaily, 21 May 2010 [website].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, Cat No. 4402.0, Western Australian and Australian, Table 20 Parental involvement in informal learning for years 2017 and 2014.

- Reich SM et al 2016, Tablet-Based eBooks for Young Children: What Does the Research Say? Journal Of Developmental And Behavioral Pediatrics, Vol 37, No 7, pp. 585–591.

- State Library of Western Australia 2017, Annual Report 2016-2017 of the Library Board of Western Australia, 65th Annual Report of the Board, Government of Western Australia.

- Better Beginnings, Better Beginnings for remote Aboriginal communities [website], viewed 16 October, 2018.

- National Centre for Longitudinal Data 2016, Parents involvement in education of Indigenous children, Research summary No. 5/2016, from Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children—Wave 5, Department of Social Services.

- Ibid.

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2018, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2014 Report, 2.09 Index of disadvantage, [website].

Infants and young children who have been exposed to abuse and neglect are at a high risk of adverse health and wellbeing outcomes over their lifetimes and quality informal learning opportunities are critical to their future wellbeing.

At 30 June 2019, there were 1,341 WA children in care aged between 0 and four years, more than one-half of whom (56.8%) were Aboriginal.1

No data exists that examines the participation of carers of WA children in care aged between 0 and five years in informal learning activities.

The Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study (POCLS) is a longitudinal study on out-of-home care (OOHC) in NSW examining the developmental wellbeing of children and young people aged 0 to 17 years.2 The study collects data on how often caregivers engage in learning and play activities with children, as well as activities that children participate in outside of the home, such as playgroup and library activities.

Preliminary findings in this NSW study show that 88 per cent of carers of children aged nine to 35 months played with toys or games indoors at least six days in the past week. This was the most frequently cited activity. Yet only 48.8 per cent of carers read to children aged nine to 35 months from a book at least six days a week. This increased to 53 per cent of carers reading to children aged three to five years. A significant proportion (26.6%) of carers of children aged nine to 35 months either did not read to their child in the last week (prior to the survey) or only on one to two days. This decreased to 19.3 per cent for carers of children aged three to five years.3

For WA children in care, there is no data that examines the quality and frequency of their participation in informal learning opportunities with their carers.

More information is required on informal learning opportunities for children in care in WA.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018-19, WA Government p. 26.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies et al 2015, Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study: Outcomes of children and young people in Out-of-Home care in NSW Wave 1 baseline statistical report, NSW Department of Family and Community Services.

- Ibid, p. 124.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers data collection reports that approximately 5,200 WA children and young people (3.1%) aged 0 to four years have a reported disability.1

Stimulating home environments and relationships are vital for nurturing the growth, learning and development of children. In the case of children with disability, parents and carers may also need to respond to the specific developmental needs of their child, seeking guidance or intervention from allied health professionals and obtaining support or respite as required.

No data exists on the participation of children with disability in informal learning with their parent or carer.

Endnotes

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Disability, Ageing and Carers: 2018, Western Australia, Table 1.1 and 1.3.

Parents have an important role to play in their child’s developmental and educational outcomes but the extent and form of their engagement is strongly influenced by a family's social class, the mother’s education level and psychosocial health as well as single parent status and family ethnicity.1,2 Research shows that families experiencing disadvantage are less able to provide a cognitively stimulating home environment or to receive informal support from family and friends compared to more highly educated and working parents.3,4

Parents and caregivers who engage regularly in home learning can contribute significantly to their child’s learning and development.5,6 Longitudinal research indicates a direct causal effect from reading to young children and future schooling outcomes regardless of parental income, education level or cultural background.7 By reading frequently to their young children and investing in cognitively stimulating activities, parents have a decisive role to play in the developmental and educational outcomes of their children.

Parents and families require support, education and resources to help them create an enriching home learning environment for their young children.8,9 Mothers’ groups and play-groups,10 parenting classes and quality early education and care programs are all part of an effective approach to supporting parents to enhance children’s learning and development in the early years.

Improving the early home environment for children in vulnerable families can help overcome the effects of disadvantage on a child’s developmental outcomes.11

Intervention programs, such as visiting parenting support programs and programmed educational home activities, can improve parents’ ability to engage in behaviours that support their children’s early learning.12 An example of this is the Better Beginnings Family Literacy Program, a state-wide family literacy program that aims to support the literacy development of children throughout WA by providing parents with the tools and resources required to build language and literacy skills from birth.

At the same time, early childhood programs and services provided in welcoming and integrated settings, such as children and family centres, can be an effective way to provide parents with easier access to services and support.13

Data gaps

This indicator relies on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Childhood Education and Care Survey, which is only conducted every three years. The survey data is also not able to be disaggregated by region in WA or by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal parents and children.

Additional information is required on children’s screen time activities, in particular more data on educational versus non-educational screen time.

Endnotes

- Warren D and Edwards B 2017, Contexts of Disadvantage, Occasional Paper No. 53, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Kernan M 2012, Parental Involvement in Early Learning: a review of research, policy and good practice, Bernard Van Leer Foundation and International Child Development Initiatives.

- Heckman J 2006, Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children, Science Vol 312, No 5782.

- Kernan M 2012, Parental Involvement in Early Learning: a review of research, policy and good practice, Bernard Van Leer Foundation and International Child Development Initiatives, p. 7.

- Pascoe S and Brennan D 2017, Lifting our game: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools through Early Childhood Interventions, VIC Government.

- Inouk E et al 2017, The Role of Home Literacy Environment, Mentalizing, Expressive Verbal Ability, and Print Exposure in Third and Fourth Graders’ Reading Comprehension, Scientific Studies of Reading, Vol 21, No 3.

- Kalb G and van Ours JC 2012, Reading to young children: a head-start in life, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research.

- Kernan M 2012, Parental Involvement in Early Learning: a review of research, policy and good practice, Bernard Van Leer Foundation and International Child Development Initiatives.

- Kiernan KE and Mensah FK 2011, Poverty, family resources and children's early educational attainment: The mediating role of parenting, British Educational Research Journal, Vol 37, No 2, pp. 317-336..

- For more information on the benefits of playgroups, see Gregory T et al 2016, It takes a village to raise a child: The influence and impact of playgroups across Australia, Telethon Kids Institute.

- Warren D and Edwards B 2017, Contexts of Disadvantage, Occasional Paper No. 53, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- OECD 2012, Encouraging Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Research Brief: Parental and Community Engagement Matters, OECD.

- Moore T 2008, Evaluation of Victorian children’s centres: Literature review, Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

For more information on informal learning refer to the following resources:

- Centre on the Developing Child 2007, InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development, Harvard University [website], viewed 25 February 2020.

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations 2009, Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia, Council of Australian Governments.

- Yu M and Daraganova G 2015, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 2014 Report, Chapter 4: Children’s early home learning environment and learning outcomes in the early years of school, Australian Institute of Family Studies.