School attendance

Regular attendance and engagement in school is important for the development of intellectual and social emotional skills and contributes significantly to educational outcomes. Through primary school, children are expected to acquire the foundational skills that will prepare them for future progress through the education system.

Last updated May 2020

Good data is available on whether WA children aged 6 to 11 years are attending school.

Overview

While engagement with school and learning is multifaceted, absence is a marker of disengagement and helps predict school completion and future engagement in work or further study.1 A higher rate of absence is also directly related to a lower level of academic achievement.2

In the Commissioner’s Speaking Out Survey 2019, 68.4 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students in WA said it was very important to them to be at school every day.

In the same study, a higher proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students said being at school every day was very important (71.8% compared to 68.1%) but the difference was not statistically significant.

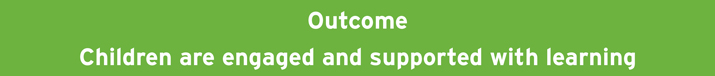

Most children and young people have high attendance rates at school. However, in 2019 WA reported the lowest overall attendance rate for Year 4 to Year 6 students for the past six years (92.1%).

Attendance rates of students in Year 1 to Year 6, WA and Australia, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority (ACARA), National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

Areas of concern

Aboriginal students in WA have a significantly lower attendance rate than non-Aboriginal students (79.8% compared to 93.1%).

In 2019, only 41.1 per cent of WA Aboriginal students attended for at least 90 per cent of the time (compared to 77.8% of non-Aboriginal students).

Endnotes

- The Smith Family 2018, Attendance lifts achievement: Building the evidence base to improve student outcomes, March 2018, The Smith Family.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Last updated May 2020

Pre-primary attendance

In WA Pre-primary is the first compulsory year of schooling. Children who have turned five years of age by 30 June attend Pre-primary that year, those who turn five after 30 June attend in the following year.

Data items for Pre-primary enrolment and attendance have been included in the age group of 6 to 11 years to reflect that it is the first year of compulsory schooling and the research and policy approaches are relevant for all of primary school. For information on children aged 0 to 5 years, including data from the Australian Early Development Census, refer to the Indicator Readiness for learning for the 0 to 5 years age group.

|

Government |

Non-government |

Total |

|||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

||

|

2014 |

24,877 |

73.5 |

8,954 |

26.5 |

33,831 |

|

2015 |

25,225 |

73.6 |

9,049 |

26.4 |

34,274 |

|

2016 |

25,364 |

74.0 |

8,922 |

26.0 |

34,286 |

|

2017 |

25,300 |

74.1 |

8,846 |

25.9 |

34,146 |

|

2018 |

26,096 |

75.0 |

8,685 |

25.0 |

34,781 |

|

2019 |

26,001 |

74.7 |

8,792 |

25.3 |

34,793 |

Source: WA Department of Education, Statistical reports, Number of primary and full-time secondary students over the past 10 years – by school education (public and non-government) sector and year level

Note: Enrolments as at Semester 2 student census each year. Government includes community kindergarten students. Non-government includes independent pre-school students.

Three-quarters (74.7%) of enrolled WA children attend Pre-primary in government schools. Since 2014, there has been a slight shift in the number of Pre-primary enrolments from the non-government to the government sector.

In 2017, only 73.1 per cent of Pre-primary students attended regularly. These proportions have increased slightly since 2014. The term ‘regular attendance’ denotes students who attend 90 per cent or more of the available days.

|

All students |

Aboriginal students |

|

|

2014 |

70.1 |

35.2 |

|

2015 |

72.8 |

35.7 |

|

2016 |

73.0 |

38.3 |

|

2017 |

73.1 |

38.6 |

Source: Data provided by WA Department of Education, custom report [unpublished]

Attendance for Aboriginal students has been slowly improving since 2014, however, in 2017 only 38.6 per cent of Aboriginal students enrolled in Pre-primary in government schools were recorded to regularly attend (more than 90 per cent of the time). Irregular attendance at this level significantly affects a child’s foundation for learning and contributes to the gap in educational outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

Compulsory Pre-primary attendance was introduced in WA in 2013. The low attendance levels for all students at Pre-primary is perhaps reflective of this change in policy and practice. Recent research has found that children from disadvantaged communities were more likely to not attend Pre-primary than those living in the most advantaged communities.1 How parents and children are experiencing the change to compulsory attendance in WA and why attendance levels in Pre-primary are lower than Primary school levels would be a valuable topic for further research.

Primary school attendance

School attendance for students in Year 1 to Year 10 is collected annually through the data set National Student Attendance Data Collection (ACARA - administrative data). This is across all school sectors and jurisdictions in Australia.

Attendance is commonly reported through two measures, attendance rate2 and attendance level.3 The attendance rate measures the average time students attend school as a proportion of the total number of possible student days. The attendance level records the proportion of students who attend 90 per cent or more of the available days and is therefore useful for identifying the degree of consistent attendance.

The attendance rate for all WA Year 1 to Year 6 students has decreased by one percentage point from 93.1 per cent in 2018 to 92.1 per cent in 2019, which is lower than the national average for 2019 of 92.4 per cent4 and the lowest rate recorded in WA for the past six years.

The Department of Education notes that the particularly early and severe flu season impacted attendance data in 2019 and without that attendance rates would have been similar to previous years.

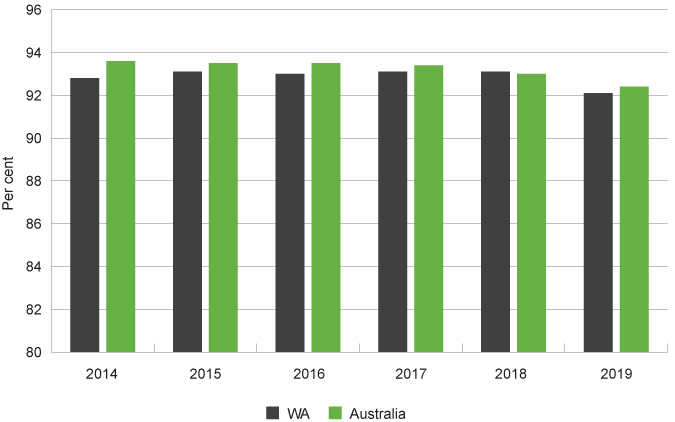

The decrease in attendance rates is evident for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students. The 2019 rates are below the rates for 2018 for both cohorts and are the lowest measured over the past six years (Aboriginal students: 79.8% compared to non-Aboriginal students: 93.1%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

2014 |

81.0 |

93.6 |

92.8 |

|

2015 |

81.3 |

94.0 |

93.1 |

|

2016 |

80.9 |

93.9 |

93.0 |

|

2017 |

81.3 |

94.0 |

93.1 |

|

2018 |

81.0 |

94.0 |

93.1 |

|

2019 |

79.8 |

93.1 |

92.1 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

Attendance rates for students in Year 1 to Year 6 by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

The overall proportion of students who attend 90 per cent or more of the available days (attendance level) for all WA students decreased from 79.7 per cent in 2018 to 75.2 per cent in 2019.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

2015 |

44.3 |

82.3 |

79.6 |

|

2016 |

44.2 |

81.7 |

79.1 |

|

2017 |

45.1 |

82.2 |

79.6 |

|

2018 |

45.0 |

82.3 |

79.7 |

|

2019 |

41.1 |

77.8 |

75.2 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

It is of particular concern that only 41.1 per cent of Aboriginal Year 1 to Year 6 students attend for at least 90 per cent of the time compared to 77.8 per cent of non-Aboriginal students. Furthermore, the attendance level of Aboriginal students (41.1%) in WA is below the level recorded for Aboriginal students nationally (52.1%).5

Notably, attendance levels for non-Aboriginal students in WA also decreased markedly from 82.3 per cent in 2018 to 77.8 per cent in 2019.

There is a significant difference in attendance rates and levels between WA students in metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas with both measures decreasing relative to a student’s distance away from the metropolitan area.

Male students have a slightly lower attendance rate and level than female students across all geographic areas.

|

Attendance rate |

Attendance level |

|||||

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Metropolitan |

92.8 |

93.0 |

92.9 |

77.6 |

78.1 |

77.8 |

|

Inner regional |

91.5 |

91.9 |

91.7 |

71.1 |

72.1 |

71.6 |

|

Outer regional |

90.6 |

91.3 |

90.9 |

68.4 |

70.6 |

69.4 |

|

Remote |

88.3 |

89.0 |

88.6 |

62.8 |

64.9 |

63.8 |

|

Very remote |

77.1 |

78.5 |

77.8 |

40.1 |

43.3 |

41.7 |

|

All |

92.0 |

92.3 |

92.1 |

74.8 |

75.6 |

75.2 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

There are significant regional differences in attendance rates between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students. For example, the attendance rate for Aboriginal students in very remote WA is only 66.6 per cent compared to 84.6 per cent in the metropolitan area.

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Metropolitan |

84.6 |

93.3 |

87.4 |

93.1 |

|

Inner regional |

84.9 |

92.1 |

88.4 |

92.5 |

|

Outer regional |

82.4 |

92.3 |

85.2 |

92.4 |

|

Remote |

78.1 |

92.1 |

78.1 |

91.5 |

|

Very remote |

66.6 |

91.6 |

65.8 |

90.8 |

|

All |

79.8 |

93.1 |

84.5 |

93.0 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

Of particular concern is that only 19.7 per cent of Aboriginal students in very remote WA attend primary school for at least 90 per cent of the time.

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Metropolitan |

49.6 |

79.0 |

57.3 |

78.9 |

|

Inner regional |

48.0 |

73.1 |

60.3 |

76.3 |

|

Outer regional |

44.1 |

73.6 |

51.6 |

75.1 |

|

Remote |

38.6 |

72.3 |

38.2 |

71.2 |

|

Very remote |

19.7 |

68.9 |

21.9 |

68.3 |

|

All |

41.1 |

77.8 |

52.1 |

78.0 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

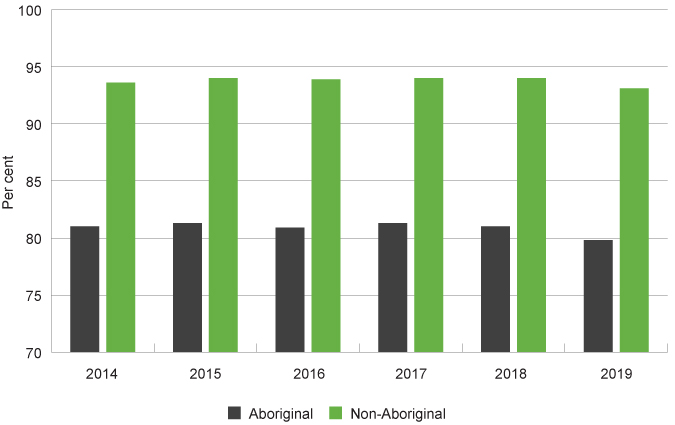

The gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal attendance rates and levels generally increases relative to students’ distance from the metropolitan area. The attendance rate gap is lowest in inner regional areas (7.2 percentage points), whereas in very remote areas the difference widens to 25.0 percentage points.

Attendance gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 1 to Year 6 students by remoteness area, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

WA children from low socioeconomic backgrounds, Aboriginal students, students who change schools often and those whose parents have lower levels of education and occupational status, have lower levels of attendance, on average.6 The factors that create these differences in attendance are often in place before children start primary school. Research shows that the gap generally remains constant throughout primary school and that it can widen.7 Refer to the Telethon Kids Institute report: Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts for further information.

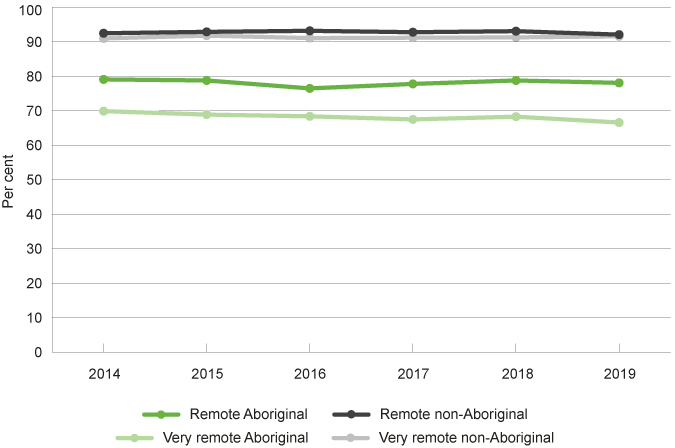

There has been little change in attendance rates in remote areas since 2014 for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students. In very remote areas attendance rates for Aboriginal students have decreased since 2014 (69.9% compared to 66.6% in 2019), while for non-Aboriginal students they have remained relatively stable.

|

Remote |

Very remote |

|||

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

2014 |

79.1 |

92.5 |

69.9 |

91.0 |

|

2015 |

78.8 |

92.9 |

68.9 |

91.8 |

|

2016 |

76.5 |

93.2 |

68.4 |

91.1 |

|

2017 |

77.8 |

92.8 |

67.5 |

91.2 |

|

2018 |

78.8 |

93.1 |

68.3 |

91.3 |

|

2019 |

78.1 |

92.1 |

66.6 |

91.6 |

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

Attendance rates for Year 1 to Year 6 students in remote and very remote areas by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority, National Report on Schooling 2019 – Student Attendance dataset

In May 2014, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to close the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal school attendance within five years (by 2018). While many Aboriginal students are attending school, the 2020 Closing the Gap report notes that Australia, including WA, did not meet this target.8

For further information refer to the Commissioner’s Policy Brief on Aboriginal children and young people and education. For a discussion of the issues specifically impacting Aboriginal students’ attendance refer to the Closing the Gap Clearing House report, School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students and for additional information on the extent to which multiple disadvantage can impact Aboriginal children refer to the National Centre for Longitudinal Data – Multiple Disadvantage paper.

Children and young people engaging in difficult or challenging behaviour

Research shows that regular attendance at school is critical for children and young people to reach their full potential. However, schools do use suspensions and exclusions when students exhibit certain behaviours. Exclusion means a student can no longer attend a particular school, and another school or education program is found for them.

Reasons for suspensions and exclusions can include damage to or theft of property, violation of a school’s code of conduct or school/classroom rules as well as physical aggression, and abuse of staff and other students.

In 2018, 14,243 primary school and high school students (4.5% of total enrolments) were suspended, compared to 14,075 students (4.5% of total enrolments) in 2017.

|

Number |

Per cent of enrolments |

|

|

2016 |

12,649 |

4.3 |

|

2017 |

14,075 |

4.5 |

|

2018 |

14,243 |

4.5 |

Source: WA Department of Education, Annual Report 2018–19

There were 24 exclusions in 2018.9 This represents a substantial increase from 2017 and 2016 when there were eight exclusions in each year.10

Evidence suggests that suspensions and exclusions can have unintended consequences of further entrenching problematic behaviour, as extended time away from school can result in students falling further behind and becoming even more disengaged.11

Children who are excluded or are otherwise disengaged from mainstream schooling have several alternative education options.

The School of Special Educational Needs: Behaviour and Engagement (SSEN:BE) provides educational support and services for students with extreme, complex and challenging behaviours. The SSEN:BE incorporates the Midland Learning Academy and 13 engagement centres.12 In 2018, 27 severely disengaged students were enrolled at the Midland Learning Academy (an increase from 21 students in 2017).13 In 2018, a total of 745 students were supported by engagement centres across WA.14

Regular attendance is critical for these students, however, due to the complexity of their circumstances, attendance rates for these students are not comparable to other students in WA.

Non-government Curriculum and Reengagement in Education (CARE) schools are also available, which cater to young people in secondary school who are marginalised from mainstream education. Approximately 2,100 WA students were enrolled in CARE Schools in Semester 2, 2019.15 Attendance is a key focus for staff at CARE schools as the students enrolled in these schools have often had very low attendance rates in the past. Information on student attendance for each CARE school is generally provided in their performance or annual reports.

Children and young people with medical or mental health issues

For some students, a medical or mental health issue prevents them from successfully participating in mainstream school programs, in this case, the School of Special Educational Needs: Medical and Mental Health (SSEN:MMH) provides educational programs and services. Support is available for both public and private school students and includes educational programs at Perth Children’s Hospital, within the home or to support transition to the student’s enrolled school. In 2018, the SSEN:MMH had over 60 programs servicing over 5,565 students.16

Students engaging with SSEN:MMH services generally have lower attendance rates than the broader student population. The attendance rates of students in contact with SSEN:MMH services during only one semester will usually return to pre-contact levels.17 Those students engaged with SSEN:MMH services over multiple semesters, due to more significant medical or mental health issues, will generally continue to have lower attendance rates than the broader student population.18

Children and young people in Banksia Hill Detention Centre

Approximately 134 children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years were held in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre on an average day during 2018–19.19 Education services at Banksia Hill are not managed by the WA Department of Education and attendance rates are not available.

In July 2017, the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services inspected the Banksia Hill Detention Centre and concluded that the education services delivered at Banksia Hill did not meet community standards.20 The Inspector noted that following some critical incidents in May 2017 the education centre was closed, and at the time of their review full-time education had not yet been restored in July 2017. In their review, they noted that based on observation of classrooms and feedback from staff and young people many students had disengaged from the learning program and were playing card games or doing colouring-in activities during class times.

The Inspector recommended that if significant improvements were not made over the next three years, serious consideration should be given to transferring responsibility for education at Banksia Hill to the Department of Education.21

The Productivity Commission reported that for the 2018–19 year 97.0 per cent of children and young people of compulsory school age in Banksia Hill were attending an education course. This represents a significant improvement on 2017–18 when only 73.0 per cent of children and young people of compulsory school age were attending an education course.22 This report does not, however, provide information on attendance rates or levels.

All children have the right to an education and for children and young people held in a detention facility continuation of their schooling is particularly important as otherwise it will leave them unprepared or even unable to return to school and learning upon release.

Endnotes

- O’Connor M et al 2020, Trends in preschool attendance in Australia following major policy reform: Updated evidence six years following a commitment to universal access, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol 51.

- The student attendance rate, KPM 1 (b), is defined as the number of actual full-time equivalent student-days attended by full-time students in Years 1 to 6 as a percentage of the total number of possible student-days that students could have attended over the period.

- The student attendance level, KPM 1(c), is defined as the proportion of full-time students in Years 1 to 6 whose attendance rate is greater than or equal to 90 per cent over the period of Semester 1 of the reporting year (from 2015).

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2020, Student attendance dataset, ACARA.

- Ibid.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Ibid.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Closing the Gap Report 2020,Commonwealth of Australia.

- WA Department of Education 2019, Annual Report 2018–19, WA Government.

- Ibid.

- Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People 2019, What children and young people in juvenile justice centres have to say, NSW Government.

- WA Department of Education, School of Special Educational Needs: Behaviour and Engagement [website].

- WA Department of Education 2019, Annual Report 2018–19, WA Government.

- WA Department of Education 2019, School of Special Educational Needs: Behaviour and Engagement 2018 Annual Report, WA Government.

- WA Department of Education 2018, Alphabetical List of Australian Schools with enrolment numbers at Semester 2 2019. CARE Schools were identified from a WA Department of Education list of Alternative Education Programs: CARE Schools combined with a google search.

- WA Department of Education 2019, School of Special Educational Needs: Medical and Mental Health: 2018 Annual Report.

- WA Department of Education 2018, School of Special Educational Needs: Medical and Mental Health: 2017 Annual Report.

- Ibid.

- WA Department of Justice 2019, Annual Report 2018–19, WA Government, p. 27.

- Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services 2018, 2017 Inspection of Banksia Hill Detention Centre, WA Government.

- Ibid.

- Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services: Youth Justice, Table 17A.13 Proportion of young people in detention attending education and training, by Indigenous status, Australian Government.

Last updated May 2020

While attendance rates and levels provide an objective measure of school attendance, it is also critical to understand how students view school and their perspectives on the importance of attending school. This represents a valid measure of student’s engagement and their likely participation.

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.1

Students in Year 4 to Year 6 generally perceived being at school every day to be important – almost 70 per cent of students said it was very important and 27.1 per cent said it was somewhat important to them to be at school every day. However, almost five per cent (4.5%) responded that it is not very important to them.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Very important |

66.1 |

70.9 |

68.5 |

67.4 |

69.8 |

68.4 |

|

Somewhat important |

28.0 |

26.2 |

27.6 |

26.4 |

23.8 |

27.1 |

|

Not very important |

5.9 |

2.9 |

3.9 |

6.2 |

6.3 |

4.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A higher proportion of female than male Year 4 to Year 6 students answered that it is very important to them to be at school every day (70.9% compared to 66.1%), however, the difference was not statistically significant. No difference was measured between students in different geographic regions.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

Very important |

71.8 |

68.1 |

68.4 |

|

Somewhat important |

22.9 |

27.5 |

27.1 |

|

Not very important |

5.3 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A somewhat higher proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students said being at school every day is very important (71.8% compared to 68.1%), however, the difference was not statistically significant. This finding highlights that Aboriginal students have the same perceptions of the importance of regular attendance at school compared to non-Aboriginal students, however, this is not reflected in the attendance data for the cohort. Aboriginal students attend less often and less regularly than their non-Aboriginal peers and this suggests that there are barriers other than students’ views and perceptions that influence the attendance rates of Aboriginal students.

In the Commissioner’s 2015 consultation with Aboriginal children and young people, participants expressed not only a clear understanding of the connection between a good education and a good quality of life but also identified barriers to attendance such as family issues, transport or access difficulties and cultural differences.2 Additionally, in a 2010 Wellbeing Survey conducted on behalf of the Commissioner, Aboriginal children in remote areas spoke of the difficulties of attending school due to the loss of family members and attendance at funerals.3

Students in the 2019 Speaking Out Survey were asked how important it is to their parents or people who act as their parents that they go to school every day. A lower proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal students answered that it is very important to their parents (80.8% compared to 84.5%) and a significantly higher proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal students answered that it is not very important to their parents (4.8% compared to 1.7%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

Very important |

80.8 |

84.5 |

84.3 |

|

Somewhat important |

14.5 |

13.8 |

13.8 |

|

Not very important |

4.8 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

No significant difference was measured between male and female students and students in different geographic areas regarding their views on how important it is to their parents that they go to school every day.

Endnotes

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, “Listen To Us”: Using the views of WA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people to improve policy and service delivery, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Nexus Strategy Solutions, Sankey Associates and Fletcher J 2010, Research Report: Children and Young People’s Views on Wellbeing, for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 53.

Last updated May 2020

At 30 June 2019, there were 1,618 WA children in care aged between five and nine years, more than one-half of whom (55.1%) were Aboriginal.1

Children and young people in care often face significant barriers to educational attendance and attainment. However, educational participation and attainment are pivotal to their long-term outcomes.2

Standard 7 of the National Standards for out-of-home care is that children and young people up to at least 18 years are supported to be engaged in appropriate education, training and/or employment. There is, however, no data reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare as part of the National Standards Indicators.3

The Department of Education has provided attendance rates and levels for all compulsory aged WA children and young people in care. While this data is not directly comparable to the ACARA attendance data,4 in 2017 35.7 per cent of children and young people in care did not attend school more than 90 per cent of the available time.

|

Attendance rate |

Attendance level |

||||

|

90% or greater |

80% - <90% |

60% - <80% |

<60% |

||

|

2016 Semester 1 |

86.9 |

65.7 |

15.7 |

8.8 |

9.9 |

|

2017 Semester 1 |

87.4 |

64.3 |

17.0 |

9.8 |

8.9 |

Source: WA Department of Education administrative data provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Similarly, the Department of Communities Outcomes Framework for children in out-of-home care reported that in 2015–16 the attendance level (regularly attending) of WA children and young people in care at government schools was 67.1 per cent (58.8% for Aboriginal students and 76.1% for non-Aboriginal students).5 In other words, only around two-thirds of students in out-of-home-care attend for at least 90 per cent of the time. This is markedly lower than the attendance level for all students in government schools of 73.7 per cent in 2017.6

For further information on the attendance and achievement levels of children in care refer to:

Western Australian Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes framework for children in out-of-home care in Western Australia: 2015-2016 Baseline Indicator Report, Department for Child Protection and Family Support, Perth.

Tilbury C 2010, Educational status of children and young people in care, Children Australia, vol. 35, no. 4.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018–19, WA Government p. 26.

- Tilbury C 2010, Educational status of children and young people in care, Children Australia, Vol 35, No 4.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, National framework for protecting Australia's children indicators, AIHW [website].

- Data provided by the WA Department of Education to the Commissioner, noting the following: children in care are flagged in the Department’s administrative enrolment data, Semester 1 student attendance data is verified by school principals, and the attendance rate is the average half days attended as a percentage of available half days.

- Number of children at compulsory school age who have been in care for the entire reporting period and are regularly attending (90 per cent attendance) an education program, divided by the number of children at compulsory school age who have been in care for the entire reporting period, expressed as a percentage. Source: WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes framework for children in out-of-home care in Western Australia: 2015–2016 Baseline Indicator Report, WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2017, National Report on Schooling data portal, Student attendance rate by school sector and state/territory for Year 1-10 students.

Last updated May 2020

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018 data collection reports that approximately 30,200 WA children and young people (9.2%) aged five to 14 years have reported disability.1,2

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities states that people with disability should be guaranteed the right to inclusive education at all levels and that children with disability must not be excluded from free and compulsory primary education or secondary education.

WA students with disability commonly attend either special schools that enrol only students with special needs, special classes within a mainstream school or mainstream classes within a mainstream school (where students with disability might receive additional assistance).3

In 2018, almost all Australian school children aged five to 14 years with disability attended school (95.8%). Of these, nearly one third attended special classes or special schools (31.2%).4

The Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability provides a detailed snapshot of students receiving an adjustment for disability across Australia. This collection is still in the early stages of implementation and data cannot be compared across states, however, the data for WA shows that around one in five students received some level of adjustment to access education in 2018.

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

|

Support with Quality Differentiated |

7.0 |

8.9 |

9.2 |

|

Supplementary |

7.8 |

8.3 |

7.6 |

|

Substantial |

2.0 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

|

Extensive |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

All adjustments |

17.6 |

20.5 |

19.9 |

Source: ACARA, School Students with Disability

Notes: (Source: NCCD Selecting the level of adjustment)

1. Students with disability are supported through active monitoring and adjustments that are not greater than those used to meet the needs of diverse learners. These adjustments are provided through usual school processes, without drawing on additional resources.

2. Students with disability are provided with adjustments that are supplementary to the strategies and resources already available for all students within the school.

3. Students with disability who have more substantial support needs are provided with essential adjustments and considerable adult assistance.

4. Students with disability and very high support needs are provided with extensive targeted measures and sustained levels of intensive support. These adjustments are highly individualised, comprehensive and ongoing.

The data set is designed to collect information on the full range of students receiving adjustments to support their access and participation in learning because of disability, not just those who have a medical diagnosis. The data is collected by teachers using their professional judgements, based on evidence, to classify the adjustment levels.5

For an overview of school attendance for students with disability, refer to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare paper, Disability in Australia: changes over time in inclusion and participation in education.

Limited data exists on school attendance rates or levels for children with disability. It is therefore difficult to assess how WA children with disability are faring in relation to equal access to education.

More than 300 Year 7 to Year 12 students with disability who attend mainstream classes or programs participated in the Speaking Out Survey 2019. For more information refer to the School attendance indicator for the 12 to 17 years age group.

Endnotes

- The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions… In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities.’ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018, Western Australia, Table 1.1 Persons with disability, by age and sex, estimate, and Table 1.3 Persons with disability, by age and sex, proportion of persons.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2017, Disability in Australia: changes over time in inclusion and participation in education, Cat No DIS 69, AIHW.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, 4430.0 - Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018, Children with disability, ABS.

- Education Council, Nationally Consistent Collection of Data: School students with disability 2017, 2017 data on students in Australian schools receiving adjustments for disability.

Last updated May 2020

Student absences from school are influenced by a combination of home, school and individual factors. However, the relative importance of the various causes is contested. Parents and students tend to highlight school-related factors (for example, poor teaching and failure to engage students); while educators tend to stress parental attitudes and the home environment.1,2

Parents have an important role in encouraging their children to value and enjoy school and learning. There is strong evidence showing parental expectations and attitudes towards school significantly influence children’s experiences and outcomes.3 Parent participation in school activities, such as visiting their children’s class, attending assemblies and parent-teacher nights and volunteering, all provide a mechanism to allow parents to demonstrate their interest in their children’s education.

Families experiencing disadvantage and stress often struggle to engage in this manner, therefore additional services and programs can provide support.4 Research also suggests that ensuring parents are better informed about how poor attendance adversely impacts their children’s future wellbeing will also improve results.5

Improving the outcomes for disadvantaged students requires multiple approaches with shared responsibility between students, families, schools, communities and a range of government agencies.6

Reasons for Aboriginal children’s non-attendance are complex and can include the lack of recognition by schools of Aboriginal culture and history, the failure to fully recognise that Standard Australian English is not the first language of many Aboriginal students, particularly in remote areas, and the lack of quality engagement with families and communities.7

Schools have a significant role to play in improving attendance levels. A 2010 study found that there were very few high-quality evaluations of programs aimed at improving attendance, therefore evidence about what works is lacking.8 However, there are several indicators that highlight a child is having difficulty, some of which suggest the following for policy and practice:

- Focus early on children with a high level of unauthorised absences, which are more strongly associated with low achievement, than authorised absences.9

- Provide intensive and early assistance to students who are falling behind in literacy and numeracy so that poor attendees can make progress and those at risk of disengaging are supported.10

- Continue to develop policy and programs that take account of Aboriginal cultures and history, and develop expanded understandings of what it means to participate and engage in education.11

- Develop educational programs in collaboration with parents and community-based organisations.12

- For children with disability, good practice involves moving towards an inclusive education culture through policy and practice, including the development of appropriate support structures and funding regimes, and in-class changes including alternative curricula, individual planning and the use of technologies.13

Data gaps

Data reporting on the attendance rates and levels of children with disability is needed; without this, it is difficult to assess whether children with disability are being provided with consistent and equitable access to education and support and to allow for robust comparison between children with and without disability.

Data on attendance rates and levels of children and young people in out-of-home care and youth detention (Banksia Hill) should also be collected and publicly reported.

Endnotes

- Purdie N and Buckley S 2010, School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students, Issues Paper No 1 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Queensland Department of Education, Training and Employment 2013, Performance insights: School attendance, QLD Government.

- Department of Education, Fact Sheet: Parent engagement in learning, Australian Government.

- Hancock KJ and Zubrick SR 2015, Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school, prepared by Telethon Kids Institute for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Ibid.

- Purdie N and Buckley S 2010, School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students, Issues Paper No 1 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Ibid.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- The Smith Family 2018, Attendance lifts achievement: Building the evidence base to improve student outcomes, March 2018, The Smith Family.

- Purdie N and Buckley S 2010, School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students, Issues Paper No 1 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Ibid.

- The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) 2013, Inclusive Education for Students with Disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice, ARACY.

For more information on school attendance refer to the following resources:

- Cassells R et al 2017, Educate Australia Fair?: Education Inequality in Australia, Focus on the States Series, Issue No 5, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre.

- Hancock KJ et al 2013, Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts, Report for the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Hancock KJ and Zubrick SR 2015, Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school, report for Commissioner for Children and Young People, Telethon Kids Institute.

- Purdie N and Buckley S 2010, School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students, Issues Paper No 1 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Government.

- The Smith Family 2018, Attendance lifts achievement: Building the evidence base to improve student outcomes, The Smith Family.

- Zubrick SR et al 2006, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: Improving the Educational Experiences of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research.

For more information on children’s views on school, see Speaking out about School and Learning.