Safe in the home

Feeling safe and being safe at home is critical for young people’s healthy development. A safe and supportive family provides a sense of security, fosters self-esteem and responds appropriately to young people’s needs.1

Young people who experience family violence, abuse and neglect are more likely to have poor outcomes including poor physical health, learning and developmental difficulties, higher rates of alcohol and substance abuse, mental illness, criminality, homelessness, later parenting issues and suicide.2

Last updated August 2020

Some data is available on whether WA young people aged 12 to 17 years feel safe and are safe in their homes.

Overview

This indicator considers some key measures on whether young people feel safe and are safe at home. This includes data on family and domestic violence and the child protection system in WA.

Areas of concern

In the Speaking Out Survey 2019, a significant proportion (37.2%) of young people aged 12 to 17 years said they do not always feel safe at home.

There is limited data on the prevalence of abuse and neglect impacting young people in WA. It is expected that this this gap will be at least partially addressed by the Australian Child Maltreatment Study funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

In 2017, 1,674 incidents (6.3% of all incidents) were recorded by WA Police with WA children and young people aged 10 to 17 years as victims of family violence.

At 30 June 2019, the rate of WA Aboriginal children and young people being in out-of-home care was 64.1 per 1,000 children, 17 times the rate for WA non-Aboriginal children (3.8 per 1,000).

Other measures

Injuries and poisoning are major causes of hospitalisation for children and young people in Australia. A measure on child deaths or injuries has not been selected for the Indicators of wellbeing as data is regularly compiled by Kidsafe WA and the WA Ombudsman.

For information on child deaths refer to the Ombudsman’s annual Child Death Review. For information on injuries for children refer to Kidsafe WA Childhood Injury Bulletins & Reports. For information on young people aged 12 to 17 years engaging in self-harm refer to the Mental health indicator.

Last updated August 2020

Young people in this age group experience various physical, cognitive and emotional changes related to the transition to adulthood. Strong and positive relationships in the home are protective against a range of behaviours that can affect young people during adolescence, including mental health issues, drug and alcohol misuse and unsafe sexual activity.1,2 Feeling safe and supported in the home is also essential to allow young people to develop confidence and independence while being protected from harm.

When young people feel unsafe in the home they are more likely to have poor physical and mental health, poor academic outcomes and are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviours.3,4

While some young people do not feel safe at home because they are experiencing abuse and neglect, other young people may not feel safe at home due to parental conflict, sibling bullying,5 being left home alone,6 parental rejection of their lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or intersex (LGBTI7) status and/or excessive parental control being exerted over their lives.8,9,10

Families can often experience conflict during the adolescent years and it can be challenging for parents and young people to successfully manage and resolve these conflicts. In some circumstances, young people feel so unsafe or unsupported at home that they may leave home, which can result in them becoming homeless.

In WA in 2018–19, 768 young people aged 15 to 17 years presented alone to homelessness services.11 In a survey of homeless young people in Australia, more than one-half (56.0%) had left home because of violence between parents or guardians on at least one occasion.12

Other research suggests that some young people do not leave home, but continue to feel unsafe and unsupported in their home. This can include young women from some culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities whose families may limit their ability to participate in the Australian community in the way they would like.13

Young people may also not feel safe at home due to negative online experiences including cyberbullying. This is discussed in the Safe in the community indicator.

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about feeling safe at home.

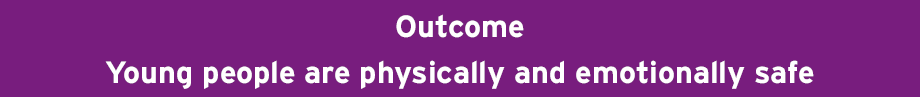

For students in Year 7 to Year 12, 61.2 per cent reported they felt safe at home all the time and 29.0 per cent felt safe most of the time, while 3.3 per cent of students reported feeling safe at home only a little bit of the time or never.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

All the time |

68.4 |

54.2 |

60.6 |

61.9 |

68.5 |

61.2 |

|

Most of the time |

24.0 |

34.2 |

29.9 |

26.1 |

23.8 |

29.0 |

|

Sometimes |

3.0 |

6.9 |

4.7 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

4.9 |

|

A little bit of the time |

2.5 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

|

Never |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.6 |

N/A |

0.9 |

|

Prefer not to say |

0.4 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

N/A |

0.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

N/A – Cells are suppressed where the number of students providing data for that response was less than 5.

Just over one-half (54.2%) of female Year 7 to Year 12 students feel safe at home all the time, while one-third (34.2%) feel safe at home most of the time. This represents a significantly lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students who report feeling safe all the time (54.2% compared to 68.4%). This also represents a significant decline from the proportion of Year 4 to Year 6 female students who feel safe at home all the time (65.5%).14

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting they feel safe at home all of the time, most of the time, sometimes, a little bit of the time, never by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A significantly higher proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students in remote areas compared to metropolitan and regional areas feel safe at home all the time (68.5% compared to 60.6% and 61.9%).

A marginally higher proportion of Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students than non-Aboriginal students reported feeling safe at home all the time (64.2% compared to 61.0%). These differences are not statistically significant.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

All the time |

64.2 |

61.0 |

|

Most of the time |

24.8 |

29.3 |

|

Sometimes |

5.3 |

4.9 |

|

A little bit of the time |

1.8 |

2.4 |

|

Never |

1.2 |

0.9 |

|

Prefer not to say |

N/A |

0.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

N/A – Cells are suppressed where the number of students providing data for that response was less than 5.

The survey also included a question asking Year 7 to Year 12 students whether they had ever stayed away from home overnight because of a problem.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

73.1 |

58.3 |

67.7 |

56.3 |

56.0 |

65.5 |

|

Yes |

23.7 |

36.3 |

28.3 |

38.1 |

39.0 |

30.3 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.2 |

5.4 |

3.9 |

5.5 |

5.0 |

4.2 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Thirty per cent of Year 7 to 12 students (30.3%) reported they had ever stayed away from home overnight because of a problem. A significantly higher proportion of female than male students reported they had ever done this (36.3% female compared to 23.7% male).

A lower proportion of students in the metropolitan area than non-metropolitan areas had stayed away from home overnight because of a problem (28.3% compared to 38.1% regional and 39.0% remote).

Among the students in Year 7 to Year 12 who reported they had stayed away from home overnight, 35.6 per cent reported they had done this once and 31.7 per cent reported they had done this more than once in the last 12 months. A significantly higher proportion of female students than male students reported they did this more than once in the last 12 months (39.1% female compared to 22.0% male).15

Students were also asked whether they worried about family members being harmed or harming someone else. The majority of students in Year 7 to Year 12 did not worry that someone in their home or family will hurt themselves (63.4%) or hurt somebody else (67.0%). Conversely, 20.0 per cent of students worried a lot or somewhat that someone in their house will hurt themselves and 18.4 per cent worried a lot or somewhat that someone in their home or family may hurt someone else.

|

Hurt themselves |

Hurt somebody |

|||||

|

Male |

Female |

All |

Male |

Female |

All |

|

|

Not at all |

68.0 |

59.3 |

63.4 |

70.2 |

63.9 |

67.0 |

|

A little |

16.2 |

16.8 |

16.6 |

14.2 |

15.1 |

14.6 |

|

Somewhat |

8.5 |

12.2 |

10.3 |

8.7 |

10.2 |

9.6 |

|

A lot |

7.3 |

11.8 |

9.7 |

6.9 |

10.7 |

8.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A significantly lower proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 female students than male students never worried about someone in their family hurting themselves (59.3% compared to 68.0%), while 11.8 per cent of female students worried a lot about this (compared to 7.3% of male students).

There were no significant differences in responses between geographic locations or Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students for either question.16

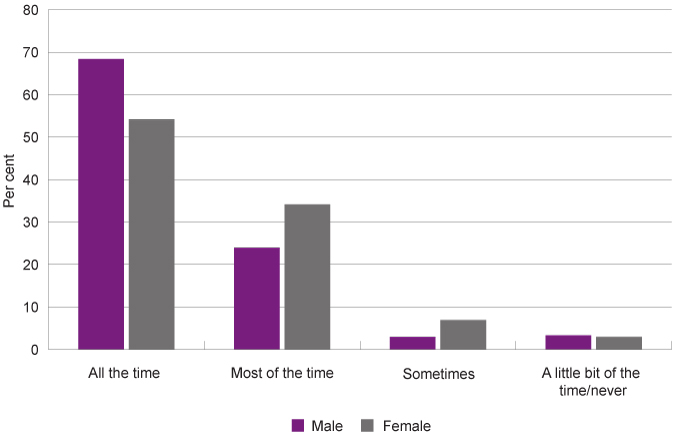

Students were also asked whether they worried that someone in their home or family will be fighting. A significantly lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students never worried about this (40.1% compared to 55.8%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Not at all |

55.8 |

40.1 |

47.2 |

50.4 |

50.9 |

47.8 |

|

A little |

25.9 |

27.4 |

27.3 |

22.3 |

29.3 |

26.7 |

|

Somewhat |

10.7 |

18.3 |

14.7 |

15.0 |

8.2 |

14.4 |

|

A lot |

7.5 |

14.2 |

10.8 |

12.4 |

11.5 |

11.0 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting they worry a lot, somewhat, a little or not at all that someone in their home or family will be fighting by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Almost one-third (32.5%) of female students worried somewhat or a lot about someone in their home or family fighting, this increased from 19.6 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 female students (male Year 7 to Year 12: 18.2%, male Year 4 to Year 6: 17.4%).17

There were no significant differences reported between geographic locations or Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students.

These perceptions of safety in the home provide a critical insight into young people’s views and concerns, however more research is required to determine what drives these perceptions and how they relate to experiences of harm.

In the annual Mission Australia 2019 Youth Survey, 25,126 Australian young people aged 15 to 19 years responded to questions across a broad range of topics including education and employment, participation in community activities, general wellbeing, values and concerns and preferred sources of support.

The 2019 sample included 2,766 young people from WA.18 One-half of WA respondents (50.3%) were male and 45.8 per cent were female with remainder choosing either ‘other or ‘preferred not to say’. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people comprised 5.9 per cent of WA respondents.19

The 2019 survey asked respondents about issues that concern them the most, including family conflict and family and domestic violence. The question did not specify whether participants were concerned about family conflict and/or violence in their own home or concerned more broadly about its occurrence in society.

|

Australia |

WA |

||

|

Family conflict |

Not at all concerned |

44.8 |

45.7 |

|

Slightly concerned |

19.9 |

18.5 |

|

|

Somewhat concerned |

17.1 |

16.7 |

|

|

Very concerned |

11.1 |

11.6 |

|

|

Extremely concerned |

7.1 |

7.5 |

|

|

Family and domestic violence |

Not at all concerned |

71.1 |

70.8 |

|

Slightly concerned |

11.0 |

9.8 |

|

|

Somewhat concerned |

8.7 |

8.5 |

|

|

Very concerned |

5.0 |

5.5 |

|

|

Extremely concerned |

4.2 |

5.4 |

|

Source: Mission Australia, Youth Survey Report 2019

The results showed that 19.1 per cent of WA participants were very or extremely concerned about family conflict and 10.9 per cent were very or extremely concerned about family and domestic violence. WA participants were slightly more concerned about both these issues than Australian respondents overall.

|

Family conflict |

Family and domestic violence |

|||

|

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

|

|

Extremely concerned |

10.6 |

3.9 |

7.1 |

2.9 |

|

Very concerned |

15.4 |

8.5 |

6.7 |

4.5 |

|

Total |

26.0 |

12.4 |

13.8 |

7.4 |

Source: Mission Australia, Youth Survey Report 2019

Female respondents were significantly more likely than male respondents to report feeling very or extremely concerned about family conflict (26.0% female compared to 12.4% male) and family and domestic violence (13.8% female compared to 7.4% male).20

Endnotes

- Robinson E 2006, Young people and their parents: Supporting families through changes that occur in adolescence, Australian Family Relationships Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Moretti MM 2004, Adolescent-parent attachment: Bonds that support healthy development, Paediatrics Child Health, Vol 9, No 8.

- Kaspiew R et al 2017, Domestic and family violence and parenting: Mixed method insights into impact and support needs: Final report, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), p. 23.

- Lepisto S et al 2011, Witnessing and experiencing domestic violence: a descriptive study of adolescents, Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, Vol 25.

- Dantchev S and Wolke D 2019, Trouble in the nest: Antecedents of sibling bullying victimization and perpetration, Developmental Psychology, Vol 55, No 5.

- Child Family Community Australia 2014, Leaving a child home alone: Considerations for parents and professionals, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- The Commissioner’s office uses the broad term LGBTI to inclusively refer to all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and have an intersex variation, as well as to represent other members of the communities that use different terms to describe their diverse sexuality and/or gender.

- National Youth Commission 2008, Australia’s Homeless Youth: a report of the National Youth Commission Inquiry into Youth Homelessness, Australian Government, p. 87-90.

- Durso LE and Gates GJ 2012, Serving Our Youth: Findings from a National Survey of Service Providers Working with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth who are Homeless or At Risk of Becoming Homeless, The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund, p. 4.

- Morton M et al 2018, Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Homelessness in the United States, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol 62.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, Specialist Homelessness Services Collection data cubes 2011–19, SHSC Demographics data cube, AIHW.

- MacKenzie D et al 2016, The Cost of Youth Homelessness in Australia: Research Briefing, Swinburne University of Technology et al, p. 2, 11.

- Child Family Community Australia (undated), Working with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) adolescents, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Carlisle E et al 2019, Youth Survey Report 2019, Mission Australia, p. 192. Note: Mission Australia recommend caution when interpreting and generalising the results for certain states or territories because of the small sample sizes and the imbalance between the number of young females and males participating in the survey.

- Ibid, p. 192.

- Ibid, p. 201-202.

Last updated August 2020

Every child or young person has a right to live free from violence, abuse and neglect.1 Most young people live in safe and supportive homes, however for some, home can be a place of conflict and distress as a result of family and domestic violence.

There is considerable overlap between children and young people being exposed to family and domestic violence and the child protection system. When a physical assault on a child or young person is reported, WA Police will make an assessment about whether to involve child protection authorities through a formal notification. The Department for Communities then determines whether a child/young person has suffered significant harm or is likely to suffer significant harm as a result of exposure to family and domestic violence.2

The next measure (Involved in the child protection system) records child protection service responses, including notifications, substantiations and children in care.

Family and domestic violence can be defined as ‘abusive behaviour in an intimate relationship or other type of family relationship where one person assumes a position of power over another and causes fear’.3 Abusive behaviour can include physical abuse or verbal, mental or emotional abuse or control. For young people it is often perpetrated by parents/carers, however, perpetrators can also be siblings and other family members such as step-fathers.

Living with family and domestic violence has short and long-term impacts on children and young people’s health and wellbeing. These include mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, difficulties at school, behavioural issues including violent behaviour, a higher likelihood of alcohol and drug misuse and greater risk of homelessness.4,5

Research also suggests that family and domestic violence can impact a parent’s ability to parent effectively.6

The causes of family and domestic violence are complex. Violence against women is linked to gender inequality reinforced through gender-based stereotypes. It is therefore critical to collect data on children and young people’s understanding of gender equality and violence against women.

The National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS) was conducted in 2017 and reported on young people’s (aged 16 to 24 years) attitudes to violence against women and gender equality.7

This survey found that most young people aged 16 to 24 years have a good knowledge of key aspects of violence against women, support gender equality, reject attitudes supportive of violence against women, and say they would act or like to act if they witnessed abuse or disrespect of women.9 However, there has been a decline in the number of Australian young people who recognise that men more often commit acts of domestic violence (71.0% in 2009, 75.0% in 2013 and only 60.0% in 2017).9

At the same time, over one in three (36.0%) young Australians stated they would not know where to get outside help for a domestic violence issue.10

Young people can also be perpetrators of family or domestic violence, either towards parents, siblings or intimate partners.11 Research suggests that most incidents of violence by young people in the home are committed by male adolescents against their mothers.12

In 2017, there were 600 incidents of family violence reported to WA Police where an offender was processed and was under 18 years of age. Of these, 69.2 per cent (415) were male young people.13 Data is not available on the age of the victim or whether the offender was in the family home or living independently.

For more information on adolescent violence in the home refer to:

Broadhead S and Francis R 2015, The Making of Good Men and Women, Summary Report: Responding to Youth Violence in the Home and its harmful impacts on families and communities in Western Australia, The Making of Good Men and Women Working Group.

Children and young people experiencing family and domestic violence as onlookers

Experiencing family and domestic violence involves children and young people not only being subject to family and domestic violence, but also witnessing family and domestic violence. Research has shown that the existence of violent behaviour in the home increases the likelihood of trauma and negative health and wellbeing outcomes.14,15,16

The WA Police Force (WA Police) collect data on whether children and young people are present at family violence-related incidents.17

Almost one-half of all family violence-related crime incidents reported, or becoming known, to WA Police between 2014 and 2017 had at least one child or young person present.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

|

Number of FV crime incidents |

21,641 |

26,913 |

31,316 |

28,716 |

|

Number of distinct FV crime incidents |

10,047 |

12,132 |

14,081 |

12,726 |

|

Proportion of incidents where |

46.4 |

45.1 |

45.0 |

44.3 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV incidents recorded in the Incident Management System (IMS) where at least one child was present, provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

* A child or young person aged 0 to 17 years.

Notes:

1. Crime incidents are recorded in the IMS where one or more valid offences are suspected to have occurred.

2. The family violence data is collected using the family violence (FV) flag in police systems. WA Police select the FV flag at the victim level when they have determined an offence or incident to be FV-related as defined by the relevant state legislation (Refer to ABS 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 – Explanatory Notes for more information).

3. Reporting on family violence by WA Police changed from 1 July 2017 due to changes in the legislation, for more information refer to: The Restraining Orders and Other Legislation Amendment (Family Violence) Bill 2016.

In 2017, at least one child or young person (aged 0 to 17 years) was present at 12,726 reported incidents of family violence across WA.

In the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey, 68.0 per cent of Australian women and 60.0 per cent of Australian men who had children in their care when they experienced intimate partner violence reported that the children had seen or heard the violence.18

The proportion of family violence crime incidents where a child was present varies between WA regions and districts with the Wheatbelt and South West districts having the highest proportions followed by the Metropolitan region.

|

Total incidents |

Total incidents |

Proportion of incidents |

|

|

Central Metropolitan |

4,018 |

1,746 |

43.5 |

|

North West Metropolitan |

4,249 |

2,064 |

48.6 |

|

South East Metropolitan |

4,539 |

2,162 |

47.6 |

|

South Metropolitan |

5,061 |

2,506 |

49.5 |

|

Metropolitan region |

17,867 |

8,478 |

47.5 |

|

Goldfields-Esperance |

1,254 |

469 |

37.4 |

|

Great Southern |

891 |

388 |

43.5 |

|

Kimberley |

3,427 |

1,017 |

29.7 |

|

Mid West-Gascoyne |

1,615 |

750 |

46.4 |

|

Pilbara |

1,720 |

643 |

37.4 |

|

South West |

1,336 |

667 |

49.9 |

|

Wheatbelt |

606 |

314 |

51.8 |

|

Regional WA total |

10,849 |

4,248 |

39.2 |

|

Total incidents |

28,716 |

12,726 |

44.3 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV crime incidents recorded in the Incident Management System (IMS), provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

Note: District is based on the location of the offence.

It should be noted that this data is the raw numbers of incidents without the commensurate population and therefore does not provide the rates of occurrence by area.

Children and young people experiencing family and domestic violence as direct victims

In 2017, 1,674 crime incidents19 (6.3% of all FV-related crime incidents) were reported, or became known, to WA Police with WA children and young people aged 10 to 17 years as one of the victims of family violence.

|

Number |

Per cent of total |

|

|

0 to 9 years |

562 |

2.1 |

|

10 to 17 years |

1,674 |

6.3 |

|

18 to 24 years |

4,395 |

16.5 |

|

25 to 44 years |

15,186 |

56.9 |

|

45 to 64 years |

5,709 |

21.4 |

|

65+ years |

766 |

2.9 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV crime incidents recorded in the Incident Management System (IMS), provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

Note: Values are a distinct count/ distinct per cent of incidents by demographics and offence location. As an incident may have multiple victims recorded across all demographics, the figures should not be summed.

It should be noted that WA Police are only able to record incidents detected and/or reported to them. There is clear evidence that family violence incidents are under-reported.20

In 2016, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) asked adult survey respondents to the Personal Safety Survey about experiences of childhood abuse (before 15 years of age). According to this survey, 13.0 per cent (2.5 million) of Australian adults have experienced childhood abuse. The majority of people experienced only one type of abuse; 5.8 per cent of respondents had experienced physical abuse, 5.0 per cent experienced sexual abuse and 2.7 per cent had experienced both.21

Based on this survey, an estimated one in 12 children and young people experienced physical abuse and one in 13 experienced sexual abuse before 15 years of age. Most adults who reported they were abused as children experienced their first incident before the age of 10.22

An estimated 81.0 per cent of people who experienced childhood physical abuse were first abused by a family member (78.0% were first abused by a parent). While, an estimated 51.0 per cent of people who experienced childhood sexual abuse were first abused by a non-familial known person (35.6% were abused by a family member).23

Analysis by the ABS showed that 71.0 per cent of people who experienced abuse as a child also experienced violence as an adult, compared to 33.0 per cent of those who did not experience childhood abuse.24

The ABS annually reports data on victims of family and domestic violence through the Recorded Crimes – Victims collection gathered from police agencies within each Australian jurisdiction.25

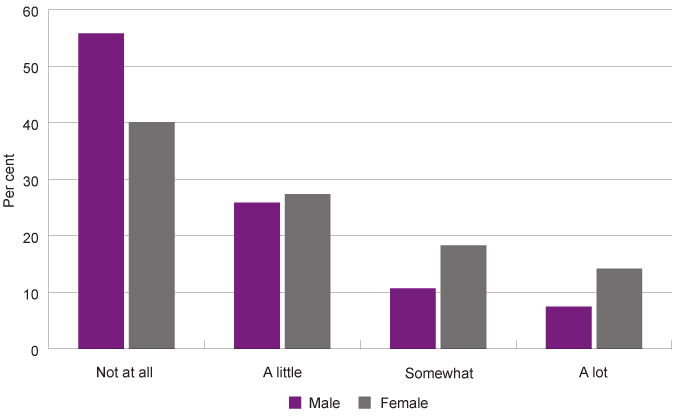

In 2019, 1,793 WA young people aged 15 to 19 years were reported as victims of family and domestic violence, physical and sexual assault.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

Per cent change since 2014 |

||

|

0 to 9 years* |

Physical assault |

218 |

274 |

314 |

342 |

342 |

351 |

61.8 |

|

Sexual assault |

140 |

126 |

139 |

192 |

134 |

142 |

- |

|

|

Total |

359 |

400 |

451 |

536 |

476 |

493 |

37.3 |

|

|

10 to 14 years* |

Physical assault |

383 |

469 |

559 |

538 |

531 |

556 |

45.2 |

|

Sexual assault |

130 |

89 |

113 |

152 |

140 |

168 |

29.2 |

|

|

Total |

513 |

558 |

670 |

690 |

671 |

724 |

41.1 |

|

|

15 to 19 years* |

Physical assault |

1,380 |

1,619 |

1,767 |

1,492 |

1,529 |

1,658 |

20.1 |

|

Sexual assault |

108 |

106 |

104 |

100 |

148 |

135 |

25.0 |

|

|

Total |

1,488 |

1,725 |

1,867 |

1,591 |

1,677 |

1,793 |

20.5 |

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 and 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault/sexual assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014–2019

* The age groupings are not equal – 0 to 9 years reports on 10 years, 10 to 14 years reports on 5 years and 15 to 19 years reports on 4 years.

Note: This data differs from the previous table as it includes only physical and sexual assault, compared to all incidents categorised as family and domestic violence.

Victims of family and domestic violence physical assault by age group, number, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014–2019

Since 2014, there has been an increase in the number of WA children and young people reported as victims of family and domestic violence physical assaults across all age groups, although for young people aged 15 to 19 years there was a decrease from 2016 to 2017.

Sexual assault that is family violence-related has increased by 29.2 per cent since 2014 for children and young people aged 10 to 14 years (from 130 children in 2014 to 168 in 2019) and by 25.0 per cent for young people aged 15 to 19 years (from 108 in 2014 to 135 victims in 2019).

It is not known whether these changes represent a change in the rate of occurrence or is due to other factors, including the population increasing or varying rates of reporting to WA Police.

Sexual assault is much less likely to be reported to the police for multiple reasons including the victim feeling shame, stigma, concern about whether they will be believed and sometimes fear of the perpetrator.26

It should be noted that if a sexual assault is reported for a child or young person under 18 years of age, WA Police must report this to the Department of Communities under the mandatory reporting regime.27

|

Physical assault |

Sexual assault |

|||

|

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

|

|

Male |

252 |

365 |

32 |

12 |

|

Female |

293 |

1,282 |

132 |

122 |

|

Total |

556 |

1,658 |

168 |

135 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 and 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault/sexual assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014–2019

Note: The ABS notes that totals may not sum due to perturbation.

WA young women aged 15 to 19 years are significantly more likely than young men to be the victims of physical assault as a result of family and domestic violence (1,282 female young people compared to 365 male young people). This may be due to young women aged 15 to 19 years being more likely than young men to be assaulted by intimate partners.28

Data from the ABS Personal Safety Survey shows that parents are the most common perpetrators of physical abuse of children younger than 15 years. Respondents to the survey were asked whether they experienced abuse before the age of 15 years. Of those who were victims of abuse before the age of 15 years, around 42.0 per cent were victims of physical abuse by a father or stepfather, and 22.0 per cent by a mother or stepmother.29 Approximately six per cent were abused by a sibling (which can include an adult sibling).30 A significant proportion were also abused by another ‘known person’.

Research indicates that women in regional, rural and remote areas are more likely to be victims of family and domestic violence.31,32 Across Australia, 23.0 per cent of women living outside major cities reported experiencing partner violence compared with 15.0 per cent living in major cities.33

There is no comparable research on the experiences of children and young people in regional and remote locations.

The cultural and social characteristics of regional and remote communities can influence the prevalence of domestic and family violence. Some of these factors include more traditional gender norms, a lack of access to appropriate services due to greater isolation and, for some communities, a greater focus on privacy and self-reliance.34

Data from the ABS 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) shows that there is a higher rate of family and domestic violence in Aboriginal families than non-Aboriginal families across Australia.35 This should be understood in the context of a history of colonisation, forced child removal, social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma.36

Aboriginal Australians are also more likely to have increased risk factors for family violence such as poor and overcrowded housing, higher levels of poverty, lower education and higher unemployment.37

The ABS collection on Recorded Crime – Victims does not report on data for Aboriginal peoples in WA as the data is not of sufficient quality.38 Furthermore, the NATSISS survey does not provide jurisdictional level data and no data on children and young people’s experiences of family and domestic violence.39

In the Longitudinal Study of Aboriginal Children participating families were asked about family violence, and families living in remote areas were significantly more likely to rate family violence as a big problem in the community.40

There is no data available on children and young people’s exposure to family and domestic violence in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, although research suggests that women in CALD communities are particularly vulnerable to experiencing domestic and family violence.41,42

There are many barriers that prevent CALD families from reporting violence and accessing services or support, including language difficulties, cultural differences regarding asking for help, and isolation due to separation from other family and friends.43

The experiences of CALD children and young people can differ to the experiences of Anglo‐Australian children because of trauma related to their pre‐migration and migration experiences, racism and discrimination, and the normalisation of certain cultural beliefs regarding gender equality.44

Considering their high risk of exposure, the lack of data and research with Aboriginal and CALD children and young people experiencing family and domestic violence is a significant gap.

Family violence-related homicide

In a small but critical number of cases family and domestic violence results in the tragic death of the victim or victims. Relative to other Australian jurisdictions for which data is available, a high number of WA people were murdered in a family and domestic violence incident in 2016 and 2018, however there were significantly fewer deaths in 2019.

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

NSW |

43 |

28 |

37 |

38 |

|

VIC |

40 |

35 |

33 |

36 |

|

QLD |

37 |

27 |

20 |

20 |

|

SA |

16 |

22 |

12 |

14 |

|

WA |

37 |

13 |

38 |

12 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019,Table 23 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related homicide, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014–2019

Furthermore, in 2019, no WA children and young people (aged 0 to 19 years) lost their lives due to family and domestic violence-related homicide (compared to 13 children and young people in 2018).45

From 30 June 2009 to 30 June 2019, family and domestic violence was the leading social and environmental factor that was associated with 72.0 per cent of investigable46 child deaths in WA.47

Across Australia, around 10.0 per cent of Australian homicide victims are children and young people aged 0 to 17 years. The majority are victims of filicide (murdered by their parents).48

Endnotes

- Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [website].

- Child abuse includes emotional abuse where young people are exposed to family and domestic violence as onlookers and they are deemed at risk of significant emotional/mental harm. When a physical assault on a child or young person is reported, the officer in charge will make an assessment about whether to involve child protection authorities. The Department for Communities then determines whether a child has suffered significant harm or is likely to suffer significant harm as a result of exposure to family and domestic violence. Significant harm or likelihood of significant harm may be caused by a single act of family and domestic violence or the cumulative impact of exposure over a period of time. Source: WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support (now Communities) 2014, Emotional abuse – Family and domestic violence policy, WA Government. If a sexual assault is reported for a child or young person under 18 years of age, the police officer in charge must report this to the Department of Communities under the mandatory reporting regime.

- QLD Department of Child Safety 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection – practice paper, QLD Government, p. 3.

- Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: CFCA Paper No. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 6

- Richards K 2011, Children’s exposure to domestic violence in Australia, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, No 419, Australian Institute of Criminology, p. 3.

- Kaspiew R et al 2017, Domestic and family violence and parenting: Mixed method insights into impact and support needs: Final report, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS).

- Politoff V et al 2019, Young Australians’ attitudes to violence against women and gender equality: Findings from the 2017 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) Insights, Issue 01/2019, ANROWS.

- Ibid, p. 6.

- Ibid, p. 21.

- Ibid, p. 20.

- Howard J 2015, Adolescent violence in the home: How is it different to adult family violence?, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Howard J 2011, Adolescent violence in the home – the missing link in family violence prevention and response, Australian domestic and family violence clearinghouse.

- Custom report of Family Violence crime incidents reported to WA Police provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by WA Police.

- Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: CFCA Paper No. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 6.

- Richards K 2011, Children’s exposure to domestic violence in Australia, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, No 419, Australian Institute of Criminology, p.1.

- QLD Department of Child Safety 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection – practice paper, QLD Government, p. 12-13.

- Inamendments made to the Restraining Orders Act 1997 (ROA) on 1 July 2017, the terminology used by the WA Police Force is ‘family violence’. The term domestic violence is no longer used within the policing context.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, Cat no FDV 3, AIHW, p. 71.

- Crime incidents of family and domestic violence are considered to be incidents that include a valid offence.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013, Defining the Data Challenge for Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, ABS.

- Ibid.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, Table 43.3 Experience of either physical or sexual abuse before the age of 15(a), ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, Media Release: Childhood abuse increases risk of violence in adulthood, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 Explanatory Notes, ABS.

- Australian Law Reform Commission 2010, The prevalence of sexual violence, Australian Government [website].

- WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support (now Communities) 2014, Policy on child sexual abuse, WA Government.

- Although there is no data explicitly reporting on intimate partner violence experienced by young people aged 15 to 19 years. Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019 reports that young women aged 15 to 24 years are significantly more likely to be hospitalised for family violence-related assaults than young men (Figure 3.7: Rate of hospitalisations for family or domestic violence assaults, by relationship to perpetrator, by age, by sex, 2016–17 (rate per 100,000)). Further, the ABS, Personal Safety Survey reports that women are three times more likely to have experienced violence by an intimate partner since the age of 15 year than men.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, Table 31.3 Experience of Abuse before the age of 15, Characteristics of abuse by sex of respondent, Proportion of persons, ABS.

- Ibid.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Mishra G et al 2014, Health and wellbeing of women aged 18 to 23 in 2013 and 1996: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, Report prepared for the Australian Government, Department of Health.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, Cat no FDV 3, AIHW, p. 101.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018, Cat No FDV 2, AIHW, p. 85.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018, Cat no FDV 2, AIHW, p. 88.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 Explanatory Notes, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, 4714.0 - National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014-15, ABS.

- Bennetts Kneebone L 2015, Partner violence in the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), Research summary: No.3/2015, Department of Social Services, p. 9.

- Campo M 2015, Children's exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- El Murr A 2018, Intimate partner violence in Australian refugee communities, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Queensland Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection: a practice paper, QLD Government, p. 19.

- InTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence 2015, Submission to the Royal Commission into Family Violence, InTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, Victims of FDV related offences, Table 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related homicide, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014-2019.

- The WA Ombudsman Child Death Review considers reportable deaths of WA children and young people aged 0 to 17 years. Investigable deaths are defined in the Ombudsman’s legislation, the Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1971 (see Section 19A(3)).

- WA Ombudsman 2019, Annual Report 2018-19: Child Death Review, WA Government, p. 66.

- Brown T et al 2019, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice – Filicide Offenders, Australian Institute of Criminology.

Last updated August 2020

Although the majority of WA children and young people are living in a safe and supportive home environment, some are unable to live with their families for a range of reasons including abuse or neglect.1

The child protection system provides assistance to vulnerable children and young people who are suspected of being abused, harmed or neglected.2 In WA, the Department of Communities is responsible for child protection and investigates, responds to and manages child protection cases.

Forms of child abuse and neglect are generally categorised as physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect.3 Emotional abuse includes witnessing incidents of family and domestic violence when it is determined by the Department of Communities that the child or young person is at risk of significant harm.4 For information on family and domestic violence refer to the measure: Experiencing family and domestic violence.

This measure reports on data on WA children and young people involved in the child protection system. Most of the available data provides information about the number of children and young people involved in child protection and the provision of child protection services.

There is very limited data on the health and wellbeing outcomes of young people who have contact with the WA child protection system despite them being a particularly vulnerable group.

Abuse and neglect can have a profound impact on children and young people both in the short term and into adulthood including poor physical health, learning and developmental problems, substance abuse, mental illness, unlawful behaviour, homelessness and suicide.5

Recent research using linked data from WA has found that compared to children who have never had contact with the child protection system, children and young people who have left care are nearly twice as likely to be admitted to hospital, are three times more likely to have mental health related issues, are less likely to complete high school and more likely to have contact with the juvenile justice system.6

Child protection data only include those cases of abuse and neglect that were detected and reported.

However, child abuse and neglect often remain undetected for a variety of reasons including the private nature of the crime, the challenges children and young people experience about whether to make disclosures and whether they will be believed if they choose to disclose, and the difficulty of gathering evidence to substantiate allegations.7 The data below is therefore likely to be an underestimation of the number of children and young people being abused or neglected in WA.8

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) publishes the Child Protection Australia report on an annual basis. This report compiles data from state and territory child protection agencies.9

Children and young people receiving child protection services include those who are: subject of an investigation of a notification; on a care and protection order; or living in care.10

In 2018–19, all Australian states and territories adopted a national definition of out-of-home care which resulted in changes to the measurement in some jurisdictions. WA was already reporting data in a manner consistent with the new definition, therefore these changes have no impact on the WA data. However, data from some other jurisdictions may not match data previously published and should not be compared with data prior to 2018–19.11 Where relevant this will be noted in the tables and graphs below.

Most data on children and young people in the child protection system is not disaggregated by age groups. Therefore, the analysis in this section is generally not specific to young people aged 12 to 17 years.

Children and young people in the child protection system

At 30 June 2019, the Department of Communities reported 5,379 children and young people in care in WA.12 Of these, 1,664 were 10 to 14 years of age and 756 were 15 years and older.

|

30 June 2017 |

30 June 2018 |

30 June 2019 |

|

|

Less than 1 year |

153 |

195 |

205 |

|

1 to 4 years |

1,038 |

1,034 |

1,136 |

|

5 to 9 years |

1,552 |

1,560 |

1,618 |

|

10 to 14 years |

1,432 |

1,548 |

1,664 |

|

15 years and older* |

620 |

692 |

756 |

|

Total |

4,795 |

5,029 |

5,379 |

Source: WA Department of Communities, Annual Reports

* Includes a small number of young people who are 18 years and older and are still under the care of the WA Government.

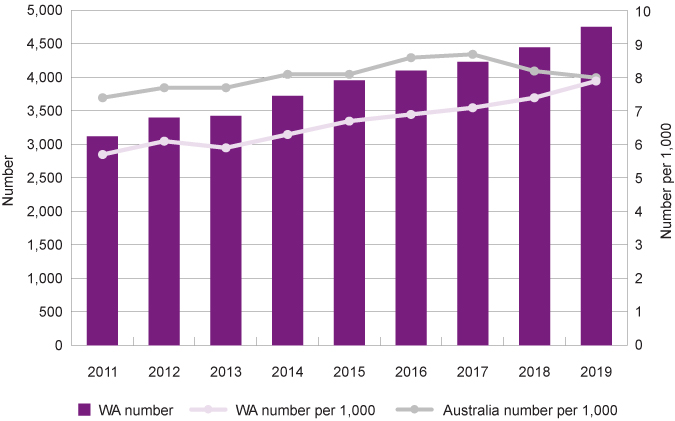

The rate of children and young people aged 0 to 17 years being in care in WA (at 30 June) has increased from 5.7 per 1,000 children and young people in 2011 to 7.9 per 1,000 in 2019.

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

|

|

2011 |

3,120 |

5.7 |

37,648 |

7.4 |

|

2012 |

3,400 |

6.1 |

39,621 |

7.7 |

|

2013 |

3,425 |

5.9 |

40,549 |

7.7 |

|

2014 |

3,723 |

6.3 |

43,009 |

8.1 |

|

2015 |

3,954 |

6.7 |

43,399 |

8.1 |

|

2016 |

4,100 |

6.9 |

46,448 |

8.6 |

|

2017 |

4,232 |

7.1 |

47,915 |

8.7 |

|

2018 |

4,448 |

7.4 |

45,756 |

8.2 |

|

2019 |

4,754 |

7.9 |

44,906** |

8.0** |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table 5.2: Children in out-of-home care, by state or territory, 30 June 2019 (and previous year’s reports)

* The AIHW reported number of children in care differs from the Department of Communities Annual Report as the Department of Communities includes unfunded living arrangements (including unendorsed arrangements). These are not included by AIHW to ensure national consistency. Refer AIHW, Child Protection Australia 2018–19 Appendixes B to G for further discussion of policy and practice differences that impact national comparability.

** The Australian total in 2018–19 is based on the new national definition of out-of-home care that excludes children on third-party parental responsibility orders. AIHW report that under the previous state-based definitions the 2018–19 total would have been 46,972 (an increase on the previous year).13

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in care, number and rate, WA and Australia, 30 June 2011 to 30 June 2019

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S5.5: Children in out-of-home care, by age group, Indigenous status and state or territory, 30 June 2019 (and previous year’s reports)

Notes:

1. The Australian rate in 2018–19 is based on the new national definition of out-of-home care that excludes children on third-party parental responsibility orders.14

2. The reduction in the number and rate of children in care across Australia in 2017–18 was principally due to a change in reporting practices in Victoria.15

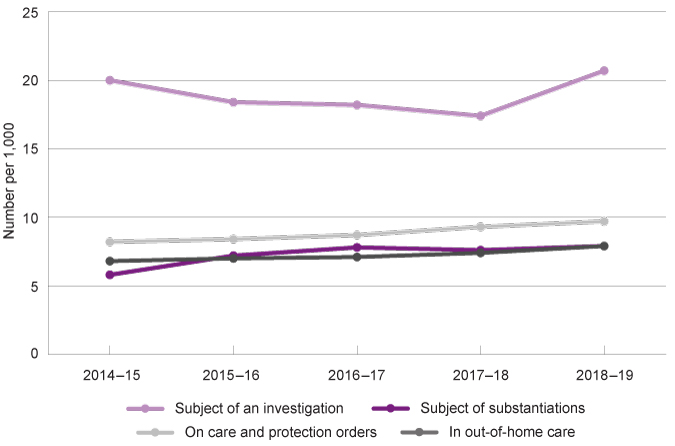

The rate of WA children and young people being subject to substantiations,16 on care and protection orders17 and in care has steadily increased in WA over the last five years, while the rate of investigations18 was decreasing until 2018–19 when it increased substantially (from 17.4 per 1,000 to 20.7 per 1,000 children and young people). In 2018–19, there was an overall increase in the rate of children and young people receiving all types of child protection services.

|

Subject |

Subject of substantiations |

On care and |

In care* |

Total receiving |

|

|

2014–15 |

20.0 |

5.7 |

8.1 |

6.7 |

27.0 |

|

2015–16 |

18.4 |

7.1 |

8.3 |

6.9 |

25.8 |

|

2016–17 |

18.2 |

7.8 |

8.7 |

7.1 |

25.9 |

|

2017–18 |

17.4 |

7.6 |

9.3 |

7.4 |

25.1 |

|

2018–19 |

20.7 |

7.9 |

9.7 |

7.9 |

29.2 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table A1: Children in the child protection system, by state or territory, 2014–15 to 2018–19 and Table 2.2 Children receiving child protection services, by state or territory, 2018–19 (and previous years equivalents)

* Children on care and protection orders and in care were measured as at 30 June each year. The remainder are during the year.

Notes:

1. Children might be involved in more than one component of the child protection system. As such, the components do not sum to the total children receiving child protection service.

2. WA out-of-home care data exclude children on third-party parental responsibility orders and from 2015–16 includes children placed in boarding schools.

3. Total receiving child protection services includes children who are subject of a notification under investigation.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in the child protection system, number per 1,000, WA, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table A1: Children in the child protection system, by state or territory, 2014–15 to 2018–19 and Table 2.2 Children receiving child protection services, by state or territory, 2018–19 (and previous years equivalents)

The significant increase in 2018–19 in the number of children and young people subject to investigations per 1,000 children and young people is related to an increase in the number of notifications received from 18,168 in 2017–18 to 20,700 and a corresponding increase in the number of investigations of notifications from 12,154 in 2017–18 to 14,200 in 2018–19.19

Aboriginal children and young people

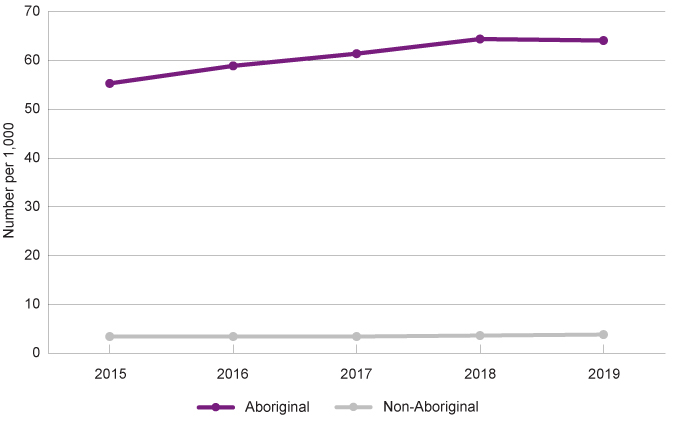

WA Aboriginal children and young people are significantly overrepresented in the child protection system in comparison to non-Aboriginal children and young people.

At 30 June 2019, the rate of WA Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care was 64.1 per 1,000 children, 17 times the rate for WA non-Aboriginal children and young people (3.8 per 1,000).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

|

|

2015 |

2,062 |

55.3 |

1,890 |

3.4 |

3,954 |

6.7 |

|

2016 |

2,212 |

58.9 |

1,887 |

3.4 |

4,100 |

6.9 |

|

2017 |

2,321 |

61.4 |

1,911 |

3.4 |

4,232 |

7.1 |

|

2018 |

2,452 |

64.4 |

1,994 |

3.6 |

4,448 |

7.4 |

|

2019 |

2,604 |

64.1 |

2,148 |

3.8 |

4,754 |

7.9 |

Source: AIHW, Child protection Australia: 2018–19, Table S5.10: Children in out-of-home care, by Indigenous status and state or territory, 30 June 2019, AIHW and previous years' tables

The rate of Aboriginal children and young people being in care across WA increased substantially from 2011 to 2018, but decreased marginally in 2019.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in care by Aboriginal status, number per 1,000, WA, 30 June 2015 to 2019

Source: AIHW, Child protection Australia: 2018–19, Table S5.10: Children in out-of-home care, by Indigenous status and state or territory, 30 June 2019, AIHW and previous years' tables

The overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in the child protection system is influenced by persistent social disadvantage which began with the process of colonisation including policies of wage-theft, assimilation and forced child removals and has continued with ongoing discrimination, poverty and inter-generational trauma.20,21

There is also recognition that child protection systems around Australia may themselves contribute to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people for various reasons. These include that when children are removed from their remote communities it is difficult to move toward family re-unification, western cultural bias regarding appropriate family practices, primary caregivers who are not biological parents being excluded from child protection proceedings, services provided not being culturally safe and child protection workers without the cultural knowledge to effectively support Aboriginal families.22,23,24,25

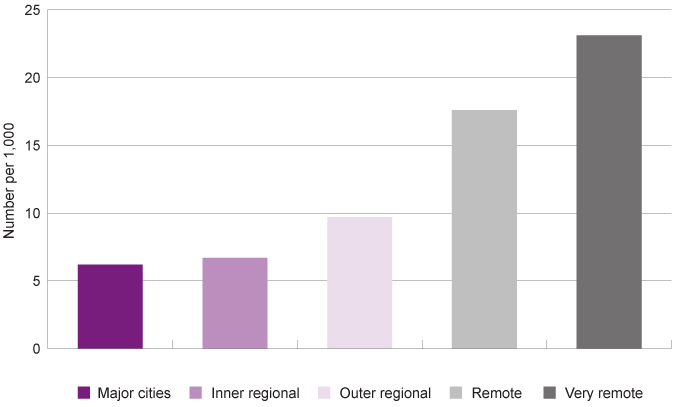

Children and young people living in remote and very remote locations in WA are three to four times more likely to be involved in the child protection system than those living in metropolitan areas. In WA, Aboriginal children and young people are more likely to live in remote and regional areas.

|

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

Australia |

|

|

Major cities |

11.8 |

3.8 |

6.2 |

3.5 |

N/A |

2.6 |

N/A |

7.4 |

|

Inner regional |

18.3 |

5.6 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

4.4 |

16.0 |

- |

10.6 |

|

Outer regional |

21.2 |

8.0 |

9.7 |

8.1 |

5.7 |

N/A |

10.0 |

10.1 |

|

Remote |

15.3 |

11.7 |

17.6 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

N/A |

30.9 |

16.2 |

|

Very remote |

N/A |

10.0 |

23.1 |

27.7 |

6.3 |

N/A |

26.8 |

20.1 |

|

Total |

13.4 |

4.9 |

7.4 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

2.6 |

18.3 |

8.6 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.7b: Children who were the subject of substantiations, by remoteness area and state or territory, 2018–19

N/A – the remoteness area classification is not valid for this jurisdiction.

Note: New South Wales did not provide data in 2018–19.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subject of substantiations by remoteness area, number per 1,000, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.7b: Children who were the subject of substantiations, by remoteness area and state or territory, 2018–19

The WA Department of Communities Child Protection Activity Performance Information report provides further information on the children and young people in care in WA.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

District |

Number |

Per cent in district |

Number |

Per cent in district |

Number |

Per cent of total |

|

Metropolitan area |

||||||

|

Perth |

131 |

45.5 |

157 |

54.5 |

288 |

5.4 |

|

Armadale |

316 |

54.3 |

266 |

45.7 |

582 |

10.8 |

|

Cannington |

249 |

56.1 |

195 |

43.9 |

444 |

8.3 |

|

Fremantle |

180 |

53.3 |

158 |

46.7 |

338 |

6.3 |

|

Joondalup |

121 |

34.2 |

233 |

65.8 |

354 |

6.6 |

|

Midland |

239 |

49.7 |

242 |

50.3 |

481 |

8.9 |

|

Rockingham |

108 |

29.8 |

255 |

70.2 |

363 |

6.7 |

|

Mirrabooka |

171 |

48.9 |

179 |

51.1 |

350 |

6.5 |

|

Fostering/Adoption |

0 |

0.0 |

11 |

100.0 |

11 |

0.2 |

|

Regional and remote |

||||||

|

Goldfields |

121 |

79.1 |

32 |

20.9 |

153 |

2.8 |

|

Great Southern |

107 |

54.6 |

89 |

45.4 |

196 |

3.6 |

|

Mid West |

210 |

85.0 |

37 |

15.0 |

247 |

4.6 |

|

Peel |

94 |

29.0 |

230 |

71.0 |

324 |

6.0 |

|

Pilbara |

199 |

93.4 |

14 |

6.6 |

213 |

4.0 |

|

South West |

152 |

40.0 |

228 |

60.0 |

380 |

7.1 |

|

West Kimberley |

206 |

99.0 |

2 |

1.0 |

208 |

3.9 |

|

East Kimberley |

159 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

159 |

3.0 |

|

Wheatbelt |

179 |

62.2 |

109 |

37.8 |

288 |

5.4 |

|

Total |

2,942 |

54.7 |

2,437 |

45.3 |

5,379* |

100.0 |

Source: Department of Communities, Activity Performance Information: 2018–19, Children and young people in care at 30 June 2019, by district

* The Department of Communities number of children in care at 30 June differs from the AIHW Child Protection report as it includes unfunded living arrangements (including unendorsed arrangements). These are not included by AIHW to ensure national consistency.

Note: The district is generally where the family of the child resides at the time of the notification, however, if a child is in care for a long period of time the district could be changed to where the child now resides.

In the Perth metropolitan area, a high proportion of children and young people in care were from Armadale (10.8% or 582), Midland (8.9% or 481) and Cannington (8.3% or 444). In certain regional and remote districts, the number of Aboriginal children and young people in care compared to non-Aboriginal children was very high, in particular East Kimberley (100.0%), West Kimberley (99.0%), Pilbara (93.4%), Mid West (85.0%) and the Goldfields (79.1%).

It should be noted that this data does not take into account the number of children and young people living in each district.

This data highlights particular districts in WA where families and communities may require more accessible, relevant and culturally appropriate services and resources to assist them to provide a safe home for their children.

The high number of substantiated child abuse and neglect cases in regional and remote areas of WA is consistent with the greater prevalence of socioeconomic disadvantage in these regions, including homelessness and overcrowding, higher unemployment, and less access to services. In research into social exclusion in Australia, the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) determined that 36.0 per cent of Australian children in remote and very remote areas were facing the highest risk of social exclusion.26

For more information on social exclusion refer to the Material basics indicator.

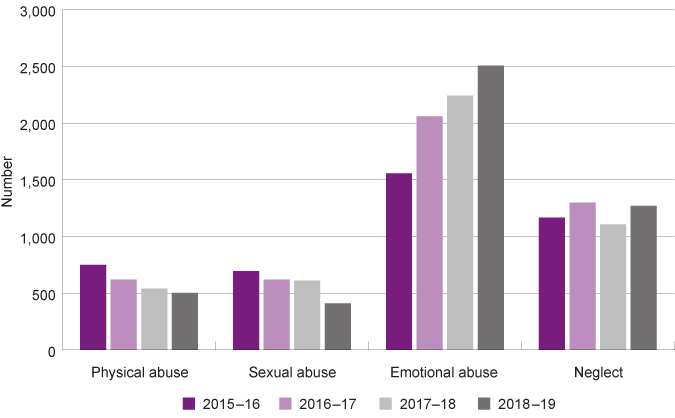

Type of abuse

In 2018–19, emotional abuse was the most common primary type27 of abuse or neglect substantiated for WA children and young people (53.2%), followed by neglect (26.9%), physical abuse (10.7%), and sexual abuse (8.7%).28

In 2015–16 the definition of emotional abuse in WA was broadened to include children witnessing family and domestic violence. Since that time the number of children subject to substantiations related to emotional abuse have increased considerably (from 1,558 in 2015–16 to 2,508 in 2018–19).

Over the same period, the number of children with substantiations where the primary type of abuse was physical or sexual abuse has decreased. Substantiations of neglect have remained relatively stable. Overall, although there have been shifts between categories, there has been a general increase in the number of children being subject to substantiations of abuse or neglect since 2015–16.

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

||

|

Number |

Per cent |

||||

|

Physical abuse |

750 |

620 |

540 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual abuse |

696 |

620 |

611 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional abuse |

1,558 |

2,059 |

2,242 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

1,168 |

1,299 |

1,107 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

26 |

35 |

30 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

4,198 |

4,633 |

4,530 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years equivalents)

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications by type of abuse or neglect, number, WA, 2015–16 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years' equivalents)

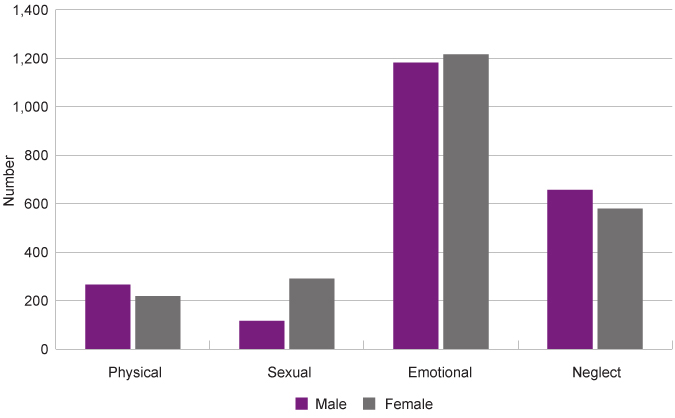

The type of abuse or neglect experienced is generally similar for male and female children and young people, with the exception that female children and young people are more likely than male children and young people to be the subjects of substantiations of sexual abuse.

|

Male |

Female |

Total* |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Physical |

266 |

11.9 |

218 |

9.4 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual |

116 |

5.2 |

290 |

12.5 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional** |

1,182 |

53.0 |

1,216 |

52.6 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

657 |

29.4 |

579 |

25.1 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

11 |

0.5 |

8 |

0.3 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

2,232 |

100.0 |

2,311 |

100.0 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.5: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19 by type of abuse or neglect, sex and state or territory

* Includes gender not stated.

** Emotional abuse includes children and young people witnessing family and domestic violence.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications by type of abuse or neglect and gender, number, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.5: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19 by type of abuse or neglect, sex and state or territory

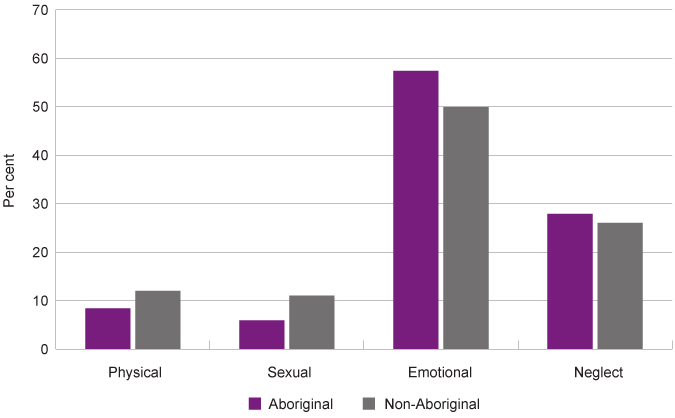

Emotional abuse (including family and domestic violence) was the most common type of substantiated abuse for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children and young people (Aboriginal: 57.4%, non-Aboriginal: 49.8%).

A lower proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal children and young people were subjects of substantiations of physical and sexual abuse (physical: 8.4% compared to 12.5%, sexual: 5.9% compared to 11.0%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Physical |

178 |

8.4 |

325 |

12.5 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual |

125 |

5.9 |

287 |

11.0 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional* |

1,211 |

57.4 |

1,297 |

49.8 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

590 |

27.9 |

681 |

26.1 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

17 |

0.3 |

16 |

0.6 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

2,111 |

100.0 |

2,606 |

100.0 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory

* Emotional abuse includes children and young people witnessing family and domestic violence.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were subjects of substantiations of notifications by Aboriginal status and type of abuse or neglect, per cent, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19,Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory

A high proportion (26.9%) of WA children and young people who have had contact with the child protection system was as a result of neglect.

Neglect is a failure to provide minimally acceptable care.29 Research has highlighted strong and consistent relationships between child abuse and neglect and economic disadvantage.30 Neglect is closely associated with families experiencing poverty and social exclusion, although not all carers in poverty are neglectful and not all children who are neglected come from financially disadvantaged families.31

Across Australia, children and young people who are living in the lowest socioeconomic areas are more likely to be subject to a child protection substantiation than children living in other more advantaged areas (34.7% were in the areas with the lowest socioeconomic status compared to 6.3% in the highest).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

1 - Lowest |

41.8 |

31.6 |

34.7 |

|

2 |

28.4 |

23.0 |

24.3 |

|

3 |

14.7 |

23.8 |

21.3 |

|

4 |

11.4 |

14.3 |

13.4 |

|

5 - Highest |

3.6 |

7.2 |

6.3 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19,Table S3.8: Children who were the subjects of substantiations, by socioeconomic area and Indigenous status, 2018–19

In 2018–19, 41.8 per cent of Aboriginal children and young people who were subject to substantiations were living in the lowest socioeconomic areas of Australia (compared to 31.6% of non-Aboriginal children and young people).

A significantly higher proportion of Aboriginal families experience social and financial disadvantage, compared to non-Aboriginal families.32

Research using data from the 2016 Census concluded that in 2016, 31.4 per cent of Aboriginal Australians were living in poverty (50.0% median income before housing costs).33

Age of children and young people in the child protection system

In 2018–19, almost 10,000 (9,988) WA children and young people aged between five and 14 years (and their families) were receiving child protection services.

Aboriginal children and young people are overrepresented in the child protection system across all age groups.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total* |

||||

|

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

|

|

Unborn |

339 |

N/A |

233 |

N/A |

671 |

N/A |

|

<1 years |

528 |

223.5 |

570 |

18.7 |

1,160 |

35.3 |

|

1 to 4 years |

1,717 |

187.0 |

2,033 |

15.6 |

3,947 |

28.4 |

|

5 to 9 years |

2,163 |

188.8 |

2,773 |

17.2 |

5,124 |

29.7 |

|

10 to 14 years |

1,981 |

177.0 |

2,750 |

18.0 |

4,864 |

29.6 |

|

15 to 17 years |

677 |

108.0 |

992 |

11.7 |

1,715 |

18.9 |

|

Total |

7,405 |

183.0 |

9,351 |

16.7 |

17,481 |

29.2 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S2.3 Children receiving child protection services, by age group, Indigenous status and state or territory, 2018–19

* Includes unknown Aboriginal status

N/A: Unborn children are covered under WA child protection legislation and are therefore included in the ‘All children’ rates. However, they are excluded in rate calculations for the ‘less than 1’ and ‘0–17’ categories. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Child Protection Report 2018-19 Child welfare series No 72, Cat no CWS 74, AIHW, p. 24.

The high rates of involvement in child protection services for infants and unborn children is discussed in the Safe in the home indicator for the 0 to 5 years age group.

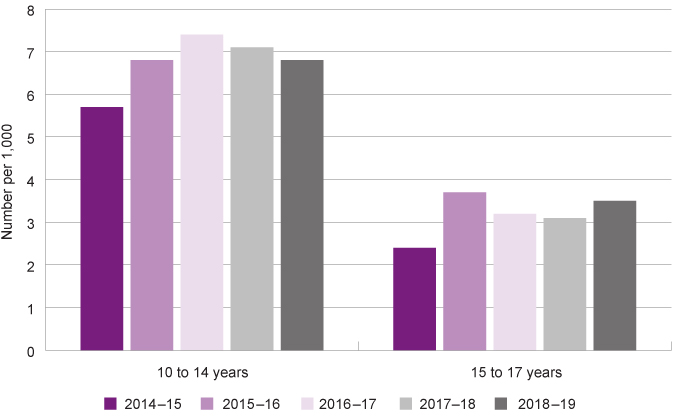

Data on substantiations by age group highlights that infants and younger children are more likely to be subject to substantiations than young people over 15 years of age, with 15 to 17 year-old young people in WA significantly less likely to be subjects of substantiations with a rate of 3.2 per 1,000 in 2017–18.

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

<1 years |

7.6 |

9.8 |

12.0 |

11.8 |

13.0 |

|

1–4 years |

5.6 |

7.2 |

8.4 |

8.1 |

8.8 |

|

5–9 years |

6.6 |

7.5 |

8.2 |

7.7 |

8.0 |

|

10–14 years |

5.7 |

6.8 |

7.4 |

7.1 |

6.8 |

|

15–17 years |

2.4 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.5 |

|

0–17 years |

5.5 |

6.8 |

7.5 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

|

Total |

5.7 |

7.1 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.9 |

|

Children and young people |

3,382 |

4,198 |

4,633 |

4,530 |

4,717 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table 3.3: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications, by age group and state or territory, 2018–19 (rate) (and previous years’ reports)

Note: Unborn children are covered under WA child protection legislation and are therefore included in the ‘All children’ rates. However, they are excluded in rate calculations for the ‘less than 1’ and ‘0–17’ categories.

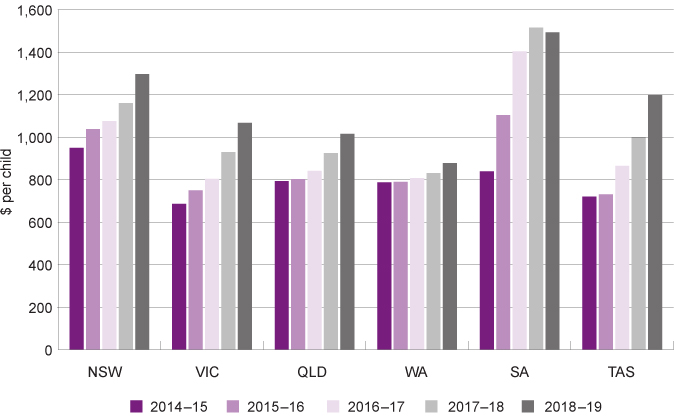

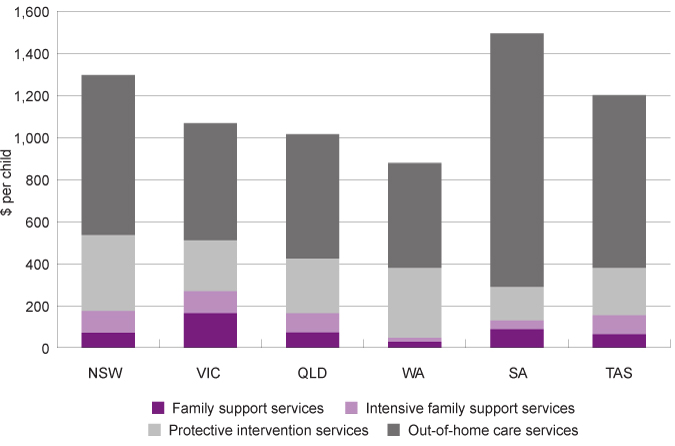

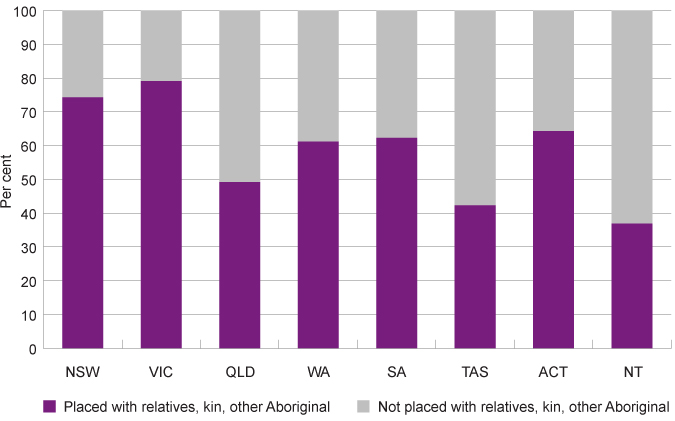

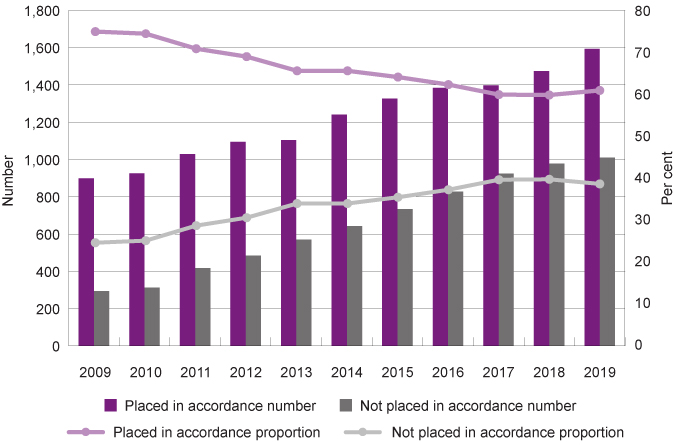

The higher rates of substantiation for infants is discussed in the Safe in the home indicator for the 0 to 5 years age group.