Mental health

Good mental health is an essential component of wellbeing and means that young people are more likely to have fulfilling relationships, cope with adverse circumstances and adapt to change.

Poor mental health is associated with behavioural issues, a diminished sense of self-worth and a decreased ability to cope. This has adverse effects on a young person’s quality of life, emotional wellbeing and relationships as well as their capacity to engage in school and other activities.1

Last updated July 2020

Some data is available on whether WA young people aged 12 to 17 years are mentally healthy.

Overview

This indicator reports on a number of key measures that track whether young people in WA are mentally healthy. These includes the measures that consider the prevalence of mental health issues for young people aged 12 to 17 years and measures that report mental health service use by young people in WA. This indicator also considers incidences of self-harm and suicide.

Key risk factors for mental health issues in young people include family socio-economic disadvantage, parental mental health, child temperament, bullying, experience of domestic violence, abuse or a traumatic event.1,2,3,4

There is limited reliable data which accurately reflects the prevalence of mental health issues for young people in WA.

Areas of concern

Limited data is available to assess whether mental health outcomes for WA young people aged 12 to 17 years have improved as a result of any changes in mental health service provision and investment.

Female young people in WA rate their mental health much less favourably than their male peers with 69.9 per cent of female Year 9 to 12 students reporting a recent episode of feeling sad, blue or depressed (compared to 49.7% of male students).

Suicide is the main cause of preventable deaths for WA young people.

Over 2014 to 2018, the age-specific death rate due to intentional self-harm for WA Aboriginal children and young people aged five to 17 years (17.0 per 100,000) was almost nine times higher than non-Aboriginal WA children and young people (2.0 per 100,000).5

Research shows that young people in care are significantly more likely to have mental health issues than other young people,6 yet there is no data publicly available on the mental health of young people in care in WA or the provision of mental health services to these young people.

Endnotes

- Christensen D et al 2017, Longitudinal trajectories of mental health in Australian children aged 4-5 to 14-15 years, PLoS ONE, Vol 12, No 11.

- Center on the Developing Child 2018, Toxic Stress, Harvard University [website].

- Moore S et al 2017, Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis, World Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 7, No 60.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) 2015, Children's exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses: CFCA Paper No. 36 – December 2015, AIFS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 3303.0 - Causes of Death, Australia, 2018, Intentional Self-Harm in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, ABS.

- Sawyer M et al 2007, The mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in home-based foster care, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 186, No 4.

Last updated July 2020

Research shows that an optimistic or positive outlook on life is a protective factor for mental health issues, in particular anxiety and depression.1 It is generally recognised that children, young people and adults have a particular ‘attribution style’ or disposition towards optimism or pessimism which influences the way they interpret events that happen in their lives.2,3 Research also suggests that it is possible to adjust a person’s disposition towards a more positive frame through targeted interventions including therapy.4,5

A positive outlook is also important for young people as they develop their identity and imagine their future selves. Research suggests that having the ability to imagine a positive version of a future self is linked to better health and educational outcomes, including reduced drug use, less sexual risk-taking behaviours and less involvement in violence.6

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions about their view of themselves.7

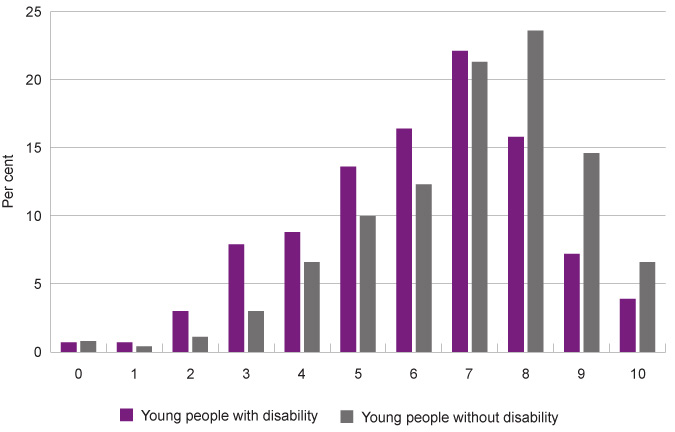

The survey asked students to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 where they felt their life was from the worst (0) to the best (10) possible life.

Average ratings were lower for students in Years 10 to 12 than in Years 7 to 9 and 4 to 6 (6.5 in Years 10 to 12 compared to 7.1 in Years 7 to 9 and 7.8 in Years 4 to 6).8

With respect to grouped ratings (0 to 4, worst; 5 or 6; and 7 to 10, best), over 60 per cent (62.3%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students rated their life as the best possible. At the same time, 14.3 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students rated their life as the worst possible (rating of 0 to 4).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Total |

||

|

7 to 10 |

71.2 |

53.5 |

61.3 |

65.0 |

70.4 |

62.3 |

|

5 to 6 |

17.8 |

29.2 |

24.0 |

22.2 |

16.9 |

23.4 |

|

0 to 4 |

11.1 |

17.3 |

14.7 |

12.8 |

12.7 |

14.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A significantly lower proportion of young people in Years 10 to 12 rated their life as the best possible (55.1%) compared to young people in Years 7 to 9 (68.7%).

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

7 to 10 |

68.7 |

55.1 |

|

5 to 6 |

19.2 |

28.1 |

|

0 to 4 |

12.1 |

16.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Similarly, over one-third (34.5%) of Year 10 to Year 12 students disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement ‘I am happy with myself’ (compared to 21.5% of Year 7 to Year 9 students).9

The lower sense of life satisfaction and wellbeing of students in Years 10 to 12 is likely related to an increase in stress due to study pressure. For students in Years 9 to 12 school or study problems were the most frequently reported source of stress with 84.5 per cent of students saying they were affected by this.10 This question was not asked of younger students.

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly less likely to rate their life as the best possible compared to male Year 7 to Year 12 students (53.5% compared to 71.2%). This is a substantial decline from primary school with 75.9 per cent of Year 4 to Year 6 female students rating their life as the best possible.11

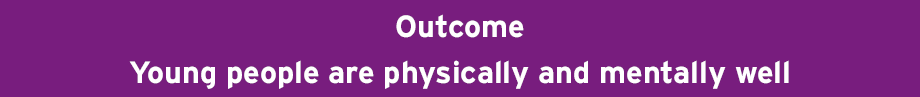

Similarly, more than one-third (38.2%) of female Year 7 to Year 12 students disagreed that they were happy with themselves (compared to 17.1% of male students).

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Strongly agree |

27.8 |

15.3 |

21.6 |

|

Agree |

55.1 |

46.5 |

50.7 |

|

Disagree |

14.1 |

29.4 |

21.5 |

|

Strongly disagree |

3.0 |

8.8 |

6.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting they strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree that they are happy with themselves by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were also less likely than male students to report that they are able to do things as well as most other people with 28.6 per cent of female students disagreeing or strongly disagreeing compared to 16.8 per cent of male students. Only 20 per cent (19.9%) of female students agreed strongly that they were able to do things as well as most other people compared to 30 per cent (29.6%) of male students.

These results are an indication of a wellbeing gap between female and male students that manifests throughout the results of the 2019 Speaking Out Survey. These findings raise questions that will be subject to further analysis by the Commissioner.

There were no significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students in regards to their life satisfaction ratings (Average for Aboriginal: 6.9 compared to non-Aboriginal: 6.8).

Aboriginal students were generally more positive than non-Aboriginal students in terms of their self-perception. Over three-quarters (77.7%) of Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students strongly agreed or agreed that they were happy with themselves compared to 72.1 per cent of non-Aboriginal students.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Strongly agree |

27.6 |

21.3 |

|

Agree |

50.1 |

50.8 |

|

Disagree |

17.8 |

21.7 |

|

Strongly disagree |

4.4 |

6.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Further analysis of Aboriginal young people’s responses in the Speaking Out Survey 2019 will be conducted by the Commissioner in 2020.

Resilience is also critical for young people as it enables them to cope and thrive in the face of negative events, challenges or adversity. Key attributes of resilience in young people include social competence, a sense of purpose or hope for the future, effective coping style, a sense of self-efficacy and positive self-regard.12

In the Commissioner’s Speaking Out Survey 2019, students in Year 7 to Year 12 were asked a series of questions about their level of resilience and how they are coping with life’s challenges.

Overall, 48.4 per cent of young people in Year 7 to Year 12 agreed and 22.1 per cent strongly agreed they could deal with things that happened in life.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Strongly agree |

26.0 |

18.4 |

22.5 |

19.5 |

24.5 |

22.1 |

|

Agree |

54.1 |

42.7 |

47.7 |

51.7 |

49.2 |

48.4 |

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

14.6 |

26.9 |

21.4 |

17.8 |

18.0 |

20.7 |

|

Disagree |

3.8 |

9.2 |

6.4 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

6.5 |

|

Strongly disagree |

1.5 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

4.2 |

1.0 |

2.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Students in Years 10 to 12 were less likely than Year 7 to Year 9 students to strongly agree that they can achieve their goals even if it is hard (14.9% compared to 22.9%) and that they can keep doing things even if it is hard (20.1% compared to 27.5%).13

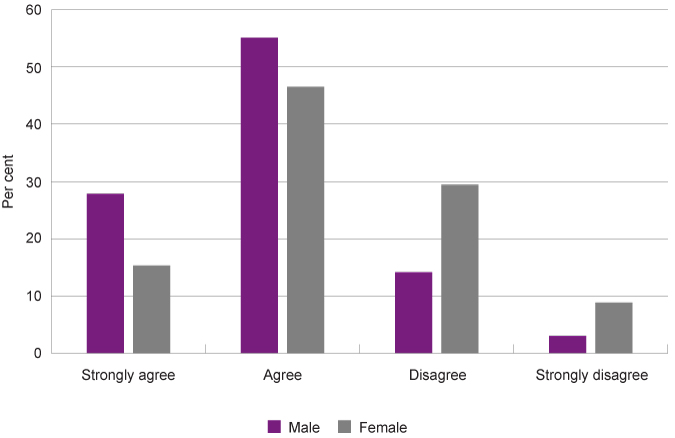

Similar to the responses for other wellbeing questions, female Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly less likely than male students to agree or strongly agree that they can deal with things that happen in their life (61.1% of female students strongly agreed or agreed compared to 80.1% of male students).

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting they strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree or neither agree nor disagree that they can deal with things that happen in their life by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Over one-quarter (26.9%) of female Year 7 to Year 12 students neither agreed nor disagreed that they can deal with things that happen in their life (compared to 14.6% of male students).

There were no significant differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal or metropolitan, regional and remote Year 7 to Year 12 students in regards to their sense of resilience.

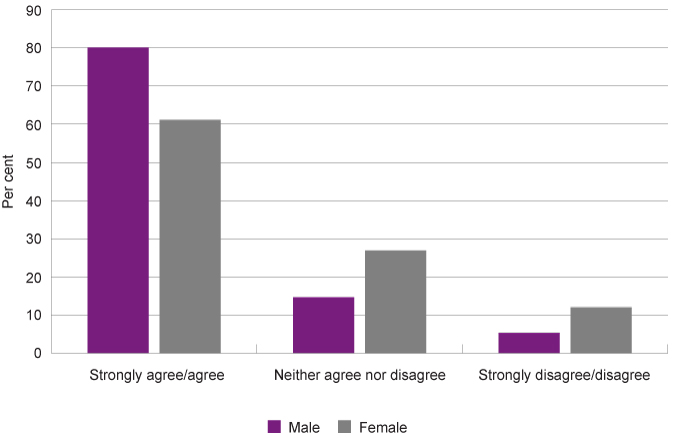

Year 9 to Year 12 students were also asked what has caused them stress in the past year. School and study problems are the single most common source of stress for students in Years 9 to 12 with 91.4 per cent of female students and 77.7 per cent of male students report being affected by this.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

School or study problems |

77.7 |

91.4 |

84.9 |

84.9 |

75.6 |

84.5 |

|

Family conflict |

31.1 |

60.1 |

45.1 |

52.7 |

41.6 |

46.1 |

|

Body image |

24.1 |

66.3 |

44.2 |

51.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 9 to Year 12 students selecting multiple response items that were a source of stress for them in the past year, by various characteristics, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Across all listed sources of stress a significantly greater proportion of female students than male students reported being affected with the top three stressors being school or study problems (91.4% compared to 77.7%), body image (66.3% compared to 24.1%) and family conflict (60.1% compared to 31.1%).

There is some evidence to suggest that female young people are more likely to experience anxiety or depression as a result of stressful situations (such as family conflict), while male young people are more likely to have problems with anger and engage in challenging behaviour.14

A lower, but still substantial, proportion of Year 9 to Year 12 students selected bullying (13.6%) or personal safety (12.2%) as a source of stress in the past year. Personal safety was of greater concern to female students (15.5% female compared to 8.1% male), while there was no significant difference between genders regarding bullying as a source of stress.

Mission Australia Youth Survey

In the annual Mission Australia 2019 Youth Survey, 25,126 young people across Australia aged 15 to 19 years responded to questions across a broad range of topics including education and employment, influences on post-school goals, housing and homelessness, participation in community activities, general wellbeing, values and concerns, preferred sources of support, as well as feelings about the future.

In total, 2,766 young people from WA aged 15 to 19 years responded to Mission Australia’s Youth Survey 2019.15 Mission Australia recommend caution when interpreting and generalising the results for certain states or territories because of the small sample sizes and the imbalance between the number of young females and males participating in the survey.

More than one-half of WA respondents (50.3%) were male and 45.8 per cent were female. A total of 158 (5.9%) respondents from WA identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.16

In the Mission Australia survey, young people are asked how positive they feel about the future. In 2019, WA young people were slightly less positive than in 2018 (56.2% very positive or positive in 2019 compared to 57.4% in 2018) and less positive than Australian young people overall (WA: 56.2%, Australia: 58.3%).

|

Australia |

WA |

|||||||

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Very positive |

17.3 |

15.8 |

15.5 |

13.3 |

14.3 |

13.5 |

11.6 |

13.0 |

|

Positive |

47.1 |

46.6 |

46.7 |

45.0 |

44.7 |

44.3 |

45.8 |

43.2 |

|

Neither positive or negative |

26.1 |

27.5 |

27.9 |

29.5 |

28.5 |

30.0 |

30.9 |

29.2 |

|

Negative |

6.5 |

7.1 |

6.8 |

8.8 |

7.2 |

8.2 |

7.9 |

9.8 |

|

Very negative |

3.0 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

5.4 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

4.7 |

Source: Mission Australia, Youth Survey Report 2016 to 2019.

Of concern is that almost 15 per cent of respondents aged 15 to 19 years from WA felt negative (9.8%) or very negative (4.7%) about the future.

A much lower proportion of female than male young people aged 15 to 19 years from WA felt positive about the future (51.5% of female young people compared to 61.8% of male young people).

|

Australia |

WA |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

Very positive |

16.3 |

11.3 |

16.2 |

10.1 |

|

Positive |

45.6 |

45.5 |

45.6 |

41.4 |

|

Neither positive or negative |

27.0 |

31.2 |

26.1 |

32.7 |

|

Negative |

7.8 |

9.4 |

7.9 |

11.9 |

|

Very negative |

3.3 |

2.7 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

Source: Mission Australia 2019, Mission Australia Youth Survey Report 2019

Female young people in WA were also less positive about the future than female young people around Australia (WA: 51.5%, Australia: 56.8%).

These results are relatively consistent with the results from the 2019 Speaking Out Survey.

Participants were also asked to rate how happy they were with their life as a whole. While most WA participants were happy with their lives, they were less likely than the Australian average to respond that they were happy or very happy (59.3% compared to 60.7%).

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Happy/very happy |

59.3 |

67.0 |

52.4 |

60.7 |

|

Not happy or sad |

28.6 |

24.9 |

32.9 |

28.2 |

|

Sad/very sad |

12.1 |

8.1 |

14.7 |

11.1 |

Source: Mission Australia 2019, Mission Australia Youth Survey Report 2019

There were differences between male and female responses with only 52.4 per cent of WA female young people stating they were happy or very happy, contrasted with 67.0 per cent of WA male young people. Of concern is that 14.7 per cent of female respondents from WA felt sad or very sad.

Endnotes

- Conversano C et al 2010, Optimism and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Well-Being, Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, Vol 6.

- Seligman M et al 1984, Attributional style and depressive symptoms among children, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol 93, No 2.

- Conversano C et al 2010, Optimism and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Well-Being, Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, Vol 6.

- Roberts CM et al 2018, Efficacy of the Aussie Optimism Program: Promoting Pro-social Behavior and Preventing Suicidality in Primary School Students. A Randomised-Controlled Trial, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol 8.

- MacGowan M and Engle B 2010, Evidence for Optimism: Behavior Therapies and Motivational Interviewing in Adolescent Substance Abuse Treatment, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Vol 19, No 3.

- Johnson SL et al 2014, Future Orientation: A Construct with Implications for Adolescent Health and Wellbeing, International Journal of Adolescent Mental Health, Vol 26, No 4.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Perth, p. 39.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019, The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing – a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 41.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Indicators of wellbeing: 6-11 years Mental Health, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Cahill H et al 2014, Building Resilience in Children and Young People, A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), Youth Research Centre, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, p. 5.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- World Health Organisation (WHO) 2002, Gender and Mental Health, WHO.

- Carlisle E et al. 2019, Youth Survey Report 2019, Mission Australia, p. 192.

- Ibid.

Last updated July 2020

Estimates suggest that approximately three-quarters of adult mental illnesses were diagnosed in adolescence and one-half were diagnosed before 15 years of age.1

Mental health2 issues in children and young people can be caused by multiple inter-dependent factors including a young person’s genetic pre-disposition (e.g. temperament and other health issues such as intellectual disability, ADHD etc.) and their exposure to adverse experiences or environments such as poverty, family breakdown and mental health problems of a parent.3

Young people aged 12 to 17 years often face mental health challenges, including in areas such as sexual health, alcohol and drug use, body image and risk-taking behaviours, that stem from the physical, behavioural, psychological and cognitive changes they are experiencing.4,5

Mental health issues impact young people’s ability to form healthy relationships, participate in learning and cope with adversity. Mental health issues in young people are also associated with impaired social functioning, unemployment, substance abuse and violence.6 In some instances mental illness can lead to psychosocial disability where a person is unable to participate fully in life due to mental ill-health.7

Reliable data that provides information about the extent to which WA young people experience mental health problems and disorders is limited.

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.8 In the survey, students in Years 9 to 12 were asked if during the past 12 months they had ever felt sad, blue or depressed for two weeks or more in a row.

It is important to note that the question used in the survey is not a tool used for diagnosing depression and further research is required to explore the results in more detail.

A majority (60.0%) of students in Years 9 to 12 reported they had felt sad, blue or depressed for two or more weeks in a row in the last 12 months. Female students were significantly more likely than male students to report a recent episode of feeling sad, blue or depressed (69.9% female compared to 49.7% male).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Yes |

49.7 |

69.9 |

60.5 |

60.4 |

50.0 |

60.0 |

|

No |

46.5 |

25.2 |

35.1 |

35.9 |

46.4 |

35.7 |

|

Prefer not to say |

3.8 |

4.8 |

4.5 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

4.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

No significant differences were reported between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students or students in metropolitan, regional and remote areas.

The proportions of students reporting a recent episode of feeling sad, blue or depressed in SOS19 are higher than in other surveys of Australian adolescents,9 additional research is necessary to interrogate these results.

The most comprehensive research on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in WA was the Western Australian Child Health Survey in 1995 and the Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey in 2005. These surveys found that more than one-in-six children aged four to 16 years had a mental health problem10 and almost one-in-four (24%) Aboriginal children aged four to 17 years were at high risk of clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties.11 These surveys have not been repeated.

The 2015 Report on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Young Minds Matter) conducted by the Telethon Kids Institute for the Australian Government provided a comprehensive analysis of the mental health of Australian children and young people aged four to 17 years. Unfortunately, this survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use at the state and territory level or for Aboriginal children and young people.12

The Young Minds Matter survey used a number of diagnostic modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV)13 to assess mental disorders in Australian children and adolescents. Under DISC-IV, disorder status is determined according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Version IV (DSM-IV).14 During the survey, parents and carers completed certain modules of the DISC-IV questionnaire with a trained interviewer, young people aged 11 to 17 years also completed a questionnaire which included the DISC-IV major depressive disorder module.

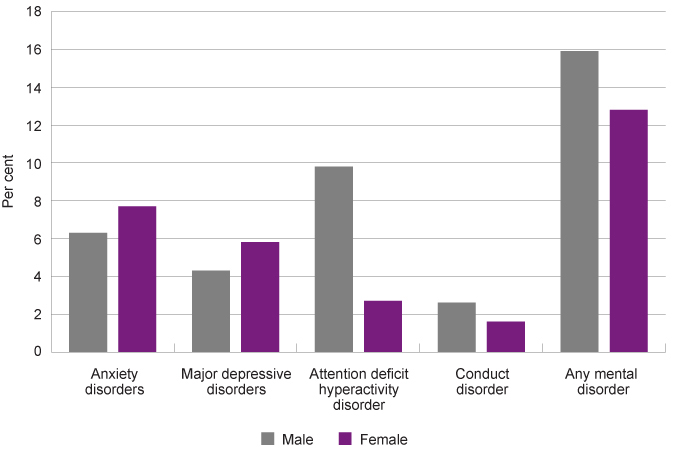

The survey estimated the 12-month prevalence of mental disorders among Australian 12 to 17 year-olds by gender and mental disorder category based on parent/carer responses as outlined in the following table.

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Anxiety disorders |

6.3 |

7.7 |

7.0 |

|

Major depressive disorders |

4.3 |

5.8 |

5.0 |

|

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

9.8 |

2.7 |

6.3 |

|

Conduct disorder |

2.6 |

1.6 |

2.1 |

|

Any mental disorder |

15.9 |

12.8 |

14.4 |

Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

Among young people aged 12 to 17 years, anxiety disorders (7.0%) and ADHD (6.3%) were the most common.15

12-month prevalence of mental disorders among 12 to 17 year-olds, by gender and mental disorder category, based on parent/carer responses, per cent, Australia, 2015

There were differences between male and female young people. Male young people aged 12 to 17 years are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD (9.8% compared to 2.7%) while female young people are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety disorders (7.7% to 6.3%) and major depressive disorders (5.8% compared to 4.3%). It should be noted that research suggests that female children and young people are under‑diagnosed for ADHD, as the symptoms are less overt and often co-exist with different disorders from male children and young people.16,17

Based on young people responses, the estimated 12-month prevalence of some mental disorders among 12 to 17 year-olds differs when compared to the estimates based on parent/carer responses.

Most significantly this is the case for the prevalence of major depressive disorder that is estimated to be higher based on the young people’s responses than parent/carer responses (parent/carer: 4.7%, young people: 7.7%).18

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

11 to 15 years |

3.1 |

7.2 |

5.0 |

|

16 to 17 years |

8.2 |

19.6 |

14.0 |

|

11 to 17 years |

4.5 |

11.0 |

7.7 |

Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

Female young people aged 16 to 17 years were also more than twice as likely to have a major depressive disorder as male young people (19.6% compared to 8.2%). Further, almost double the proportion of female young people aged 16 to 17 years met the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder based on their own responses than on parent/carer responses (19.6% compared to 10.6%).19

These differences between responses from young people and their parents/carers highlight the importance of asking young people about their views, feelings and experiences. These results also suggest that depression in young people, particularly female young people, can go unrecognised by parents and carers.

The WA Department of Health, administers the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, interviewing WA parents and carers of children aged 0 to 15 years.20 In this survey they ask parents and carers about their children’s socio-emotional behaviour and mental health.

In the combined years of 2015 and 2016, WA parents and carers reported that approximately one in 24 children (4.2%) aged six to 15 years had been diagnosed with ADHD. This is similar to the proportion parents and carers reported were diagnosed in 2009-10.21 A comparison to the Young Minds Matter survey which found that 8.2 per cent of four to 11 year olds had ADHD (based on parent/carer reports) highlights that mental health issues can be under-diagnosed in children and young people.

The following table outlines the parent and carer reports of children and young people who have ever been treated for an emotional or mental health problem.

|

6 to 10 years |

11 to 15 years |

|

|

2009-10 |

5.1 |

10.6 |

|

2011-12 |

6.5 |

9.7 |

|

2013-14 |

5.3 |

14.0 |

|

2015-16 |

9.9 |

12.2 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009-2016 [unpublished]

In the combined calendar years of 2015 and 2016, WA parents and carers reported that approximately 9.9 per cent of children aged six to 10 years and 12.2 per cent of children aged 11 to 15 years had been treated for an emotional or mental health problem in their lifetime.

Parents and carers reported that approximately one in 10 girls and one in eight boys aged six to 15 years were treated for an emotional or mental health problem.

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

2009-10 |

9.1 |

6.7 |

8.0 |

|

2011-12 |

9.4 |

6.8 |

8.1 |

|

2013-14 |

13.0 |

6.9 |

9.9 |

|

2015-16 |

12.5 |

9.7 |

11.1 |

Source: Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA from the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009-2016 [unpublished]

Parents and carers were also asked whether they thought their child needed special help for an emotional, concentration or behavioural problem.

|

5 to 9 years |

10 to 15 years |

|

|

2012 |

31.5 |

29.5 |

|

2013 |

31.8 |

36.2 |

|

2014 |

32.7 |

43.7 |

|

2015 |

24.8* |

44.8 |

|

2016 |

39.2 |

37.4 |

|

2017 |

46.5 |

28.1 |

|

2018 |

33.7 |

55.0 |

Source: Patterson C et al, Health and Wellbeing of Children in Western Australia in 2018, Overview and Trends (and previous years’ reports)22

* Prevalence estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

In 2018, the proportion of young people aged 10 to 15 years whose parents and carers felt they needed special help was 55.0 per cent. The high proportions across age groups will be in part because the term ‘special help’ is very broad and incorporates concentration and behavioural issues.

The results for children and young people aged 10 to 15 years are generally higher than the Young Minds Matter survey where just over a quarter (26.8%) of all Australian parents and carers reported that in the previous 12 months their child or adolescent had some need for help for emotional or behavioural problems. In this survey (conducted in 2007) the most common type of help identified was counselling or talking therapy.23

The Young Minds Matter survey highlights the difficulty of relying on parent-reported data rather than diagnostic assessment. This survey identified children meeting the DSM-IV criteria for mental disorders, including clinically significant impairment of functioning, yet 21 per cent of parents of these children did not identify any need for help for their child.24 However, the researchers noted this was particularly significant for the children aged four to 11 years.25

The Young Minds Matter survey also found that children in low-income families, with parents and carers with lower levels of education and with higher levels of unemployment had higher rates of mental disorders.26 Other Australian research has determined that in the most disadvantaged quintile, the percentage (24.4%) of adults with mental disorders was 50 per cent higher than that in the least disadvantaged quintile (16.9%).27

The Young Minds Matter survey also reported a higher rate of mental disorders in non-metropolitan areas.28

Research conducted by ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia with young people aged 15 years and over living in regional and remote Australia found that challenges associated with living in regional or remote areas included feelings of loneliness, isolation, boredom and aimlessness due to a lack of social, recreational and/or employment opportunities.29

Children and young people with parents who have a mental illness also have a higher likelihood of experiencing mental health issues.30 A study in 2008 concluded that approximately 23.3 per cent of Australian children had a parent with a non-substance related mental illness.31 This can affect children in multiple ways, including experiencing a chaotic home environment, higher levels of stress and homelessness, which are all risk factors for mental health issues for the child. Protective factors, such as a supportive other parent, can buffer the effect of one parent’s mental health issues.32

Aboriginal children and young people are more likely to have mental health problems than non-Aboriginal children and young people.33 The legacy of colonisation has affected multiple generations of Aboriginal peoples.34,35 The nature of unresolved trauma and the intergenerational effects in Aboriginal communities extends ‘to all dimensions of the holistic notion of Aboriginal wellbeing, including psychological, social, spiritual and cultural aspects of life and connection to land’.36 Children and young people exposed to significant disadvantage and trauma experience far greater risk factors to their mental health – thus compounding the cycle of disadvantage.

The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey conducted in 2000 and 2001 reported that almost one quarter (24.0%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 17 years were at high risk of clinically significant emotional or behavioural difficulties. This was significantly higher than the 15 per cent for WA’s general child population.37

No recent data exists on the mental health issues experienced by Aboriginal children and young people in WA.38,39

The Young Minds Matter survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use for Aboriginal peoples due to the random sampling methodology and cultural issues that could not be addressed sufficiently in a national survey.40

Aboriginal adults across Australia are:

- 1.3 times more likely to have mental health problems managed by their general practitioner

- twice as likely to be hospitalised for mental health conditions, and

- almost twice as likely to die by suicide as non-Aboriginal Australians.41

Research strongly suggests that around half of mental health issues in adulthood develop by the mid-teens,42 therefore investment into the prevention and early intervention of mental health issues of Aboriginal children and young people should be a high priority for government.

For further information on the mental health of Aboriginal children and young people refer to the Commissioner’s 2012 policy brief: The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people.

Children and young people in the youth justice system

Children and young people in the youth justice system are also more likely to have mental health issues.43 The Banksia Hill Detention Centre is the only facility in WA for the detention of children and young people 10 to 17 years of age who have been remanded or sentenced to custody. During 2017-18, approximately 148 children and young people aged between 10 and 17 years were held in the Banksia Hill Detention Centre in WA on an average day.44

In 2017, a Telethon Kids Institute research team found that 89 per cent of young people in WA’s Banksia Hill Detention Centre had at least one form of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, while 36 per cent (36 young people) were found to have Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). While FASD is not a mental illness, it is a cognitive disability which has a significant impact on mental health and increases the likelihood of social and emotional behavioural issues that are often not diagnosed.45,46

It is of significant concern that only two of the young people with FASD had been diagnosed prior to participation in the study.47 This highlights a critical need for improved health assessment and diagnosis processes in the juvenile justice system and other services systems more broadly.

Children and young people entering youth detention have the right to be assessed to determine whether they have a physical or intellectual disability, mental health issues, learning difficulties or experience other forms of vulnerability and to have those needs met.

No other data exists on the prevalence of mental health issues for children and young people in the youth justice system in WA.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex children

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI)48 children and young people are also at an increased risk of a range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, self-harm and suicide.49

The issues that affect LGBTI people largely stem from social and cultural beliefs and assumptions about gender and sexuality. As a result of these beliefs and social norms they have a much higher likelihood of experiencing abuse, violence and systemic discrimination at an individual, social, political and legal level than non-LGBTI people.50

Administrative data on the prevalence of self-harm behaviour for children and young people who identify as LGBTI are not available, as unlike other demographic characteristics, LGBTI status or identity is not captured in most data collections.51

Survey data has found that almost one-quarter of same-sex attracted Australians experienced a major depressive episode in 2005 and have up to 14 times higher rates of suicide attempts than their heterosexual peers.52 Furthermore, a study into the mental health of trans young people found that almost three-quarters (74.6%) of participating trans young people (aged 25 years or under) have at some point been diagnosed with depression and 72.2 per cent have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.53

There is no available data on the experience of mental health issues by WA young people who identify as LGBTI.

For more information on LGBTI children and young people, refer to the Commissioner’s 2018 issues paper: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) children and young people.

Culturally and linguistically diverse children

There is limited data on the prevalence of mental health issues for young people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds.

Data from the 2016 Census of Population and Housing shows that 17.3 per cent of 0 to 17 year-olds in WA were born in a country other than Australia and New Zealand (Oceania). The most common region of birth after Australia and New Zealand is North-West Europe (3.6%), followed by South-East Asia (2.7%) and Sub-Saharan African (1.8%).54

In WA, 17.5 per cent of people spoke a language other than English at home in 2016. Other than English, Mandarin was the most common, with 1.9 per cent of people speaking this language at home. The next most common languages were Italian, Filipino/Tagalog and Vietnamese.55

There is some evidence to suggest that children and young people from refugee and some migrant backgrounds are more likely to experience mental health problems than the general population.56 This is often as a result of significant disadvantage and trauma related to their refugee, migration and settlement experience.57,58

Some children and young people from CALD backgrounds (and their families) experience language barriers, feeling torn between cultures, intergenerational conflict, racism and discrimination, bullying and resettlement stress.59 Some of these children and young people have traumatic pre-migration experiences, including family separation, war, violence and immigration detention, which can also impact their mental health and wellbeing.

Yet, research suggests that people from CALD backgrounds often do not seek help for mental health issues. This can be for cultural reasons, because information is not available in community languages, or there is no culturally appropriate service available.60

There is no data available on the mental health of young people in WA of a CALD background.

For more information refer to the Commissioner’s policy brief:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2013, The mental health and wellbeing of children and young people: Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Endnotes

- Kim-Cohen J et al 2003, Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective longitudinal cohort, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 60, No 7.

- The Commissioner recognises that Aboriginal people have a holistic view of mental health – a view that incorporates the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of individuals and their communities and the importance of connection to the land, culture, spirituality, ancestry, family and community. For more information refer to Dudgeon P et al (eds) 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice – Second edition, Australian Government.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2012, Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

- Mission Australia and Black Dog Institute 2017, Youth mental health report: Youth Survey 2012-2016, Mission Australia.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) 2018, Adolescent Mental Health Fact Sheet, WHO.

- McGorry P et al 2014, Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform, The Lancet Psychiatry, Vol 1.

- Mental Health Australia 2014, Getting the NDIS right for people with psychosocial disability, Mental Health Council of Australia.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government.

- Garten A et al 1998, The Western Australian Child Health Survey: A review of what was found and what was learned, The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, Vol 15 No 1.

- Zubrick S et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 146.

- The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV) is a validated tool for identifying mental disorders in children and adolescents according to criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders Version IV (DSM-IV). Source: Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australia Government, p. 23.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 18.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government.

- Quinn P 2015, Treating adolescent girls and women with ADHD: Gender-specific issues, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol 61, No 5.

- Walters A 2018, Girls with ADHD: Underdiagnosed and untreated, The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, Vol 34, No 11.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 99.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 99.

- The WA Department of Health’s, Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System is a continuous data collection which was initiated in 2002 to monitor the health status of the general population. In 2017, 780 parents/carers of children aged 0 to 15 years were randomly sampled and completed a computer assisted telephone interview between January and December, reflecting an average participation rate of just over 90 per cent. The sample was then weighted to reflect the Western Australian child population.

- Custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the WA Department of Health Epidemiology Branch, Selected risk factor estimates for WA children using the WA Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System, 2009-2016 [unpublished]. Results from WA Children’s Health and Wellbeing Survey where parents were asked whether a doctor had ever told them that their child has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

- This data has been sourced from individual annual Health and Wellbeing Surveillance System reports and therefore has not been adjusted for changes in the age and sex structure of the population across these years nor any change in the way the question was asked. No modelling or analysis has been carried out to determine if there is a trend component to the data, therefore any observations made are only descriptive and are not statistical inferences.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 81.

- Johnson S et al 2018, Mental disorders in Australian 4- to 17- year olds: Parent-reported need for help, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 52, No 2.

- Ibid.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 26.

- Enticott J et al 2016, Mental disorders and distress: Associations with demographics, remoteness and socioeconomic deprivation of area of residence across Australia, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 50 No 12.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 26.

- Ivancic L et al 2018, Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia, ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia.

- Mowbray C et al 2006, Psychosocial outcomes for adult children of parents with severe mental illnesses: demographic and clinical history predictors, Health and Social Work, Vol 31.

- Maybery D et al 2009, Prevalence of parental mental illness in Australian families, Psychiatric Bulletin, Vol 33.

- Reupert D et al 2013, Children whose parents have a mental illness: prevalence, need and treatment, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 199, No 3 supplement.

- Zubrick SR et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 1997, Bringing them home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, Australian Government.

- Atkinson J 2013, Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children: Resource sheet no 21 produced for Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Zubrick SR et al 2014, Chapter 6: Social Determinants of Social and Emotional Wellbeing, in Dudgeon P et al 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network, p. 99.

- Zubrick SR et al 2005, The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: The Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children and Young People, Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, p. 25.

- The Young Minds Matter survey could not produce estimates of mental disorders and service use for Aboriginal peoples due to the random sampling methodology and cultural issues that could not be addressed sufficiently in a national survey (p. 146). Similarly, the ReachOut and Mission Australia survey of young people’s mental health in regional and remote areas were unable to recruit sufficient numbers of young people who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander to be able to examine the experiences and needs of this group separately (p. 11).

- Ivancic L et al 2018, Lifting the weight: Understanding young people’s mental health and service needs in regional and remote Australia, ReachOut Australia and Mission Australia, p. 11.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 146.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015, The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2015, Cat No IHW 147, AIHW, p. 80.

- Kessler RC et al 2005, Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication, Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol 62, p 1.

- Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network and Juvenile Justice NSW 2015, 2015 Young People in Custody Health Survey: Full Report, NSW Government, p. 65.

- WA Department of Justice 2018, Annual Report: 2017-18, WA Government, p. 15.

- Brown J et al 2018, Fetal Alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): A beginner’s guide for mental health professionals, Journal of Neurological Clinical Neuroscience, Vol 2, No 1.

- Pei J et al 2011, Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Journal Of Mental Health, Vol 20, No 5.

- Bower C et al 2018, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

- The Commissioner for Children and Young People understands there are a range of terms and definitions that people use to define their gender or sexuality. The Commissioner’s office will use the broad term LGBTI to inclusively refer to all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex, as well as to represent other members of the community that use different terms to describe their diverse sexuality and/or gender.

- Leonard W et al 2012, Private Lives 2: The second national survey of the health and wellbeing of gay,lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) Australians, Monograph Series Number 86, The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health & Society, La Trobe University.

- Rosenstreich G 2013, LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide, Revised 2nd Edition, National LGBTI Health Alliance, p. 4.

- Ombudsman Western Australia 2014, Investigation into ways that State government departments and authorities can prevent or reduce suicide by young people, WA Government, p. 35.

- Rosenstreich G 2013, LGBTI People Mental Health and Suicide, Revised 2nd Edition, National LGBTI Health Alliance, p. 3.

- Strauss P 2017, Trans Pathways: the mental health experiences and care pathways of trans young people, Telethon Kids Institute, p. 10.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, Census of Population and Housing, 2016, TableBuilder – Dataset 2016 Census – Cultural Diversity, ABS.

- .id the population experts, Western Australia Community Profile – Language Spoken at Home [website], sourced from the ABS 2016 Census.

- De Anstiss H and Ziaian T 2010, Mental health help-seeking and refugee adolescents: Qualitative findings from a mixed-methods investigation, Australian Psychologist, Vol 45, No 1.

- Fazel M and Stein R 2002, The mental health of refugee children, Archives of disease in childhood, Vol 87.

- Francis S and Cornfoot S 2007, Multicultural youth in Australia: Settlement and transition, Centre for Multicultural Youth Issues for the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth,

- WA Office of Multicultural Interests 2009, Not drowning, waving: Culturally and linguistically diverse young people at risk in Western Australia, WA Government, p. 5.

- Australian Department of Health, Fact Sheet 20: Suicide prevention and people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, Australian Government.

Last updated September 2019

Providing services for mental health issues early in a young person’s life not only reduces individual suffering, but can also produce long-term cost savings to the government and the community.1,2

Yet, the Commissioner’s 2011 Inquiry into the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people in Western Australia and the follow up “Our Children Can’t Wait” report found there has been significant underfunding of mental health services for WA children and young people relative to the funding received by adult mental health services, as well as relative to need.

Many young people with mental health issues will not access mental health services. This is for a number of reasons including stigma around seeking help, concerns about confidentiality, limited availability of affordable and age-appropriate services particularly in regional and remote locations and a low level of parental and community awareness regarding the importance of supporting young people’s mental health by accessing appropriate services.3

Therefore, the administrative data in this measure will underrepresent the extent of mental health problems experienced by young people in the community. However, it does provide some information on service use by WA young people.

Administrative data from the WA Department of Health’s Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provides data on hospital separations4 for children and young people with mental health issues. It also provides information on the number of children and young people who received services from public child and adolescent community mental health services.

|

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

|

2012 |

1,171 |

148.1 |

|

2013 |

1,124 |

142.7 |

|

2014 |

933 |

118.7 |

|

2015 |

891 |

114.0 |

|

2016 |

879 |

111.7 |

|

2017 |

1,023 |

n/a |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

n/a - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health or discharged from a designated psychiatric ward.

2. Age Group is based on patient's age at the time of admission into hospital

3. Figures are subject to change.

4. Age-specific rate is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

In 2017, 1,023 WA young people aged 13 to 17 years separated from a WA public or private hospital with a principal diagnosis of a mental health condition. The top three principal diagnoses were borderline personality disorder, severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms and anorexia nervosa.5

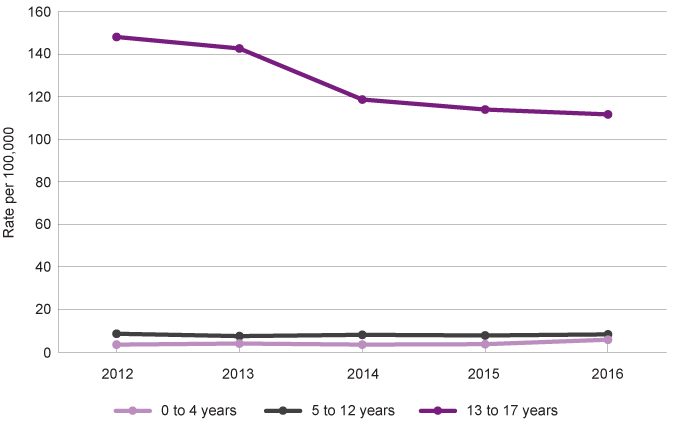

From 2012 to 2016 there was a reduction in the age-specific rate of separations from hospital with a mental health diagnosis for WA young people aged 13 to 17 years. The rate for 2017 is not yet available.

The table below highlights the increase in service-use as children age, in particular as they enter adolescence.

|

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

|

2012 |

3.5 |

8.6 |

148.1 |

|

2013 |

4.0 |

7.5 |

142.7 |

|

2014 |

3.5 |

8.1 |

118.7 |

|

2015 |

3.7 |

7.8 |

114.0 |

|

2016 |

5.8 |

8.3 |

111.7 |

|

Total |

4.1 |

8.1 |

127.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-code) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rates of mental-health related separations from public or private hospitals among children and young people by selected age groups, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Rates of mental health hospital separations continue to increase until middle age, with the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reporting that the rate for overnight admitted mental health separations with specialised care is 55 per 100,000 for Australian young people under 15 years of age and 940 per 100,000 for young people aged 15 to 24 years. In comparison, Australian adults aged 35 to 44 years have the highest rate of overnight admitted mental health separations with specialised care at 1,082 per 100,000 people.6

Young people aged 13 to 17 years separating from a WA hospital are most likely to be diagnosed with a personality disorder or depression and anorexia is the third most common disorder.7

The reduction in mental health hospital separations from 2013 to 2016 could be due to a variety of reasons including better targeted mental health services reducing the need for hospital admittance or a reduction in accessibility of hospital beds and services.

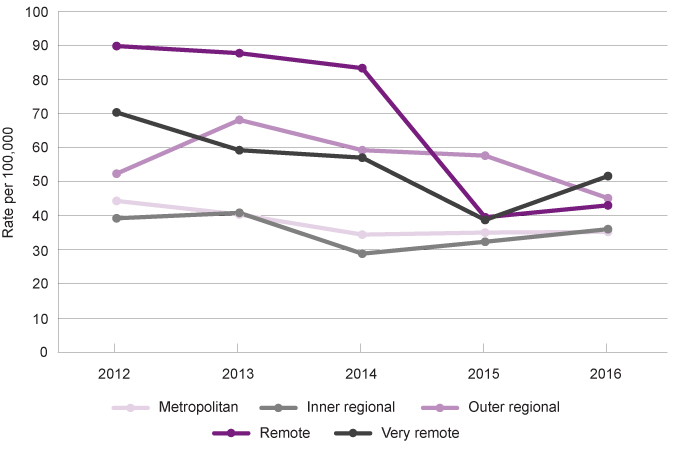

Young people living in regional and remote areas are more likely to be discharged from a hospital with a mental health diagnosis than young people living in the metropolitan area.

|

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total* |

|

|

2012 |

832 |

319 |

1,171 |

|

2013 |

761 |

348 |

1,124 |

|

2014 |

623 |

299 |

933 |

|

2015 |

637 |

249 |

891 |

|

2016 |

628 |

240 |

879 |

|

2017 |

757 |

253 |

1,023 |

|

Total (2012-2017) |

4,238 |

1,708 |

6,021 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

* Totals do not sum as total includes where patient’s residential address was unknown, no fixed permanent address or residence outside Australia.

Note: Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-code) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

Age-specific rates for this age group by region are not available, however for children and young people aged 0 to 17 years the rate of separations from hospital with a mental health diagnosis is significantly higher in outer regional and remote areas than in the metropolitan area and inner regional.

|

Metropolitan |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

|

|

2012 |

44.4 |

39.3 |

52.4 |

89.9 |

70.4 |

|

2013 |

40.4 |

40.9 |

68.2 |

87.8 |

59.3 |

|

2014 |

34.5 |

28.9 |

59.3 |

83.4 |

57.1 |

|

2015 |

35.1 |

32.4 |

57.7 |

39.6 |

38.8 |

|

2016 |

35.3 |

36.1 |

45.2 |

43.1 |

51.7 |

|

Total |

38.0 |

35.5 |

56.6 |

68.7 |

55.4 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health or discharged from a designated psychiatric ward.

2. Age-adjusted rate per 100,000 population. Direct standardisation using all age groups of 2001 Australian Standard Population in order to compare rates between population groups and different years for the same population group.

Rates of mental-health related separations from public or private hospitals among children and young people aged 0 to 17 years by year and remoteness area, age-adjusted rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

There has been a substantial reduction in the rate of mental-health related separations in remote and very remote regions from 2012 to 2016. This will continue to be monitored to determine if this is an ongoing trend.

There are multiple factors that can result in a lower rate of children and young people being discharged from hospital with a mental health diagnosis. This can include initiatives to address mental health issues earlier through community-based services, avoiding the need for a hospital stay. However, a reduction in the rate of separations, does not necessarily mean a reduction in need – it could also be a reduction in service availability.

For example, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report on hospital resources shows that the average available number of public hospital beds per 1,000 population in WA was 2.31 in 2017-18.8 This was the lowest number of beds per 1,000 population of all states and territories (excluding the Northern Territory which did not provide the number of beds for all hospitals).

It should be noted that the Perth Children’s Hospital opened in 2018 with a mental health inpatient unit comprising a 14-bed acute section for children and adolescents who require a high level of assessment, monitoring and treatment and six beds for those who require less support and supervision during their treatment and recovery.9

|

Male |

Female |

|||

|

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

|

2012 |

365 |

91.5 |

785 |

196.8 |

|

2013 |

338 |

84.7 |

770 |

193.0 |

|

2014 |

261 |

65.4 |

660 |

165.4 |

|

2015 |

274 |

68.7 |

605 |

151.6 |

|

2016 |

248 |

62.2 |

611 |

153.2 |

|

2017 |

307 |

n/a |

697 |

n/a |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Hospital Morbidity Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

n/a - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

* The Hospital Morbidity Data Collection does not capture data on gender but biological sex (male/female).

Notes:

1. Figures only include patients who were diagnosed with ICD-10-AM Primary Diagnosis Code of Mental Health (F-code) or discharged from a designated psychiatric hospital/ward.

2. Age-specific rate (ASPR) is the number of separations for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Female young people aged 13 to 17 years in WA are significantly more likely to separate from a hospital for mental health issues than male young people of the same age group. WA male and female children under 13 years of age have similar rates of separation from a hospital with a mental health diagnosis (refer to the Mental Health Indicator for 6 to 11 years), therefore this represents a significant shift for female young people in adolescence.

This aligns with the data from the Mission Australia survey which highlights that WA female young people (aged 15 to 19 years) are more likely to be concerned about issues such as coping with stress and mental health, and are less likely to describe themselves as happy or positive about the future (refer to Measure: Positive outlook on life).

The WA Department of Health also collects data on the number of WA children and young people who receive services from public child and adolescent community mental health services.

This data only includes public mental health service provision, including outpatient and community mental health services. The public mental health system typically provides services to people with moderate to severe mental health issues, whereas people with mild or emerging mental health issues are often supported by community organisations, support services or primary health providers, for example, general practitioners, counsellors, private practitioners or services such as headspace.

|

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

|

2012 |

4,260 |

599.1 |

|

2013 |

4,992 |

686.5 |

|

2014 |

5,069 |

670.9 |

|

2015 |

4,796 |

620.3 |

|

2016 |

5,145 |

648.7 |

|

2017 |

5,711 |

n/a |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

n/a - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

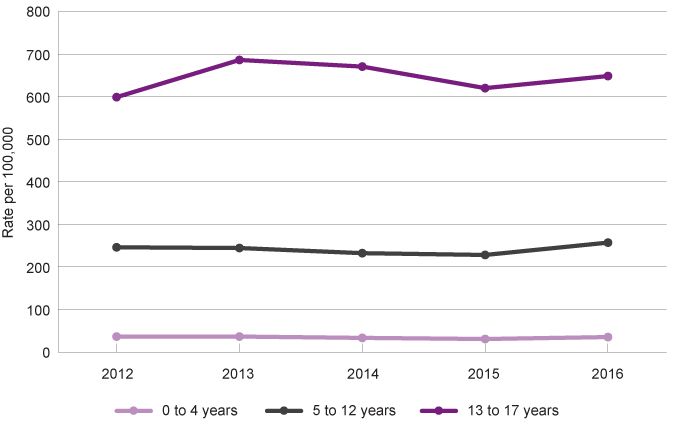

In 2016, the age-specific rate service contacts for young people aged 13 to 17 years increased from the previous year (648.7 per 100,000 in 2016 compared to 620.3 per 100,000 in 2015).

|

0 to 4 years |

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|

|

2012 |

36.4 |

246.2 |

599.1 |

|

2013 |

36.4 |

244.5 |

686.5 |

|

2014 |

33.3 |

232.4 |

670.9 |

|

2015 |

30.7 |

228.2 |

620.3 |

|

2016 |

35.2 |

257.2 |

648.7 |

|

Total |

34.4 |

241.7 |

645.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rate of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people by selected age groups, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Data Collection provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

The age-specific rate of service contacts at public mental health community services for children aged five to 12 years (257.2 per 100,000 in 2016) is significantly lower than the age-specific rate of public mental health community service contacts for children aged 13 to 17 years (648.7 per 100,000 in 2016). This highlights an increase in service-use as children age, in particular as they enter adolescence.

This increase could be related to higher need or severity of mental health issues as children get older and enter adolescence, particularly if their mental health issues have not been identified and addressed at an earlier stage. This could also be influenced by the lack of community awareness and identification of mental health issues in young children and also public service availability for that younger age group.

The age-specific rate of mental-health related service contacts for young people aged 13 to 17 years in WA has fluctuated from 2012 to 2016 with no clear trend.

|

Male |

Female |

|||

|

Number |

Age-specific rate |

Number |

Age-specific rate |

|

|

2012 |

1,878 |

470.7 |

2,739 |

686.6 |

|

2013 |

2,052 |

514.4 |

3,272 |

820.2 |

|

2014 |

2,111 |

529.1 |

3,282 |

822.7 |

|

2015 |

2,012 |

504.3 |

3,083 |

772.8 |

|

2016 |

2,133 |

534.7 |

3,327 |

833.9 |

|

2017 |

2,350 |

n/a |

3,715 |

n/a |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

n/a - rate is not available for 2017 at time of publication.

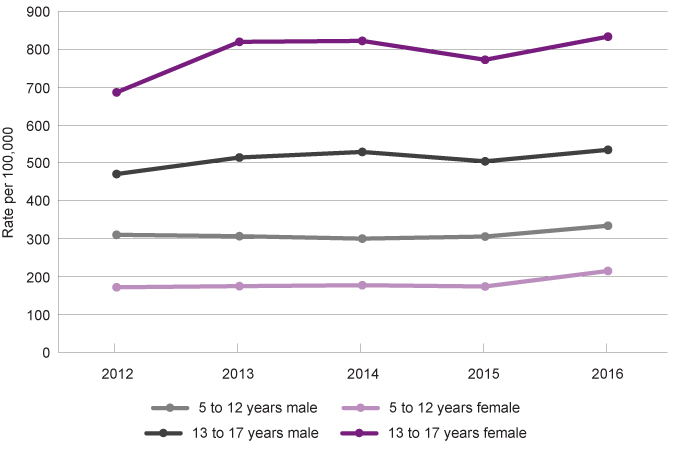

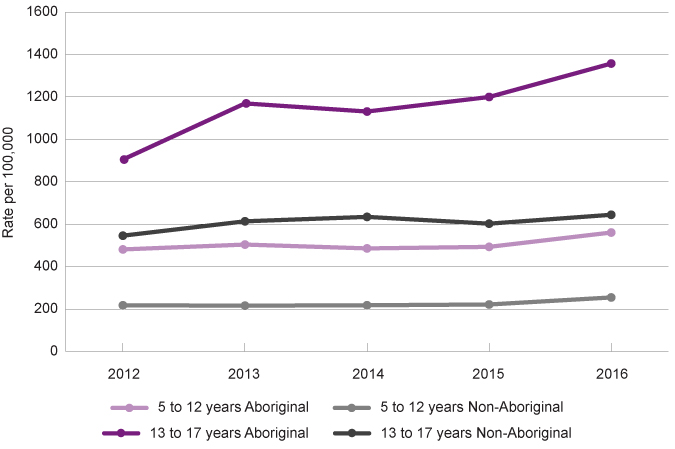

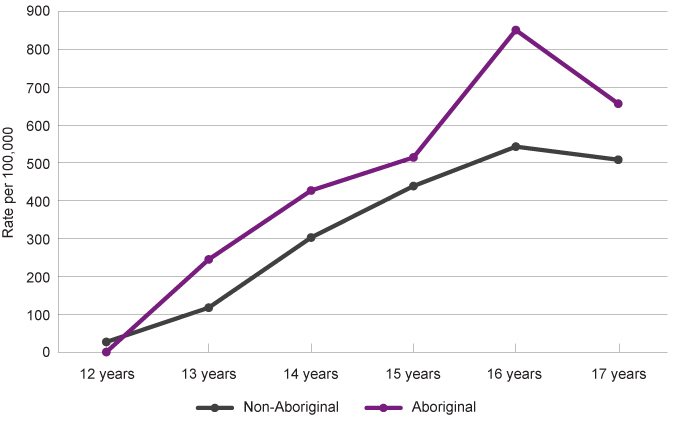

Over the five years from 2012 to 2016, female young people aged 13 to 17 years had a much higher age-specific rate of contact with public mental health services (833.9 per 100,000 in 2016) than male young people aged 13 to 17 years (534.7 per 100,000 in 2016).

This represents a substantial shift from the younger age group where male children aged five to 12 years had higher rates of service than female children (311.1 compared to 189.3 from 2012 to 2016, respectively).

|

5 to 12 years |

13 to 17 years |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

2012 |

310.0 |

171.3 |

470.7 |

686.6 |

|

2013 |

306.3 |

174.3 |

514.4 |

820.2 |

|

2014 |

299.9 |

176.7 |

529.1 |

822.7 |

|

2015 |

305.4 |

173.4 |

504.3 |

772.8 |

|

2016 |

334.0 |

214.4 |

534.7 |

833.9 |

|

Total |

311.1 |

189.3 |

510.6 |

830.8 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-specific rate is the number of service contacts for an age group divided by the population for the age group, expressed as per 100,000 population.

Rate of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people by selected age groups and sex, age-specific rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Research suggests that there are multiple factors influencing the differences between male and female children and young people experiencing mental health issues and receiving mental health services, including:

- Male children and young people are more likely to display ‘externalising’ behaviours and problems with attention, self-regulation or antisocial behaviour, while female children and young people are ‘prone to symptoms that are directed inwardly’ or internalising behaviours, including depression, withdrawal, feelings of inferiority or shyness.10 These internalising behaviours may be less noticeable or recognisable than externalising behaviours, and therefore may not result in referral for services.

- Male young people are less likely to seek help, often due to social pressure, stigma,11 wanting to keep their problems to themselves, or feeling that they don’t have anyone to talk to.12

- Female young people are more likely to experience anxiety and depression due to social norms regarding gender roles (including body-image) and also a higher likelihood of experiencing gender-based violence and abuse.13

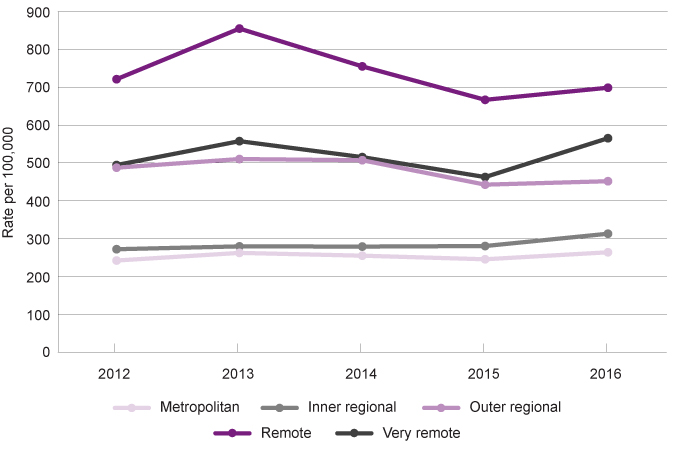

Children and young people in remote, very remote and outer regional areas have a consistently higher rate of accessing public mental health services than children and young people in the inner regional and metropolitan areas.

|

Metropolitan |

Inner regional |

Outer regional |

Remote |

Very remote |

|

|

2012 |

242.0 |

271.9 |

487.5 |

721.4 |

494.5 |

|

2013 |

262.2 |

279.4 |

510.3 |

855.3 |

557.6 |

|

2014 |

254.8 |

278.9 |

507.2 |

755.3 |

515.4 |

|

2015 |

245.3 |

280.3 |

442.6 |

666.9 |

462.7 |

|

2016 |

263.8 |

312.9 |

451.7 |

698.9 |

565.4 |

|

Total |

253.6 |

284.7 |

479.9 |

739.6 |

519.1 |

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Note: Age-adjusted rate per 100,000 population. Direct standardisation using all age groups of 2001 Australian Standard Population in order to compare rates between population groups and different years for the same population group.

Rates of service contacts at public child and adolescent community mental health services among children and young people aged 0 to 17 years by year and remoteness area, age-adjusted rate, WA, 2012 to 2016

Source: Custom report from the WA Department of Health, Mental Health Information System provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

From 2013 to 2015 there was a reduction in the age-adjusted rate of children and young people accessing public mental health services in the outer regional and remote areas of WA. In 2016, the age-adjusted rate increased across all areas of WA.

Data of this nature should be considered with caution. A measure of mental health service use is not a measure of prevalence of mental health issues in a population. In particular, one young person may have had multiple service contacts. Furthermore, the reasons for changes in the rate of accessing mental health services can be varied. It could be due to a lower proportion of children and young people experiencing mental health problems and a commensurate decrease in the number of services. Alternatively, a reduction in the rate of service could be related to issues with accessibility of the services, such that children and young people have a mental health issue but are unable to access an appropriate service in their area.