Physical health

Physical health is a basic building block for children’s current wellbeing and future life outcomes. Being physically healthy includes being physically active, having a good diet and being in the healthy weight range.

Children aged 6 to 11 years are in a critical phase for establishing positive health behaviours to support wellbeing outcomes over their lifetime.

Last updated August 2021

Some data is available on whether WA children aged 6 to 11 years are physically healthy.

Overview

This indicator considers key measures of physical health for children including physical activity, screen time, diet, weight and long-term health issues.

Physical health is influenced by a range of factors including genetic, social and environmental influences. Research has found that Australian children living in areas with a high risk of social exclusion1 have, on average, worse health outcomes than children living in other areas.2 In particular, socioeconomic indicators such as having higher income and education levels are linked to better health outcomes.3

In the Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey, nearly two-thirds of Year 4 to Year 6 students rated their health as excellent or very good (26.8% excellent and 36.9% very good), and another 28.7 per cent rated their health as good.

While less than half of WA children aged five to nine years were assessed by their parent/carer as meeting the recommended level of physical activity in 2019, the proportion of children that parents/carers reported as meeting the recommendation continued to increase from 37.6 per cent in 2015 to 48.0 per cent in 2019.

There is limited recent data, however the available data suggests that Aboriginal children are more physically active than non-Aboriginal children in WA.

Areas of concern

In 2019 the proportion of WA children aged nine to 15 years eating sufficient vegetables remains very low at 7.6 per cent, however this is a modest increase from 4.1 per cent in 2017.

Only 32.3 per cent of WA female children and young people aged 5 to 15 years were reported as meeting the physical activity guidelines, compared to 45.2 per cent of male WA children and young people.

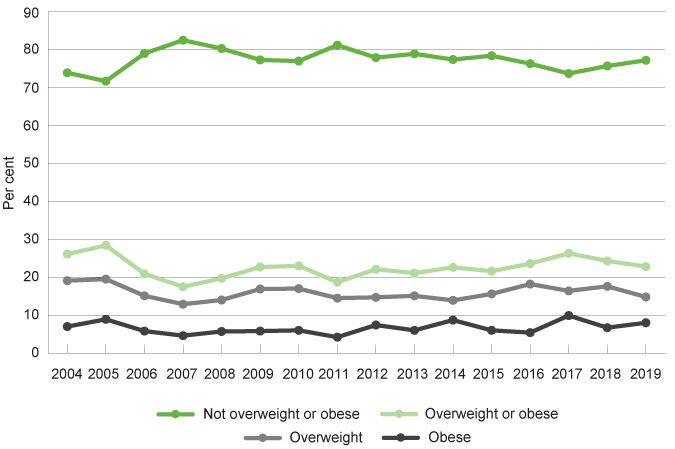

Nearly one-quarter (22.8%) of WA children and young people aged 5 to 15 years were overweight or obese in 2019.

Proportion of children and young people aged 5 to 15 years by BMI categories, per cent, WA, 2004 to 2019

Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends, WA Department of Health (and previous years’ reports)

There is no data publicly available on the physical health of the 1,906 children aged six to 11 years in care in WA. Furthermore, in 2015, only 53.1 per cent of children entering out-of-home care had a medical assessment, as required by Departmental guidelines.

Endnotes

- In this research social exclusion comprised five domains: socioeconomic circumstances, education, connectedness, housing and health service access.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) 2014, Child social exclusion and health outcomes: A study of small areas across Australia, Bulletin 121, June 2014.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) 2008, Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health - Final report of the commission on social determinants of health, WHO.

Last updated August 2021

Being physically healthy is critical for children’s wellbeing as many health conditions in adulthood have their origins in childhood.1 Good health also influences children’s engagement with family, education and friends and supports socio-emotional health.2

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on physical health.3

Almost two-thirds (63.7%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students rated their health as excellent or very good (26.8% excellent and 36.9% very good) while 7.6 per cent said their health was only fair or poor (6.9% fair and 0.7% poor).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Excellent |

28.8 |

25.2 |

26.6 |

29.3 |

22.6 |

26.8 |

|

Very good |

33.4 |

40.1 |

38.8 |

28.9 |

36.3 |

36.9 |

|

Good |

28.7 |

29.0 |

26.8 |

34.1 |

34.7 |

28.7 |

|

Fair |

8.2 |

5.5 |

7.0 |

6.7 |

5.8 |

6.9 |

|

Poor |

0.9 |

N/A |

0.7 |

N/A |

N/A |

0.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences between male and female Year 4 to Year 6 students’ health ratings or between students in regional, remote or metropolitan locations.

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students also reported similar health ratings.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Excellent |

28.5 |

26.7 |

|

Very Good |

27.6 |

37.7 |

|

Good |

35.9 |

28.1 |

|

Fair |

7.1 |

6.9 |

|

Poor |

0.9 |

0.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Having a good nights’ sleep is increasingly being recognised as critical for physical and mental health.4 For physical health, inadequate sleep is associated with a higher risk of children becoming overweight and having poorer overall health.5,6

The recommended hours of sleep is nine to 11 hours for children aged five to 13 years.7

SOS19 asked children what time they usually went to sleep on a school night and what time they usually woke up on a school day. Most students in Years 4 to 6 reported usually going to sleep by 9pm (73.8%) on a school night and waking up by 8am (97.3%) on a school day.8

Around one-third (31.3%) of children in Years 4 to 6 went to sleep before 8pm, and over 90 per cent (91.5%) reported they usually went to sleep before 10pm.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Before 8pm |

31.0 |

31.1 |

28.5 |

38.8 |

43.0 |

31.3 |

|

8pm to 8:59pm |

42.0 |

43.5 |

43.4 |

40.8 |

36.9 |

42.5 |

|

9pm to 9:59pm |

17.1 |

18.2 |

19.2 |

13.6 |

10.7 |

17.7 |

|

10pm to 10:59pm |

5.9 |

5.1 |

6.2 |

2.4 |

6.5 |

5.6 |

|

11pm to 11:59pm |

1.6 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

|

After midnight |

2.4 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

2.6 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A low, but significantly greater proportion of male children than female children went to sleep after midnight (male: 2.4%, female: 1.1%).

There were also differences based on where students lived – with a significantly greater proportion of children in both regional (38.8%) and remote (43.0%) locations going to sleep before 8pm, compared with children in metropolitan areas (28.5%).

Recent research based on the Longitudinal study of Australian Children found that at least 88 per cent of children aged 6 to 11 years met the minimum sleep requirements on a school night.9

This study concluded that children who did not meet the minimum guidelines for sleep were more likely to have poor mental health, be late or absent from school, spend more time on homework and more time on the internet.10

Endnotes

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2011, Young Australians: their health and wellbeing 2011, AIHW, p. 1.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Australia’s Children, AIHW, p. 30.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Evans-Whipp T & Gasser C 2019, Are children and adolescents getting enough sleep? In LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2018, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 29.

- Landhuis CE et al 2008, Childhood sleep time and long-term risk for obesity: A 32-year prospective birth cohort study, Pediatrics, Vol 122, No 5.

- Chaput J et al 2016, Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth, Applied physiology, nutrition and metabolism, Vol 41 (6 Suppl 3).

- Department of Health 2020, Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Young People (5-17 years) – An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep, Australian Government.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 34.

- Ibid, p. 35.

- Ibid, p. 29.

Last updated August 2021

Physical activity makes an important positive contribution to the health and wellbeing of children. Doing regular moderate and/or vigorous physical activity supports the development of healthy bones, muscles, joints and a healthy cardiovascular system. It is also an important element to achieving and maintaining a healthy weight.

Physical activity also enhances cognitive functioning including memory, concentration and the ability to learn.1 Furthermore, it is associated with social and emotional benefits in childhood, including self-regulation and improved self-esteem.2

The current recommendation for physical activity is that children aged five to 12 years should do at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity every day, including at least three days per week where the activities strengthen muscle and bone.3

Data collected on children’s physical activity is often survey-based information, either self-reported daily physical activity or parent-reported daily physical activity. This measure reports data from three key data sources:

- The Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey

- WA Department of Health, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Health Survey

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on physical health.4

In this survey, 66.0 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported they cared very much about staying fit and being physically active, while 23.6 per cent cared some. Just over 10 per cent of students cared a little (7.8%) or not at all (2.6%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Very much |

66.3 |

65.0 |

66.9 |

64.7 |

59.6 |

66.0 |

|

Some |

21.6 |

26.0 |

23.0 |

24.4 |

28.6 |

23.6 |

|

A little |

8.9 |

6.9 |

7.9 |

6.9 |

9.4 |

7.8 |

|

Not at all |

3.2 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

4.0 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Year 4 to 6 students were significantly more likely than high school students to report they cared very much about staying fit and physically active (66.0% compared to 50.8%). For more information refer to the Adequate physical activity measure for the 12 to 17 years age group.

In particular, female students in primary school were significantly more likely than female students in high school to report they cared very much about staying fit and physically active (65.0% compared to 46.1%).

It should be noted that this data is from different cohorts of students in primary school and high school. Younger children may be influenced by more public awareness of the importance of healthy eating through increased public health messaging and advertising (e.g. graphic advertising of the damaging effects of sugary drinks) and a greater focus in schools on healthy eating. Results from future Speaking Out Surveys will show changes over time and determine whether this primary school cohort continue to care more about staying fit and physically active as they move into high school – or if the transition into high school and through adolescence changes students’ views.

There were no significant differences in responses regarding caring about staying fit or physically active between Year 4 to Year 6 students in metropolitan, regional and remote locations.

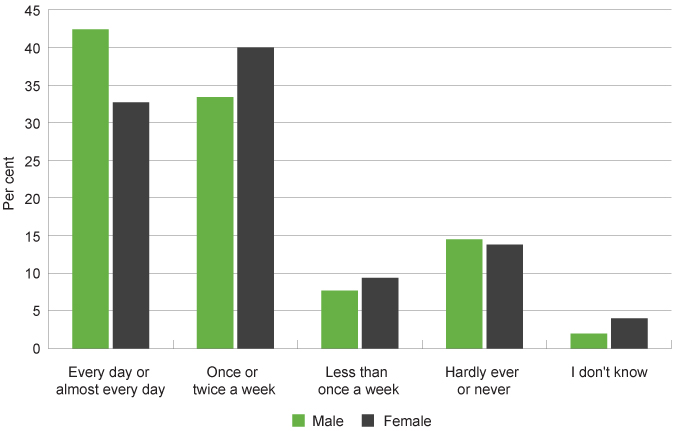

Students in SOS19 were also asked how often they usually spend time practising or playing a sport (like footy training, gymnastics, swimming) outside of school.

Nearly a quarter (22.6%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students said they practise or play a sport outside of school less than once a week or hardly ever or never. Just under thirty-eight per cent said they spend time practising or playing a sport every day or almost every day outside of school, while a similar proportion (36.4%) said they do this once or twice a week.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Every day or almost every day |

42.4 |

32.7 |

38.7 |

34.7 |

37.1 |

37.9 |

|

Once or twice a week |

33.4 |

40.0 |

36.4 |

36.0 |

37.0 |

36.4 |

|

Less than once a week |

7.7 |

9.4 |

7.8 |

10.5 |

10.1 |

8.4 |

|

Hardly ever or never |

14.5 |

13.8 |

14.4 |

15.1 |

10.4 |

14.2 |

|

I don't know |

2.0 |

4.0 |

2.8 |

3.7 |

5.3 |

3.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students reporting how much time they spend practising or playing a sport outside of school by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Female students were significantly less likely than male students to play or practise a sport every day or almost every day outside of school (32.7% compared to 42.4%).

These results are consistent with research reporting that male children and young people are more likely to do more physical activity than female children and young people.5,6

Further analysis of the SOS19 data shows that there is a statistically significant relationship between children in Years 4 to 6 caring a lot about staying fit and being physically active and the time they spend practising or playing a sport outside of school.

There were no significant differences between Year 4 to Year 6 students in metropolitan, regional and remote locations practising or playing sport outside of school.

The WA Department of Health administers the Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System to monitor the health of WA’s general population, which includes interviewing WA parents and carers about the health of their children aged 0 to 15 years.7 In this survey, parents and carers are asked about their children’s activity levels and based on these responses, the Department of Health determine the proportion of WA children meeting the physical activity guidelines.

Research shows that while parent-reported data on physical activity for children under 12 years of age is valid, it has limitations depending on the questions asked (e.g. difficulty estimating unstructured play).8

|

No activity |

1 to 6 sessions |

7 or more sessions |

7 or more sessions |

|

|

2012 |

2.8 |

27.0 |

19.6 |

50.6 |

|

2013 |

5.4* |

28.9 |

21.8 |

43.9 |

|

2014 |

7.5* |

27.6 |

25.1 |

39.8 |

|

2015 |

N/A |

31.0 |

30.3 |

37.6 |

|

2016 |

N/A |

30.4 |

24.7 |

43.2 |

|

2017 |

2.5* |

31.4 |

19.3 |

46.7 |

|

2018 |

8.4* |

23.0 |

22.3 |

46.3 |

|

2019 |

3.6* |

29.3 |

19.1 |

48.0 |

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends. Department of Health, Western Australia (and previous years’ reports) 9

* Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

N/A Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error greater than 50 per cent and is considered too unreliable for general use.

From 2012 to 2015, there was a decline in children aged five to nine years being assessed as meeting the recommended activity level, however from 2016 the proportion of children meeting the recommendation has gradually increased. In 2019, still less than half (48.0%) of WA children aged five to nine years were assessed by their parent/carer as meeting the recommended level of activity.

In 2011–12, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) conducted the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) as part of the Australian Health Survey.10 In this survey, parents were asked about their child’s previous week’s physical activity and data was collected by jurisdiction.11 Results showed that the proportion of WA children and young people aged two to 17 years meeting the physical activity recommendations in 2011–12 was very low (32.5%), although this was in line with other states and territories in Australia.

In 2017–18, the Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted the National Health Survey, in this survey they reported on the physical activity of young people and adults aged 15 years and over. This survey did not consider children under 15 years of age.

Data and research has consistently found that male children are more likely to do more physical activity than female children.12,13

Consistent with the SOS19 data, the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports that a higher proportion of male children and young people than female children and young people generally meet the recommended activity level.14

|

Male |

Female |

|

|

2012 |

55.0 |

42.7 |

|

2013 |

49.1 |

33.6 |

|

2014 |

39.8 |

40.3 |

|

2015 |

48.5 |

28.0 |

|

2016 |

39.9 |

39.5 |

|

2017 |

46.2 |

32.5 |

|

2018 |

45.4 |

34.5 |

|

2019 |

45.2 |

32.3 |

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends, WA Department of Health (and previous years’ reports) 15

In 2008, researchers from Edith Cowan University and the University of WA conducted the Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS) in WA.16 In this study participants wore pedometers and completed exercise diaries. The researchers found significant differences between male and female respondents. While only 41.2 per cent of male primary school students reported activity that met the recommended guidelines, even fewer female primary school students (27.4%) reported activity that met the recommended guidelines.17 This survey has not been repeated.

Aboriginal children

There is limited regularly reported data on the physical activity of WA Aboriginal children or children in metropolitan, regional and remote locations. The WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System does not provide disaggregated information on physical activity for Aboriginal children or by geographic location.

In SOS19, a marginally lower proportion of Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students than non-Aboriginal students reported they cared very much about staying fit or physically active (Aboriginal: 62.7%, non-Aboriginal 66.3%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Very much |

62.7 |

66.3 |

|

Some |

22.8 |

23.7 |

|

A little |

9.9 |

7.6 |

|

Not at all |

4.6 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

However, Aboriginal students were more likely to practise or play a sport every day (44.4% compared to 37.4%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Every day or almost every day |

44.4 |

37.4 |

|

Once or twice a week |

29.7 |

36.9 |

|

Less than once a week |

8.1 |

8.5 |

|

Hardly ever or never |

9.2 |

14.6 |

|

I don't know |

8.6 |

2.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

This is consistent with other data that suggests WA Aboriginal children and young people are generally more physically active than non-Aboriginal children and young people in WA.

In 2012–13, the ABS conducted the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity. They reported that a higher proportion of WA Aboriginal children and young people (45.6%) aged five to 17 years in non-remote areas met the physical activity recommendation compared with non-Aboriginal children and young people (40.5%).18

In remote areas across Australia,19 over four in five (86%) Aboriginal children aged five to eight years and an equivalent proportion of nine to 11 year olds (87%) did more than 60 minutes of physical activity on the day prior to the interview. 20

There is no information available on the physical activity of WA Aboriginal children in remote areas.

A 2018 report (based on the AusPlay survey data from that year) found that Australian children are less likely to participate in organised physical activity outside school hours if:

- they come from a low-income family

- they live in a remote or regional area

- a parent speaks a Language Other Than English (LOTE) at home

- they have three or more siblings.21

The survey also found that only 58 per cent of Australian children and young people from low-income families participate in organised physical activity outside of school compared to 73 per cent of children and young people from middle income families and 84 per cent of children and young people from high income families.22

The WA Government provides financial assistance to encourage WA children and young people to engage in sporting activities through the KidSport program. The program provides up to $150 per year towards fees for approved sporting clubs for children and young people aged five to 18 years from low income families.

The 2019–20 Annual Report of the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries stated that the KidSport program provided 18,596 vouchers (approx. $2.5m worth) throughout the year, including 2,300 Aboriginal applicants, 1,000 from the CALD community and 1,200 children with a disability.23

The report noted that restrictions on community sport between March and June 2020 due to COVID-19 had impacted the number of vouchers issued, but that they were experiencing a significant increase in the number of applications with the resumption of community sport in early 2020–21.24

No data has been publicly reported on whether eligible children and young people have increased their physical activity as a result of the program.

Endnotes

- WA Department of Sport and Recreation 2015, Brain Boost: how sport and physical activity enhance children’s learning, Centre for Sport and Recreation Research, Curtin University.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Physical activity across the life stages, Cat No PHE 225, AIHW.

- Department of Health, Guidelines for healthy growth & development for children & young people (5 to 17 years), Australian Government [website].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Martin K et al 2008, Move and Munch Final Report: Trends in physical activity, nutrition and body size in Western Australian children and adolescents: the Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS), Department of Sports and Recreation, WA Government.

- Telford RM et al 2016, Why Are Girls Less Physically Active than Boys? Findings from the LOOK Longitudinal Study, PloS one, Vol 11 No 3.

- The WA Department of Health’s, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System is a continuous data collection which was initiated in 2002 to monitor the health status of the general population. In 2019, 546 parents/carers of children aged 0 to 15 years were randomly sampled and completed a computer assisted telephone interview between January and December, reflecting an average participation rate of just over 90 per cent. The sample was then weighted to reflect the WA child population.

- Bauman A et al 2019, Physical activity measures for children and adolescents - recommendations on population surveillance: an evidence check rapid review, Sax Institute, p. 14.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- To assess against the physical guideline recommendations and relating factors, the survey considered: number of days the child did physical activity for at least 60 minutes in the week prior to interview; the type and duration of physical activity undertaken for transport to or from school/place of study and other places on each of the seven days prior to interview; the type and duration of organised and non-organised moderate to vigorous physical activities undertaken on each of the seven days prior to interview. This was determined through a discussion with a parent/carer with child involvement where possible. Source: 4363.0.55.001 - Australian Health Survey: Users' Guide, 2011-13 - Child Physical Activity (5 to 17 years).

- In subsequent Australian Health Surveys (and National Health Surveys) the physical activity data has not been collected by this age group and jurisdiction.

- Martin K et al 2008, Move and Munch Final Report: Trends in physical activity, nutrition and body size in Western Australian children and adolescents: the Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS), Department of Sports and Recreation, WA Government.

- Telford RM et al 2016, Why Are Girls Less Physically Active than Boys? Findings from the LOOK Longitudinal Study, PloS one, Vol 11 No 3.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- This study used a mixed methods approach of pedometers and questionnaires to collect data on physical activity.

- Martin K et al 2008, Move and Munch Final Report: Trends in physical activity, nutrition and body size in Western Australian children and adolescents: the Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS), Department of Sports and Recreation, WA Government, p. vi.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4727.0.55.004 - Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Table 9.3 Whether met physical and screen-based activity recommendations by Indigenous status by selected characteristics, Children aged 5–17 years in non-remote areas (proportion).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics note that testing indicated that the way the guidelines had been developed into a survey instrument for use in non-remote areas did not work well in more remote areas of Australia. As a result, in remote areas, minimal data was collected only for the day prior to the interview for a range of physical activities, with no measurement of the intensity of these activities.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4727.0.55.004 - Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Remote areas (5 years and over), Table 18.3 Physical activity and sedentary behaviour by age then sex, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 5-17 years in remote areas (proportion).

- Australian Sports Commission 2018, AusPlay Focus: Children’s Participation in Organised Physical Activity Outside of School Hours, Australian Government, p. 12.

- Australian Sports Commission 2018, AusPlay Focus: Children’s Participation in Organised Physical Activity Outside of School Hours, Australian Government. In this report, low income families were defined as those with gross (before tax) household income of less than $55,000 per annum; middle income families were defined as those with gross (before tax) household income between $55,000 and $174,999 per annum; and high income families are those with gross (before tax) household income of $175,000 or more per annum.

- Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries 2020, Annual Report: 2019-20, WA Government, p. 95

- Ibid.

Last updated August 2021

Over the past decade, it has been increasingly recognised that while media devices provide significant opportunities for learning and development, high levels of screen-based activities can be detrimental to children’s health and wellbeing.1 A high level of screen time is associated with sedentary behaviour, low quality sleep, obesity and for some eye health issues.2,3,4 Although, evidence is mixed, screen time is also increasingly being linked to mental health issues for young people, including anxiety and depression.5,6

Screen time is therefore important for children’s wellbeing from two perspectives; as a measure of how much time is spent in sedentary activities (not being active) and how much time is spent on interacting and managing social media (if used), which may impact their mental health and self-esteem and disrupt healthy sleep patterns.

The Australian Physical activity and exercise guidelines for children and young people (5 to 17 years) recommend that the use of electronic media for entertainment be limited to a maximum of two hours per day and long periods of sitting should be broken up as often as possible.

The guidelines are principally focused on reducing sedentary behaviour – based on the theory that more hours spent viewing a screen means less physical exercise. Although it should be noted that screen time does not report on overall levels of sedentary behaviour, which can include other activities such as reading, sitting or lying down.7

Children now grow up with screens as an integral part of their education and social development, and as more children have access to mobile devices it is increasingly difficult to measure daily screen time.

Due to this shift, it is more critical to focus on the quality of the content being consumed rather than a simple focus on the number of hours of screen time. It is also essential to ensure children do enough physical activity and get high quality sleep.

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on access and use of technology.8

While the survey did not ask about the number of hours of daily usage, it is evident from the data that many children use screens on a daily basis for a range of activities and it is likely many do not meet the guidelines given they use screens for entertainment, socialising, communicating, gaming and for educational purposes.

Overall, 43.0 per cent of students in Year 4 to Year 6 reported they spend time using the internet on a smartphone or computer every day or almost every day when they are not at school. This proportion was significantly lower than the proportion for Year 7 to Year 12 students (86.8%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Every day or almost every day |

45.7 |

40.4 |

44.6 |

39.4 |

34.4 |

43.0 |

|

Once or twice a week |

29.4 |

30.0 |

30.3 |

25.8 |

32.7 |

29.7 |

|

Less than once a week |

10.2 |

12.2 |

10.7 |

12.9 |

13.0 |

11.3 |

|

Hardly ever or never |

13.2 |

14.7 |

12.7 |

19.2 |

15.1 |

14.0 |

|

I don't know |

1.5 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

2.7 |

4.8 |

2.0 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A lower proportion of children in remote locations than metropolitan locations spent time every day or almost every day using the internet (34.4% compared to 44.6%).

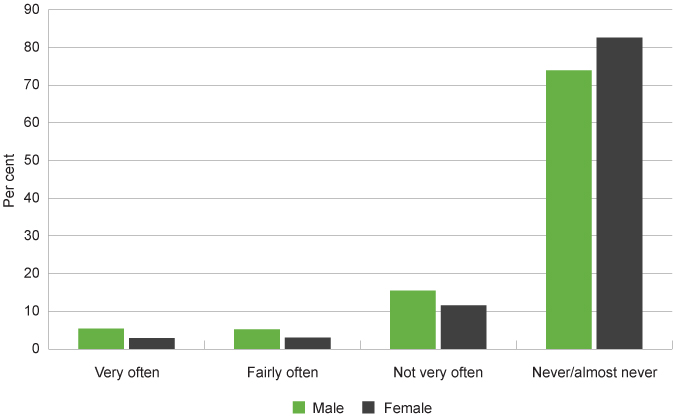

Students in Year 4 to Year 6 were asked how often they go without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games. Most students (78.0%) reported that they never or almost never go without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games. However, a small, but significant minority of students in Year 4 to Year 6 reported that they go without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games very often (4.3%) or fairly often (4.2%).

Students in regional areas were more likely than those in metropolitan and remote areas to report they never or almost never go without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games (84.5% compared to 77.2% and 71.0%, respectively).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Very often |

5.4 |

2.9 |

4.6 |

2.4 |

6.3 |

4.3 |

|

Fairly often |

5.2 |

3.0 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

8.9 |

4.2 |

|

Not very often |

15.5 |

11.6 |

14.3 |

9.3 |

13.8 |

13.5 |

|

Never/almost never |

73.9 |

82.6 |

77.2 |

84.5 |

71.0 |

78.0 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Female children were significantly more likely than male children to report never or almost never going without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games (female: 82.6%; male: 73.9%).

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students reporting how often they go without eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

In contrast, female students in high school were significantly less likely than male high school students to never or almost never go without eating or sleeping because of their mobile phones (female: 60.9%; male: 70.6%). For more information, refer to the Screen time measure in the Physical health indicator for the 12 to 17 years age group.

Further analysis of the SOS19 data shows that there is a significant association between children not eating or sleeping because of the internet or electronic games and having low self-esteem (not feeling happy with themselves).9

The WA Department of Health administers the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System to monitor the health of WA’s general population, interviewing WA parents and carers about the health of their children aged 0 to 15 years.10 In this survey they ask parents and carers about their children’s screen-based activities and based on these responses reported that the majority (78.6%) of WA children and young people aged five to 15 years met the guidelines in 2019. The data is not disaggregated further by age and therefore we have not reproduced it here.

The last Australian Bureau of Statistics survey with data on children’s screen time was the Australian Health Survey: Physical Activity: 2011–2012. In this survey the average time Australian five to eight year-old children spent on sedentary screen-based activities per day was 98 minutes, while nine to 11 year-old Australian children spent 119 minutes per day.11 These average times are just below the recommended maximum of two hours (120 minutes) per day. These times are likely to have increased significantly over the past 10 years due to the substantial increase in availability and popularity of mobile devices and related applications.

Data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children similarly found that children aged six to seven years spent 94 minutes per day on screen-based activities on average. Television was the main medium for screen-based activities for all age groups, with children aged six to seven years watching an average of 80 minutes of television per weekday.12

In this research, the proportion of children who met the screen-based activity guidelines was similar among male and female children. However, there were gender differences in the types of activities. Male children were significantly more likely than female children to spend at least an hour per day on electronic games.13

The findings from this research also suggest that children and young people who enjoy doing physical activities spend less time in front of screens.14 This highlights the importance of engaging children and young people in fun physical activities to provide the foundation for an active life.

In 2020, the Australian Communications and Media Authority published the Kids and mobiles – How Australian children are using mobile phones report which looked at mobile phone ownership and usage amongst Australian children and young people.15 This survey is conducted annually by Roy Morgan and involves interviewing approximately 2,500 children and young people.16

In 2020, the survey found that almost half (46.3%) of children aged six to 13 years used a mobile phone (increased from 41.0% in 2015), with around a third (33%) owning their own mobile phone.17

Mobile phone usage increases as children age with one-quarter (25.0%) of children aged six to seven years having access to a mobile phone and over 80 per cent (81.6%) of 12 to 13 year-olds using a mobile phone. Since 2015, mobile phone usage amongst children has markedly increased across all age groups, except children aged 10 to 11 years.

|

6 to 7 years |

8 to 9 years |

10 to 11 years |

12 to 13 years |

All |

|

|

2015 |

20.2 |

25.2 |

45.6 |

71.6 |

41.0 |

|

2016 |

19.8 |

27.6 |

40.6 |

73.6 |

40.8 |

|

2017 |

23.3 |

30.3 |

44.9 |

79.2 |

44.8 |

|

2018 |

22.4 |

34.9 |

49.2 |

79.4 |

46.9 |

|

2019 |

21.1 |

32.0 |

51.0 |

80.7 |

46.6 |

|

2020 |

25.0 |

30.7 |

46.5 |

81.6 |

46.3 |

Source: Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones – accessibility data file

This survey also asked children about whether they owned the mobile phone they used. In 2020, one-third (32.6%) of children aged six to 13 years owned their own mobile phone. This includes three-quarters (75.6%) of 12 to 13 year-olds and one-third (32.6%) of 10 to 11 year-olds and 15 per cent of eight to nine year-olds.

|

6 to 7 years |

8 to 9 years |

10 to 11 years |

12 to 13 years |

All |

|

|

2015 |

3.0 |

7.7 |

28.4 |

65.1 |

26.5 |

|

2016 |

2.3 |

10.7 |

26.6 |

66.3 |

27.0 |

|

2017 |

5.0 |

11.5 |

31.5 |

73.0 |

30.8 |

|

2018 |

3.9 |

12.8 |

31.9 |

72.0 |

30.7 |

|

2019 |

5.1 |

14.2 |

35.6 |

73.9 |

32.7 |

|

2020 |

4.8 |

15.3 |

32.6 |

75.6 |

32.6 |

Source: Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones – accessibility data file

This data shows that the proportion of eight to nine year-olds owning their own mobile phone has doubled from 7.7 per cent in 2015 to 15.3 per cent in 2020.

Children aged six to 11 years most commonly used a mobile phone for playing games, whereas for 12 to 13 year-olds the most common activity was to send or receive texts.

|

6 to 9 years |

10 to 11 years |

12 to 13 years |

|

|

Play games |

67.6 |

70.5 |

74.5 |

|

Take photos/videos |

56.8 |

66.9 |

80.0 |

|

Use apps |

54.0 |

66.8 |

77.5 |

|

Send or receive texts |

26.2 |

63.8 |

84.8 |

|

Call parents/family |

42.2 |

54.6 |

77.3 |

|

Listen to music |

39.2 |

55.2 |

72.5 |

|

Receive calls from parents/family |

34.6 |

52.2 |

76.7 |

|

Send or receive picture messages |

20.2 |

46.4 |

65.3 |

|

Access the internet |

24.8 |

45.8 |

61.0 |

|

Call my friends |

12.7 |

42.5 |

68.6 |

Source: Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones – accessibility data file

Aboriginal children

Research suggests that Aboriginal families are generally less likely than non-Aboriginal families to have access to the internet at home.18

The ABS conducted the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity in 2012–13 and found that 46.5 per cent of WA Aboriginal children and young people aged five to 17 years in non-remote areas met the screen-based activity recommendation on all three days prior to the survey, compared with only 36.4 per cent of WA non-Aboriginal children and young people.19

There is no information available on the proportion of WA Aboriginal children in remote areas meeting the screen-based activity (sedentary behaviour) recommendations.

In SOS19, similar proportions of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 6 students report using the internet on a smartphone or computer when they are not at school every day (42.9% compared to 43.0%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Every day or almost every day |

42.9 |

43.0 |

|

Once or twice a week |

23.8 |

30.1 |

|

Less than once a week |

9.9 |

11.4 |

|

Hardly ever or never |

17.1 |

13.8 |

|

I don't know |

6.3 |

1.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Due to the increasing accessibility and popularity of mobiles devices and screen-based activities, the impact of increased use on children’s physical and emotional wellbeing is critical to monitor now and into the future.

Endnotes

- Yu M and Baxter J 2016, Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Laurson KR et al 2014, Concurrent associations between physical activity, screen time, and sleep duration with childhood obesity, International Scholarly Research Notices: Obesity, Vol 2014.

- Fuller C et al 2017, Bedtime Use of Technology and Associated Sleep Problems in Children, Global Pediatric Health, Vol 4.

- Stiglic N and Viner RM 2019, Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews, BMJ Open, Vol 9.

- Khouja J et al 2020, Is screen time associated with anxiety or depression in young people? Results from a UK birth cohort, BMC Public Health, Vol 19, No 82.

- Barthorpe A et al 2020, Is social media screen time really associated with poor adolescent mental health? A time use diary study, Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol 274.

- WA Department of Health 2019, Sedentary behaviour, WA Government, [website].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- The WA Department of Health’s, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System is a continuous data collection which was initiated in 2002 to monitor the health status of the general population. In 2017, 780 parents/carers of children aged 0 to 15 years were randomly sampled and completed a computer assisted telephone interview between January and December, reflecting an average participation rate of just over 90 per cent. The sample was then weighted to reflect the WA child population.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 43640 Australian Health Survey - National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–12 – Table 20.1 Average time spent on sedentary screen-based activity, children aged 5–17 years (minutes), ABS.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2016, Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies, pp. 102, 106.

- Yu M and Baxter J 2016, Australian children’s screen time and participation in extracurricular activities, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 114.

- Ibid, p. 119-120.

- Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones, Australian Government [online].

- Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones - Methodology, Australian Government.

- Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) 2020, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones – accessibility data file, Australian Government.

- Radoll P & Hunter B 2017, Dynamics of the digital divide: Working Paper No. 120/2017, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, p. 10.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 4727.0.55.004 - Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Table 9.3 Whether met physical and screen-based activity recommendations by Indigenous status by selected characteristics, children aged 5–17 years in non-remote areas (proportion), ABS.

Last updated August 2021

Diet has a strong influence on wellbeing from birth. Children need to have a nutritious and balanced diet to grow and develop in a healthy way, and to reduce the risk of developing chronic diseases later in life. Research has shown that eating a wide variety of nutritious foods and limiting consumption of fatty and sugary foods is critical to healthy development and growth.1

Eating regular meals is important because eating irregularly can increase the risk of developing an eating disorder2 and has been linked with a higher risk of diseases such as high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes and obesity.3

The Australian Government publishes the Australian Dietary Guidelines to provide guidance on foods, food groups and dietary patterns that protect against chronic disease and provide the nutrients required for optimal health and wellbeing. The guidelines are:

- To achieve and maintain a healthy weight, be physically active and choose amounts of nutritious food and drinks to meet your daily energy needs.

- Enjoy a wide variety of nutritious foods from the five food groups every day.

- Limit intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars and alcohol.

- Encourage, support and promote breastfeeding.

- Care for your food; prepare and store it safely.

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on physical health.4

Overall, one-half (50.1%) of Year 4 to Year 6 students reported caring very much about eating healthy food, 38.3 per cent of students reported only caring some, 8.9 per cent caring a little and 2.8 per cent not caring at all.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Very much |

47.7 |

51.6 |

48.9 |

53.4 |

54.4 |

50.1 |

|

Some |

40.9 |

36.1 |

39.8 |

35.0 |

30.1 |

38.3 |

|

A little |

7.8 |

10.1 |

8.8 |

7.3 |

12.9 |

8.9 |

|

Not at all |

3.5 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

4.2 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences in responses between male and female students or students in different geographical regions. There were also no significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.5

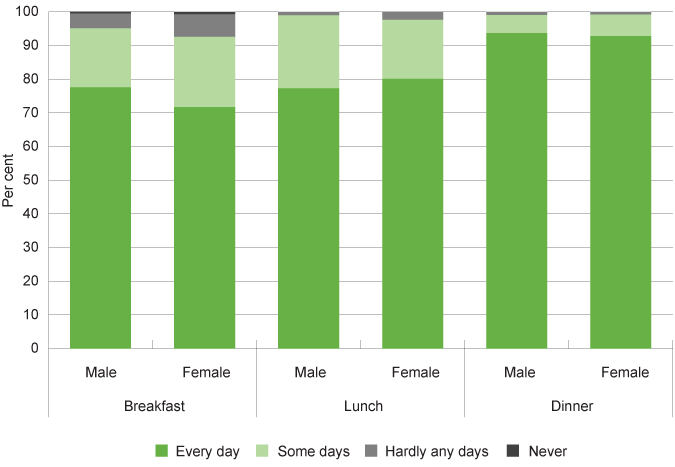

Students in SOS19 were asked how often they usually ate breakfast, lunch and dinner. Across all students in Years 4 to 6, 74.8 per cent reported eating breakfast, 78.4 per cent reported eating lunch and 93.1 per cent reported eating dinner every day.6

Female students in Years 4 to 6 were much less likely than male students to say that they ate breakfast every day (71.7% compared to 77.6% for males). There were no substantial gender differences regarding eating lunch or dinner.

|

Breakfast |

Lunch |

Dinner |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

Every day |

77.6 |

71.7 |

77.3 |

80.1 |

93.7 |

92.8 |

|

Some days |

17.5 |

20.9 |

21.4 |

17.4 |

5.2 |

6.1 |

|

Hardly any days |

4.4 |

6.7 |

1.1 |

2.4 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

|

Never |

0.6 |

0.7 |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students saying they eat breakfast, lunch or dinner every day, some days, hardly any days or never by meal and gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Notably, across all three regular meal categories, female high school students were less likely than male students to say that they usually ate these meals every day. In particular, female students were significantly less likely than male students to say that they ate breakfast every day, with a majority (61.9%) of female students not eating breakfast every day compared to 41.5 per cent of male students.7 For more information refer to the Healthy diet measure in the age group 12 to 17 years.

Research suggests that adolescents, particularly young females, often worry about their weight and can idealise ultra-thin bodies. This can lead to attempts to control their weight through unhealthy eating behaviours including meal skipping and using extreme diets.8,9 Thus, the proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 female students not eating breakfast every day (29.3%) may be related to these students starting to restrict their eating due to concerns about their weight and body image.

A key component of the guidelines are the recommended daily serves of fruit and vegetables.

|

4 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

|

|

Minimum recommended number of serves of vegetables per day |

||

|

Boys |

4½ |

5 |

|

Girls |

4½ |

5 |

|

Minimum recommended number of serves of fruit per day |

||

|

Boys |

1½ |

2 |

|

Girls |

1½ |

2 |

Source: National Health and Medical Research Council 2013, Australian Dietary Guidelines

The guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumption were revised by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in 2013. This had the effect of increasing the recommended serves of vegetables and reducing the recommended amount of fruit for some age groups.10

The WA Department of Health administers the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System to monitor the health of WA’s general population, which includes interviewing WA parents and carers about the health of their children aged 0 to 15 years.11 In this survey they ask parents and carers about their children’s eating behaviours and based on these responses determine the proportion of WA children and young people meeting the fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines.

This survey reports little change in children’s fruit and vegetable consumption since 2014.

A very high proportion (96.0%) of children aged four to eight years of age are meeting the guidelines for fruit consumption. A smaller, but still substantial proportion (61.3%) of children in the older age groups are meeting the requirements for fruit consumption.

|

Consuming recommended serves of fruit |

Consuming recommended serves of vegetables |

|||

|

4 to 8 years |

9 to 15 years |

4 to 8 years |

9 to 15 years |

|

|

2014 |

97.3 |

64.0 |

11.7 |

8.8 |

|

2015 |

99.2 |

62.7 |

24.5 |

6.5 |

|

2016 |

97.8 |

59.6 |

12.4 |

8.3 |

|

2017 |

98.5 |

61.7 |

7.4* |

4.1 |

|

2018 |

96.3 |

65.4 |

17.1 |

6.2* |

|

2019 |

96.0 |

61.3 |

7.8 |

7.6* |

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends. Department of Health, Western Australia (and previous years’ reports) 12

*Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

Note: As the consumption of half serves is not captured in the questions currently asked in the WA Health survey, for the purposes of reporting, the recommended number of serves is rounded down to the nearest whole number.

Only a very small proportion of WA children and young people are meeting the recommended guidelines for vegetable consumption. In both age groups the proportion of children and young people eating sufficient vegetables is very low at less than eight per cent in each case.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted the National Health Survey in 2014–15 and 2017–18 which reported on daily intake of fruit and vegetables for children. This data is relatively consistent with the results of the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, although the proportion of children meeting the recommended guidelines for fruit consumption are lower.

|

2014-15 |

2017-18 |

||||

|

4 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

4 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

||

|

Fruit |

WA |

71.9 |

61.1* |

85.1 |

80.2* |

|

Australia |

73.1 |

69.9 |

77.8 |

74.2 |

|

|

Vegetables |

WA |

5.0 |

2.6 |

6.8 |

0.0** |

|

Australia |

3.3 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

5.9 |

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics: National Health Survey: Updated Results, 2014–15 — Australia, Table 17.3 Children's daily intake of fruit and vegetables and main type of milk consumed, Proportion of persons, WA and Australia and National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18 — Australia, Table 17.3 Children's consumption of fruit, vegetables, selected sugar sweetened and diet drinks, Proportion of persons, WA and Australia

* Proportion has a margin of error >10 percentage points which should be considered when using this information.

** The zero result means there was no data collected for this category in the sample. It does not represent a population estimate.

The ABS also conducted the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey in 2018–19.

|

4 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

|

|

Adequate daily fruit intake |

69.6 |

61.7 |

|

Adequate daily vegetable intake |

2.4 |

3.9 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018–19, Table 17.3 Selected dietary indicators, by age, sex and remoteness, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 2–17 years, 2018–19, Proportion of persons

Consistent with the results for all WA children, the majority of Aboriginal children in Australia were not consuming sufficient vegetables in 2018–19.

Fresh fruit and vegetables have less availability and affordability in remote and regional locations, where a large proportion of Aboriginal children and young people live.13 The 2013 WA Food Access and Cost Survey found that food costs increased significantly with distance from Perth, and cost substantially more in very remote areas. At the same time, fruit and vegetable quality was generally lower in remote communities.14

Research also suggests that people living in poverty or with low incomes are more likely to eat calorie rich (high fat, high sugar) foods. The poverty rate for Aboriginal Australians is significantly higher than for non-Aboriginal Australians.15

Refer to the following resource for a more detailed discussion on nutrition among Aboriginal communities:

Lee A and Ride K 2018, Review of nutrition among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

The low level of vegetable consumption for all WA children is of significant concern.

Guideline three of the Australian Dietary Guidelines also recommends that individuals should limit intake of foods and drinks containing saturated fats and added sugars such as biscuits, cakes, confectionary, sugar-sweetened soft drinks and cordials, fruit drinks and sports drinks.16

Reducing children’s sugar consumption has been highlighted as particularly critical. Sugar consumption in childhood is directly linked to being overweight or obese, and having dental health conditions, both of which impact lifelong health.17 There is also strong evidence to suggest that foods and drinks consumed by children early in life establish their preferences for tastes (e.g. sweetness) later in life.18

Unlike serves of fruit and vegetables, the consumption of sugar is more complex to measure as sugar occurs naturally in many foods. The World Health Organisation recommends reducing the intake of free sugars – which include sugars added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer plus those naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices – to less than 10 per cent of total energy intake in both adults and children.19

There is limited data on WA children’s consumption of sugar.

The ABS National Health Survey collects data on children’s consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks based on parent reports.

|

4 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

|

|

WA |

67.6 |

64.6* |

|

Australia |

69.4 |

56.3 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Health Survey, First Results 2017–18 – Australia and Western Australia, Table 17.3 Children's consumption of fruit, vegetables, and selected sugar sweetened and diet drinks

* Proportion has a high margin of error and should be used with caution.

Note: Sugar-sweetened drinks includes soft drink, cordials, sports drinks or caffeinated energy drinks. May include soft drinks in ready to drink alcoholic beverages. Excludes fruit juice, flavoured milk, 'sugar free' drinks, or coffee / hot tea.

In the 2017–18 survey they report that 67.6 per cent of WA children aged four to eight years and 64.6 per cent of children aged nine to 11 years were reported by their parents as not usually consuming sugar-sweetened drinks. This was similar to the results for Australia for the 4 to 8 years age group, while, subject to the high margin of error, a higher proportion of WA children aged 9 to 11 than Australian children the same age do not consume sugar-sweetened drinks.

Endnotes

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2013, Australian Dietary Guidelines: Providing the scientific evidence for healthier Australian diets, Canberra, National Health and Medical Research Council.

- O’Connor M et al 2017, Eating problems in mid-adolescence, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, pp. 113-124.

- Pot G et al 2016, Meal irregularity and cardiometabolic consequences: Results from observational and intervention studies, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, Vol 75 No 4.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- O’Connor M et al 2017, Eating problems in mid-adolescence, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2017, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 117.

- Aparicio-Martinez P et al 2019, Social Media, Thin-Ideal, Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating Attitudes: An Exploratory Analysis, International Journals of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol 16.

- Prior to 2013, children aged four to 11 years of age were recommended to eat at least one serve of fruit each day, while 12 to 18 year olds were recommended to eat three serves. While children aged four to seven years of age were recommended to eat at least two serves of vegetables each day, eight to 11 year olds eat at least three serves a day and 12 to 15 year olds eat at least four serves a day. NHMRC, Australian dietary guidelines for children and adolescence 2003 (since rescinded).

- The WA Department of Health’s, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System is a continuous data collection which was initiated in 2002 to monitor the health status of the general population. In 2017, 780 parents/carers of children aged 0 to 15 years were randomly sampled and completed a computer assisted telephone interview between January and December, reflecting an average participation rate of just over 90 per cent. The sample was then weighted to reflect the WA child population.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2015, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2014 Report, 2.19 Dietary behaviours, Australian Government.

- Pollard CM et al 2015, Food Access and Cost Survey 2013 Report, WA Department of Health.

- Davidson P et al 2018, Poverty in Australia, 2018, Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS), UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership Report No 2, ACOSS, p. 65.

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2013, Australian Dietary Guidelines: Providing the scientific evidence for healthier Australian diets, National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Diep H et al 2017, Factors influencing early feeding of foods and drinks containing free sugars—a birth cohort study, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol 14 No 10.

- Ibid.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) 2015, Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children, WHO.

Last updated August 2021

Being overweight or obese in childhood increases the likelihood of poor physical health in both the short and long term. Being obese increases a child’s risk of a range of conditions such as asthma, Type 2 diabetes1 and cardiovascular conditions.2 In recent years more children are being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, when it was previously considered a disease of adulthood.3

Children who are overweight or obese are more likely to be overweight or obese in adulthood.4 Overweight or obese children who continue to be overweight or obese in adulthood face a higher risk of developing coronary heart disease, diabetes, certain cancers, gall bladder disease, osteoarthritis and endocrine disorders.5

Obesity in children is also associated with a number of psychosocial problems, including social isolation, discrimination and low self-esteem.6

While obesity is often the focus of research and data, some children and young people are underweight which can be related to body image issues and eating disorders.

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on physical health.7

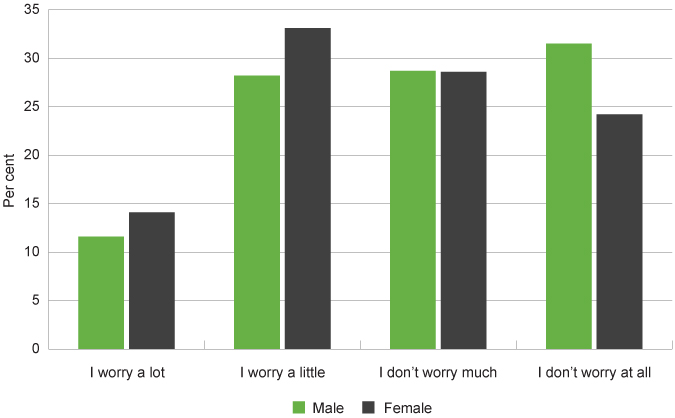

The proportion of male Year 4 to Year 6 students who do not worry at all about their weight at all is significantly higher than that of female students (31.5% compared to 24.2%).

This difference increases as students move through school with the proportion of female students in Years 7 to 12 reporting not worrying at all about their weight falling to 11.7 per cent, while the proportion for male high school students remains relatively unchanged (31.6%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

I worry a lot |

11.6 |

14.1 |

13.1 |

11.9 |

13.9 |

13.0 |

|

I worry a little |

28.2 |

33.1 |

31.1 |

29.3 |

30.7 |

30.8 |

|

I don't worry much |

28.7 |

28.6 |

29.2 |

26.4 |

23.8 |

28.3 |

|

I don't worry at all |

31.5 |

24.2 |

26.6 |

32.5 |

31.6 |

28.0 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students reporting they worry a lot, a little, don’t worry much or don’t worry at all about their weight by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences in worrying about weight between geographical regions.

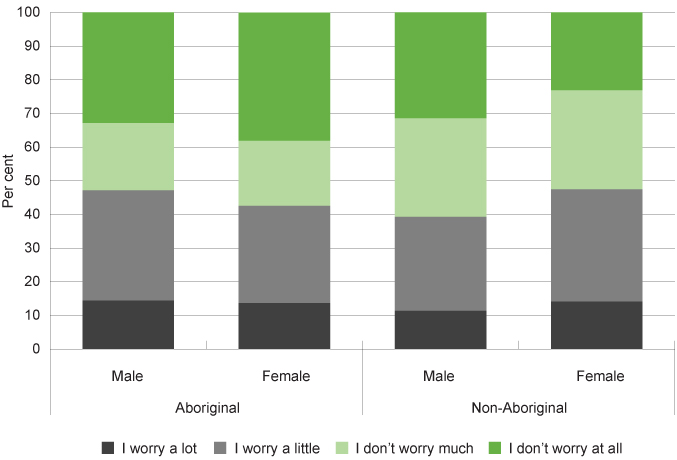

Aboriginal students were more likely than non-Aboriginal students to not worry at all about their weight (35.2% compared to 27.4%). In particular, female Aboriginal students were much more likely than female non-Aboriginal students to not worry about their weight at all (38.2% compared to 23.0%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|||||

|

Male |

Female |

All |

Male |

Female |

All |

|

|

I worry a lot |

14.4 |

13.7 |

14.0 |

11.4 |

14.1 |

12.9 |

|

I worry a little |

32.8 |

28.9 |

31.2 |

27.9 |

33.4 |

30.8 |

|

I don't worry much |

20.0 |

19.3 |

19.4 |

29.3 |

29.4 |

29.0 |

|

I don't worry at all |

32.9 |

38.2 |

35.3 |

31.5 |

23.0 |

27.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 students reporting they worry a lot, a little, don’t worry much or don’t worry at all about their weight by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

The WA Department of Health administers the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System to monitor the health of WA’s general population, interviewing WA parents and carers about the health of their children aged 0 to 15 years.8 In this survey parents and carers of children aged five to 15 years are asked to provide their child’s height without shoes and weight without clothes or shoes. A Body Mass Index (BMI) is derived from these figures by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared. BMI scores take into account the age and sex of the young person.9

The use of BMI to measure healthy weight is contested, particularly as it does not distinguish between fat and muscle or the location of the fat.10 BMI is not a diagnostic tool. If a child or young person has a high BMI for their age and sex, they should be referred to a health professional for further assessment considering physical activity and diet, and using other measures such as skin fold thickness or dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA).11,12,13 BMI is however considered an appropriate tool for population level measurement and trend analysis.14

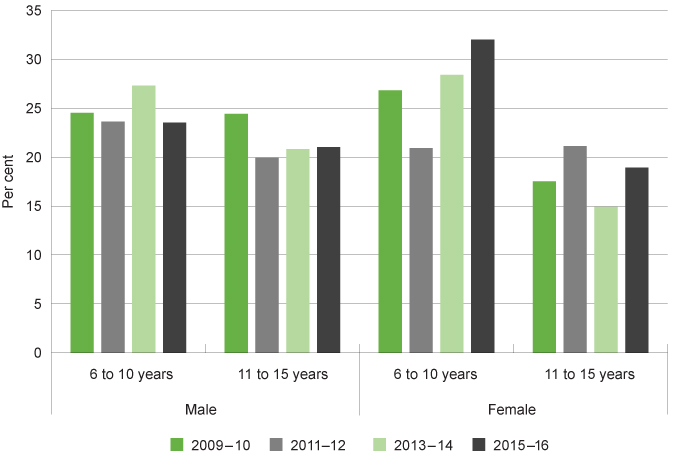

In 2019, just under one-quarter (22.8%) of WA children and young people aged five to 15 years were categorised as overweight or obese. This proportion has been relatively stable over time, however the past two years have seen successive decreases.

|

Not overweight |

Overweight |

Overweight |

Obese |

|

|

2004 |

73.9 |

26.1 |

19.1 |

7.0* |

|

2005 |

71.7 |

28.4 |

19.5 |

8.9 |

|

2006 |

79.0 |

20.9 |

15.1 |

5.8 |

|

2007 |

82.5 |

17.5 |

12.9 |

4.6* |

|

2008 |

80.3 |

19.7 |

14.0 |

5.7 |

|

2009 |

77.3 |

22.7 |

16.9 |

5.8 |

|

2010 |

77.0 |

23.0 |

17.0 |

6.0 |

|

2011 |

81.2 |

18.7 |

14.5 |

4.2* |

|

2012 |

77.9 |

22.1 |

14.7 |

7.4 |

|

2013 |

78.9 |

21.1 |

15.1 |

6.0 |

|

2014 |

77.4 |

22.6 |

13.9 |

8.7 |

|

2015 |

78.4 |

21.6 |

15.6 |

6.0 |

|

2016 |

76.3 |

23.6 |

18.2 |

5.4 |

|

2017 |

73.7 |

26.3 |

16.4 |

9.9 |

|

2018 |

75.7 |

24.3 |

17.6 |

6.7 |

|

2019 |

77.2 |

22.8 |

14.8 |

8.0 |

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends. Department of Health, Western Australia (and previous years’ reports)

* Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

Note: This is trend data presented by the Department of Health. Data in all years has been standardised by weighting them to the 2011 estimated resident population.

Proportion of children and young people aged 5 to 15 years by BMI categories, per cent, WA, 2004 to 2019

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends. Department of Health, Western Australia (and previous years’ reports)

However, age differences exist. In particular, a greater proportion of children aged five to nine years are consistently categorised as obese compared to children and young people aged 10 to 15 years (subject to the margin of error).

|

Overweight |

Obese |

Total |

||||

|

5 to 9 years |

10 to 15 years |

5 to 9 years |

10 to 15 years |

5 to 9 years |

10 to 15 years |

|

|

2012 |

13.5 |

15.5 |

9.4 |

5.9 |

22.9 |

21.4 |

|

2013 |

16.1 |

14.4 |

8.6* |

4.1* |

24.7 |

18.5 |

|

2014 |

15.6 |

12.6 |

15.5 |

3.7* |

31.1 |

16.3 |

|

2015 |

14.9 |

16.2 |

7.8* |

4.6* |

22.7 |

20.8 |

|

2016 |

17.0 |

19.1 |

7.3* |

4.0* |

24.3 |

23.1 |

|

2017 |

16.4 |

16.2 |

14.7 |

6.3* |

31.1 |

22.5 |

|

2018 |

17.9 |

17.2 |

8.5* |

5.2* |

26.4 |

22.4 |

|

2019 |

13.1 |

16.0 |

13.6* |

3.7* |

26.7 |

19.7 |

Source: Dombrovskaya M et al 2020, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2019, Overview and Trends. Department of Health, Western Australia (and previous years’ reports)

* Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

The WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System does not report on the proportion of children who are determined to be underweight based on the BMI calculation.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics National Health Survey collects data on BMI categories for children and young people across Australia. The 2017–18 survey provides data for WA, however it has a high margin of error and has not been reproduced here.

Consistent with the WA Department of Health surveillance system, this survey reports that a higher proportion of Australian children aged 8 to 11 years are overweight or obese than young people aged 12 to 15 years.

|

Australia |

|||

|

5 to 7 years |

8 to 11 years |

12 to 15 years |

|

|

Underweight |

7.5 |

9.5 |

7.4 |

|

Normal weight |

65.1 |

65.4 |

71.6 |

|

Overweight |

17.4 |

17.7 |

14.8 |

|

Obese |

10.3 |

6.9 |

6.7 |

|

Overweight/Obese |

27.5 |

25.2 |

20.8 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Health Survey 2017–18, Table 16.3 Children's Body Mass Index, proportion of persons

In the WA Health and Wellbeing survey, over the last six years a higher proportion of female children than male children aged five to 15 years were reported as overweight or obese, however the differences are not statistically significant.15

|

Male |

Female |

|||||

|

Not overweight |

Overweight |

Obese |

Not overweight |

Overweight |

Obese |

|

|

2012 |

76.9 |

14.4 |

8.7 |

78.9 |

15.0 |

6.0 |

|

2013 |

74.8 |

16.6 |

8.7* |

83.0 |

13.7 |

3.3* |

|

2014 |

78.6 |

13.4 |

8.0* |

75.6 |

14.5 |

10.0* |

|

2015 |

78.9 |

14.9 |

6.2* |

77.7 |

16.3 |

5.9* |

|

2016 |

77.8 |

16.5 |

5.7* |

74.9 |

19.8 |

5.3* |

|

2017 |

77.0 |

13.2 |

9.8 |

69.9 |

19.5 |

10.6 |

|

2018 |

81.5 |

12.1 |

6.4* |

69.8 |

23.2 |

7.1* |

|

2019 |

75.0 |

15.9 |

9.0* |

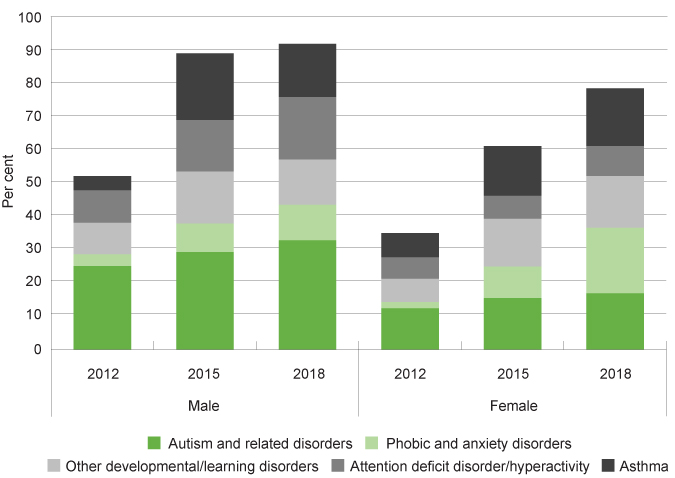

79.5 |