Developmental screening

There is a strong relationship between a child’s early health and their wellbeing later in life. As children grow older the developmental pathways initiated in early childhood become more difficult to change. Therefore, intervention when children are young is the most effective time to make a difference.

It should be noted that screening is only a first step and not an outcome in itself. If a child is identified as having a potential health or developmental issue it is essential that they are referred for further diagnosis and, if necessary, they receive appropriate treatment and services.

Last updated August 2021

Some data is available on whether WA children aged 6 to 11 years are being screened for health and developmental issues.

Overview

Children in WA can access five child health checks between birth and two years, plus a School Entry Health Assessment in the first year of school attendance. This indicator considers the School Entry Health Assessment which is conducted in Kindergarten for most WA children.

For information on the child health checks from birth to two years refer to the Developmental screening indicator in the 0 to 5 years age group.

In the 2019 school year, around 96.0 per cent of Kindergarten children across WA received a School Entry Health Assessment.

Areas of concern

The proportion of children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment in the Pilbara (93.2%) and the Kimberley (90.9%) is lower than in all other regions in WA and metropolitan Perth.

There is no reliable data available on the proportion of Aboriginal children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment in remote and regional WA.

There is no data on the proportion of eligible children in out-of-home care who received the School Entry Health Assessment or equivalent health and development check. In 2015, only 53.1 per cent of children entering out-of-home care had an initial medical examination.1

Other measures

Oral health is also an important measure of child wellbeing, as oral disease can cause pain, discomfort as well an increased risk of chronic disease in later life.2 While oral health is important for children and young people, it is not included in the Indicators of wellbeing.

The child health and development checks include an oral check and therefore are the primary mechanism for identifying issues with oral health. If children are attending the full complement of health checks, oral health issues should be identified.

For more information about oral health in Australia refer to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Oral health and dental care in Australia web report.

Endnotes

- Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015-16 Baseline Indicator Report, p. 5.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Oral health and dental care in Australia, AIHW.

Last updated August 2021

Optimising a child’s chance to have a healthy and productive life requires a holistic approach which includes a safe and nurturing home and community environment, access to appropriate health and family services and early identification of risk factors and developmental issues.1,2 Health and development screening is a key component used within Australia to assist in early identification of health and developmental issues.

Child development health checks are a critical service that provide an entry point to other child health services. When they are not performed, developmental and health problems may not be detected and intervention may be delayed.

The School Entry Health Assessment is conducted in Kindergarten, or occasionally Pre-primary, by child health nurses and includes developmental, vision, hearing, growth and oral health assessments. There is also scope for the nurse to consider using the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ3/ASQ:SE2TM) if developmental issues are indicated.3

If a child is identified as requiring follow-up, the parent or guardian is contacted and referred to the appropriate services. If the parent or carer of a child does not act on the referral, it is recommended the child health nurse follow up with the school and consider other support services for the family.4

The School Entry Health Assessments for children and young people in the Perth metropolitan area5 are managed by the Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Community Health Service, while assessments in regional and remote WA are managed by the Department of Health, WA Country Health Service.

In metropolitan Perth the School Entry Health Assessment completion rate has consistently exceeded the target rate of 90 per cent. In the 2019 school year, 96.0 per cent of metropolitan Kindergarten children received a School Entry Health Assessment.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Proportion of children |

92.1 |

96.0 |

94.8 |

94.3 |

96.0 |

96.0 |

Source: Child and Adolescent Community Health Annual Reports, 2014–20

In the 2010 Auditor General’s report on child health checks it was noted that 84 per cent of children in the metropolitan area received the School Entry Health Assessment in 2009.6 The current screening rates therefore represent a significant improvement since 2009.

In 2019 in regional and remote WA, 96.3 per cent of children received a School Entry Health Assessment.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Proportion of children |

97.2 |

95.7 |

96.9 |

92.4 |

92.6 |

96.3 |

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

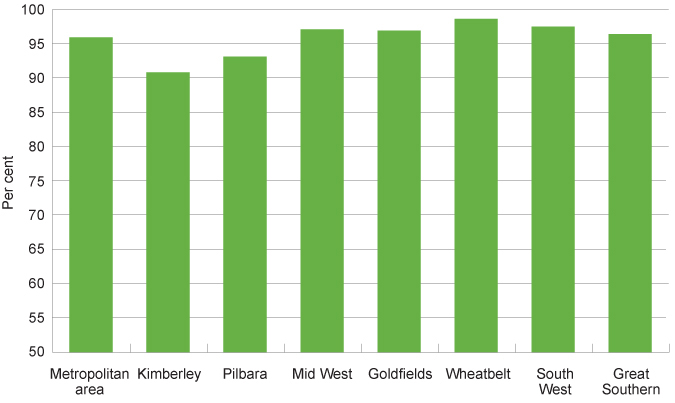

There was some variation across the state. In 2019, the number of children receiving a School Entry Health Assessment was lower in the Kimberley and Pilbara than other WA regions, including metropolitan Perth.

|

Per cent |

|

|

Kimberley |

90.9 |

|

Pilbara |

93.2 |

|

Mid West |

97.2 |

|

Goldfields |

97.0 |

|

Wheatbelt |

98.7 |

|

South West |

97.6 |

|

Great Southern |

96.5 |

|

Total |

96.3 |

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of eligible children receiving a School Entry Health Assessment by region, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Child and Adolescent Community Health Annual Report, 2019–20 and custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

There is no data available that reports the proportion of Aboriginal children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment in regional and remote WA. The Kimberley and the Pilbara have the highest proportion of Aboriginal children across WA,7 therefore it is likely that a lower proportion of Aboriginal children than non-Aboriginal children are receiving these checks.

For a variety of reasons, including higher poverty rates8 and a larger proportion of Aboriginal children living in regional and remote locations, Aboriginal children are at a greater risk of experiencing developmental issues in childhood and also in adulthood.9 It is therefore critical that they are assessed for health and developmental issues in a timely manner. To monitor this, it is essential that data is collected and made available on the proportion of Aboriginal children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment and other health and developmental checks.

It should also be noted that receiving the School Entry Health Assessment is only a first step – if a child is identified as having a potential health or developmental issue it is critical that they are referred for further diagnosis and, if necessary, they receive appropriate treatment and services.

In the 2018 school year, 15 per cent of children in the Perth metropolitan area receiving a School Entry Health Assessment were referred to other services.10

Referrals in the Perth metropolitan area are tracked electronically within the Child Development Information System (CDIS). The CDIS also records if referrals are declined by the parent/carer, which provides the child health nurse with an opportunity to take further action, where appropriate.

The CDIS record enables community health nurses to monitor individual outcomes following a referral to Child Development Services (CDS). These can be centrally reported and monitored. Where children are referred to external health care providers (including GPs and medical specialists) outcomes data cannot be centrally monitored. In 2018, 72 per cent of referrals from metropolitan School Health Services were to external providers.

In 2010 the Auditor General noted that child health checks were the main referral point to CDS. The Auditor General also noted that CDS have historically had significant waitlists for therapy and treatment of identified developmental delays.11 In 2016–17 the Child and Adolescent Community Health Service redesigned the Perth metropolitan CDS. In that year, waiting times for CDS allied health services were approximately three to five months, which represented a 50 per cent reduction in comparison with 2015–16.12 In 2017–18 median waiting times were between one and six months.13

For children in remote and regional WA, no data is currently available on the overall proportion of children referred to other services or on the result of referrals from the School Entry Health Assessment. This is expected to improve with the recent implementation of a single data collection system across the WA Country Health Service.

Children in the youth justice system

It is increasingly recognised that children in the youth justice system have a higher likelihood of having health issues than the general population, including mental health issues and cognitive disability.14 Yet, children and young people entering the youth justice system are not necessarily being screened for health and developmental issues upon entry to the system.15,16

The Banksia Hill Detention Centre is the only facility in WA for the detention of children and young people 10 to 17 years of age who have been remanded or sentenced to custody. During 2019–20, approximately 107 children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years were held in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre in WA on an average day.17

In 2016, a Telethon Kids Institute study found that 89 per cent of the study participants at Banksia Hill had at least one domain of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, and 36 per cent were diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). This study also found a greater prevalence of FASD among the Aboriginal children and young people at Banksia Hill.18

The majority of these children and young people had not been previously diagnosed either through the school system, child protection system or the justice system.19 This highlights a critical need for improved health assessment and diagnosis processes in the juvenile justice system and other service systems more broadly.

Children and young people entering youth detention have the right to be assessed for physical or intellectual disability, mental health issues, learning difficulties or any other vulnerabilities, and where issues are identified, they should be provided with the appropriate care and support.

Endnotes

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council 2011, National Framework for Universal Child and Family Health Services, Australian Government.

- Moore TG et al 2017, The First 1000 Days: An Evidence Paper – Summary, Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Child and Adolescent Health Services, Community Health Clinical Nursing Manual: Universal Contact School Entry Health Assessment, WA Department of Health.

- Ibid.

- A number of outer metropolitan area post codes classified as Inner Regional (ABS Remoteness Index) fall within the Child and Adolescent Health Services Community Health catchment. These include Bullsbrook, Childlow, Chittering, Gidgegannup, Jarrahdale, Two Rocks and Waroona. Services provided to children and families living in these areas are included in the above. All other metropolitan postal codes are classified as Major Cities.

- Auditor General for WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Office of Auditor General WA, p. 17.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2016 Census Community Profiles, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Profile, ABS.

- Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) 2018, Poverty in Australia 2018, ACOSS and University of New South Wales, p. 65.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015, Australia’s Welfare: 2015 – Snapshot: Indigenous Children, AIHW.

- Information provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People by the Department of Health Child and Adolescent Community Health service [unpublished].

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Report 11, November 2010, p. 14-15.

- Child and Adolescent Health Service 2017, 2016–17 Annual Report, WA Department of Health.

- Child and Adolescent Health Service 2018, 2017–18 Annual Report, WA Department of Health.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, National data on the health of justice-involved young people: a feasibility study 2016–17, Cat no JUV 125, AIHW.

- The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2011, The health and well-being of incarcerated adolescents, RACP.

- Bower C et al 2018, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

- WA Department of Justice 2020, Annual Report: 2019–20, WA Government, p. 34.

- Bower C et al 2018, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

- Ibid.

Last updated August 2021

At 30 June 2021 there were approximately 1,906 children aged six to 11 years in out-of-home care in WA, more than half (57.0%) of whom were Aboriginal.1

Children in care are more likely than the general population to have poor physical, mental and developmental health.2 At the same time, children in out-of-home care often receive inadequate health care due, in part, to placement instability combined with limited coordination and information-sharing between service providers.3

Standard five of the National Standards for Children in out-of-home care states that children and young people should have their physical, developmental, psychosocial and mental health needs assessed and attended to in a timely way.4 The Royal Australian College of Physicians recommends that children in care receive a comprehensive assessment of their health within 30 days of placement.5

The WA Department of Communities casework practice manual requires that all children entering the WA out-of-home care system receive an initial medical assessment by a general practitioner or a health professional within 20 days and that they have an ongoing annual health assessment.6 The health provider is nominated by the Department of Communities and can include an Aboriginal Medical Service, general practitioner or a community health nurse. The Department of Health (Child and Adolescent Community Health Service) monitors the health and development assessments of children in care conducted by metropolitan community health nurses.

In 2016, the WA Department of Child Protection (now Department of Communities) published the Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015-16 Baseline Indicator Report. The outcomes framework identified two indicators related to reviewing the physical health of children in out-of-home care.

The first indicator was the ‘proportion of children who had an initial medical examination when entering out-of-home care’. In 2015, 53.1 per cent of children entering out-of-home care had an initial medical examination.7

The second indicator was the ‘proportion of children who have had an annual health check of their physical development'. In this report they noted that there were limitations in data accuracy which prevented reporting on this indicator in 2015–16, however data would be reported in 2016–17.8

No more recent data has been reported by the Department of Communities as at publication date.

Within an effective system it is critical to ensure transparency of practice. A key recommendation of numerous reviews has been to improve transparency of child protection processes and practices.9

The low proportion of children provided with an initial medical examination in 2015 and lack of publicly available data on whether all children in care are receiving these essential checks needs to be urgently addressed.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2021, Custom report provided by Department of Communities, WA Government [unpublished].

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2006, Health of children in “out- of- home” care, RACP.

- Australian Department of Health 2011, National Clinical Assessment Framework for children and young people in out-of-home care, Australian Government.

- Department of Social Services 2011, An outline of the National Standards for out-of-home care, Australian Government.

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2006, Health of children in “out- of- home” care, RACP.

- Department of Child Protection and Family Support (Communities), Casework Practice Manual: Health care Planning, WA Government.

- Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015-16 Baseline Indicator Report, p. 5.

- Ibid, p. 10.

- Bessant J 2016, Transparency and “uncomfortable knowledge” in child protection, Policy Studies, Vol 37, No 2.

Last updated August 2021

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates 22,400 WA children (11.5%) aged six to 11 years had reported disability in 2018.1

Childhood health and development checks can often identify children with potential disability or developmental issues. A child who presents with possible disability through this process will be referred to Child Development Services for assessment.

All families are offered a School Entry Health Assessment, but many children with disabilities have already been identified and are already engaged with secondary or tertiary level health services. Therefore, parents of children attending Education Support Schools are more inclined to decline the School Entry Health Assessment.

The Department of Education assesses a child’s disability and learning needs to determine education adjustments that may be required. For more information on this process refer to the Disability Standards for Education 2005.

There is no data on the proportion of WA children with disability who receive a School Entry Health Assessment or other health and developmental checks.

Endnotes

- Data is sourced from a custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the Australian Bureau of Statistics based on the 2018 Disability, Ageing and Carers survey. The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities’. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018, Glossary.

Last updated August 2021

The health of children is affected by a number of intersecting elements including socio-economic factors such as family education, employment and income, and environmental factors, such as availability of services within communities. In particular, poverty is specifically linked with poorer health and wellbeing outcomes.1

The current rate of children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment is encouraging and suggests a high proportion of WA children are being checked for health and developmental issues as they enter Kindergarten or Pre-primary.

However, there is no centralised information available on whether metropolitan children recommended for referral to external providers have received appropriate services for any issues identified. In 2018, external providers represent the bulk of referrals (72%) for the School Entry Health Assessment in the metropolitan area.2 There is currently no obligation on external providers to advise the Department of Health of referral outcomes.

There are also regional differences with a lower proportion of children in the Pilbara and the Kimberley receiving the School Entry Health Assessment. This will be disproportionately impacting Aboriginal children, although there is no robust data of the proportion of Aboriginal children attending these assessments compared to non-Aboriginal children.

Aboriginal children are at greater risk of having physical health issues over their lifetime, including obesity, which contributes to a higher risk of chronic disease. Life expectancy is 8.6 years lower for Aboriginal men, and 7.8 years lower for Aboriginal women than non-Aboriginal WA adults.3 The difference in life expectancy is largely due to a higher incidence of chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes and various cancers.4

The health of Aboriginal children is influenced by a number of factors including low birth weight (related to maternal smoking during pregnancy), inadequate consumption of fresh vegetables and social determinants such as poverty and housing. Furthermore, an essential factor impacting Aboriginal children’s health and wellbeing is the availability of culturally appropriate health services.5 Evidence suggests that universal mainstream child health services are under-used by many within the Aboriginal population.6

A critical component of improving Aboriginal people’s health and wellbeing over the longer term is to ensure Aboriginal children are assessed for health and development issues in a timely manner, and where necessary referred to high quality culturally safe services. Collecting and reporting data on the number and proportion of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment for each region is a critical component of improving this service.

The School Entry Health Assessment includes consideration of other developmental issues based on parent’s identification of any concerns and it can include screening for social-emotional issues using the Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ3/ASQ:SE2TM).7 However, this is not a mandatory component of the check. There are no other formal checks for cognitive or behavioural issues in the School Entry Health Assessment.

In the Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia, the WA State Coroner noted that a number of the children and young people were likely to have been on the spectrum for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), but that none had been formally diagnosed.8

While FASD is a complex condition and difficult to diagnose,9 preliminary screening for FASD and other cognitive or behavioural issues should occur as part of the universal child health checks and at key points across a child's life (e.g. pre-kindy, school entry). Any indication of issues through these screening checks should trigger appropriate referrals and be linked to clear supports and services.

There should be a sustained effort to increase the number of children, in particular Aboriginal children, receiving the School Entry Health Assessment and other child health checks in regional and remote areas.

Data gaps

No centralised data is available on whether the children referred to external providers as a result of the School Entry Health Assessment have received further support and care. This information is essential to service planning and monitoring.

No data is available on the proportion of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children receiving the School Entry Health Assessment in remote and regional Australia. Aboriginal children are at a higher risk of experiencing developmental issues in childhood and also in adulthood.10 It is therefore critical that data is captured to report whether Aboriginal children are receiving the School Entry Health Assessment.

No data is available on the number and proportion of WA children in care who have received the School Entry Health Assessment or alternative medical examination or other developmental checks, despite there being a Departmental requirement for an initial medical examination and annual health assessments.11 Children in care are more likely than the general population to have poor physical, mental and developmental health,12 therefore it is essential that they receive appropriate health and developmental checks on entry into care and on a regular basis thereafter.

The lack of data regarding provision of health and development checks for these vulnerable children needs to be urgently addressed.

Endnotes

- Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) 2008, ARACY Report Card, Technical Report: The Wellbeing of Young Australians, ARACY.

- Information provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People by the WA Department of Health Child and Adolescent Community Health service [unpublished].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Life Tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2010, Contribution of chronic disease to the gap in adult mortality between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and other Australians, Cat No IHW 48, AIHW.

- Zubrick SR et al 2004, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Health of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, pp. 287-288.

- WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Service 2018, Community Health Clinical Nursing Manual: Aboriginal Child Health Policy, WA Government.

- Child and Adolescent Health Services, Community Health Clinical Health Nursing Manual: Universal Contact School Entry Health Assessment, WA Department of Health.

- WA State Coroner 2019, Inquest into the deaths of: Thirteen children and young persons in the Kimberley region, Western Australia, WA Government, p. 256.

- Bower C and Elliott EJ 2016, on behalf of the Steering Group, Report to the Australian Government Department of Health, Australian Guide to the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), Telethon Kids Institute and University of Sydney.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015, Australia’s Welfare: 2015 – Snapshot: Indigenous Children, AIHW.

- Department of Child Protection and Family Support (Communities), Casework Practice Manual: Health care Planning, WA Government.

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2006, Health of children in “out- of- home” care, RACP.

For more information on development screening refer to the following resources:

- Auditor General for WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Office of Auditor General WA.

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council 2011, National Framework for Universal Child and Family Health Services, Australian Government.

- Department of Health 2018, National Framework for Universal Child and Family Health Services: 3.8.1 Developmental surveillance and health monitoring, Australian Government.

- McLean K et al 2014, Screening and surveillance in early childhood health: Rapid review of evidence for effectiveness and efficiency of models; Murdoch Children Research Institute.

- Webster S et al 2012, Children and young people in out-of-home care: Improving access to primary care, Australian Family Physician, Vol 41, No 10.

- Wise S 2013, Improving the early life outcomes of Indigenous children: implementing early childhood development at the local level, Closing the Gap Clearing House, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).