Safe in the community

Feeling safe in their neighbourhood and other communities or groups is essential for children’s healthy development. It provides them with the confidence to explore and learn about their environment outside of the family, engage in physical activity outside their home and build positive relationships with other adults and peers.1

When children feel unsafe this can result in developmental problems including difficulties forming positive and trusting relationships and mental health issues.2

Last updated August 2020

Limited data is available on whether WA young children aged 6 to 11 years feel safe, or are safe, in their community.

Overview

This indicator intends to collect data on whether WA children aged six to 11 years feel safe in their communities and how many WA children have experienced violence or abuse in their community, including negative online experiences.

Areas of concern

There is no data or research on the prevalence of WA children experiencing violence and abuse in their communities.

One-third (33.1%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported they feel safe in their local area all the time and 38.7 per cent reported they feel safe most of the time. One-quarter (25.9%) said they feel safe only sometimes or less.

In WA in 2018, 459 children aged 0 to nine years were recorded as victims of assault and 304 children were recorded as victims of sexual assault.

24.0 per cent of Australian children aged eight to 12 years have experienced unwanted contact and content online.

WA female children and young people aged 10 to 14 years are more than six times more likely than their male counterparts to be reported as victims of sexual assault.

Other measures

Injuries and poisoning are major causes of hospitalisation for children in Australia. A measure on child deaths or injuries has not been selected for the Indicators of wellbeing as data is regularly compiled by Kidsafe WA and the WA Ombudsman.

For information on child deaths refer to the Ombudsman’s annual Child Death Review. For information on injuries for children refer to Kidsafe WA Childhood Injury Bulletins & Reports.

Last updated August 2020

Communities have a significant influence on children’s lives. Safe and cohesive communities can improve children’s wellbeing and help them thrive.1,2

Healthy communities promote positive connections between families and children through social and recreational resources that improve social cohesion, encourage physical activity and build relationships between parents and children.3 If children do not feel safe in their communities this can lead to difficulties forming positive and trusting relationships, mental health issues and behavioural problems.4,5

How community is defined is not clear-cut; community often refers to the local neighbourhood, however, it can also include online communities, faith-based communities, sporting or activity-based communities and school communities. Adult perceptions of whether communities feel safe and supportive may not reflect those of the children in that community.6

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about feeling safe in their local area.

One-third (33.1%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported they feel safe in their local area all the time and 38.7 per cent reported they feel safe most of the time. One-quarter (25.9%) said they feel safe only sometimes or less.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

All the time |

36.0 |

30.6 |

32.0 |

34.5 |

40.7 |

33.1 |

|

Most of the time |

38.7 |

38.6 |

39.8 |

37.9 |

28.2 |

38.7 |

|

Sometimes |

15.5 |

18.1 |

17.3 |

14.6 |

19.5 |

17.0 |

|

A little bit of the time |

5.3 |

7.4 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

5.9 |

6.2 |

|

Never |

3.3 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

3.7 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

|

Prefer not to say |

1.2 |

3.2 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A higher proportion of male Year 4 to Year 6 students than female students felt safe in their local area all of the time or most of the time (74.7% compared to 69.2%). This difference was not statistically significant, although the gap between male and female students feeling safe all the time widens in high school (29.4% compared to 19.9%).

A higher proportion (40.7%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students in remote areas than non-remote areas felt safe in their local area all the time, although the differences were not statistically significant.

A significantly higher proportion of Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students than non-Aboriginal students felt safe in their local areas all the time (42.1% compared to 32.4%). Non-Aboriginal students were more likely than Aboriginal students to say they feel safe most of the time (39.5% compared to 28.2%). Largely equal proportions of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students feel safe only sometimes or less (25.7% compared to 25.8%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

All the time |

42.1 |

32.4 |

|

Most of the time |

28.2 |

39.5 |

|

Sometimes |

14.8 |

17.1 |

|

A little bit of the time |

6.0 |

6.2 |

|

Never |

4.9 |

2.5 |

|

Prefer not to say |

4.0 |

2.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Almost three-quarters of WA Year 4 to Year 6 students agree that their neighbours are friendly (74.2%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Agree |

72.6 |

76.9 |

76.2 |

66.5 |

71.7 |

74.2 |

|

I don't know |

19.5 |

18.7 |

17.9 |

26.1 |

21.5 |

19.5 |

|

Disagree |

8.0 |

4.4 |

5.9 |

7.4 |

6.7 |

6.2 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Students in the metropolitan area were most likely to report having friendly neighbours (76.2%) followed by students in remote (71.7%) and regional areas (66.5%). Students in regional areas were more likely than other students to say they don’t know if their neighbours were friendly.

There was no significant difference in the responses of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students to this question.

Between 2010 and 2013 the Children, Communities and Social Capital in Australia research project asked 108 children aged eight to 12 years about their communities.7 The research included four ‘disadvantaged’ communities, one community which was ‘average’ on most socioeconomic indicators and one community which was ‘advantaged’ on socioeconomic indicators.8

The participants were asked how they defined communities and from this the definition of a ‘social space within which people are personally connected and known to one another’ was developed.9

Most children in this study thought that caring, supportive relationships were the heart of communities. They highlighted good neighbours, family, get togethers, friends, time with parents, caring people and being listened to, as key aspects of a good community.10 Children who knew their neighbours and got on well with them described feeling safe and happy because they knew there were people looking out for them.11

A number of children in the study explained that other people in their community such as bus drivers and shop keepers also influenced their feeling of safety in their community. These adults could make children feel safe and welcome – or they sometimes made the children feel unwelcome and uncomfortable.12

In this study, children in some disadvantaged communities highlighted that they did not feel safe when their neighbours were swearing, drinking or behaving violently.13 In one community, the children reported that excessive use of alcohol by adults and violence associated with drunkenness were significant issues.14 Further, children highlighted that they felt unsafe when people drove cars in a dangerous manner. Speeding, doing burn-outs and doughnuts and road rage all made children feel very unsafe.15

A recent research project in Queensland conducted by the Queensland Family and Child Commission asked more than 7,000 children and young people aged between four and 18 years about their lives.16 This study also found that when children and young people witnessed adults and older teenagers drinking, fighting or taking drugs they felt unsafe.17

Institutions also form part of the community and the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (the Royal Commission) has highlighted that many institutions have failed to protect children.

The Royal Commission reported that children and young people are highly vulnerable to abuse perpetrated by a wide range of people associated with institutions, including staff, professionals, families, carers and other children. Furthermore, some children are more vulnerable than others, such as those with disability, those in residential settings and those who have previously been abused.

The Institute of Child Protection Studies was commissioned by the Royal Commission to develop an understanding of how children perceive safety and consider it within institutional contexts.18 An online survey was completed by 1,480 Australian children and young people aged 10 to 18 years.19 The following were key findings:20

- The most influential characteristic in determining how safe children felt within an institution was whether adults pay attention when a child or young person raised a concern or worry.

- If children and young people encounter an unsafe adult or peer they need another adult to believe them when they raised their concern and to step in and take control.

- The most significant barrier to seeking support at school was feeling uncomfortable talking to adults about sensitive issues.

Endnotes

- Child Family Community Australia and NAPCAN 2016, Stronger Communities, Safer Children: Findings from recent Australian research on the importance of community in keeping children safe, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Eastman C et al 2014, Thriving in Adversity: A positive deviance study of safe communities for children (SPRC Report 30/2014), Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kersten L et al 2017, Community Violence Exposure and Conduct Problems in Children and Adolescents with Conduct Disorder and Healthy Controls, frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience, Vol 11.

- Child Family Community Australia and NAPCAN 2016, Stronger Communities, Safer Children: Findings from recent Australian research on the importance of community in keeping children safe, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Bessell S and Mason J 2014, Putting the pieces in place: Children, communities and social capital in Australia, Australian National University and University of Western Sydney, p. 22.

- Bessell S and Mason J 2014, Putting the pieces in place: Children, communities and social capital in Australia, Australian National University and University of Western Sydney, p. 37-38.

- Bessell S 2016, Communities Matter: Children’s views on community in Australia, Australian National University, p. 10.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 19.

- Ibid, p. 20.

- Ibid, p. 26-27.

- Bessell S and Mason J 2014, Putting the pieces in place: Children, communities and social capital in Australia, Australian National University and University of Western Sydney, p. 39, 135.

- Bessell S 2016, Communities Matter: Children’s views on community in Australia, Australian National University, p. 26.

- The four to six-year olds participated through a teacher and librarian-led artwork activity. Source: Queensland Family and Child Commission 2018, This place I call home – The views of children and young people on growing up in Queensland, The State of Queensland, p. 11.

- Queensland Family and Child Commission 2018, This place I call home – The views of children and young people on growing up in Queensland, The State of Queensland, p. 33.

- Moore T et al 2016, Our safety counts: Children and young people’s perceptions of safety and institutional responses to their safety concerns, Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University.

- The survey was not designed to be representative, however, provides an indication of what children and young people need to feel safe in institutions.

- Moore T et al 2016, Our safety counts: Children and young people’s perceptions of safety and institutional responses to their safety concerns, Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, p. 8-9.

Last updated August 2020

This measure reports on negative online experiences and is included within this indicator recognising that children can increasingly access the internet and social media at any time and place.

The vast majority of Australian families have access to the internet, with 97.1 per cent of households with children under the age of 15 reporting having an internet connection at home.1

The Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey found that 92.7 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students have access to the internet at home. Furthermore, 43.0 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students spend time using the internet on a smartphone or computer every day or almost every day and 29.7 per cent use the internet on a smartphone or computer once or twice a week.2

In 2018, the Australian Communications and Media Authority conducted an online survey to explore how children and young people aged six to 13 years use mobile phones.3 For children aged 6 to 9 years, they found the most common uses for mobile phones was to play games (72.0%), to take photos and videos (58.0%), to use apps (51.0%). For children aged 10 to 11 years the most common uses were to play games (66.0%), to use apps (59.0%) and to take photos and videos (59.0%).4

In 2017, the eSafety Commissioner’s conducted the Digital Participation Survey with more than 3,000 young people in Australia aged 8 to 17 years and collected information on their online safety experiences and behaviours. In this survey the most common social media services used by children aged 8 to 12 years were YouTube (80.0%), Facebook (26.0%) and Snapchat (26.0%).5

Most children are more connected to technology than ever before and while this presents them with valuable opportunities for growth and development, it also makes children more vulnerable to having negative online experiences. Negative online experiences for this age group often include unwanted contact from strangers, exclusion from social groups and cyberbullying.

Negative online experiences are varied and can often, although not always, involve a form of cyberbullying. Cyberbullying has been defined as ‘an aggressive act involving the use of information and communication technologies to support deliberate, repeated and hostile behaviour by an individual or group which is intended to harm others’.6 Unwanted contact and exposure to viruses and fraud would generally not be classified as bullying, however, could be experienced as part of a bullying pattern.

Many researchers suggest that cyberbullying is a sub-set of traditional bullying rather than a new form on its own.7 However, there are some key differences. A unique feature of cyberbullying is the ability for the perpetrator to remain anonymous and to bully large numbers of people relatively effortlessly without a need to be physically close to them.8 For children and young people, cyberbullying can also be particularly fraught as it can happen when victims are alone, with less ability for teachers or parents to identify that it is occurring.

There is some evidence to suggest that children and young people can find it difficult to distinguish between harmless banter and bullying.9,10 This makes it more challenging for children experiencing bullying to report the behaviour and for those perpetrating bullying to understand where the line was crossed.

Negative online experiences including cyberbullying can significantly affect a child’s mental health and wellbeing.11,12,13 Cyberbullying can lead to significant mental health issues, including anxiety, stress and depression as well as substance abuse and in extreme cases, suicidal idealisation and actualisation.14,15 Australian research has found that mental health problems, including anxiety and depression, were more prevalent for children who reported that they had been cyberbullied compared to those who had been bullied offline.16

Children aged six to 11 years are less likely than older young people to have negative online experiences. At this age, most children do not have access to their own device and are more likely to be using technology while being at least partly supervised by a parent or carer. Research suggests that children younger than 10 years-old have a low risk of being bullied online or other negative experiences and that incidents of negative experiences escalates from 11 years of age.17

Nevertheless, children aged six to 11 years are increasingly online and can have negative experiences including cyberbullying.18 More research is needed on primary school-aged children’s online experiences.

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, 9.4 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported having been cyber-bullied by students from their school. This increased to 16.9 per cent for students in Year 7 to Year 12.19

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

50.0 |

44.2 |

47.2 |

44.2 |

49.6 |

46.9 |

|

Yes, bullied |

32.0 |

35.1 |

33.6 |

36.1 |

30.2 |

33.8 |

|

Yes, cyberbullied |

2.5 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

3.8 |

2.3 |

|

Both bullied and cyberbullied |

6.5 |

7.7 |

7.0 |

7.7 |

6.6 |

7.1 |

|

I don't know |

5.2 |

5.8 |

5.4 |

6.2 |

4.6 |

5.5 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.7 |

5.0 |

4.6 |

3.5 |

5.2 |

4.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences in responses between genders, geographic location or Aboriginal status in terms of cyberbullying.

International research suggests that some Aboriginal children and young people may engage with and experience social media in culturally specific ways including that culture may influence what counts as cyberbullying, and they may experience direct and indirect racism through social media which may or may not be identified as cyberbullying.20 More research is needed into Aboriginal children’s use and experiences of technology and social media.

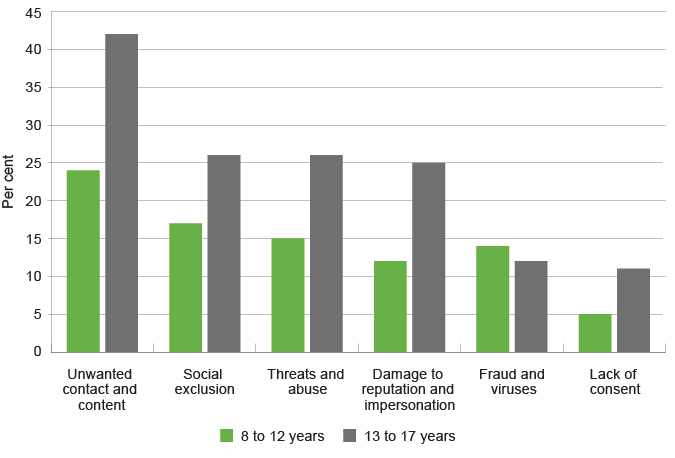

For more information on bullying at school more broadly refer to the A sense of belonging and supportive relationships at school indicator. In 2017, the eSafety Commissioner conducted research with Australian children and young people about their online experiences. The survey comprised a random sample of approximately 3,000 children and young people aged eight to 17 years collected over a 12-month period to June 2017.21 Results were disaggregated into two age groups, eight to 12 years and 13 to 17 years.22

This study found that a relatively high proportion of children aged eight to 12 years are exposed to a wide range of negative online experiences.23

|

Male |

Female |

|

|

Unwanted contact and content |

30.0 |

35.0 |

|

Social exclusion |

19.0 |

24.0 |

|

Threats and abuse |

19.0 |

22.0 |

|

Damage to reputation and impersonation* |

17.0 |

20.0 |

|

Fraud and viruses |

16.0 |

11.0 |

|

Lack of consent** |

8.0 |

8.0 |

Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers

* Damage to reputation and impersonation including having lies and rumours spread about them or having inappropriate photographs posted of themselves without their consent

** Lack of consent included having personal information accessed or posted without agreement.

Proportion of children and young people having negative online experiences by category and age, per cent, Australia, 2017

Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers

Unwanted contact and content was the most common experience, with 24.0 per cent of Australian children aged eight to 12 years experiencing this. Social exclusion was the second most common experience (17.0%).

While proportions were relatively high for both male and female respondents, the survey found some differences between genders.

|

Male |

Female |

|

|

Unwanted contact and content |

30.0 |

35.0 |

|

Social exclusion |

19.0 |

24.0 |

|

Threats and abuse |

19.0 |

22.0 |

|

Damage to reputation and impersonation |

17.0 |

20.0 |

|

Fraud and viruses |

16.0 |

11.0 |

|

Lack of consent |

8.0 |

8.0 |

Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers

Female users were more likely to report all types of negative experiences with the exception of fraud and viruses. Unwanted contact and content was the most common experience for both genders followed by social exclusion (unwanted contact and content: 35.0% female compared to 30.0% male, social exclusion: 24.0% female compared to 19.0% male).

Measuring the prevalence of cyberbullying is challenging as different definitions and methodologies limit the ability to compare cohorts and determine trends over time.24

A 2014 research synthesis by the Social Policy Research Centre estimated that approximately 20.0 per cent of eight to 17 year-olds in Australia have been cyberbullied (around 463,000 young people) and that the majority of victims are in the 10 to 15 year age group (around 365,000 young people). The authors note that the estimates could range from 100,000 less to around 200,000 more, depending on the definition of cyberbullying and other assumptions made when extrapolating from survey samples.25

Recent research also used the results of multiple bullying studies to conclude that cyber-bullying in Australia is less common than traditional bullying with approximately seven per cent of children and young people reporting experiences of cyberbullying and 3.5 per cent having perpetrated cyberbullying.26

Evidence also suggests that there is an overlap between the children and young people who experience physical bullying and cyberbullying, and those who perpetrate physical bullying and cyberbullying.27

Children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, LGBTI children and children with disability are more at risk of having negative online experiences.28,29 These groups will be discussed in more detail in the Safe in the community indicator for the 12 to 17 years age group.

Response to and impact of negative online experiences

Negative online experiences affect children and young people in a range of ways. In the eSafety Commissioner’s survey, almost two-thirds (63.0%) of respondents aged eight to 17 year reflected negatively on what happened to them. Survey participants noted that they did not feel good about themselves, felt left out and lost some of their friends. Children were less likely to reflect negatively than young people (55.0% of 8 to 12 year-olds compared to 69.0% of 13 to 17 year-olds).30

To cope with these experiences, children and young people undertook a range of actions. The majority of eight to 17 year-olds (71.0%) sought help through informal networks, telling their parents, family and friends. Just over half (51.0%) employed their own self-help strategies, for example changing passwords, closing social media accounts, confronting the bully or researching solutions online. A smaller proportion (24.0%) utilised formal avenues, reporting the incident to the police, their school or the social media company. These results are not broken down further by age.31

In dealing with these experiences, many children and young people also reported gaining positive outcomes from having negative online experiences, with 65.0 per cent of eight to 17 year-olds being able to able to interpret what had happened in a positive way. This included becoming more aware of online risks (40.0%), knowing who their ‘real’ friends were (33.0%), learning to use the internet in a more balanced way (23.0%) and developing a greater understanding of their online behaviour (19.0%).32

Children were less likely than teenagers to be able to interpret their negative experience in a positive way (58.0% of 8 to 12 year-olds compared to 70.0% of 13 to 17 year-olds).33

Parents’ concerns and responses

Parents play a significant role in ensuring their children are safe online and in supporting positive online behaviours; mitigating risk, providing guidance and advice and ‘policing’ internet use. Parents’ role is particularly important for children aged six to 11 years, as they have a high level of control over their child’s access to the internet and this age group is when children begin to learn safe online behaviours.

In research undertaken by the eSafety Commissioner in 2018, 3,250 Australian parents of children aged two to 17 years shared their views about parenting in the digital age.34 The top four concerns of parents of children and young people aged six to 17 years were:35

- Contact with strangers (40.0%)

- Exposure to inappropriate content (other than pornography) (37.0%)

- Being bullied online (37.0%)

- Accessing/being exposed to pornography (37.0%).

The most common way for parents to find out about their child’s negative online experiences was being told by them (59.0%), highlighting the importance of having a good parent-child relationship.36

Overall, the majority of parents (62.0%) in this study dealt with these concerns themselves, by taking proactive measures including educating their child on how to deal with negative situations, increasing monitoring or requesting that the child block or unfriend the person responsible.37 Parents responded differently depending on the age of their child.

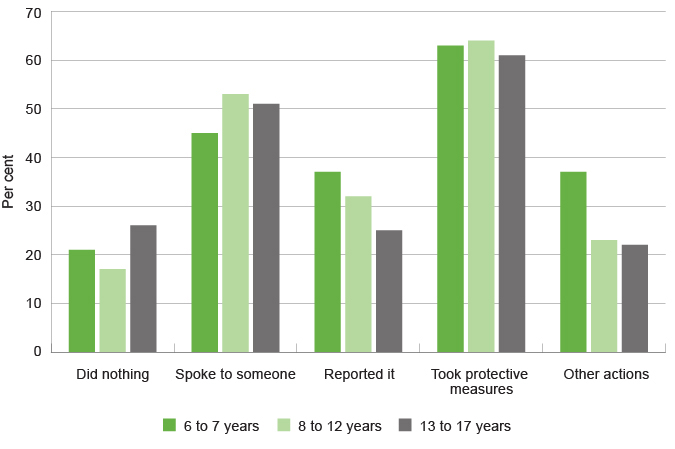

|

6 to 7 years |

8 to 12 years |

12 to 17 years |

|

|

Did nothing |

21.0 |

17.0 |

26.0 |

|

Spoke to someone |

45.0 |

53.0 |

51.0 |

|

Reported it |

37.0 |

32.0 |

25.0 |

|

Took protective measures |

63.0 |

64.0 |

61.0 |

|

Other actions* |

37.0 |

23.0 |

22.0 |

Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018, Parenting in the digital age

Note: Parents were able to select more than one response.

How parents dealt with their child’s negative online experience by age of child, per cent, Australia, 2018

Source: Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018, Parenting in the digital age

Similar proportions of parents across all age groups took protective measures and spoke to someone, while parents of older children were less likely to report negative experiences and more likely to do nothing.

The survey results also showed that in terms of responding to disclosures, parents of daughters aged eight to 12 years were more likely than parents of sons to report the negative behaviour and take protective measures.38

While parents are clearly concerned about online safety, they do not appear to be proactive in seeking out online safety information preceding a negative online experience, with only 36.0 per cent searching for or receiving online safety information.39

A Victorian survey40 conducted in 2017 with 2,600 parents found that respondent parents had a range of strategies to monitor and control their child’s online use which varied with age.

|

6 to 12 years |

13 to 18 years |

|

|

I established ground rules* |

91.0 |

80.9 |

|

I limit time use* |

85.6 |

52.8 |

|

I talk about safe use of internet connected devices* |

82.8 |

86.5 |

|

I supervise use* |

79.9 |

40.7 |

|

I monitor online activity* |

74.3 |

48.1 |

|

I use child safety software and locks* |

48.3 |

22.1 |

|

Something else* |

13.6 |

14.0 |

|

I do not monitor my child’s use of devices* |

7.8 |

22.1 |

|

Not relevant to my child (too young)* |

5.6 |

1.4 |

|

Child is not allowed to use electronic devices at all* |

0.6 |

1.0 |

Source: Parenting Resource Centre, Parenting Today in Victoria Technical Report

* Statistically significant difference across age groups, p<.001.

Parents of children aged six to 12 years were most likely to talk about establishing ground rules (91.0%) and limiting time use (85.6%). However, only 48.3 per cent of parents reported using child safety software and locks. Parents’ strategies change as children age.

No data is available on WA parents’ experiences or opinions about their children’s online activities.

Endnotes

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2018, 8146.0 - Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016-17, ABS.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Australian Communications and Media Authority 2019, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones, Australian Communications and Media Authority [online].

- Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers, Office of the eSafety Commissioner, p. 8.

- Jadambaa A et al 2019, Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 53, No 9.

- Kowalski R and Limber S 2013, Psychological, Physical, and Academic Correlates of Cyberbullying and Traditional Bullying, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol 53, No 1.

- Jadambaa A et al 2019, Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 53, No 9.

- Hemphill S et al 2015, Predictors of Traditional and Cyber-Bullying Victimization: A Longitudinal Study of Australian Secondary School Students, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol 30, No 15.

- Jeffrey J and Stuart J 2019, Do Research Definitions of Bullying Capture the Experiences and Understandings of Young People? A Qualitative Investigation into the Characteristics of Bullying Behaviour, International Journal of Bullying Prevention, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00026-6 [online].

- Whittle J et al 2019, ‘There’s a Bit of Banter’: How Male Teenagers ‘Do Boy’ on Social Networking Sites, in Lumsden K and Harmer E (eds) Online Othering, Palgrave Studies in Cybercrime and Cybersecurity. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Wu Y et al 2016, A Systematic Review of Recent Research on Adolescent Social Connectedness and Mental Health with Internet Technology Use, Adolescent Research Review, Vol 1, No 2

- Tandoc E et al 2015, Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing?, Science Direct, Vol 43 p 139-146.

- Child Family Community Australia 2012, Parental involvement in preventing and responding to cyberbullying, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government.

- O'Keeffe GS et al 2011, Clinical report: The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families, Pediatrics, Vol 127, No 4, p. 801.

- Carlson B and Frazer R 2018, Cyberbullying and Indigenous Australians: A Review of the Literature, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales and Macquarie University, Sydney.

- Child Family Community Australia 2012, Parental involvement in preventing and responding to cyberbullying, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government.

- Katz I et al 2014, Research on youth exposure to, and management of, cyberbullying incidents in Australia: Synthesis report (SPRC Report 16/2014), Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia, p. 2.

- Monks C et al 2012, The emergence of cyberbullying: A survey of primary school pupils’ perceptions and experiences, School Psychology International, Vol 33, No 5.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Carlson B and Frazer R 2018, Cyberbullying and Indigenous Australians: A Review of the Literature, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales and Macquarie University, Sydney, p. 12-13.

- Office of the ESafety Commissioner 2018, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers, Australian Government, p. 3.

- This is because major social media sites (e.g. Facebook, Instagram and YouTube) specify that users must be at least 13 years-old. Source: Child Family Community Australia 2018, Online Safety: CFCA Resource Sheet, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Office of the ESafety Commissioner 2018, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers, Australian Government, p. 21.

- Jadambaa A et al 2019, Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 53, No 9.

- Katz I et al 2014, Research on youth exposure to, and management of, cyberbullying incidents in Australia: Synthesis report (SPRC Report 16/2014), Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia, p. 2.

- Jadambaa A et al 2019, Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 53, No 9.

- Katz I et al 2014, Research on youth exposure to, and management of, cyberbullying incidents in Australia: Synthesis report (SPRC Report 16/2014), Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Australia, p. 3.

- Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers, Australian Government, p. 13-14.

- Abreu R and Kenny M 2018, Cyberbullying and LGBTQ Youth: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for Prevention and Intervention, Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, Vol 11, No 1.

- Office of the ESafety Commissioner 2018, State of Play – Youth, Kids and Digital Dangers, Australian Government, p. 23.

- Ibid, p. 24.

- Ibid, p. 23.

- Ibid, p. 23.

- Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2018, Parenting in the digital age, Australian Government, p. 2.

- Ibid, p. 6.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Ibid, p. 18.

- Ibid, p. 20

- Ibid, p. 21

- Parenting Research Centre (PRC) 2017, Parenting Today in Victoria: Report of Key Findings (report produced for the Department of Education and Training, Victoria), PRC.

Last updated August 2020

Children aged six to 11 years have a low risk of physical (or sexual) harm from individuals outside of the home,1 however, children who are exposed to violence in their community are at higher risk of negative long-term outcomes including substance abuse, anxiety-related disorders and exhibiting future violent behaviour.2,3

Exposure to violence in the community can also contribute to problems forming positive and trusting relationships and is strongly associated with children exhibiting conduct problems.4

Community violence generally refers to violence in the community that is not perpetrated by a family member and is intended to cause harm.5

For children aged six to 11 years, exposure to violence in the community may be observing or experiencing bullying or aggression from adults or peers or less commonly physical (and sexual) assault.

This measure ideally reports on experiences of physical and sexual assault outside of the family and the home (which is discussed in the Safe in the home indicator); however, available data does not always distinguish between violence in the community and family and domestic violence.

There is limited data on children aged six to 11 years experiencing violence in the community (as distinct from family and domestic violence).

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing. In this survey Year 9 to Year 12 students were asked about their experiences of being hit or physically harmed, for these results refer to the Safe in the community indicator for age group 12 to 17 years.

The ABS collects data on victims of assault and sexual assault in the Recorded Crimes – Victims publication from administrative systems maintained by police agencies within each state and territory. This collection includes data on assault and sexual assault for children and young people, however, does not always distinguish between crime in the community and family and domestic violence.

In 2019, 62.5 per cent of physical assaults and 27.3 per cent of sexual assaults recorded in WA were family and domestic violence-related.6

For more information on family and domestic violence refer to the Safe in the home indicator.

It should be noted that the following statistics are based on crimes recorded by WA Police and therefore will underestimate the prevalence of assault.7,8

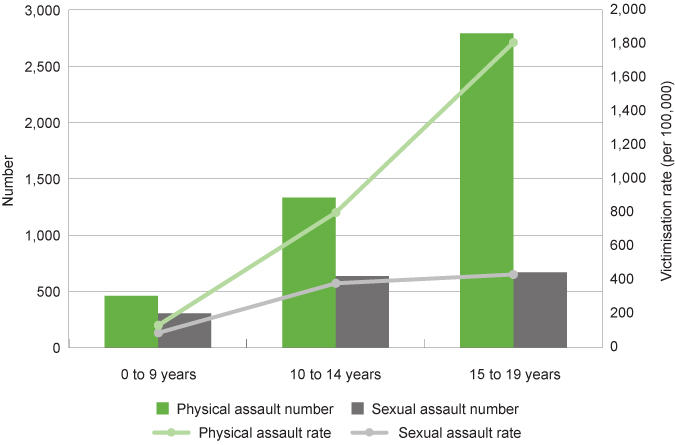

In WA in 2019, 459 children aged 0 to nine years and 1,332 10 to 14 year-olds were recorded as victims of physical assault and 304 children aged 0 to nine years and 634 children aged 10 to 14 years were recorded as victims of sexual assault.9

|

Physical assault |

Sexual assault |

|||

|

Number |

Number per 100,000 |

Number |

Number per 100,000 |

|

|

0 to 9 years |

459 |

132.8 |

304.0 |

87.9 |

|

10 to 14 years |

1,332 |

801.8 |

634.0 |

381.6 |

|

15 to 19 years |

2,792 |

1,809.9 |

669.0 |

433.7 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019

WA children and young people recorded as victims of physical assault and sexual assault by age, number and rate, WA, 2019

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019

The risk of physical assault increases significantly as children age.

There is no data publicly available on the location of these offences for these age groups. However, for the total population (including adults), 63.4 per cent of physical assaults and 71.9 per cent of sexual assaults occurred in a residential location.10

Furthermore, evidence shows that young children are most likely to be physically (or sexually) abused by parents and/or caregivers and other relatives.11

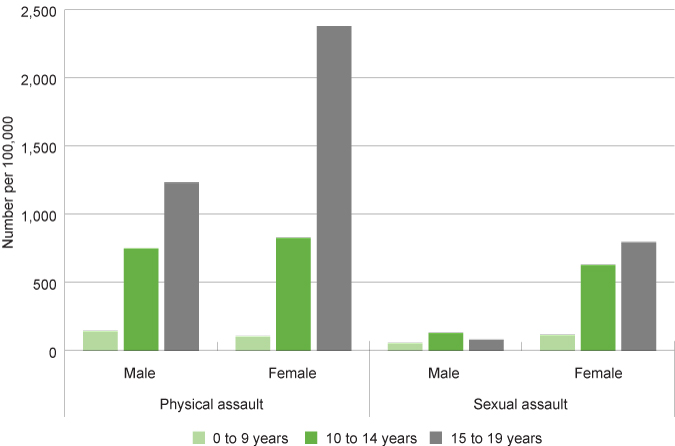

There are significant differences between male and female young people’s experiences of violence with female children and young people being significantly more likely to be the victims of physical and sexual assault across all age groups, except physical assault of 0 to nine year-old children.

Notably, WA female children and young people aged 10 to 14 years are five times more likely than WA male children and young people in that age group to be reported as victims of sexual assault.

|

Assault |

Sexual assault |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

0 to 9 years |

255 |

178 |

98 |

195 |

|

10 to 14 years |

639 |

670 |

112 |

510 |

|

15 to 19 years |

973 |

1,794 |

64 |

600 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019

|

Assault |

Sexual assault |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

0 to 9 years |

143.8 |

105.7 |

55.3 |

115.8 |

|

10 to 14 years |

750.9 |

826.8 |

131.6 |

629.4 |

|

15 to 19 years |

1,233.4 |

2,380.0 |

81.1 |

796.0 |

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019

Children and young people recorded as victims of physical assault and sexual assault by age group and gender, number per 100,000, WA, 2019

Source: ABS, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019

The Australian Bureau of Statistics collection on Recorded Crime – Victims does not report on data for Aboriginal people in WA as the data is not of sufficient quality.12 Furthermore, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) does not provide data on children and young people’s experiences of violence.13

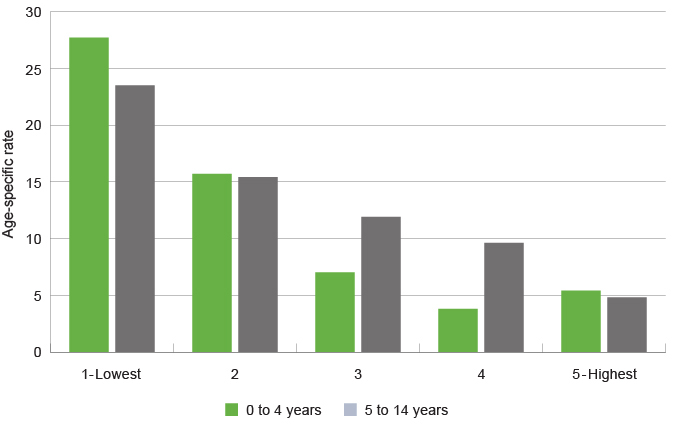

Children and young people from the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas are five times more likely to be hospitalised due to assault than other children and young people.14

|

1 - Lowest |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 - Highest |

||

|

0 to 4 years |

Number |

91 |

48 |

22 |

12 |

16 |

|

Rate |

27.7 |

15.7 |

7.0 |

3.8 |

5.4 |

|

|

5 to 14 years |

Number |

142 |

88 |

70 |

56 |

30 |

|

Rate |

23.5 |

15.4 |

11.9 |

9.6 |

4.8 |

|

Source: AIHW, Hospitalised injury and socioeconomic influence in Australia 2015–16

Notes:

1. Only a small proportion of injuries result in admission to a hospital.

2. Rates are directly age-standardised (per 100,000) using populations by socioeconomic status groups, which do not include persons in areas for which the socioeconomic status could not be determined.

Hospitalised assault injury cases by socioeconomic status and age group, age-specific rate (per 100,000), Australia, 2015–16

Higher rates of injury in communities with low socioeconomic status are related to the social determinants of health which increase risk factors for people living with disadvantage. Children and young people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage are more likely to be living in communities where there are higher levels of unemployment, families experiencing poverty or financial stress, poor housing conditions and a lack of access to services.15

Children are also at risk of abuse, particularly sexual abuse, within institutions. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (the Royal Commission) found that a large number of children have been sexually abused in many Australian institutions. The Royal Commission highlighted that sexual abuse of children has occurred in almost every type of institution where children reside or attend for educational, recreational, sporting, religious or cultural activities.

It should be noted that while the Royal Commission was unable to determine the prevalence of child sexual abuse, survivors reported their age when the abuse started to the Royal Commission. For most victims (51.1%) the sexual abuse started when they were aged between 10 and 14 years. For almost one-third of victims (31.1%) the abuse started when they were younger (aged 5 to 9 years).16

There is no data on the prevalence of child abuse, including sexual abuse, in institutional settings in WA.17 It is expected that this will be at least partially addressed by the Australian Child Maltreatment Study funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Endnotes

- Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) 2014, CFCA Resource Sheet: Who abuses children?, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Guerra NG and Dierkhising MA 2011, The Effects of Community Violence on Child Development, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development.

- Luthar S and Goldstein A 2015, Children’s Exposure to Community Violence: Implications for Understanding Risk and Resilience, Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology, Vol 33, No 3.

- Kersten L et al 2017, Community Violence Exposure and Conduct Problems in Children and Adolescents with Conduct Disorder and Healthy Controls, frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience, Vol 11.

- Guerra NG and Dierkhising MA 2011, The Effects of Community Violence on Child Development, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018, Table 22 Victims of family and domestic violence-related offences by sex, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013, Defining the Data Challenge for Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence, ABS.

- Australian Law Reform Commission 2010, The prevalence of sexual violence, Australian Government [website].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 7 Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2019, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 8 Victims, Location where offence occurred by selected offences, States and territories, 2019.

- Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) 2014, CFCA Resource Sheet: Who abuses children?, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019 Explanatory Notes, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, 4714.0 - National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014-15, ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and Pointer SC 2019, Hospitalised injury and socioeconomic influence in Australia, 2015–16, Injury research and statistics series No 125, Cat No INJCAT 205, AIHW.

- American Psychological Association 2019, Fact sheet: violence and socioeconomic status, American Psychological Association.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017, Final Report: Nature and Cause, Australian Government, p. 87.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017, Nature and cause: summary, Australian Government [website].

Last updated December 2019

At 30 June 2019, there were 1,618 WA children in care aged between five and nine years, more than one-half of whom (55.1%) were Aboriginal.1

In 2017, CREATE Foundation collected data from Australian children and young people aged 10 to 17 years about their lives in the care system.2 Only 31.4 per cent of respondents indicated they had a sense of connection with the community in which they live.3 There is no other information on this measure.

There is no data or information publicly available on whether WA children in care aged six to 11 years feel safe in the community that they live in.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018-19, WA Government p. 26.

- CREATE Foundation have noted in their 2018 report that recruitment of participants was difficult and resulted in a non-random sample. McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 17-19.

- McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 9.

Last updated August 2020

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018 data collection reports that approximately 30,200 WA children and young people (9.2%) aged five to 14 years have reported disability.1,2

Children with disability are at greater risk of not feeling safe in their community and experiencing violence and abuse.3,4,5

There are no nationally consistent data sets available to determine the extent of violence, abuse and neglect of children with disability.6

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.7 The survey included young people in Year 7 to Year 12 with disability. For responses from these students regarding their safety in the community refer to the Safe in the community indicator for 12 to 17 years.

Research was commissioned by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (the Royal Commission) to develop an understanding what helps children and young people with disability and high support needs to feel and be safe in institutional settings. This was a small study with 22 children and young people aged between seven and 25 years.8

This research found that children and young people with disability were vulnerable because institutional practices often isolated them from their local communities and long-term support relationships.9 The study also suggested that children and young people with disability can have a diminished social life as they find it difficult to assess the relative risk of harm and can fear people they do not know, as ‘stranger danger’ is emphasised by parents and caregivers.10

The Royal Commission also concluded that children with disability who disclosed sexual abuse were often not believed or their distress was explained as a function of their disability. Furthermore, survivors with communication and cognitive impairments were reliant on supportive adults noticing and understanding changes in their behaviour after the abuse.11

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability has been established to specifically address evidence that people with disability are being abused in institutional and other settings. This Royal Commission is currently receiving submissions and holding hearings.

Endnotes

- The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions… In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities.’ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018, Western Australia, Table 1.1 Persons with disability, by age and sex, estimate, and Table 1.3 Persons with disability, by age and sex, proportion of persons.

- Wayland S and Hindmarsh G 2017, Understanding safeguarding practices for children with disability when engaging with organisations, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 3.

- Robinson S 2016, Feeling safe, being safe: what is important to children and young people with disability and high support needs about safety in institutional settings?, Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University, p. 9.

- Jones L et al 2012, Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, The Lancet, Vol 380, No 9845.

- Community Affairs References Committee 2015, Violence, abuse and neglect against people with disability in institutional and residential settings, including the gender and age related dimensions, and the particular situation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, and culturally and linguistically diverse people with disability, Commonwealth of Australia, p. 37.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Robinson S 2016, Feeling safe, being safe: what is important to children and young people with disability and high support needs about safety in institutional settings?, Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017, Final Report: Preface and executive summary, Australian Government, p. 14.

Last updated August 2020

Children who feel safe in the community they live in are more likely to have the confidence to explore and develop their independence, healthy relationships with other adults and feel able to speak up if they ever feel unsafe.

The right to play and enjoy community life in places and spaces that are safe and welcoming is something all children are entitled to under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).1

Safe places and spaces in the community also help children to develop their creativity and imagination and have the confidence to lead healthy, active lifestyles as they grow older.2 Feeling safe in the community increases the likelihood that children will be happy to engage in active play in their neighbourhood which encourages healthy behaviours into the future. This reduces their risk of obesity and other health issues during childhood and into adulthood.

For more information on play and physical health refer to the Physical health indicator for the six to 11 years age group.

Children who are exposed to violence or abuse in their community either as victims or onlookers can experience multiple negative outcomes including problems forming relationships, anxiety-related disorders and behavioural issues.3,4,5

Local communities can play a significant role in supporting vulnerable children, particularly where services are not meeting their needs. Building respectful, trusting relationships with vulnerable children has a powerful impact and can be the circuit breaker that disrupts their trajectory of vulnerability and creates a pathway for positive change.6

Creating safe neighbourhoods and communities for children aged six to 11 years requires a number of areas of focus:

- Ensuring public spaces such as parks, footpaths and playgrounds are safe for children and provide them with opportunities to explore, learn, engage in active play and interact with other children and adults in the neighbourhood.

- Ensuring organisations that interact with children, including schools, sports/activity groups, privately run play-centres and council facilities, employ child safe policies and practices.

- Implementing policies which are focused on reducing disadvantage and social exclusion more broadly, which can indirectly reduce crime and antisocial behaviour in socially and economically disadvantaged communities.7,8

Safe, accessible places are an important component of healthy communities and have an impact on community cohesion and how a community works together, shares values and overcomes adversity. Ensuring public spaces are safe and responsive to the local community’s needs is critical. This includes asking children what would make the public spaces in their community more safe and welcoming for them.

Communities where there are low incomes, high unemployment and limited access to services, are more likely to have higher levels of crime and antisocial behaviour.9 Poverty does not cause criminal behaviour, however, the experience of being poor creates material and social conditions (high levels of stress, mental health issues, lack of access to services etc.) that increase the likelihood of being a victim or perpetrator of criminal behaviour.10

A law and order response which criminalises adults (who are often parents) and some children and young people does not lead to long term change for that community.11,12 Policies which support communities to address identified issues should be place-based and designed by the people, including children, in that community so they are tailored to local circumstances and the community’s needs.13,14

Furthermore, policies which address poverty and disadvantage more broadly are essential to improve affected children’s experiences of feeling and being safe in their community.

Online safety is also important for children aged six to 11 years. Educating children about online safety is critically important, as without appropriate support and guidance, negative experiences can significantly affect a child’s mental health and wellbeing.15,16,17 There are a number of online resources which help families and communities create safer on-line environments including the National Centre Against Bullying website and the eSafety Commissioner website.

Children are also vulnerable to abuse when organisations neglect their responsibilities to foster a child-safe environment. This can be through failing to listen to children or due to a lack of policies and procedures aimed at reducing the risk of harm and prioritising the reputation of the organisation over the wellbeing of children.

Organisations that interact with children, either as part of their normal operations or on an ad-hoc basis, need to engage in child safe work practices. The Commissioner for Children and Young People WA publishes the National Principles for Child Safe Organisations WA: Guidelines and other child safe resources to assist organisations to identify and manage risks that affect the safety and wellbeing of children.

Studies have repeatedly shown that when children have no confidence that adults or institutions will respond to their safety concerns, they are less likely to raise concerns or seek help.18 Child safe and friendly organisations establish mechanisms for listening to children and young people about all types of concerns or complaints. A child-friendly complaint system must provide children with a variety of safe ways to share concerns; respond appropriately to any complaints, disclosures or suspicions of harm; and review all complaints from children and achieve systemic improvements.

For more information on developing a child-friendly complaints system refer to the Commissioner for Children and Young People’s Complaints resources page.

Data gaps

There is limited data on WA children’s experiences of their communities including whether they feel safe and welcome. It is important to gather children’s perspectives of their communities and what makes them feel safe. Children’s perceptions of safety are important and influence their behaviours, attitudes and mental health.

There is limited data on the prevalence of WA children’s experiences of violence and abuse in their communities.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse highlighted a lack of comprehensive data on abuse of children and young people in institutions and recommended that the Australian Government conduct and publish a nationally representative prevalence study on a regular basis to establish the extent of child maltreatment in institutional and non-institutional contexts in Australia (Recommendation 2.1).19 It is expected that this gap will be at least partially addressed by the Australian Child Maltreatment Study funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Endnotes

- UNICEF 2019, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, UNICEF [website].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2019, Discussion Paper: Living Environment - The effects of physical and social environments on the health and wellbeing of children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Guerra NG and Dierkhising MA 2011, The Effects of Community Violence on Child Development, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development.

- Luthar S and Goldstein A 2015, Children’s Exposure to Community Violence: Implications for Understanding Risk and Resilience, Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology, Vol 33, No 3.

- Kersten L et al 2017, Community Violence Exposure and Conduct Problems in Children and Adolescents with Conduct Disorder and Healthy Controls, frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience, Vol 11.

- Little M et al 2015, Bringing Everything I Am Into One Place, Dartington Social Research Unit and Lankelly Chase.

- Webster C and Kingston S 2014, Crime and Poverty, in Reducing Poverty in the UK: A collection of evidence review, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, p. 148.

- Schwartz M 2010, Building communities, not prisons: Justice reinvestment and Indigenous over-imprisonment, Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 14, No 1.

- American Psychological Association 2019, Fact sheet: violence and socioeconomic status, American Psychological Association.

- Webster C and Kingston S 2014, Crime and Poverty, in Reducing Poverty in the UK: A collection of evidence review, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, p. 149.

- Schwartz M 2010, Building communities, not prisons: Justice reinvestment and Indigenous over-imprisonment, Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 14, No 1.

- Walsh, Tamara 2018, Keeping vulnerable offenders out of the courts: lessons from the United Kingdom, Criminal Law Journal, Vol 42, No 3.

- Bellefontaine T and Wisener R 2011, The evaluation of place-based approaches: Questions for further research, Policy Horizons Canada, p 6.

- Schwartz M 2010, Building communities, not prisons: Justice reinvestment and Indigenous over-imprisonment, Australian Indigenous Law Review, Vol 14, No 1.

- Tandoc E et al 2015, Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing?, Science Direct, Vol 43 p 139-146.

- Wu Y et al 2016, A Systematic Review of Recent Research on Adolescent Social Connectedness and Mental Health with Internet Technology Use, Adolescent Research Review, Vol 1, No 2.

- Child Family Community Australia 2012, Parental involvement in preventing and responding to cyberbullying, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government.

- Moore T et al 2016, Our safety counts: Children and young people’s perceptions of safety and institutional responses to their safety concerns, Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, p. 7.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2017, Final Report: Preface and executive summary, Australian Government, p. 106.

For more information on the importance of children feeling and being safe in their community refer to the following resources:

- Bessell S and Mason J 2014, Putting the pieces in place: Children, communities and social capital in Australia, Australian National University and University of Western Sydney.

- Child Family Community Australia and NAPCAN 2016, Stronger Communities, Safer Children: Findings from recent Australian research on the importance of community in keeping children safe, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2019, Discussion Paper: Living Environment - The effects of physical and social environments on the health and wellbeing of children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Robinson S 2016, Feeling safe, being safe: what is important to children and young people with disability and high support needs about safety in institutional settings?, Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University.

Endnotes

- Tucci J et al 2008, Children’s sense of safety: Children’s experiences of childhood in contemporary Australia, Australian Childhood Foundation, p. 11.

- Guerra NG and Dierkhising MA 2011, The Effects of Community Violence on Child Development, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018, Table 7 - Victims, Age by selected offences and sex, States and territories, 2018, ABS.