Risk-taking and healthy behaviours

Most young people in WA engage in healthy behaviours, yet participating in risk-taking behaviour including experimentation with substances and sexual activity can be part of the transition to adulthood. Evidence suggests that the earlier young people commence consuming alcohol and other drugs, the greater the likelihood of dependency and associated problems in later life.1 Good sexual health is also important for young people’s physical health and overall wellbeing and it is critical that young people are well informed and supported to make healthy choices.2

It is imperative to address any health concerns or risky behaviours early to improve future health and wellbeing outcomes and quality of life for young people.3

Last updated August 2021

Some data is available on WA young people aged 12 to 17 years engaging in unhealthy and risk-taking behaviours.

Overview

This indicator considers some key measures of unhealthy and risk-taking behaviours of young people, which include the consumption of alcohol and other drugs, and engagement in unsafe sexual activities.

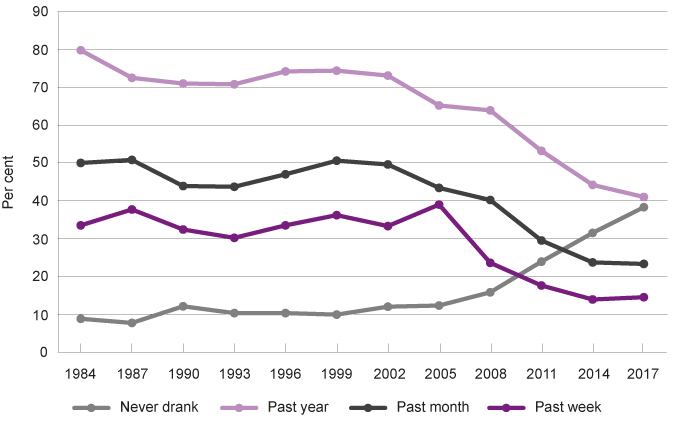

The rates of alcohol use in young people aged 12 to 17 years have declined steadily over the past thirty years in WA. Furthermore, the number of young people in WA who have never consumed alcohol has increased from just under one in ten (9%) in 1984 to three in five (38.3%) young people in 2017.

Prevalence and recency of alcohol use for students aged 12 to 17 years, per cent, WA, 1984 to 2017

Source: Mental Health Commission National Drug Strategy, 2017 ASSAD Alcohol Bulletin, WA Government

Research indicates that there has been a significant decrease in both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people smoking tobacco in the last decade.

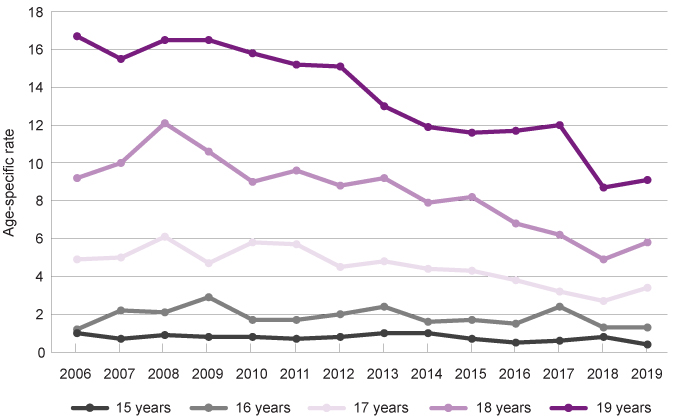

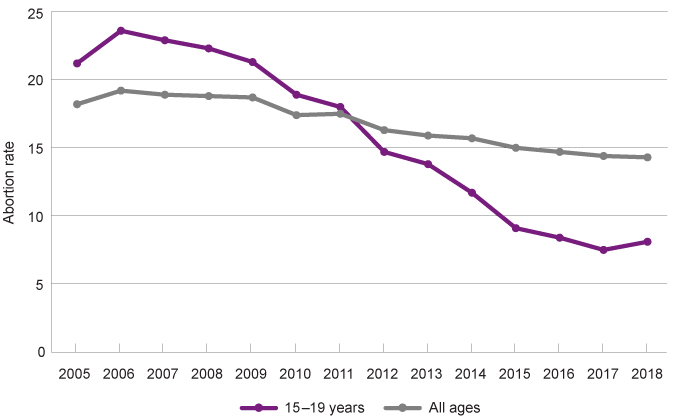

Birth rates for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young mothers aged 15 to 19 years in WA have been decreasing over the last 20 years.

Areas of concern

More than one-half (58.1%) of young people in Years 10 to 12 report having drunk more than a few sips of alcohol compared to 20.7 per cent in Years 7 to 9.

While overall trends highlight that illicit drug use is declining, almost one in five (18.1%) young people in WA reported having ever used an illicit drug in 2017.

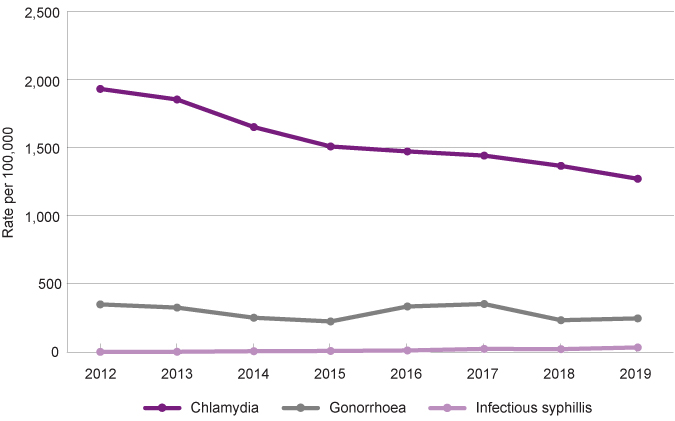

A majority (61.6%) of sexually active Australian young people do not always use a condom during sex and are at risk of contracting a sexually transmissible infection.

Last updated August 2021

Research indicates alcohol can adversely affect brain development in adolescents and be linked to health complications and alcohol-related complications later in life.1 Chronic health conditions linked to alcohol include heart problems, cancer and liver damage.2 Alcohol is also a contributing factor to the three leading causes of death among adolescents – unintentional injuries, homicide and suicide.3

Young people’s alcohol use is also associated with increased risk-taking behaviour including risky sexual behaviour, sexual coercion, drug use, anti-social behaviour, violence and self-harm.

It is therefore critical to focus on reducing risk factors that contribute to young people drinking, to improve the health and wellbeing outcomes for WA young people.

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)’s guidelines specify that the safest option for children and young people under the age of 18 years is to consume no alcohol at all. It specifically states that young people under 15 years are at greatest risk of poor health outcomes from drinking alcohol.4

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on healthy behaviours.5

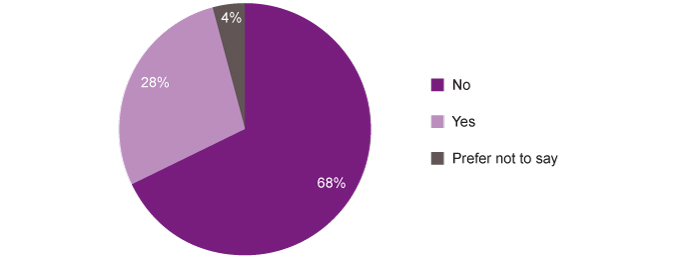

This survey showed that more than one-half (57.8%) of young people in Year 7 to Year 12 reported that they have never drunk more than a few sips of alcohol.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

59.4 |

56.5 |

60.0 |

47.4 |

54.0 |

57.8 |

|

Yes |

36.5 |

39.8 |

36.3 |

49.0 |

40.6 |

38.3 |

|

Prefer not to say |

4.1 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

5.4 |

3.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences between male and female students or students in different geographical locations, although a higher proportion of young people in regional locations than metropolitan or remote, reported having ever drunk alcohol (49.0% compared to 36.3% and 40.6%).

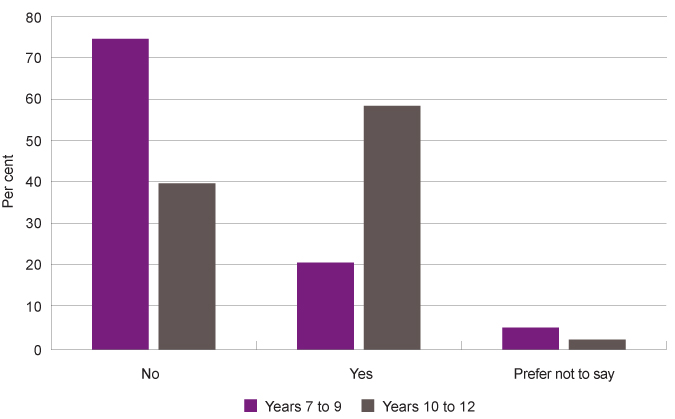

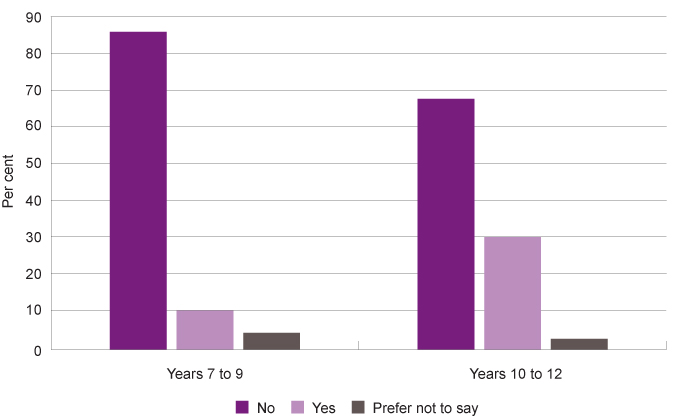

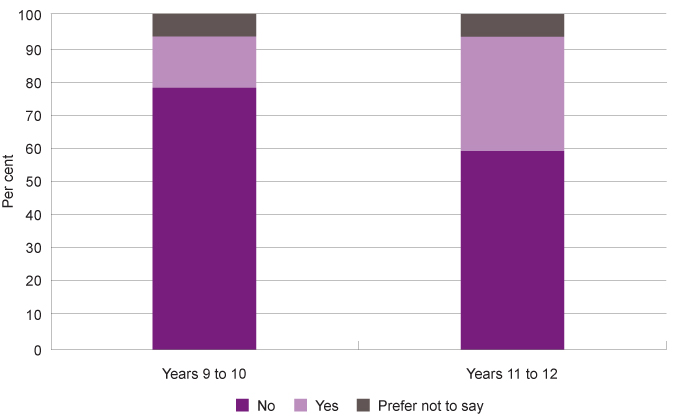

There were significant differences between year groups, with 58.1 per cent of young people in Years 10 to 12 having drunk alcohol compared to 20.7 per cent in Years 7 to 9.

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

No |

74.1 |

39.6 |

|

Yes |

20.7 |

58.1 |

|

Prefer not to say |

5.2 |

2.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who reported whether they have ever drunk alcohol (more than just a few sips, like a full can of beer or a glass of wine) by year group, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

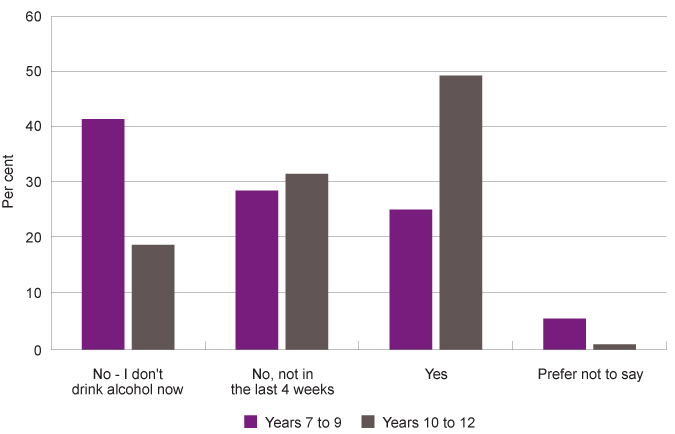

Among those students who had drunk alcohol, 49.0 per cent of Year 10 to 12 and 25.0 per cent of Year 7 to 9 students reported having drunk alcohol in the last four weeks.

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

No - I don't drink alcohol now |

41.2 |

18.7 |

|

No, not in the last 4 weeks |

28.4 |

31.4 |

|

Yes |

25.0 |

49.0 |

|

Prefer not to say |

5.5 |

0.9 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who have ever drunk alcohol responding to the question ‘In the last 4 weeks, did you drink alcohol?’, by response category and year group

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

That is, around 28.2 per cent of all Year 10 to 12 students and 5.1 per cent of all Year 7 to Year 9 students reported having drunk alcohol in the last four weeks.

Of the Year 10 to Year 12 students who had drunk alcohol, more than one-in-ten (13.1%) male students had their first drink when they were under 12 years-old compared to 5.9 per cent of female students.

For the students in the survey, 81.2 per cent of students who had drunk alcohol reported they usually drink with friends, 40.2 per cent usually drink with family (which could be siblings) and 17.6 per cent reported they usually drink by themselves. Similar responses were reported by male and female students, across regions and by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people.

The Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug (ASSAD) survey is a national survey of young people’s substance use conducted in high schools around Australia every three years. It surveys approximately 20,000 Australian young people aged 12 to 17 years. The most recently published survey was conducted in 2017 with 3,361 WA young people aged from 12 to 17 years from 46 randomly selected government, Catholic and independent schools across the State.

The results for the ASSAD survey differ from the Speaking Out Survey due to different survey methodologies and time periods. In particular, the ASSAD survey defines never drinking as ‘did not even have a sip of an alcoholic drink in their lifetime’.6 Nevertheless, the data provides an analysis of change over time.

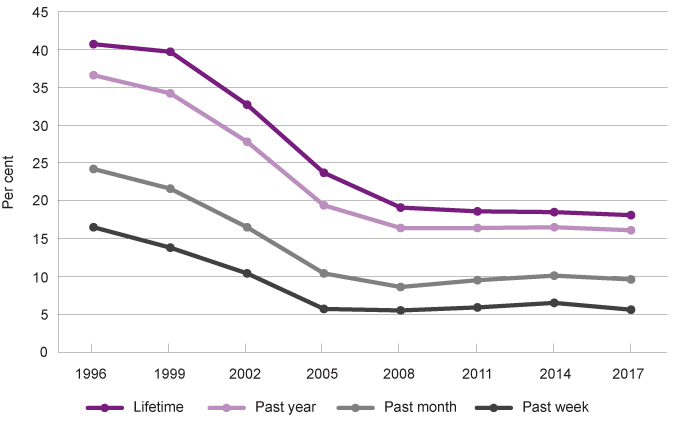

According to the ASSAD results, the rates of alcohol use by young people aged 12 to 17 years have declined steadily over the past thirty years in WA.

|

Never drank* |

Past year |

Past month |

Past week |

|

|

1984 |

8.8 |

79.8 |

50.0 |

33.5 |

|

1987 |

7.7 |

72.5 |

50.8 |

37.7 |

|

1990 |

12.1 |

71.0 |

43.9 |

32.4 |

|

1993 |

10.3 |

70.8 |

43.7 |

30.2 |

|

1996 |

10.3 |

74.2 |

47.0 |

33.5 |

|

1999 |

9.9 |

74.4 |

50.6 |

36.2 |

|

2002 |

12.0 |

73.1 |

49.6 |

33.3 |

|

2005 |

12.3 |

65.2 |

43.4 |

39.0 |

|

2008 |

15.8 |

63.9 |

40.2 |

23.6 |

|

2011 |

23.9 |

53.2 |

29.5 |

17.6 |

|

2014 |

31.5 |

44.2 |

23.7 |

13.9 |

|

2017 |

37.8 |

41.8 |

24.1 |

14.7 |

Source: WA Mental Health Commission, 2017 ASSAD Alcohol Bulletin

* Never drank is defined as did not have even a sip of an alcoholic drink in their lifetime.

Prevalence and recency of alcohol use for students aged 12 to 17 years, per cent, WA, 1984 to 2017

Source: WA Mental Health Commission, 2017 ASSAD Alcohol Bulletin

WA high school students who had consumed alcohol in the past week has reduced to 14.7 per cent in 2017 in comparison to 33.5 per cent in 1984. Furthermore, the reported number of high school students in WA that have never consumed alcohol has increased from nine per cent in 1984 to 37.8 per cent in 2017.

These results may reflect strategies that have been developed to reduce alcohol consumption. These strategies include increasing the price of alcohol, limiting physical availability and educating children and young people and their parents and carers on the health and social consequences of alcohol consumption.7,8

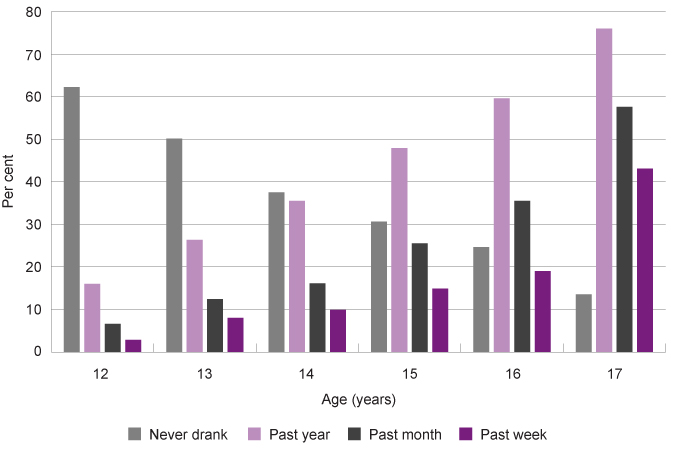

The proportion of young people consuming alcohol increases steadily as they age.

|

12 years |

13 years |

14 years |

15 years |

16 years |

17 years |

|

|

Never drank* |

62.2 |

50.1 |

37.5 |

30.6 |

24.6 |

12.6 |

|

Past year |

16.0 |

26.3 |

35.5 |

47.9 |

59.6 |

77.4 |

|

Past month |

6.6 |

12.4 |

16.1 |

25.5 |

35.5 |

59.8 |

|

Past week |

2.8 |

8.0 |

9.9 |

14.9 |

19.0 |

41.2 |

Source: WA Mental Health Commission, 2017 ASSAD Alcohol Bulletin

* Never drank is defined as did not have even a sip of an alcoholic drink in their lifetime.

Prevalence and recency of alcohol use for students by age, per cent, WA, 2017

Source: WA Mental Health Commission, 2017 ASSAD Alcohol Bulletin

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) is a triennial survey that collects information on alcohol and drug use patterns, attitudes and behaviours from approximately 24,000 people across Australia.9 The NDSHS asked participants who were 14 to 24 years-old, what age they were when they first drank a standard drink of alcohol. Based on their responses, the average age of first drinking alcohol across Australia was 16.2 years in 2019, up from 16.1 in 2016 and 15.7 in 2013.10

Risky drinking

The NHMRC guidelines do not have risky drinking guidelines for young people, as all alcohol consumption is considered detrimental to their health and wellbeing. However, single occasion risky drinking is believed to be the most common form of risky drinking as most young people do not drink regularly. For adults, risky drinking on a single occasion is defined as five or more standard drinks.11 In general, surveys of young people report against the adult single occasion risky drinking guidelines.

While there has been a welcome increase in the proportion of young people not drinking, the incidence of risky drinking has not changed significantly in the past 20 years. In 1984, 16.1 per cent of WA young people drank at risky levels on a single occasion in the past week, this increased to 27.0 per cent in 1996 and 30.0 per cent in 2017.12

The NDSHS data shows a reduction in single occasion risky drinking from 2010 to 2019 across Australia for young people aged 14 to 17 years (20.5% of young people in 2010 to 8.9% of young people in 2019).13 The data reported by jurisdiction has a very high relative standard error and has not been reproduced here.

The high sampling error across almost all jurisdictions in recent years is of concern, this suggests that the sample sizes were not sufficient to provide valid and reliable estimates for this critical age group by jurisdiction.

The SOS19 data found that of the young people who had drunk in the last four weeks (16.0% of all students), 31.0 per cent had not drunk five or more alcoholic drinks in one session, 44.4 per cent had done so on one occasion in the last four weeks and 14.2 per cent had done so on two or three occasions in the last four weeks. Eight (7.9%) per cent of students who had drunk in the last four weeks reported having had more than four standard drinks on a single occasion on a weekly basis.

While the numbers are small, this equates to about 1.0 per cent of all Year 7 to Year 12 students drinking at risky levels on a weekly basis.

|

Male |

Female |

All |

|

|

None |

34.6 |

28.5 |

31.0 |

|

Once in the past 4 weeks |

42.5 |

46.4 |

44.4 |

|

Two or three times in the past 4 weeks |

12.0 |

15.9 |

14.2 |

|

Every week |

7.7 |

4.0 |

5.5 |

|

Several times a week |

1.9 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

|

Prefer not to say |

N/A |

3.4 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Similar proportions of male and female Year 7 to Year 12 students who had drunk alcohol in the last four weeks, had engaged in risky drinking practices.

The NHMRC guidelines state there is a high level of health risk associated with the consumption of any alcohol for ages 15 years and under, therefore many of these WA young people are consuming alcohol at a very risky level.

The Young Australians’ Alcohol Reporting System (YAARS) is a national research project that aimed to provide insight into the risky drinking patterns of Australian young people. In late 2016 and early 2017, a total of 965 14 to 19 year-olds were interviewed or surveyed in WA. From this group, 479 young people were identified as ‘risky drinkers’.14

For these risky drinkers the most popular beverage type was spirits, with 76 per cent of young people drinking spirits at their last risky drinking session. Female young people were more likely to drink spirits (80%) and ready to drink beverages (46%), while male young people were also more likely to drink spirits (71%) followed by beer (67%).15

Parental use of alcohol can have a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of children and young people in their care. For many young people, the family environment is their first introduction to alcohol, with attitudes and behaviours associated with drinking being modelled by carers or parents in the young person’s home. Research has highlighted a parents’ drinking behaviour is positively correlated with adolescents’ use of alcohol.16

In 2011, the Commissioner for Children and Young People consulted with approximately 300 WA young people aged 14 to 17 years about their views on alcohol. More than half of the young people reported that their parents were a significant influence on their decisions about alcohol consumption.17

In the 2017 ASSAD survey, WA young people aged 12 to 17 years who had reported drinking alcohol in the last week also recorded the sources of their alcohol supply. Results highlighted that one in three WA young people sourced their alcohol from their friends (33.6%) and 22.7 per cent sourced it from their parents. A high proportion (15.9%) of 12 to 15 year-olds reported taking alcohol from home without permission.18

Of particular concern is that 24.7 per cent of WA young people aged 12 to 15 years who reported drinking alcohol reported their parents gave it to them.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies conduct the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children and in 2016 explored parental influences on adolescent’s alcohol use. Results indicated a 10 per cent statistically significant increase in drinking levels for young people who had a mother who drank some alcohol and a 5 per cent increase in drinking levels for young people who had a father who drank some alcohol.19

In a two-parent household the prevalence of a young person having consumed alcohol in the last 12 months was approximately 9 per cent where neither parents drank at a risky level,20 16 per cent where the father drank at a risky level and 23 per cent where both parents reported regularly consuming alcohol.21

Aboriginal young people

Both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people in Australia consume alcohol. There are however, significant social factors that increase the risk of alcohol consumption and risky drinking among Aboriginal communities. These intersecting factors include economic marginalisation, discrimination, cultural dispossession, family conflict or violence and family history of alcohol misuse.22

The NDSHS reports a decline in single occasion risky alcohol consumption at least monthly for Aboriginal young people and adults (people aged 14 years and over, including adults) from 2010 (39.4%) to 2019 (35.4%). Furthermore, there was an increase in the proportion of Aboriginal people aged 14 years and over who were drinking at single occasion low risk levels (20.9% in 2010 compared to 27.8% in 2019).23

In 2018–19, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) conducted the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey which included a nationally representative sample of around 13,000 Aboriginal people in remote and non-remote locations. This survey compared alcohol consumption for young people aged 15 to 17 years to the NHMRC guidelines for single occasion risky drinking.

|

2012-13 |

2018-19 |

|

|

Did not exceed NHMRC guidelines |

17.3 |

10.9 |

|

Exceeded NHMRC guidelines |

23.7 |

17.6 |

|

Consumed alcohol 12 or more months ago |

5.7 |

3.4 |

|

Never consumed alcohol |

52.0 |

68.0 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Table 14 Alcohol Consumption – Short term or single occasion risk by age, Indigenous status and sex, 2012-13 – Australia and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Table 14.3 Alcohol consumption—Single occasion risk by age, sex and Indigenous status, persons aged 15 years and over, 2017–18 and 2018–19

This survey found that there has been a substantial increase in the proportion of Aboriginal young people aged 15 to 17 years who have never consumed alcohol (from 52.0% in 2012–13 to 68.0% in 2018–19).

There is no data available from this survey on alcohol consumption for Aboriginal children and young people in WA.

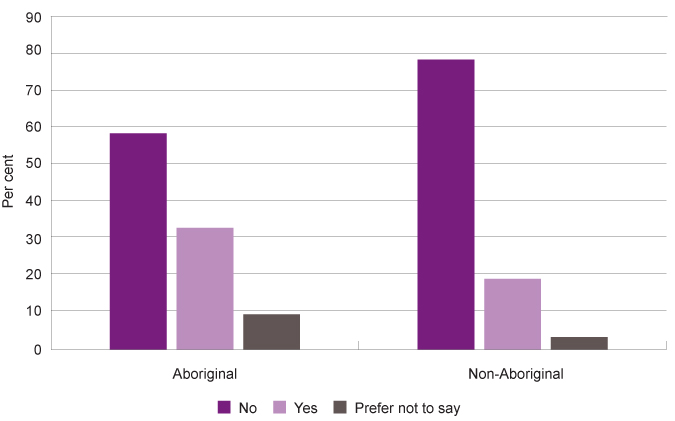

In the SOS19 data, a greater proportion of non-Aboriginal than Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they have never drunk more than a few sips of alcohol (58.4% compared to 49.9%), although this difference was not statistically significant. A significantly greater proportion of Aboriginal students than non-Aboriginal students reported that they would prefer not to say whether they had drunk alcohol (9.3% compared to 3.5%).

|

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

|

|

No |

58.4 |

49.9 |

|

Yes |

38.1 |

40.7 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.5 |

9.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Education about alcohol

In SOS19, young people in Years 7 to 12 were asked how much they have learnt about alcohol at school.

Most (77.1%) young people reported that they had learnt a lot (41.1%) or some (36.0%) about alcohol at school. While, 16.3 per cent reported they had only learnt a little bit and 6.7 per cent reported they had learnt nothing.

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

All |

|

|

Nothing |

9.4 |

3.6 |

6.7 |

|

A little bit |

16.7 |

15.8 |

16.3 |

|

Some |

37.2 |

34.6 |

36.0 |

|

A lot |

36.7 |

46.0 |

41.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Of concern is that almost one in five (19.4%) students in Years 10 to 12 reported that they had learnt either nothing (3.6%) or a little bit (15.8%) about alcohol in school.

Most (87.9%) high school students reported that they feel like they know enough about the health impacts of alcohol, while 7.1 per cent did not feel like they knew enough and 5.0 per cent were not sure. These proportions were similar for students in Years 7 to 9 and Years 10 to 12.24

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex children

For information on LGBTI young people’s consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Culturally and linguistically diverse young people

For information on culturally and linguistically diverse young people’s consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Young people in the youth justice system

For information on the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs of young people in youth detention refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Endnotes

-

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2009, Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol, NHMRC, p. 61.

-

Ibid, p. 120.

-

Australian Drug Foundation (ADF) 2019, Alcohol and young people, ADF.

-

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2009, Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol, NHMRC, p. 4.

-

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

-

Guerin N and White V 2018, Statistics and Trends: Australian Secondary School Students’ Use of Tobacco, Alcohol, Over-the-counter Drugs, and Illicit Substances, Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer Council of Victoria

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2017, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Drug Statistics series no 32 Cat no PHE 214, AIHW, p. 26.

-

Department of Health 2017, National Drug Strategy 2017-2026, Australian Government.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2017, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings, AIHW, p. 3 and 134.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, Table S3.31:Age of initiation, recent drinkers and ex–drinkers aged 14–24, 2001 to 2019 (years), AIHW. This is the average (mean) age that 14–24 year olds first consumed a full serve of alcohol.

-

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2009, Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol, NHMRC.

-

Mental Health Commission (MHC) 2019, Alcohol trends in Western Australia 2017: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, MHC.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table S.22: People at risk of injury on a single occasion of drinking(a), by age and state/territory, 2007 to 2019 (per cent), AIHW.

-

Pandzic I et al 2017, Young Australians Alcohol Reporting System (YAARS) Report 2016/17 – Western Australian main findings, National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, p. 7.

-

Ibid, p. 13.

-

Homel J and Warren D 2016, Parental influences on adolescent alcohol use, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

-

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2011, Speaking out about: Alcohol-related harm on children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

-

Mental Health Commission (MHC) 2019, Alcohol trends in Western Australia 2017: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, MHC.

-

Homel J and Warren D 2016, Parental influences on adolescent alcohol use, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 72-73.

-

Risky drinking was categorised as five or more drinks on a single occasion, at least twice a month.

-

Homel J and Warren D 2016, Parental influences on adolescent alcohol use, in The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 73.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2011, Substance use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, AIHW, p. 11.

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, , Table 8.2: Use of drugs by Indigenous status, people aged 14 and over, 2010 to 2019 (age standardised col per cent), AIHW.

-

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

Last updated August 2021

Smoking greatly increases the risk of many cancers, cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and many other serious medical conditions.1 Research has shown that the younger a person starts smoking, the less likely they are to stop.2

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on healthy behaviours.3

Overall, more than three-quarters (76.7%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students have never smoked a cigarette, even a few puffs, while 19.6 per cent have tried cigarette smoking.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

79.2 |

75.1 |

79.1 |

67.7 |

65.2 |

76.7 |

|

Yes |

17.2 |

21.3 |

17.6 |

27.3 |

30.5 |

19.6 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.6 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

4.9 |

4.3 |

3.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Of those that have tried cigarette smoking, 59.2 per cent have smoked a whole cigarette. That is, of all high school students, 11.6 per cent have smoked a whole cigarette.

Students in regional and remote locations are more likely to have tried cigarette smoking than those in the metropolitan area (27.3% and 30.5% compared to 17.6%).

Students in Year 10 to 12 are more likely to have tried cigarette smoking than those in Years 7 to 9 (30.1% compared to 10.4%).

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

No |

85.2 |

67.2 |

|

Yes |

10.4 |

30.1 |

|

Prefer not to say |

4.4 |

2.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who reported whether they have ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs by year group, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Most (57.3%) Year 7 to Year 12 students who reported they had tried smoking a cigarette did not smoke now, however one in 10 reported that they now smoke on most days (3.5%) or daily (7.3%).4 This equates to 2.1 per cent of all Year 7 to Year 12 students.

There were no significant differences in cigarette smoking between male and female students in WA.

|

Male |

Female |

All |

|

|

Never, I don't smoke now |

59.7 |

56.8 |

57.3 |

|

Occasionally |

16.0 |

20.0 |

18.2 |

|

Once or twice a month |

5.9 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

|

Once or twice a week |

3.6 |

6.6 |

5.2 |

|

Most days |

4.6 |

1.9 |

3.5 |

|

Daily |

5.7 |

7.9 |

7.3 |

|

Prefer not to say |

4.5 |

1.9 |

3.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) is a triennial survey that in 2019 collected information from approximately 23,000 people across Australia. In this survey participants were asked about their drug use patterns, attitudes and behaviours.

The NDSHS reports on the proportion of people who have ‘never smoked’, however this is actually people who have never smoked more than 100 cigarettes. There is no measure of young people who have never smoked even one puff in the NDSHS.

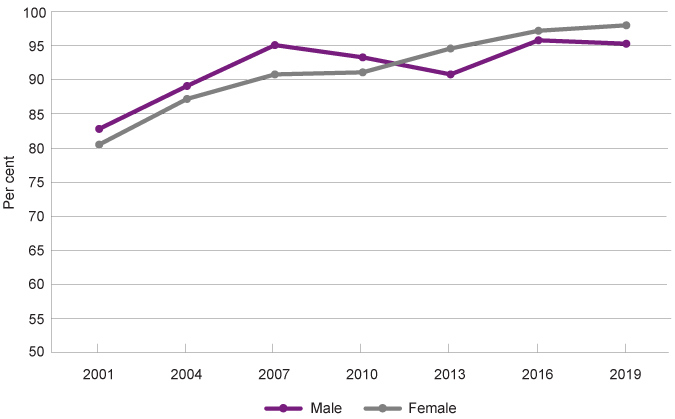

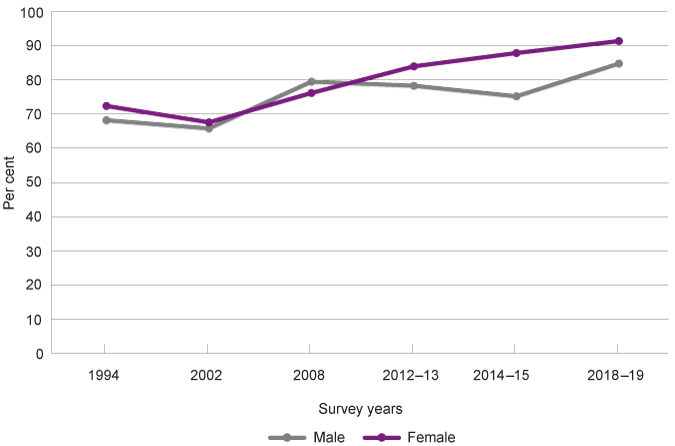

Across Australia, there has been a steady increase in the proportion of young people aged 14 to 17 years who have never smoked more than 100 cigarettes (81.7% in 2001 compared to 96.6% in 2019).

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

2001 |

82.8 |

80.5 |

81.7 |

|

2004 |

89.1 |

87.2 |

88.1 |

|

2007 |

95.1 |

90.8 |

93.0 |

|

2010 |

93.3 |

91.1 |

92.2 |

|

2013 |

90.8 |

94.6 |

92.6 |

|

2016 |

95.8 |

97.2 |

96.4 |

|

2019 |

95.3 |

98.0 |

96.6 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 2.7: Tobacco smoking status, by age and sex, 2001 to 2019

In 2019, female young people across Australia were slightly more likely to have never smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime than male young people (98.0% compared to 95.3%).

Proportion of young people aged 14 to 17 years who have never smoked (more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime) by gender, per cent, Australia, 2001 to 2019

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 2.7: Tobacco smoking status, by age and sex, 2001 to 2019

The NDSHS also shows a reduction in Australian young people aged 14 to 19 years smoking on a daily basis from 2010 to 2019 (6.9% of young people in 2010 to 3.7% of young people in 2019).5 Similarly, there has been a concurrent reduction in Australian young people aged 14 to 17 years smoking on a daily basis (subject to the margin of error).

|

14 to 17 years |

14 to 19 years |

|

|

2007 |

4.6 |

7.3 |

|

2010 |

3.7 |

6.9 |

|

2013 |

5.1 |

7.0 |

|

2016 |

2.2* |

3.0 |

|

2019 |

1.9* |

3.7 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table S.9: Daily tobacco smoking status, by age and state/territory, 2007 to 2019

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

The data reported by jurisdiction has a very high relative standard error and has not been reproduced here.

The high sampling error across almost all jurisdictions in recent years is of concern, this suggests that the sample sizes were not sufficient to provide valid and reliable estimates for this critical age group by jurisdiction.

The Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug (ASSAD) survey is a national survey of young people’s alcohol and drug use conducted in high schools around Australia every three years. It surveys approximately 20,000 young people aged 12 to 17 years.

According to results from the 2017 ASSAD survey, 83.0 per cent of Australian secondary students aged 12 to 17 years had never smoked (never even had a puff of a cigarette).

|

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

12-17 |

|

|

Never smoked |

95.0 |

93.0 |

88.0 |

78.0 |

72.0 |

65.0 |

83.0 |

|

More than 100 cigarettes in lifetime |

<1.0 |

<1.0 |

1.0 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

2.0 |

|

Past year |

3.0 |

5.0 |

9.0 |

17.0 |

23.0 |

28.0 |

13.0 |

|

Past month |

2.0 |

2.0 |

5.0 |

9.0 |

13.0 |

16.0 |

7.0 |

|

Current (past 7 days) |

2.0 |

2.0 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

8.0 |

11.0 |

5.0 |

|

Committed smokers (3+ days in past 7 days) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

3.0 |

Source: Department of Health, Secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs in 2017, Table 3.1 Percentage of secondary students in Australia who have smoked in the past week, past month, past year, or lifetime, by age and sex

This survey also reports that five per cent of young people aged 12 to 17 years had smoked in the past week.6

Unsurprisingly the proportion of young people smoking increases as they get older. The lowest proportion of students who had smoked in the past month was 12 and 13 year-olds (2.0%), which increased with age (16.0% for 17 year-olds).

Consistent with the NDSHS survey this survey reported a significant drop in the proportion of Australian high school students smoking from 1999 to 2017. This was across all categories of smoking (ever smoking, smoking in the past year, past month, past week, as well as committed and daily smokers).7

Age of initiation

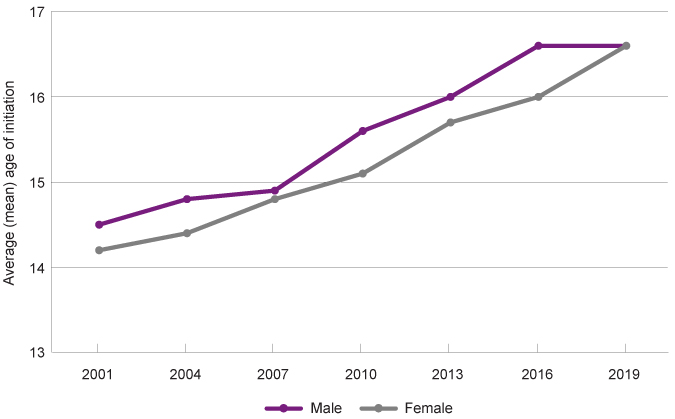

The average age at which Australian young people aged 14 to 24 years smoked their first full cigarette has steadily risen from 14.3 years in 2001 to 16.6 years in 2019.

|

Males |

Females |

Persons |

|

|

2001 |

14.5 |

14.2 |

14.3 |

|

2004 |

14.8 |

14.4 |

14.6 |

|

2007 |

14.9 |

14.8 |

14.9 |

|

2010 |

15.6 |

15.1 |

15.4 |

|

2013 |

16.0 |

15.7 |

15.9 |

|

2016 |

16.6 |

16.0 |

16.3 |

|

2019 |

16.6 |

16.6# |

16.6 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 2.11: Age of initiation(a) of tobacco use, people aged 14–24 who have ever smoked a full cigarette, by sex, 2001 to 2019 (years)

# Statistically significant change between 2016 and 2019.

Average (mean) age of initiation of tobacco use for young people aged 14 to 24 years by age in years and gender, age in years, Australia, 2001 to 2019

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 2.11: Age of initiation(a) of tobacco use, people aged 14–24 who have ever smoked a full cigarette, by sex, 2001 to 2019 (years)

In previous years, Australian male young people were generally slightly older than Australian female young people when they smoked their first cigarette. However, in 2019 the average age of initiation across Australia for male and female young people was the same.

From the same survey, the average age of initiation for WA young people aged 14 years to 24 years has also increased from 15.8 in 2007 to 16.5 in 2019, which is similar to the Australian average of 16.6 years in the same year.

|

Age of initiation |

|

|

2007 |

15.8 |

|

2010 |

15.5 |

|

2013 |

15.7 |

|

2016 |

16.6 |

|

2019 |

16.5 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table S.31: Age of initiation of lifetime drug use, people aged 14 and over, by state/territory, 2007 to 2019 (years)

In SOS19, of the 30.1 per cent of Year 10 to Year 12 WA students who reported they had smoked a cigarette (even just a puff), almost two in five (37.1%) tried their first cigarette when they were under 15 years of age.

|

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

11 and under |

8.7 |

|

12 to 14 years |

28.4 |

|

15 years and older |

52.6 |

|

I don't remember |

8.9 |

|

Prefer not to say |

1.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Note: This does not correspond to the ‘age of initiation’ which is generally calculated by including young adults (18 to 24 years) responses regarding when they first started smoking. In the above table, only older students can respond with older age groups, therefore the younger age groups have a higher likelihood of having been selected.

Aboriginal young people

The NDSHS reports that Aboriginal people aged 14 years and over (including adults) are more than twice as likely to smoke tobacco on a daily basis than non-Aboriginal people (24.9% compared to 10.7%). There has however been a steady decrease in the proportion of Aboriginal people smoking on a daily basis over the past decade (34.8% in 2010 compared to 24.9% in 2019).8

In the SOS19 data, Aboriginal students were significantly more likely to have tried cigarette smoking than non-Aboriginal students (32.6% of Aboriginal students had tried compared to 18.9% of non-Aboriginal students).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

No |

58.0 |

77.8 |

|

Yes |

32.6 |

18.9 |

|

Prefer not to say |

9.4 |

3.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who reported whether they have ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

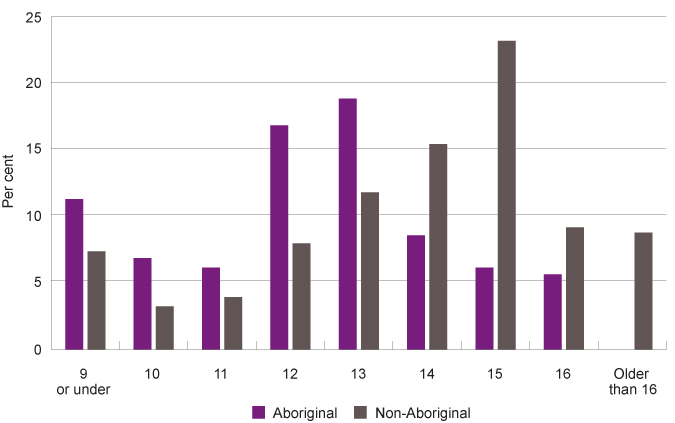

Although the differences were not statistically significant, of the students who had tried smoking, Aboriginal students were more likely than non-Aboriginal students to report smoking at an earlier age.

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who had ever tried cigarette smoking responding to the question ‘how old were you when you first smoked a cigarette?’ by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Note: This does not correspond to the ‘age of initiation’ which is generally calculated by including young adults’ (18 to 24 years) responses regarding when they first started smoking. In the above table, only older students can respond with older age groups, therefore the younger ages have a higher likelihood of having been selected.

In 2018–19, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) conducted the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey which included a nationally representative sample of around 10,500 Aboriginal people in remote and non-remote locations.9

In this survey, 9.7 per cent of Aboriginal young people aged 15 to 17 years reported smoking tobacco daily, which was a substantial reduction from the result in 2012–13 of 17.6 per cent.

|

2012-13 |

2018-19 |

|

|

Never smoked |

76.7 |

84.6 |

|

Ex-smoker |

4.3* |

3.6 |

|

Daily smoker |

17.6 |

9.7 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018–19, Table 11.3 Smoker status by age, sex and Indigenous status, persons aged 15 years and over, 2017–18 and 2018–19, Proportion of persons

* Proportion has a relative standard error between 25 per cent and 50 per cent and should be used with caution

There has been a significant increase in Aboriginal young people not smoking over the last 25 years. In 1994, 70.3 per cent of Aboriginal young people aged 15–17 years did not smoke; by 2018–19 this had increased to 88.2 per cent.

|

1994 |

2002 |

2008 |

2012-13 |

2014-15 |

2018-19 |

|

|

Male |

68.2 |

65.8 |

79.5 |

78.3 |

75.2 |

84.8 |

|

Female |

72.4 |

67.6 |

76.2 |

84.0 |

87.9 |

91.4 |

|

Total |

70.3 |

66.7 |

77.9 |

81.0 |

82.6 |

88.2 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4737.0 - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Smoking Trends, Australia, 1994 to 2014-15 and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018–19

Proportion of Aboriginal young people aged 15 to 17 years not smoking by gender, per cent, Australia, 1994 to 2018–19

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4737.0 - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Smoking Trends, Australia, 1994 to 2014-15 and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018–19

In general, male Aboriginal young people are more likely to smoke than female Aboriginal young people, although in 2018–19 the proportion of male Aboriginal young people not smoking increased.

Aboriginal young people in remote locations are much more likely to smoke than those in non-remote locations (24.4% in remote locations compared to 10.6% in non-remote locations in 2018–19).10

E-cigarettes

Use of e-cigarettes (vaping) is increasing amongst Australian young people.11 E-cigarettes are devices which aerosolise nicotine or other chemicals which are then inhaled by the user. The liquid solution can be nicotine or THC (a cannabis-based product) or other flavoured solutions.12 THC is illegal in Australia and nicotine is illegal for e-cigarettes.13

In 2019, nearly two-thirds (63.9%) of current smokers aged 18 to 24 years and one-in-five (19.7%) non‑smokers aged 18 to 24 years reported having tried e-cigarettes.14

More data and research is required on the use of e-cigarettes.

Education about tobacco smoking

In SOS19, young people in Years 7 to 12 were asked how much they have learnt about smoking at school. Most (70.6%) young people reported that they had learnt a lot (34.2%) or some (36.4%) about smoking tobacco at school. While, 20.0 per cent reported they had only learnt a little bit and 9.3 per cent reported they had learnt nothing.15

Most (90.6%) high school students reported that they feel like they know enough about the health impacts of smoking, while 5.3 per cent did not feel like they knew enough and 4.1 per cent were not sure.16

Students in remote locations are more likely than those in metropolitan Perth to report that they had learnt a lot about smoking at school (46.1% compared to 32.3%). In spite of this, students in remote locations are less likely to feel like they know enough about the health impacts of smoking than students in the metropolitan region (84.8% compared to 91.6%).17

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex children

For information on LGBTI young people’s consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Culturally and linguistically diverse young people

For information on culturally and linguistically diverse young people’s consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Young people in the youth justice system

For information on the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs of young people in youth detention refer to the Measure: Use of illicit drugs.

Endnotes

- Office of the Surgeon General (US) 2004, The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (US), p. 1.

- Khuder et al 1999, Age at smoking onset and its effect on smoking cessation, Addictive behaviours, Vol 24, no 5, p. 95.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table S.9: Daily tobacco smoking status, by age and state/territory, 2007 to 2019, AIHW.

- Guerin N and White V 2018, ASSAD 2017 Statistics & Trends: Australian Secondary Students’ Use of Tobacco, Alcohol, Over-the-counter Drugs, and Illicit Substances, Cancer Council Victoria, p. 15.

- Ibid, p. 16.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 8.1: Use of drugs by Indigenous status, people aged 14 and over, 2010 to 2019 (col per cent), AIHW.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19, Summary results for states and territories (fact sheets), ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Australia, 2018–19, Table 12.3 Smoker status by age, sex and remoteness, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons aged 15 years and over, 2004–05 to 2018–19, ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Drug Statistics series no 32, PHE 270, AIHW, p. 10.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Healthy WA 2021, Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), WA Government [website].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 2.19: Lifetime use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), by age and smoker status and Table 2.20: Lifetime use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), current smokers, AIHW.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Last updated August 2021

Illicit drug use is a major cause of preventable disease and illness in Australia. In 2010, WA residents were hospitalised 5,644 times for conditions related to drug use, costing approximately $30m.1

Of all jurisdictions in Australia, WA had the highest rate of unintentional drug-induced deaths in 2018. Furthermore, the rate of unintentional drug-induced deaths in WA increased from 6.4 per 100,000 in 2012 to 8.8 per 100,000 in 2018.2

Aside from the considerable health and behavioural problems associated with illicit drug use, children and young people are at particular risk of harm from drug use, as it negatively impacts the development of neurological pathways and is strongly associated with long-term drug dependency issues.3

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing. In this survey some specific questions were asked of Year 9 to Year 12 students about experiences with illicit drugs.

Overall, over one-quarter (28.4%) of young people in Year 9 to Year 12 have had experiences with marijuana. This may include own use as well as use by others, such as friends or family members.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

No |

69.2 |

67.1 |

70.0 |

58.8 |

66.0 |

68.2 |

|

Yes |

27.3 |

29.5 |

26.7 |

37.2 |

28.3 |

28.4 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

5.7 |

3.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 9 to Year 12 students reporting whether they have ever had any experiences with marijuana by various characteristics, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Due to the small sample size, differences are not statistically significant, however a greater proportion of young people in regional locations reported that they had experiences with marijuana than in remote and metropolitan areas (37.2% compared to 28.3% and 26.7%).

Of further concern is that one-quarter (26.1%) of Year 10 to Year 12 students thought it was okay for someone their age to use marijuana (compared to 8.2% of Year 7 to Year 9 students). In contrast, fewer (12.7%) Year 10 to Year 12 students thought it was ok for someone their age to smoke tobacco. Additionally, 60.0 per cent of Year 10 to Year 12 students reported that they had friends who used marijuana.4

Overall, more than one in ten (13.4%) young people in Year 9 to Year 12 had had experiences with other drugs (excluding tobacco, alcohol or marijuana).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

No |

83.5 |

84.8 |

85.7 |

75.7 |

81.4 |

84.1 |

|

Yes |

14.5 |

12.1 |

12.2 |

20.3 |

12.0 |

13.4 |

|

Prefer not to say |

2.0 |

3.1 |

2.1 |

4.0 |

6.6 |

2.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Similar to experiences with marijuana, Year 9 to Year 12 students in regional locations were more likely to report that they had had experiences with other drugs than students in metropolitan or remote locations (20.3% compared to 12.2% and 12.0%). There were no differences between male and female students.

Two in five (39.7%) Year 10 to Year 12 students reported that they had friends who used other drugs.5

At the same time, 84.2 per cent of Year 7 to Year 9 students and 59.5 per cent of Year 10 to Year 12 students think young people their age should not use alcohol or other drugs, including tobacco and marijuana.6

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) is a triennial survey that in 2019 collected information from approximately 23,000 people across Australia. In this survey participants were asked about their drug use patterns, attitudes and behaviours.7

The NDSHS shows a reduction in Australian young people aged 14 to 17 years using illicit drugs from 2010 to 2019 (14.5% of young people in 2010 to 9.7% of young people in 2019).8

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reports NDSHS data by jurisdiction, however it has a very high relative standard error and has not been reproduced here. The high sampling error across almost all jurisdictions in recent years is of concern, this suggests that the sample sizes were not sufficient to provide valid and reliable estimates for this critical age group by jurisdiction.

The Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug (ASSAD) survey is a triennial national survey of secondary students’ use and attitude towards licit and illicit substances. The 2017 survey included 3,361 WA young people aged from 12 to 17 years from 46 randomly selected government, Catholic and independent schools across the state.9

The following has been produced by the Mental Health Commission reporting WA results from the 2017 ASSAD survey.

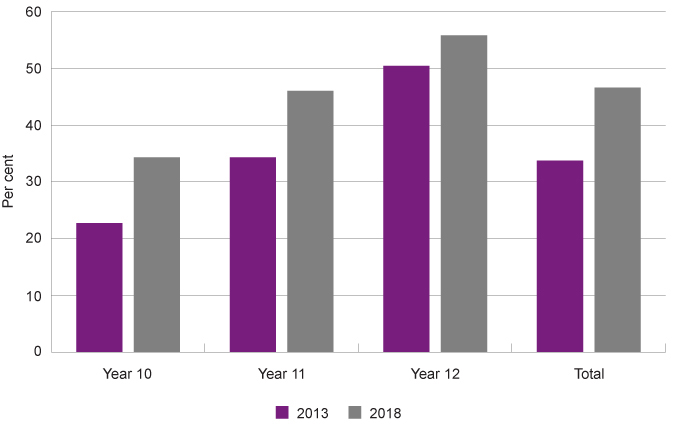

In 2017, less than one in five (18.1%) WA students aged 12 to 17 years reported ever using one illicit drug (including marijuana/cannabis), in comparison to more than two in five (40.7%) students in 1996.10

|

Lifetime |

Past year |

Past month |

Past week |

|

|

1996 |

40.7 |

36.6 |

24.2 |

16.5 |

|

1999 |

39.7 |

34.2 |

21.6 |

13.8 |

|

2002 |

32.7 |

27.8 |

16.5 |

10.4 |

|

2005 |

23.7 |

19.4 |

10.4 |

5.7 |

|

2008 |

19.1 |

16.4 |

8.6 |

5.5 |

|

2011 |

18.6 |

16.4 |

9.5 |

5.9 |

|

2014 |

18.5 |

16.5 |

10.1 |

6.5 |

|

2017 |

18.1 |

16.1 |

9.6 |

5.6 |

Source: Mental Health Commission, Illicit drug trends in Western Australia: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, Figure 1: Trends in the use of at least one illicit drug, 1996 - 2017

Prevalence and recency of illicit drug use for students aged 12 to 17 years, per cent, WA, 1996 to 2017

Source: Mental Health Commission, Illicit drug trends in Western Australia: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, Figure 1: Trends in the use of at least one illicit drug, 1996 - 2017

The majority of this decline is due to a reduction in cannabis (marijuana) consumption. Cannabis was the primary illicit drug used by WA young people in 1996, with 39.7 per cent of WA young people in 1996 using cannabis in their lifetime.11 This has reduced to 16.8 per cent of WA young people in 2017.12

There has been a significant decrease in the proportion of young people who had used illicit drugs from 1996 to 2017 in the past year (36.6% to 16.1%), past month (24.2% to 9.6%) and past week (16.5% to 5.6%).13

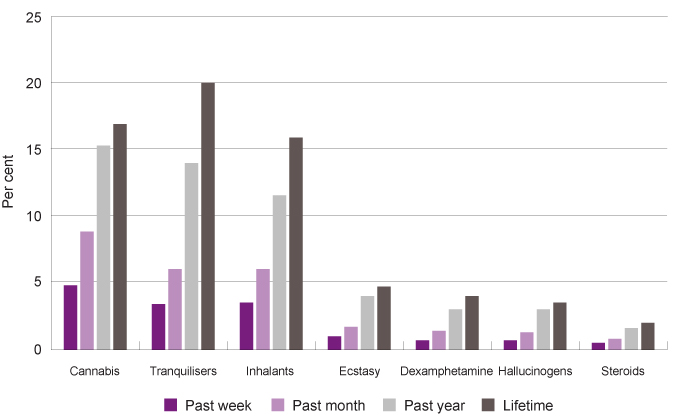

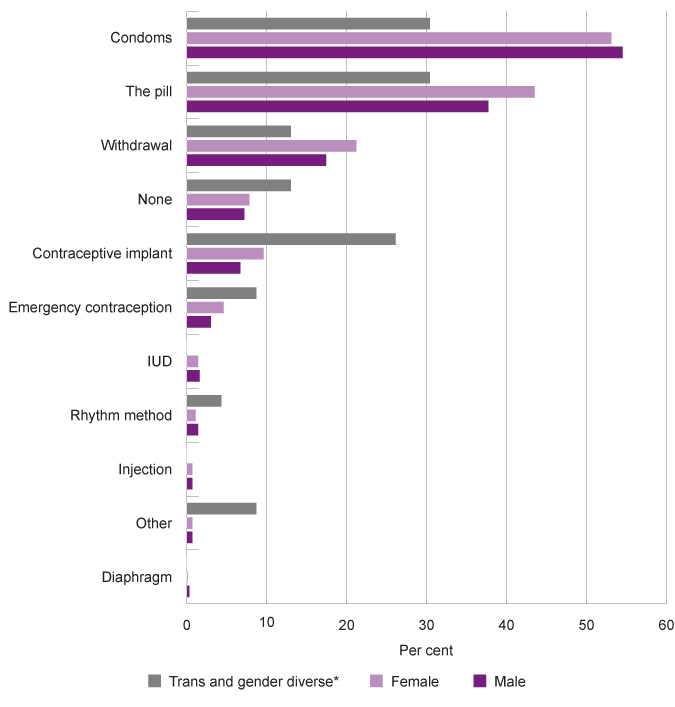

The most commonly used drugs in 2017 among WA young people aged 12 to 17 years in the past year were cannabis (15.2% of all WA 12 to 17 year-olds), tranquilisers (13.9%) and inhalants (11.5%). Tranquilisers include sleeping tablets, sedatives and benzodiazepines, such as Valium, Temazepam and Serepax. While inhalants include substances that are sniffed such as glue, paint or spray cans.

|

Past week |

Past month |

Past year |

Lifetime |

|

|

Cannabis |

4.8 |

8.8 |

15.2 |

16.8 |

|

Tranquilisers* |

3.4 |

6.0 |

13.9 |

19.9 |

|

Inhalants |

3.5 |

6.0 |

11.5 |

15.8 |

|

Ecstasy |

1.0 |

1.7 |

4.0 |

4.7 |

|

Dexamphetamine* |

0.7 |

1.4 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

|

Hallucinogens |

0.7 |

1.3 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

|

Steroids* |

0.5 |

0.8 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

|

Cocaine |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

|

Meth/Amphetamines |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

Source: Mental Health Commission, Illicit drug trends in Western Australia: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, Figure 2: Prevalence and recency of illicit drug use for students

* Non-medical use

Prevalence and recency of use of most common illicit drugs for secondary students aged 12 to 17 years, per cent of students, WA, 2017

Source: Mental Health Commission, Illicit drug trends in Western Australia: Australian school students alcohol and drug survey, Figure 2: Prevalence and recency of illicit drug use for students

In the 2017 survey, 65 per cent of young people who used tranquilisers for non-medicinal purposes reported sourcing them from their parents, however, this may include incorrectly reported prescribed use.14

There is limited data comparing WA young people’s drug use to other states or Australia. The data in the below table has been collated from the ASSAD survey in 2017, showing similar results for WA and Australia.

|

Past month |

Lifetime |

|||

|

WA |

Australia |

WA |

Australia |

|

|

Cannabis |

8.8 |

8.0 |

16.8 |

17.0 |

|

Tranquilisers* |

6.0 |

6.0 |

19.9 |

20.0 |

|

Inhalants |

6.0 |

8.0 |

15.8 |

18.0 |

|

Ecstasy |

1.7 |

2.0 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

|

Dexamphetamine* |

1.4 |

1.0 |

4.0 |

2.0 |

|

Hallucinogens |

1.3 |

1.0 |

3.5 |

4.0 |

|

Steroids* |

0.8 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

|

Cocaine |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

|

Meth/amphetamines |

0.6 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

2.0 |

Source: Mental Health Commission, Illicit drug trends in Western Australia: Australian school students’ alcohol and drug survey, and National Drug Strategy, Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2017

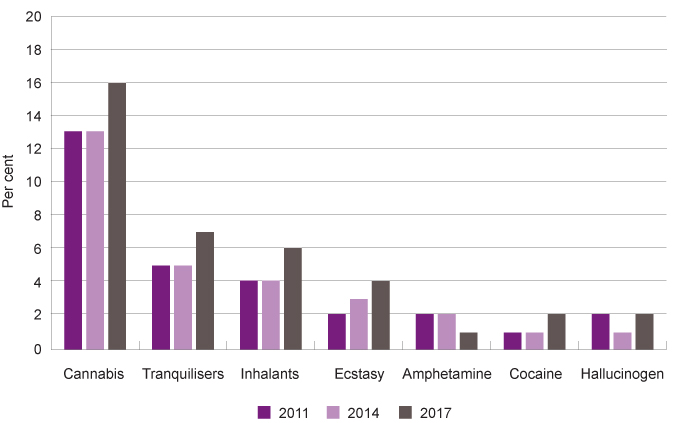

For each of the most common illicit drugs, except inhalants, Australian young people aged 16 to 17 years are more likely to have used drugs in the past month than young people aged 12 to 15 years.

|

12 to 15 years |

16 to 17 years |

|||||

|

2011 |

2014 |

2017 |

2011 |

2014 |

2017 |

|

|

Cannabis |

4.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

13.0# |

13.0 |

16.0 |

|

Tranquilisers |

4.0# |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0# |

5.0 |

7.0 |

|

Inhalants |

8.0 |

7.0 |

8.0 |

4.0# |

4.0# |

6.0 |

|

Ecstasy |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

2.0# |

3.0 |

4.0 |

|

Amphetamine |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

|

Cocaine |

<1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

|

Opiate |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Hallucinogen |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

|

Steroids |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

Source: National Drug Strategy, Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2017

# Significantly different from the 2017 result

Young people aged 16 to 17 years, use of most common illicit drugs in the past month, per cent, Australia, 2011, 2014 and 2017

Source: National Drug Strategy, Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2017

The above age breakdown is not published for WA young people, although it is likely the trends will be similar.

Data for Australian young people aged 16 to 17 years highlights a recent increase in usage of the most common drugs, except amphetamine, from 2014 to 2017.15 These results will continue to be monitored to determine if they represent an ongoing trend.

Interestingly, amphetamine use has been decreasing for high school students in WA since 2002.16 These statistics contrast with concerns surrounding a current ‘ice epidemic’ in Australia. Data shows that while across Australia there has not been an increase in users of amphetamines (including ‘speed’ and ‘ice’), there has been an increase in hospitalisations related to methamphetamine use.17 Research suggests that existing amphetamine users are switching from ‘speed’ to ‘ice’, which is a purer form of amphetamine that causes more harm.18 It is believed that this is because price reductions have increased the availability of methamphetamine with higher purity, which is more harmful.19,20

The 2017 ASSAD survey shows that Australian male young people aged 12 to 17 years are slightly more likely to use illicit drugs (including non-prescribed tranquilisers) than female young people, although in the case of most drugs there was minimal difference.21

The NDSHS collects information on the factors that influence young people to use an illicit drug.

|

2013 |

2016 |

2019 |

|

|

To see what it was like/curiosity |

70.7 |

64.3 |

65.7 |

|

Friends or family member were using it/ offered by friend or family member |

39.4 |

45.0 |

49.0 |

|

To do something exciting |

30.3 |

22.1 |

24.6 |

|

Thought it would improve mood/to stop feeling unhappy |

20.9 |

17.8* |

23.4 |

|

To enhance an experience |

11.5* |

17.9* |

16.2* |

|

Other |

3.2** |

4.7** |

3.4** |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019, Table 4.22: Factors influencing first use of an illicit drug, people who have used an illicit drug in their lifetime(a), by age and use status, 2013 to 2019 (per cent)

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

** Estimate has a high level of sampling error (relative standard error of 51% to 90%), meaning that it is unsuitable for most uses.

Note: Respondents could select more than one response.

The most commonly cited reason for Australian young people aged 14 to 17 years to use illicit drugs for the first time was to see what it was like and/or curiosity (65.7%). A significant proportion (49.0%) of young people were also influenced by friends or family who were using it or they were offered it by a friend or family member.

Critically, almost one-quarter (23.4%) of Australian young people aged 14 to 17 years took illicit drugs for the first time because they thought it would improve their mood or stop them feeling unhappy.

There was no further disaggregation by gender, Aboriginal status or geographic location for this data.

Aboriginal young people

In SOS19, a significantly lower proportion of Aboriginal students than non-Aboriginal students reported not having had experiences with marijuana (55.6% compared to 68.8%).

It should be noted that experiences with a drug will often include being around people who are using the drug at a party, gathering or at home.

|

Experiences with marijuana |

Experiences with other drugs |

|||

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

No |

55.6 |

68.8 |

78.8 |

84.3 |

|

Yes |

34.9 |

28.0 |

15.0 |

13.3 |

|

Prefer not to say |

9.5 |

3.2 |

6.2 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Similar proportions of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people reported having had experiences with other drugs.

The results are not statistically significant, but marginally higher proportions of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal young people reported thinking it is okay for someone their age to use cigarettes/tobacco or other drugs.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Cigarettes, tobacco |

11.8 |

7.9 |

|

Alcohol |

18.4 |

17.9 |

|

Marijuana |

17.3 |

16.6 |

|

Other drugs |

10.4 |

7.1 |

|

None |

72.1 |

72.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Note: the students were able to choose as many as they needed.

There is limited data on Aboriginal young people’s use of illicit or other drugs. However, the data suggests that illicit drug use is similar among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people.

In 2020, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released results for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (NATSIH) Survey. Based on this survey, in 2018–19, 32.9 per cent of Aboriginal people aged 15 to 29 years had used a drug for non-medical purposes in the last 12 months.22 This survey does not report separately on Aboriginal children and young people.

The NDSHS reports that in 2019, a similar proportion (31.2%) of 18 to 24 year old Australian young people have recently used illicit drugs.23

In the NATSIH Survey, drug use is sustained at 31.0 per cent for Aboriginal people aged 30 to 44 years. While, in the NDSHS, drug use for 30 to 39 year-old Australians decreases to 19.1 per cent. 24,25

Therefore, while illicit drug use is estimated to be similar among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people, the data shows that Aboriginal people continue using into adulthood at higher levels than non-Aboriginal people. This is related to the burden of inter-generational trauma, disconnection from communities, cultural values and traditions as a result of the ongoing effects of colonisation.26

Aboriginal people are also more likely than non-Aboriginal people to experience significant life stressors. For example, in the ABS Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, Aboriginal young people aged 15 to 24 years are more likely than non-Aboriginal young people to have experienced a death of a family member (30.9% compared to 21.1%) and been unable to get a job (24.3% compared to 11.7%).27

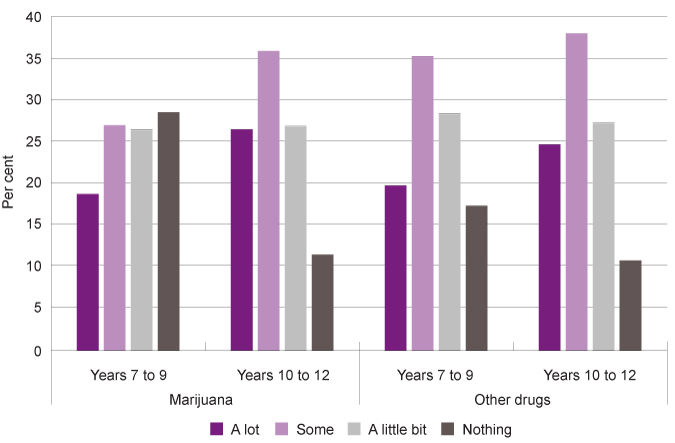

Education about marijuana and other illicit drugs

In SOS19 students in Year 7 to Year 12 were asked how much they have learnt about marijuana and other drugs at school.

Almost one-half (46.9%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they had learnt a little bit (26.5%) or nothing (20.4%) about marijuana at school. This is in contrast to the proportion of students who reported learning a little bit or nothing about alcohol (23.0%) and smoking (29.4%).

Students in Years 10 to 12 had learnt more than students in Year 7 to 9 about marijuana at school, but a significant proportion (38.1%) of older students still reported they had learnt a little bit (27.1%) or nothing (10.7%).

Similarly, a large proportion (41.8%) of students in Year 7 to Year 12 had learnt a little bit (27.7%) or nothing (14.1%) about other drugs at school.

|

Marijuana |

Other drugs |

|||||

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

All |

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

All |

|

|

A lot |

18.6 |

26.3 |

22.2 |

19.6 |

24.5 |

21.9 |

|

Some |

26.8 |

35.6 |

30.9 |

35.0 |

37.7 |

36.3 |

|

A little bit |

26.3 |

26.7 |

26.5 |

28.2 |

27.1 |

27.7 |

|

Nothing |

28.3 |

11.4 |

20.4 |

17.2 |

10.7 |

14.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting how much they have learnt about marijuana and other drugs at school by year group, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Thus, although more students are learning about marijuana and other drugs as they move through school, a significant proportion are not learning very much even by the time they reach Years 10 to 12.

Notably, one in five (21.9%) Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they did not feel like they knew enough about the health impacts of marijuana and 12.5 per cent were not sure. That is, one-third (34.4%) of WA high school students do not feel like they know enough (or are not sure) about the health impacts of marijuana.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

No |

18.9 |

25.4 |

23.4 |

15.1 |

16.6 |

21.9 |

|

Yes |

71.9 |

59.1 |

64.6 |

72.0 |

64.6 |

65.6 |

|

I'm not sure |

9.3 |

15.6 |

12.0 |

12.9 |

18.8 |

12.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A greater proportion of female students than male students did not feel like they knew enough or were not sure about the health impacts of marijuana (41.0% compared to 28.2%).

Similarly, 29.1 per cent of students in Year 7 to Year 12 reported that they do not feel like they know enough or are not sure about the health impacts of other drugs.28

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students reported similar experiences of learning about drugs at school and feeling like they know enough about the health impacts.29

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex young people

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI)30 children and young people are at an increased risk of the consumption of tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs

Having a diverse sexual orientation, diverse gender identity, or being intersex are not in themselves risk factors for tobacco use, alcohol consumption or illicit drug use. However, the issues that affect LGBTI people such as social and cultural beliefs and assumptions about gender and sexuality, including systemic discrimination at an individual, social, political and legal level mean that young people within this group may use alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs as a form of self-medication.31

The 2019 NDSHS reported relatively high rates of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use among same sex attracted or bisexual participants aged 14 years and older (including adults). Same-sex attracted/bisexual respondents were more likely to consume alcohol on a single occasion at least monthly at levels that were risky (35.4% of same-sex attracted/bisexual participants compared to 26.1% of heterosexual participants) and more likely to smoke tobacco on a daily basis (16.7% compared to 10.8%).32

Furthermore, almost two in five (36.0%) same-sex attracted/bisexual respondents reported that they had recently used an illicit drug, compared to 16.1 per cent of heterosexual respondents. The most common illicit drugs recently used by same-sex attracted/bisexual respondents were cannabis (25.9%), inhalants (9.9%), cocaine (8.0%) and ecstasy (7.4%).33 The NDSHS does not provide data for same-sex attracted/bisexual young people or LGBTI young people, more broadly.

In 2019, La Trobe University conducted the Writing themselves In 4 national survey with 6,418 LGBTI young people aged 14 to 21 years.34 The study does not report on a representative sample of the LGBTI community in Australia, however does provide valuable insights into the experiences of young people within the LGBTI community.

This survey found that less than one-half (47.7%) of participants aged 14 to 17 years reported drinking alcohol, which the authors note is a lower proportion than in the general population. Further, the study reported that 85.2 per cent of LGBTI young people aged 14 to 17 years had never smoked, while 11.5 per cent currently smoke. Again, this is lower than the general population for that age group.35

This survey found that LGBTI young people reported much lower levels of alcohol and tobacco smoking than in the previous 2010 Writing themselves In 3 survey.36

In contrast, the participants did report higher levels of illicit drug use than the non-LGBTI young people, with over one-quarter (26.5%) of LGBTI young people aged 14 to 17 years reported using drugs for non-medicinal purposes in the past six months,37 compared to the NDSHS which found that 9.7 per cent of young people aged 14 to 17 years had used an illicit drug in the previous 12 months.38

The most commonly used drug (for non-medicinal purposes) by LGBTI young people aged 14 to 17 years was cannabis (22.2%) followed by anti-depressants (5.0%).39

Male young people (both trans and cisgender) were more likely to use illicit drugs than female trans and cisgender young people.40

For more information on LGBTI children and young people, refer to the Commissioner’s 2018 issues paper: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) children and young people.

Culturally and linguistically diverse young people

Some children and young people from CALD backgrounds (and their families) experience language barriers, feeling torn between cultures, intergenerational conflict, racism and discrimination, bullying and resettlement stress.41 Refugee young people are at a higher risk of substance misuse due to dealing with loss, trauma, settlement issues, low socioeconomic status, family breakdowns, intergenerational conflict, youth unemployment, difficulties in school, peer influence, desire for acceptance and the lack of culturally appropriate social and recreational activities.42,23

Data and research also suggests that people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds often do not seek help for mental health issues.44 For some, the use of legal and illicit drugs can be a way of coping with these challenges.45 However, there are many protective factors that assist in reducing substance misuse within the CALD and refugee community. These protective factors include spiritual beliefs, cultural norms, and strong community connections.46

There is limited data on substance misuse of CALD young people, however the data that is available suggests that across all age groups they are less likely to consume alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs than other Australian people.

The 2019 NDSHS compared the proportion of drug use between English and language other than English (LOTE) speakers aged 14 years and older (including adults).47 The data highlights that a low proportion of LOTE participants (6.2%) are daily smokers in comparison to English speaking participants (11.8%).48 Similarly, 52.9 per cent of LOTE Australians did not drink alcohol, compared to 19.2 per cent of non-LOTE Australians. While, 82.6 per cent of LOTE Australians had never used an illicit drug compared to 51.6 per cent of non-LOTE Australians.49

For more information on CALD children and young people and their wellbeing concerns, refer to the Commissioner’s 2016 ‘This is Me’ paper: Stories from culturally and linguistically diverse children and young people.

Young people in the youth justice system

Children and young people in the youth justice system are more likely to have mental health issues which increases the risk of substance use.50 The Banksia Hill Detention Centre is the only facility in WA for the detention of children and young people 10 to 17 years of age who have been remanded or sentenced to custody.

During 2019–20, approximately 107 children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years were held in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre in WA on an average day.51

In their 2021 inspection of the Banksia Hill facility, the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services noted that although the young people entering the centre were often drug-affected, alcohol and other drug counselling services were not available because federal funding had been cut.52

Children and young people entering youth detention have the right to be assessed to determine whether they have a physical or intellectual disability, mental health issues, alcohol and other drug issues or experience other forms of vulnerability and to have those needs met.

No data is available on alcohol, tobacco or illicit drugs consumption of WA young people in the youth justice system.

In 2015 the Young People in Custody Health Survey (YPICHS) was conducted in NSW across seven juvenile justice centres. Of the young people invited to participate, 90.4 per cent completed the survey which represented 59.3 per cent of young people in custody at the time across NSW.53

Results from this survey highlighted an overwhelming majority of young people in custody smoked tobacco. Over nine in ten (92.0%) survey participants reported that they had smoked in their lifetime, and four in five participants (85.4%) stated that they had smoked in the last 12 months.54 There were no significant differences in gender or Aboriginality among those who had reported smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day, however, the mean age of smoking initiation among Aboriginal young people was significantly earlier than non-Aboriginal young people (11.7 years and 12.7 years respectively).55

These results are in contrast to the broader population of Australian young people aged 12 to 17 years where 83.0 per cent have never smoked,56 and the average age of initiation was around 16 years of age.57

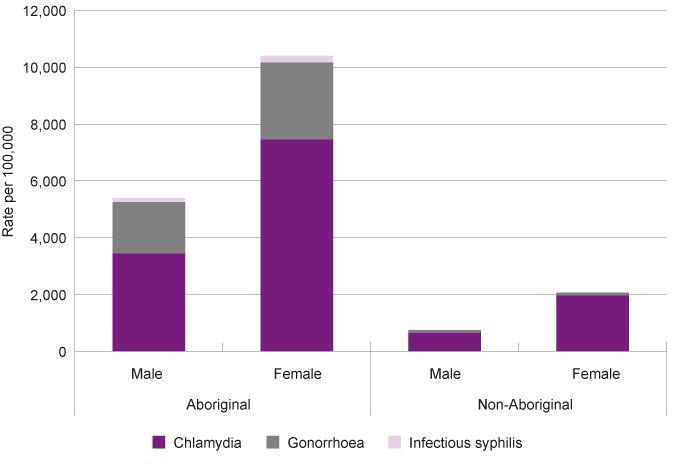

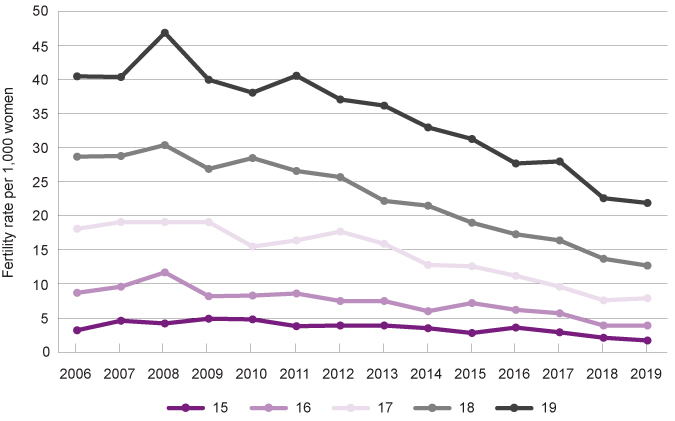

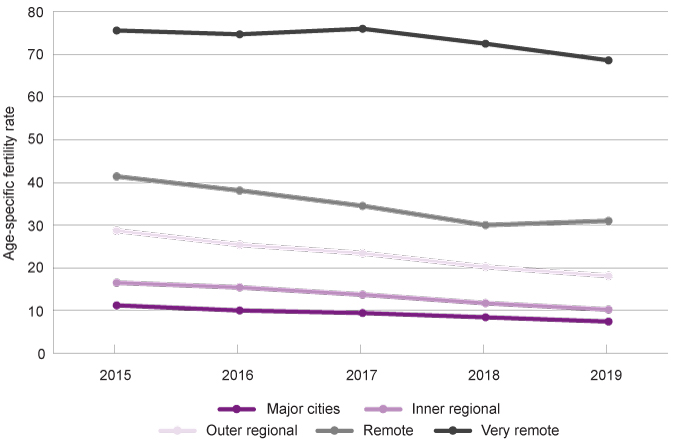

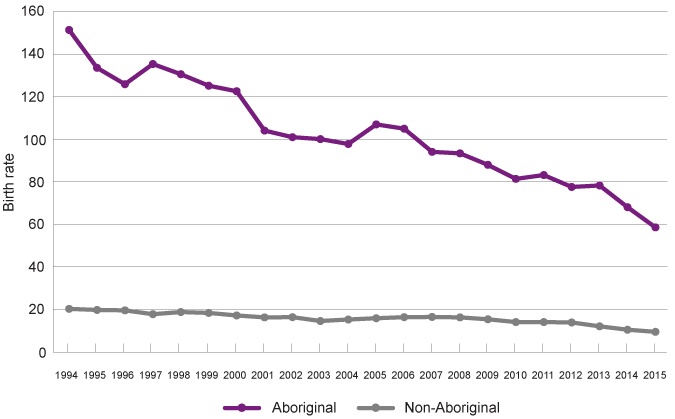

Alcohol consumption in the lifetime of the young people in custody was reportedly over nine in ten participants (93.4%), and of those young people, 96.7 per cent had experienced being drunk, with no gender or Aboriginality differences.58 Age of initiation of a young person’s first full serve of alcohol did not differ between male and female young people (13.1 years and 13.4 years), however Aboriginal young people reported initiation at a significantly earlier age (12.7 years).59 Two in five young people who participated in the survey reported getting drunk weekly prior to custody and just over half of the young people had stated that drinking alcohol had contributed to problems with school, health, friends and family.60