Connection to community, culture and support

Connection to culture and community is critical for young people’s health and wellbeing. It provides a positive sense of identity and belonging.

It is also important that young people have supportive relationships and feel confident to ask for help if they have any emotional worries or health concerns.

Last updated August 2021

Some data is available on WA young people’s connection to culture, community and support.

Overview

This indicator considers WA young people’s connection to culture and community and whether they know how to get help if they have any emotional and health concerns.

Young people benefit from a connection to culture and community as it provides them with a positive sense of identity and encourages supportive relationships.1 Young people also need relationships with adults that are stable, caring and supportive enabling them to ask for help if they have any worries or concerns.

In the Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey, more than one-half (56.6%) of Year 7 to Year 12 WA students report that they feel like they belong in their community.

Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly more likely than non-Aboriginal students to feel like they belong in their community (65.4% compared to 56.1%).

Areas of concern

Female students were significantly more likely than male students to report that in the last 12 months there was a time when they wanted to see someone for their health, but were unable to (35.0% compared to 17.7%).

Endnotes:

Last updated August 2021

Feeling connected to community and culture is critical for young people aged 12 to 17 years as it encourages a sense of belonging, a positive sense of identity and the development of respectful and responsive relationships.1,2

A sense of belonging and connectedness can be strengthened in multiple ways including, participation in cultural or community-based activities, spending time with grandparents, learning about family history, finding like-minded young people on social media, having good access to services and enjoying positive relationships with neighbours. Through these diverse experiences young people develop a positive sense of self and identity. It can also provide young people with additional support and role models within, and outside, of the family.3

Connection to culture and community is also related to young people’s participation in their own lives and in the broader community. It increases young people’s understanding of their rights and responsibilities and strengthens their interest and skills in becoming active contributors to their world.4

Young people should have their voices heard and be actively involved in decisions affecting their lives. Refer to the Autonomy and voice Indicator for more information on young people’s active sense of participation in their lives and their communities.

Connection to culture and community can take many forms including participation in sporting clubs, cultural events, religious organisations and community groups (e.g. scouts). It can also include relationships with neighbours and accessibility of local community spaces.

Having a connection and sense of belonging in a community can be more difficult for some young people. In particular, young people with disability, culturally and linguistically diverse young people, Aboriginal young people and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or intersex (LGBTI) young people can experience discrimination and bullying that limits their ability to feel connected and supported within their broader community.5,6,7

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions on culture and community.8

In this survey, three-quarters (74.4%) of students in Year 7 to Year 12 reported being born in Australia, the next most common country of birth was England (4.9%), New Zealand (3.1%) and the Philippines (2.7%).9

Students were asked what cultural background they have; they were able to select multiple responses. Two-thirds (67.1%) of students in Year 7 to Year 12 reported having an Australian cultural background and 6.4 per cent reported having an Aboriginal Australian background.10

Having an English cultural background (35.1%) was the most common background besides Australian. Smaller proportions of students reported having Scottish (15.5%), Irish (13.0%), Italian (9.1%), Chinese (4.8%) and Indian (4.6%) backgrounds.11

Most students (92.6%) in Year 7 to Year 12 reported speaking English at home, the next most common languages spoken at home were Filipino/Tagalong (2.3%) and Cantonese/Mandarin (1.6%).12

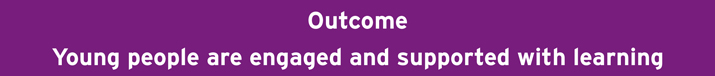

In SOS19, students were asked whether they felt like they belonged in their community. Overall, more than one-half (56.6%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they agree a lot (27.8%) or a bit (28.8%) that they feel like they belong in their community.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Disagree a lot |

4.9 |

7.3 |

5.6 |

8.6 |

6.9 |

6.1 |

|

Disagree a bit |

8.3 |

11.1 |

9.7 |

12.0 |

6.7 |

9.9 |

|

Neither agree or disagree |

25.0 |

30.3 |

29.2 |

21.3 |

16.5 |

27.4 |

|

Agree a bit |

30.3 |

27.4 |

28.6 |

30.2 |

28.7 |

28.8 |

|

Agree a lot |

31.5 |

23.9 |

26.9 |

28.0 |

41.2 |

27.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who feel like they belong in their community by various characteristics, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly less likely than male students to agree a lot that they feel like they belong in their community (female students 23.9% compared to 31.5% male students). Only one-half (51.3%) of female high school students agreed that they feel like they belong in their community (compared to 61.8% of male students).

Young people in remote areas were significantly more likely than students in metropolitan and regional areas to agree a lot that they feel like they belong in their community (remote: 41.2%, regional: 28.0%, metropolitan: 26.9%).

Young people in regional locations were more likely than those in metropolitan or remote areas to disagree (a lot or a bit) that they feel like they belong in their community (regional: 20.6%, metropolitan: 15.3%, remote: 13.6%).

Students in regional locations were also significantly less likely than students in metropolitan areas to agree a lot that there are outdoor places to go in their local area (52.0% compared to 63.4%). They were also significantly more likely than metropolitan students to agree a lot that there is nothing to do in their local area (22.7% compared to 11.3%).13

Over one-third (38.3%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students agree a lot that their neighbours are friendly, while one quarter (26.0%) agree a bit that their neighbours are friendly. A significant proportion (22.5%) neither agree nor disagree that their neighbours are friendly, while 13.3 per cent disagree (a bit: 6.9%, a lot: 6.4%).14

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were less likely than male students to agree a lot or a bit that their neighbours are friendly (62.4% compared to 66.9%). This is a shift from primary school, where a higher proportion of female students than male students in Year 4 to Year 6 agreed their neighbours were friendly (76.9% compared to 72.6%).15

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were also significantly less likely than male students to feel safe in their local area or to be allowed to go out alone at night. For more information refer to the Safe in the community indicator.

Similar responses were reported regarding neighbours by young people across geographical regions and by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people.16

Students in SOS19 were also asked how often they usually spend time practising or playing a sport (like footy training, gymnastics, swimming) outside of school. While, this is not a direct measure of connection to community, being involved in community-based sport or other physical activities have been shown to improve people’s sense of community connectedness.17

Overall, one-quarter (25.4%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students said they hardly ever or never spend time practising or playing a sport outside of school and nine per cent did sport less than once a week. Less than one-third (30.9%) said they spend time practising or playing a sport every day or almost every day outside of school, while a similar proportion (31.3%) said they do this once or twice a week.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

Every day or almost every day |

35.7 |

26.0 |

30.7 |

28.6 |

39.9 |

30.9 |

|

Once or twice a week |

31.8 |

30.9 |

30.5 |

35.3 |

33.1 |

31.3 |

|

Less than once a week |

7.1 |

11.1 |

9.3 |

8.8 |

3.5 |

9.0 |

|

Hardly ever or never |

22.1 |

28.6 |

26.1 |

23.3 |

19.5 |

25.4 |

|

I don't know |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

4.0 |

4.1 |

3.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Young people in remote locations were more likely to play or practise a sport outside of school every day or almost every day than young people in the metropolitan or regional areas (39.9% compared to 30.7% and 28.6%).

Female students were less likely than male students to play or practise a sport every or almost every day outside of school (26.0% compared to 35.7%) and more likely to hardly ever or never play or practise a sport outside of school (28.6% compared to 22.1%).

Further analysis of the SOS19 results show that there is a statistically significant relationship between playing sport and belonging, such that students who play sport regularly are more likely to feel like they belong in their community (and vice versa).18

In 2020, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the results of the 2019 General Social Survey. This survey provides information on Australians aged between 15 and 64 years. There is no data on children and young people younger than 15 years.

In this survey, 28.8 per cent of Australian 15 to 24-year-olds had undertaken unpaid voluntary work through an organisation in the past 12 months, 36.5 per cent had undertaken informal volunteering, while 90.6 per cent had family or friends living outside the household to confide in.19

In 2017–18, the ABS collected data on children and young people’s participation in selected creative activities including drama, singing, dancing and art and craft outside of school hours. These activities could be at home or at community venues.

While, this data does not directly measure a sense of connection, it does provide some information on WA children and young people’s engagement in community and culture.

|

5 to 8 years |

9 to 11 years |

12 to 14 years |

|

|

Drama activities |

6.1 |

10.2 |

7.7 |

|

Singing or playing a musical instrument |

19.5 |

26.9 |

24.3 |

|

Dancing |

20.8 |

15.8 |

11.4 |

|

Art and craft activities |

47.8 |

37.9 |

26.5 |

|

Creative writing |

25.2 |

24.2 |

16.2 |

|

Creating digital content |

10.5 |

20.8 |

20.3 |

|

Total creative activities |

66.6 |

65.2 |

56.6 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, Participation in Selected Cultural Activities, Table 12: Children aged 5-14 years, Type of activity by age

This data suggests children’s participation in dancing, art and craft and creative writing activities decreases as they age.

Participation in musical activities remains high from nine to 14 years of age (5 to 8 years: 19.5%, 12 to 14 years: 24.3%). Further, although participation in art and craft decreases from childhood (47.8% of 5 to 8 year-olds), over one-quarter (26.5%) of young people aged 12 to 14 years continue to do artistic activities outside of school hours.

In 2012 and prior years the ABS collected data on children’s participation in cultural and leisure activities, more broadly. In this survey cultural activities were defined as playing a musical instrument, singing, dancing, drama or organised art and craft.20

|

Participated in cultural activities and sport |

Participated in cultural activities only |

Participated in sport only |

Did not participate in cultural activities or sport |

|

|

5 to 8 years |

17.8 |

13.7 |

38.5 |

30.0 |

|

9 to 11 years |

27.1 |

10.4 |

44.0 |

18.5 |

|

12 to 14 years |

23.3 |

10.2 |

42.8 |

23.8 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2012, Children's Participation in Cultural and Leisure Activities, Australia, 2012 – Western Australia, Table 13: Children's participation in organised sport and/or selected organised cultural activities, Selected characteristics

In 2012, most (76.2%) WA young people aged 12 to 14 years participated in some cultural activities or organised sport.

Male children and young people were more likely to be involved in an organised sport than female children and young people. However female children and young people were more likely to be involved in dancing and/or attendance at cultural venues and events.

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Organised art and craft (including dancing) |

22.6 |

45.9 |

33.9 |

|

Attending cultural venues and events |

71.8 |

77.2 |

74.4 |

|

Participating in at least one organised sport |

72.3 |

54.4 |

63.6 |

|

Participating in at least one organised sport and dancing |

72.9 |

66.7 |

69.9 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2012, Children's Participation in Cultural and Leisure Activities, Australia, 2012 – Western Australia, Table 1: Children participating in selected activities, by sex - 2006, 2009 and 2012

No data is available on young people aged 15 to 17 years.

This survey did not consider young people’s involvement in community groups such as scouts, nor did it report on young people’s involvement in religious organisations.

This survey is not planned to be repeated.

Technology and social media

Social media is increasingly being recognised as an important source of connection for young people. Research shows that social media can create positive connections and wellbeing outcomes, while it is also recognised that there can be negative impacts.21

Mobile devices are increasingly used by children and young people for social activities and to build and support social connections. The SOS19 results found that the majority (88.9%) of WA high school students have their own mobile phone.

Female Year 7 to Year 12 students were marginally more likely to have a mobile phone than male Year 7 to Year 12 students (92.7% compared to 88.9%). A greater proportion of young people in the metropolitan area than regional and remote areas had their own mobile phone (metropolitan: 91.6%, regional: 85.9%, remote: 88.5%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

I have this |

88.9 |

92.7 |

91.6 |

85.9 |

88.5 |

90.6 |

|

I don't have this but I would like it |

8.3 |

4.7 |

5.8 |

10.4 |

8.3 |

6.6 |

|

I don't have this and I don't want or need it |

2.8 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

2.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Ninety-five per cent (95.6%) of Year 10 to Year 12 students have their own mobile phone, compared to 86.3 per cent of Year 7 to Year 9 students.

Female students in Year 7 to Year 9 are more likely to have a mobile phone than male Year 7 to Year 9 students (88.7% compared to 83.9%). In Years 10 to 12 there is no significant difference between the proportion of male and female students having their own mobile phone.22

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

I don't have this and I don't want or need it |

4.0 |

1.3 |

|

I don't have this but would like it |

9.7 |

3.1 |

|

I have this |

86.3 |

95.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A marginally lower proportion of Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students have a mobile phone compared to non-Aboriginal students (86.9% compared to 90.9%).

In 2018, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) conducted an online survey to explore how children and young people aged six to 13 years use their mobile phones.23 For young people aged 12 to 13 years, they found the most common uses for mobile phones was to send or receive texts (79.0%), to take photos and videos (77.0%), to use apps (76.0%), to take and receive calls from parents and family (74.0%) and to listen to music (73.0%) and play games (72.0%).24

In September 2020, the eSafety Commissioner conducted a survey of 627 Australian young people aged 12 to 17 years asking them about their social media use. In this survey the most common social media services used by young people were YouTube (72.0%), Instagram (57.0%), Facebook (52.0%) and Snapchat (45.0%).25

Research has found that social media can improve young people’s sense of belonging. In particular, social media enables young people to easily establish or join online groups and communities connecting with other young people who share similar values, beliefs, and interests.26,27 At the same time, social media potentially exposes young people to negative outcomes, such as bullying, ostracism and anxiety.28,29 For more information on WA young people’s negative online experiences refer to the Safe in the community indicator.

Not all young people have access to social media or the internet more broadly. Research has found that Australians with low levels of income, education, and employment are significantly less likely to be digitally connected.30 Digital inclusion is becoming increasingly important for young people to participate fully in society, including to manage their health and wellbeing, access education and services and connect with friends, family and community.31

The increased influence of technology on young people’s lives will be critical to monitor in the future.

Aboriginal young people

Culture is central to the wellbeing of Aboriginal people. There is considerable evidence that highlights the positive associations between culture and wellbeing, including across key indicators such as health, education and employment.32,33 Aboriginal people commonly identify their culture as a factor that builds resilience, moderates the impact of stressful circumstances and supports recovery from adversity. 34,35

In the Commissioner’s consultations, Aboriginal children and young people have explained how culture is particularly important for their wellbeing.36 This includes being connected to country, learning and speaking their own language, respect for elders, sharing and being close to family, listening to stories about culture and taking part in traditional activities and cultural events.37

Aboriginal languages are a critical component of culture and provide Aboriginal children and young people with an important platform for cultural knowledge and heritage to be passed on. Speaking and learning traditional languages improves the wellbeing of Aboriginal children and young people by providing a sense of belonging and empowerment.38

In the Commissioner’s 2015 consultation with Aboriginal children and young people, they spoke about how learning and speaking an Aboriginal language was particularly important to them.39

In SOS19, one-quarter (25.6%) of Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they talk Aboriginal languages at home a lot (7.0%) or some (18.6%).

|

Years 4 to 6 |

Years 7 to 12 |

All |

|

|

A lot |

9.5 |

7.0 |

8.4 |

|

Some |

17.8 |

18.6 |

18.2 |

|

A little bit |

39.8 |

37.5 |

38.8 |

|

None |

32.9 |

36.8 |

34.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

These results are relatively consistent with the 2014–15 ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) which collected data on a range of demographic, social, environmental and economic characteristics, including languages spoken and cultural participation. Data is available on Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 14 years based on parent and carer reports. There is no data for young people aged 15 to 17 years.

In this survey, one-quarter (25.7%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 14 years living in non-remote locations were reported as speaking an Aboriginal language.

The NATSISS survey further reported that two-thirds (66.2%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 14 years living in remote locations speak an Aboriginal language.40 In remote locations, for 30.7 per cent of Aboriginal children aged four to 14 years, the main language spoken at home is an Aboriginal language.41

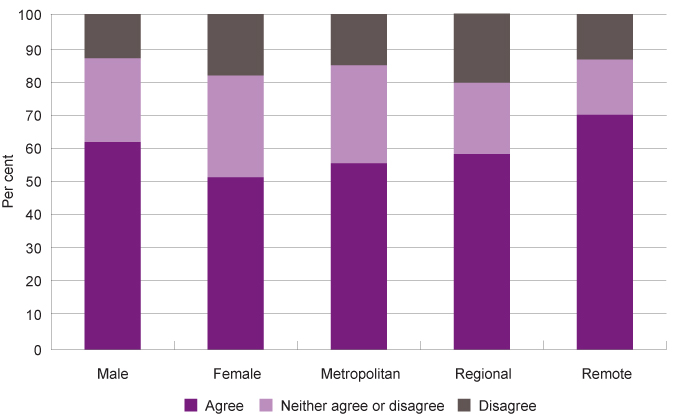

In SOS19, Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students were significantly more likely than non-Aboriginal students to agree a lot they feel like they belong in their community (37.7% compared to 27.2%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Disagree a lot |

6.1 |

6.1 |

|

Disagree a bit |

7.9 |

10.0 |

|

Neither agree or disagree |

20.7 |

27.8 |

|

Agree a bit |

27.7 |

28.9 |

|

Agree a lot |

37.7 |

27.2 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students who feel like they belong in their community by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

In the survey, WA Aboriginal children and young people were asked whether they know their family’s country. Almost three-quarters (73.1%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they know their family’s country, while 5.0 per cent did not know and 21.9 per cent were not sure.

Three-quarters (75.2%) of Year 4 to Year 12 students in the metropolitan area and remote regions (76.1%) reported that they know their family’s country, while a marginally lower proportion of students (69.4%) in regional locations know their family’s country. In regional locations 30.6 per cent of Aboriginal Year 4 to Year 12 students either do not know their family’s country or are not sure (metropolitan: 24.7%, remote: 23.8%).

|

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

No |

6.6 |

8.0 |

5.5 |

6.6 |

|

Yes |

75.2 |

69.4 |

76.1 |

74.2 |

|

I'm not sure |

18.1 |

22.6 |

18.3 |

19.2 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Note: A further breakdown is not possible for this cohort due to the limitations of the sample size.

Of the Year 4 to Year 12 students who know their family’s country, 80.2 per cent spend time on their family’s country. A greater proportion of students in regional and remote areas than the metropolitan area spend time on their family’s country.

|

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

No |

19.1 |

10.9 |

11.2 |

14.8 |

|

Yes |

75.8 |

84.0 |

83.0 |

79.9 |

|

I'm not sure |

5.1 |

5.1 |

5.8 |

5.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Less than one-half (46.0%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students do cultural and traditional activities with their family, this is slightly lower than proportion of students in Years 4 to 6 (51.6%).

|

Years 4 to 6 |

Years 7 to 12 |

|

|

No |

31.1 |

38.2 |

|

Yes |

51.6 |

46.0 |

|

I'm not sure |

17.3 |

15.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Note: A further breakdown is not possible for this cohort due to the limitations of the sample size.

These results differ from the ABS 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) where parents and/or carers reported that almost three-quarters (73.8%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 14 years living in non-remote locations were involved in selected cultural events, ceremonies or organisations in the last 12 months.

In remote areas, a slightly higher proportion (79.8%) of Aboriginal children and young people aged four to 14 years were reported to be involved in selected cultural events, ceremonies or organisations in the last 12 months.42

The difference between the SOS19 results and the findings in the ABS survey may be related to differences in parent-reported and child-reported data, the different form of the question and how it may have been interpreted.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex young people

For lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) young people connection to culture and community is very important. Issues that often affect LGBTI people such as social and cultural beliefs and assumptions about gender and sexuality, including systemic discrimination at an individual, social, political and legal level mean that young people within this group may feel a sense of disconnection from the broader Australian community.

LGBTI young people in the Commissioner for Children and Young People’s 2018 Advisory Committees spoke about their experiences of discrimination, including bullying, public harassment, the use of homophobic and transphobic language, slurs and insults, ‘casual’ homophobia in everyday language, harmful stereotyping about their identity, and discrimination against particular identities within the LGBTI community.43 These experiences of discrimination and social marginalisation often serve to make LGBTI young people feel excluded from the broader community, negatively impacting on their health and wellbeing.

As a result, a sense of connection to culture and community is essential for LGBTI young people. For many LGBTI young people their ‘community’ is the LGBTI community which provides significant support and a sense of identity and belonging.

There is limited data on the social connectedness of WA LGBTI young people.

Australian research has found that LGBTI people living in rural and remote Australian communities are more likely to conceal their sexuality from their peers and have less LGBTI community involvement those living in inner-metropolitan areas.44

For more information on LGBTI young people in WA refer to:

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2019, Issues Paper: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex (LGBTI) children and young people, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Culturally and linguistically diverse young people

For culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) young people connection to culture and community is also important. For this diverse group of young people it is critical they maintain connections to their own culture and community which support their sense of identity and belonging.45,46 It is also important that they are able to develop connections with the broader Australian community to assist in learning a new language, adjusting to a new culture and systems and engaging in school.47,48

Data from the 2016 Census of Population and Housing shows that 17.3 per cent of 0 to 17 year-olds in WA were born in a country other than Australia and New Zealand (Oceania). The most common region of birth after Australia and New Zealand is North-West Europe (3.6%), followed by South-East Asia (2.7%) and Sub-Saharan African (1.8%).49

In WA, 17.5 per cent of people spoke a language other than English at home in 2016. Other than English, Mandarin was the most common with 1.9 per cent of people speaking this language at home. The next most common languages were Italian, Filipino/Tagalog and Vietnamese.50

Some young people from CALD backgrounds (and their families) experience language barriers, feeling torn between cultures, intergenerational conflict, racism and discrimination, bullying and resettlement stress.51 These issues can hinder their ability to feel connected and like they belong in Australia.

In 2016 the Commissioner asked almost 300 children and young people from CALD communities in WA about the positive things in their lives, the challenges they face, their experiences settling in Australia and their hopes for the future.52 These children and young people were asked to rate how easy or hard they found settling in, or ‘fitting in’, to Australia. Just over half of the children and young people who completed this question found settling in ‘quite easy’ or ‘very easy’. A further 38 per cent found settling in ‘okay’.53

In 2017, the University of Melbourne and eight community organisations and government agencies including the Centre for Multicultural Youth conducted the Multicultural Youth Australia Census. In September-October 2017, 1,920 young people aged 15-25 from refugee and migrant backgrounds took part in the survey. Almost two-thirds of the participants were female and 18.8 per cent of participants were from WA.54 This survey found that:55

- nearly three-quarters of multicultural young people participated in civic activities, much of which was on a volunteer basis

- just over half said they feel like they belong to an ethnic community

- one-third had participated in arts, cultural, music or sports activities in the last year

- almost half of multicultural young people had experienced some form of discrimination or unfair treatment in the last 12 months.

For more information on young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and their connections to community and culture refer to the following resources:

Centre for Multicultural Youth 2014, Migrant and refugee young people negotiating adolescence in Australia, Centre for Multicultural Youth.

Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Speak Out, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Office of Multicultural Interests 2009, Not drowning, waving: Culturally and linguistically diverse young people at risk in Western Australia, WA Government

Endnotes

- Noble-Carr D et al 2014, Improving practice: The importance of connections in establishing positive identity and meaning in the lives of vulnerable young people, Children and Youth Services Review, Vol 47, No 3.

- Lenzi M et al 2013, Neighborhood social connectedness and adolescent civic engagement: An integrative model, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol 34.

- Foster CE 2017, Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents, Children and Youth Services Review, Vol 81.

- Lenzi M et al 2013, Neighborhood social connectedness and adolescent civic engagement: An integrative model, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol 34.

- Robinson S et al 2014, In the picture: understanding belonging and connection for young people with cognitive disability in regional communities through photorich research: final report, Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University.

- Wyn J et al 2018, Multicultural Youth Australia Census Status Report 2017/18, Youth Research Centre, University of Melbourne, p. 17-20.

- Morandini J et al 2015, Minority stress and community connectedness among gay, lesbian and bisexual Australians: a comparison of rural and metropolitan localities, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Vol 39, No 3.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Note: Students were able to choose multiple cultural backgrounds, therefore the ‘Australian’ background may include students who also reported having an Aboriginal Australian background.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hoye R et al 2015, Involvement in sport and social connectedness, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Vol 50, No 1, pp. 3–21.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, General Social Survey 2019, Table 3.3 Persons aged 15 years and over, Social Experiences–By Age and Sex, proportion of persons, ABS.

- The definition of ‘cultural activities’ is relatively narrow and does not include some activities within community based groups (for example, attending religious activities).

- Allen K et al 2014, Social Media Use and Social Connectedness in Adolescents: The Positives and the Potential Pitfalls, The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, Vol 31, No 1.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Australian Communications and Media Authority 2019, Kids and mobiles: how Australian children are using mobile phones, Australian Communications and Media Authority [online].

- Ibid.

- eSafety Commissioner 2021, The digital lives of Aussie teens, Australian Government.

- Grieve R et al 2013, Face-to-face or Facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Computers in Human Behavior, Vol 29 No 3.

- Wu Y et al 2016, A Systematic Review of Recent Research on Adolescent Social Connectedness and Mental Health with Internet Technology Use, Adolescent Research Review, Vol 1, No 2.

- Tandoc E et al 2015, Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Science Direct, Vol 43 p 139-146.

- Wu Y et al 2016, A Systematic Review of Recent Research on Adolescent Social Connectedness and Mental Health with Internet Technology Use, Adolescent Research Review, Vol 1, No 2.

- Thomas J et al 2018, Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index 2018, RMIT University.

- Ibid.

- Commonwealth Government 2013, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023, Commonwealth Government, p. 9.

- Dockery AM 2011, Traditional culture and the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians: an analysis of the 2008 NATSISS, Curtin University.

- Zubrick SR et al 2014, Social Determinants of Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Dudgeon P et al (eds) 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice – Second edition, Commonwealth Government, p. 104.

- Bamblett M 2006, Self-determination and Culture as Protective Factors for Aboriginal Children, Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, No 16.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2011, Speaking out about wellbeing: Aboriginal children and young people speak out about culture and identity, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2015, “Listen to Us” Using the views of WA Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people to improve policy and service delivery, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Indigenous Australian Languages [website].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2011, Speaking out about wellbeing: Aboriginal children and young people speak out about culture and identity, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, 4714.0 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, Australia, 2014–15, Table 7.3 Selected characteristics, by remoteness, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 4–14 years, ABS.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2018, Final report: Commissioner for Children and Young People’s 2018 Advisory Committees, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Morandini J et al 2015, Minority stress and community connectedness among gay, lesbian and bisexual Australians: a comparison of rural and metropolitan localities, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Vol 39, No 3.

- WA Office of Multicultural Interests 2009, Not drowning, waving: Culturally and linguistically diverse young people at risk in Western Australia, p. 17.

- Centre for Multicultural Youth 2014, Migrant and refugee young people negotiating adolescence in Australia, Centre for Multicultural Youth.

- Francis S and Cornfoot S 2007, Multicultural Youth in Australia: Settlement and Transition, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

- Centre for Multicultural Youth 2014, Migrant and refugee young people negotiating adolescence in Australia, Centre for Multicultural Youth.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, Census of Population and Housing, 2016, TableBuilder – Dataset 2016 Census – Cultural Diversity, ABS.

- .id the population experts, Western Australia Community Profile – Language Spoken at Home (website), sourced from the ABS 2016 Census.

- WA Office of Multicultural Interests 2009, Not drowning, waving: Culturally and linguistically diverse young people at risk in Western Australia, p. 5.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Speak Out, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid, p. 17.

- Wyn J et al 2018, Multicultural Youth Australia Census Status Report 2017/18, Youth Research Centre, University of Melbourne, p. viii.

- Ibid, p. viii.

Last updated August 2021

In addition to feeling a connection to culture and community, young people need relationships with adults that are stable, caring and supportive, enabling them to ask for help if they have any worries or concerns. It is also important that young people aged 12 to 17 years know how to access help and support from available programs and services.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused sudden and unexpected changes for young people across WA. For many young people in WA, this has been their first experience of significant upheaval to everyday routines and being physically isolated from family members, friends and support networks. Preliminary data shows that due to the pandemic young people are experiencing greater mental health concerns and feeling increasingly worried about school, their future employment prospects and their relationships.1,2

Emotional and health concerns have the potential to impact young people’s behaviours, relationships and ability to learn. Being able to ask for help is a critical skill that supports young people’s mental health and can reduce risk-taking behaviours.3 However, research shows that young people are often hesitant to ask for help.4,5

Help may be informal, through quality interpersonal relationships including parents, neighbours and teachers or through formal systems, such as school psychologists or Kids Helpline.6 Research into resilience highlights the importance of having at least one stable, caring and supportive relationship between a young person and the important adults in his or her life.7

In this measure, the focus is on whether young people know how to get help from a broad range of sources (e.g. websites, health workers etc.). Further information on asking for help or having supportive relationships with parents and other adults are discussed in the Supportive relationships indicator.

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing, including a range of questions getting help or support.8

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

All |

|

|

Doctor |

74.5 |

73.6 |

74.1 |

|

Parent, or someone who acts as your parent |

61.6 |

64.1 |

62.8 |

|

Friend |

47.6 |

58.2 |

52.6 |

|

Teacher |

39.8 |

42.6 |

41.1 |

|

Other family |

40.1 |

27.1 |

34.0 |

|

Internet websites |

23.9 |

42.6 |

32.7 |

|

Brother or sister |

26.5 |

25.7 |

26.1 |

|

Mental health service, like Headspace |

15.2 |

23.7 |

19.2 |

|

Boyfriend or girlfriend |

12.4 |

23.6 |

17.7 |

|

School nurse |

18.2 |

15.8 |

17.1 |

|

School psychologist |

10.3 |

15.7 |

12.9 |

|

School counsellor |

8.1 |

14.4 |

11.0 |

|

School chaplain |

10.2 |

11.7 |

10.9 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

In general, Year 10 to Year 12 students were more likely than Year 7 to Year 9 students to report they found a friend (58.2% compared to 47.6%), internet websites (42.6% compared to 23.9%), a boyfriend or girlfriend (23.6% compared to 12.4%), or a mental health service (23.7% compared to 15.2%) a helpful source of information about health.

In addition, a much greater proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students reported finding talking to friends helpful (60.7% compared to 44.6%) and a mental health service like Headspace (24.0% compared to 14.4%).9

Female students were also significantly more likely than male students to report that in the last 12 months there was a time when they wanted to see someone for their health, but were unable to (35.0% compared to 17.7%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

76.2 |

55.9 |

65.4 |

66.3 |

68.4 |

65.6 |

|

Yes |

17.7 |

35.0 |

27.4 |

23.9 |

25.3 |

26.8 |

|

I don't know |

6.1 |

9.0 |

7.3 |

9.8 |

6.4 |

7.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

There were no significant differences across geographic locations or between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

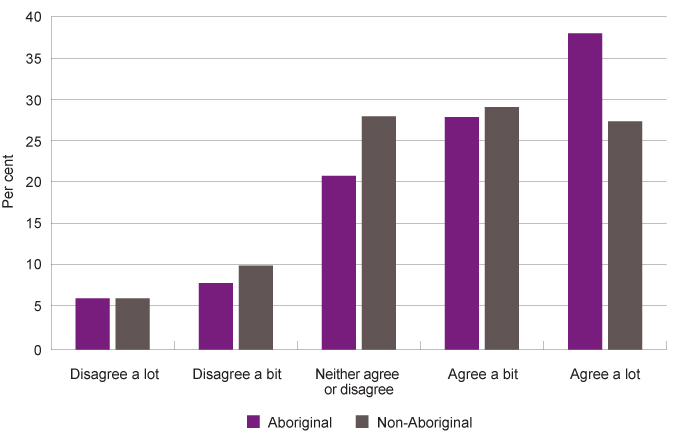

A large proportion (28.5%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that if they needed it they would not know where to get help in their school for mental or emotional health concerns.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

All |

|

|

No |

18.1 |

18.2 |

18.9 |

15.5 |

13.2 |

18.1 |

|

Yes |

71.8 |

71.1 |

70.9 |

73.3 |

74.3 |

71.4 |

|

I don't know |

10.1 |

10.7 |

10.1 |

11.3 |

12.6 |

10.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting that if they needed to get help for stress, anxiety, depression or other emotional health worries they know where to get support in their school, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Furthermore, more than one-third (37.0%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that they do not know where to get help for stress, anxiety, depression or other emotional health worries online.10 There were no significant differences across geographic locations or gender for this question.

In other research, the Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing asked young people aged 13 to 17 years about how often they request and receive help with their problems from services or informally. This survey found that nearly two thirds (62.9%) of all young people had received informal help or support from friends or family members, teachers or other adults in their lives for emotional or behavioural problems in the previous 12 months.11

Teachers can be a supportive adult outside of the family for many young people. The National School Opinion Survey asks students in government schools whether they can talk to teachers about their concerns.

National School Opinion Survey

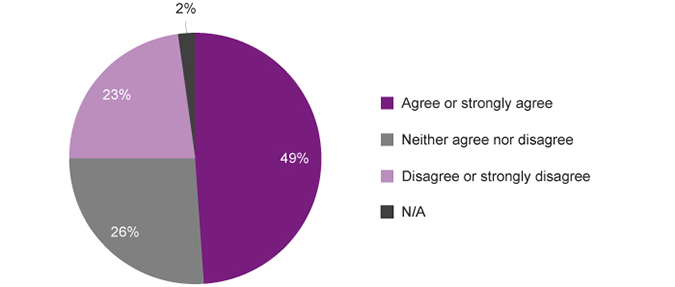

In the 2016 National School Opinion Survey,12 48.6 per cent of participating Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA Government schools either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘I can talk to my teachers about my concerns’. Twenty-six per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, while 23.3 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

National School Opinion Survey, 2016: Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 WA Government school students responding to the statement: ‘I can talk to teachers about my concerns’

Source: National School Opinion Survey 2016, Custom report prepared by WA Department of Education for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

These results represent a substantial drop from primary school where 70 per cent of Year 5 and Year 6 students agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. This shift is consistent with research which shows that children and young people’s help-seeking behaviour changes as they age.13

Similarly, students in SOS19 were asked whether there is a teacher or another adult at school who really cares about them. Among Year 7 to Year 12 students, 61.5 per cent of students felt it was true that at their school there was a teacher or another adult who really cared about them (very much true: 24.3%, pretty much true: 37.2%). Around 30 per cent (28.8%) said this was a little true and one in ten students (9.8%) felt this was not at all true for them.14

In the annual Mission Australia 2020 Youth Survey, 25,800 young people across Australia aged 15 to 19 years responded to questions across a broad range of topics including education and employment, influences on post-school goals, housing and homelessness, participation in community activities, general wellbeing, values and concerns, preferred sources of support, as well as feelings about the future.

In total, 3,098 young people from WA aged 15 to 19 years responded to Mission Australia’s Youth Survey 2020.15 Mission Australia recommend caution when interpreting and generalising the results for certain states or territories because of the small sample sizes and the imbalance between the number of young females and males participating in the survey.

More than one-half of WA respondents (53.8%) were male and 43.3 per cent were female, two per cent were gender-diverse and one per cent preferred not to say. A total of 102 (3.3%) respondents from WA identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.16

The survey asked young people where they go for help with important issues. A significant majority (80.3%) of WA young people responded that they go to their friends for help with issues, with parent or guardian as the next most commonly cited source of help (69.5%). Less than one-half (42.2%) reported that they would go to their GP or health professional or that they would use the internet (45.8%).17

Aboriginal young people

In SOS19, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students had similar responses regarding helpful sources of health information, although Aboriginal students were more likely to find other family (42.5% compared to 33.5%) or brothers or sisters (35.0% compared to 25.6%) helpful. They also found Aboriginal health workers and medical services helpful (29.5% and 24.6%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Doctor |

67.2 |

74.5 |

|

Parent |

50.2 |

63.5 |

|

Friend |

47.6 |

52.8 |

|

Other family |

42.5 |

33.5 |

|

Teacher |

37.8 |

41.3 |

|

Brother or sister |

35.0 |

25.6 |

|

Internet websites |

19.2 |

33.5 |

|

Aboriginal health worked |

29.5 |

0.8 |

|

Aboriginal medical service |

24.6 |

1.0 |

|

School nurse |

21.2 |

16.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished

Aboriginal students were less likely than non-Aboriginal students to find internet websites (19.2% compared to 33.5%) or parents (50.2% compared to 63.5%) helpful.

Aboriginal students were also significantly less likely than non-Aboriginal students to know where to get mental health support online (Aboriginal students: 50.7% No or I don’t know; Non-Aboriginal students: 36.3% No or I don’t know).

This highlights that a greater focus needs to be placed on providing relevant, accessible and culturally safe information for Aboriginal students regarding health and mental health support, in particular online methods (e.g. headspace and Kids Helpline).

No data is available on young people who come from a culturally and linguistically diverse background or young people who identify as LGBTI.

Endnotes

- yourtown and the Australian Human Rights Commission 2020, Impacts of COVID-19 on children and young people who contact Kids Helpline, Australian Human Rights Commission, p. 12.

- Headspace 2020, Coping with COVID: the mental health impact on young people accessing headspace services, Headspace, p. 2.

- Barker F et al 2017, Alcohol, drug and related health and wellbeing issues among young people completing an online screen, Australasian Psychiatry, Vol 25 No 2.

- Rickwood DJ et al 2007, When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia, Vol 187 No 7.

- Lubman D et al 2014, Bridging the gap: Educating family members from migrant communities about seeking help for depression, anxiety and substance misuse in young people, Beyond Blue.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2015, Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience: Working Paper 13, Center for Child Development, Harvard University.

- Ibid.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Lawrence D et al 2015, The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 125.

- All WA Government schools are required to administer parent, student and staff National School Opinion Surveys (NSOS) at least every two years, commencing in 2014. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was responsible for the development and implementation of the NSOS. The WA Department of Education and individual schools can add additional questions to the survey. In WA, the first complete (although non-mandatory) implementation of the survey was conducted in government schools in 2016. The next survey was conducted in 2018. The data should be interpreted with caution as the survey is relatively new and there is a consequent lack of an agreed baseline for results.

- Gray S and Daraganova G 2018, LSAC Annual Statistical Report 2017: Chapter 7 – Adolescent help-seeking behaviour, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Tiller E et al 2020, Youth Survey Report 2020, Mission Australia, p. 183.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 195

Last updated August 2021

At 30 June 2021, there were 1,902 WA young people in care aged between 12 and 17 years, more than one-half of whom (54.0%) were Aboriginal.1

A connection to culture and community and access to support is even more essential for young people in care than other young people. Feeling part of a culture, community or neighbourhood can be very challenging for young people in care as they are living in an environment separate from their family. It can also be difficult for young people in care, who are often highly vulnerable, to access help when they have any concerns or worries.

All children and young people in care are required to have a care plan which identifies their educational, health and cultural needs. In the 2019-20 year 84.0 per cent of children and young people in care had a care plan completed within the required timeframes.2

It is important that all young people in care are able to feel connected to their community and culture, however it is essential for Aboriginal young people, as culture is particularly critical for their identity and wellbeing, and can be difficult to maintain in the child protection system.3 Furthermore, Aboriginal children are significantly overrepresented in the child protection system and are more likely to have permanent placements away from their family and community.4

There are a number of mechanisms that are designed to support Aboriginal young people’s connection to culture while in care. These include compliance with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle and having a cultural support plan, which is a measure under Standard 10 of the National Standards in Out-of-Home Care.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP) consists of five inter-related elements: prevention, partnership, placement, participation and connection. For further information on the ATSICPP and how it can be implemented in practice refer to the SNAICC guide to support implementation.

There is limited data on the experiences of cultural connection for WA Aboriginal young people aged 12 to 17 years in out-of-home care.

There is currently no nationally agreed measure to report on whether children have been placed into care in line with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle.5 Action 1.3 of the Fourth Action Plan of the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children is to develop a nationally consistent approach to measuring the application of the five elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP).

AIHW report on the proportion of Aboriginal children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in out-of-home care placed with extended family or other Aboriginal caregivers (representing compliance with the Placement component of the ATSICPP). In 2018–19, AIHW reported that 61.2 per cent of Aboriginal children and young people in care in WA were placed with Aboriginal relatives or extended family members (kin), other relatives or with other Aboriginal caregivers (including family group homes and residential care run by Aboriginal caregivers).6

For more information on Aboriginal young people in care and their connection to community and support refer to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle measure in the Safe in the home indicator

A cultural support plan is another tool to ensure that Aboriginal children and young people in care remain connected to their culture and country. All Aboriginal children and young people in care are required to have a cultural support plan that outlines how they will be safely supported to maintain contact with their family, friends, community and culture.7

At 30 June 2018, 76.9 per cent of WA Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care had a documented care plan, which includes the cultural support plan.8 That is, more than 20 per cent of Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care in WA did not have a cultural support plan even though it is a Departmental requirement and this result has not improved over the past two years.

Furthermore, a national survey of children and young people aged 10 to 18 years in out-of-home care found that of the 374 Aboriginal children and young people who responded that a cultural support plan was relevant to them, only 17.9 per cent knew if they had a cultural support plan.9

For more information on Aboriginal children and young people in care and their connection to culture refer to:

SNAICC – National Voice for our Children, University of Melbourne and Griffith University 2018, The Family Matters Report 2018, Measuring trends to turn the tide on the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care in Australia, Family Matters.

For further information on children and young people in out-of-home care and the ATSICPP refer to the Safe in the home Indicator.

There is no data available on whether WA young people in care feel sufficiently connected to their culture or community.

Feeling supported by the adults in their daily lives and knowing how to access additional support are key issues for young people in care.

In 2016 the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA explored whether children and young people in care know how to speak up about issues or concerns, and the enabling factors and barriers to raising concerns about issues that affect them. A total of 96 WA children and young people participated in the consultation.10

The children and young people in this consultation nominated their carer, case worker and friends as people they would speak to if they were worried or unhappy about something in their life. They also note that if their concerns are not addressed by the people they confide in, this often reduces their confidence or desire to raise issues in the future.11

Children and young people rarely make official complaints directly; most complaints received by government agencies in relation to children and young people are made on behalf of the child or young person by a parent or another adult.12

In this consultation, strong themes emerged on the barriers to speaking up that many children and young people in care face, including:

- fear of the consequences

- being told not to speak up

- not knowing how to or not having the words to articulate concerns

- not having anyone to speak to or anyone who would listen

- fear of not being believed

- isolation and lack of privacy

- a lack of confidence or feeling scared

- shame

- an imbalance of power.

This highlights how important it is that children and young people in care understand their rights to voice their concerns, are informed on who they can talk to and how they can access help, feel confident and have access to people and services to support them.

In 2018 CREATE Foundation conducted a national survey of children and young people in care where respondents13 were asked “how concerned they felt carers, caseworkers, birth parents, other family members (not living with them), and their friends were in achieving what was best for them.” They found that most of the participants felt that their carers had a high level of concern for them, while they felt their caseworker had less concern, which CREATE noted was disappointing.14

There is no reliable data on the proportion of WA children and young people in care who feel that are supported or know how to get help and support.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2021, Custom report provided by Department of Communities, WA Government [unpublished].

- Department of Communities 2020, Annual Report 2019-20, WA Government p. 225.

- Krakouer J et al 2018, “We Live and Breathe Through Culture”: Conceptualising Cultural Connection for Indigenous Australian Children in Out-of home Care, Australian Social Work, Vol 71, No 3.

- Child Family Community Australia (CFCA) 2019, Child Protection and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018, Indicator Quick Reference Guide: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children – outlines that Placement of Indigenous children (compliance) has no data and that an indicator is still to be developed.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Child Protection Australia 2018–19, Table S5.12: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care, by relationship of carer and state or territory, 30 June 2019, AIHW.

- Department of Social Services 2009, An outline of National Standards for out-of-home care, National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children, p. 12.

- Information provided by the Department of Communities to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- McDowall, JJ 2019, Out of Home Care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of national standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 66.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Speaking Out About Raising Concerns in Care, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People 2021, Child Friendly Complaints Guidelines, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- The survey included 99 children and young people in WA (from a WA population sample size of 1,953). The CREATE report outlines considerable difficulty in recruiting children and young people to participate in the survey and they note that the final samples were not random and the data produced cannot be considered technically ‘representative’. However, they do note that the samples produced were close to the population for age, sex and Aboriginal status. Refer McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation for more information on methodology.

- McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 45.

Last updated August 2021

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates 14,500 WA young people aged 12 to 17 years (7.9%) had reported disability in 2018.1

Young people with disability can find it challenging to feel connected to their community and to feel able to ask for help for any concerns or worries.

People with disability, including children and young people, often experience social exclusion and barriers to meaningful participation in the community.2 For some, this can be the nature of their support needs, however more frequently it is a culture of low expectations, lack of opportunity, inaccessible processes and social and cultural barriers.3

In 2013, the Commissioner consulted with 233 WA children and young people with disability asking them questions about their lives. In this consultation the children and young people highlighted a lack of access to activities such as playing in sport or participating in groups and some felt they did not get enough support to participate fully in school. However, a number of children and young people also reported they were connected and felt part of their community.4

In 2019, the Commissioner conducted the Speaking Out Survey (SOS19) which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of 4,912 Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.5 This survey was conducted across mainstream schools in WA; special schools for students with disability were not included in the sample.

In this survey, Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked: Do you have any long-term disability (lasting 6 months or more) (e.g. sensory impaired hearing, visual impairment, in a wheelchair, learning difficulties)? In total, 315 (11.4%) participating Year 7 to Year 12 students answered yes to this question.

Due to the relatively small sample size, the following results for students who reported long-term disability are observational and not representative of the full population of students with disability in Years 7 to 12 in WA. Comparisons between participating students with and without disability are therefore not statistically significant. Nevertheless, these results provide an indication of the views and experiences of young people with disability.

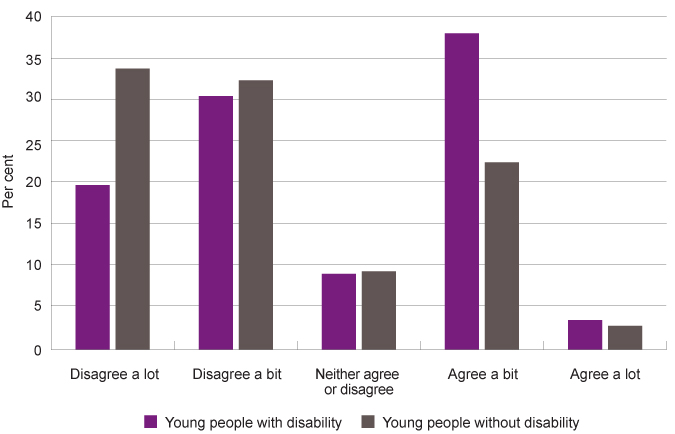

In SOS19 students were asked whether they felt like they belonged in their community, less than one-half (47.7%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students with disability reported that they felt like they belonged in their community.

Students with disability were much less likely to feel they belonged in their community than students without disability (with disability: 47.7%, no disability: 58.9%).

|

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

|

Disagree a lot |

8.4 |

5.4 |

|

Disagree a bit |

11.2 |

9.3 |

|

Neither agree or disagree |

32.7 |

26.3 |

|

Agree a bit |

21.9 |

30.1 |

|

Agree a lot |

25.8 |

28.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Most (59.2%) young people with disability report that their neighbours are friendly and that they like where they live (76.2%).6

Almost one-quarter (24.0%) of young people with disability reported hardly ever or never hanging out with friends when they are not at school (compared to 15.9% of young people without disability).7

Young people with disability were also less likely to practice or play sport than young people without disability.

|

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

|

Every day |

19.6 |

33.5 |

|

Once or twice a week |

30.2 |

32.1 |

|

Less than once or twice a week |

9.0 |

9.3 |

|

Hardly ever |

37.7 |

22.3 |

|

I don't know |

3.5 |

2.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students reporting how much time they spend practising or playing a sport outside of school by disability status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

While in some instances disability can limit physical activities, in the Commissioner’s consultations, children and young people with disability highlighted that they want to play sport or do other activities, but there is limited access to activities including sports and other community activities outside of school.8

Most young people with disability knew where to get support online (64.0%) and at their school (74.3%). These results are similar to young people without disability.

All young people, regardless of the range of their abilities, must be seen as active and valued citizens who have the right to participate in community life to its full extent. This includes their ability to be a part of their community and get help on health and emotional worries when they need it.

Endnotes

- Data is sourced from a custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the Australian Bureau of Statistics based on the 2018 Disability, Ageing and Carers survey. The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities’. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018, Glossary.

- National People with Disabilities and Carer Council, SHUT OUT: The Experience of People with Disabilities and their Families in Australia: National Disability Strategy Consultation Report, Australian Government.

- Simmons C and Robinson S 2014, Strengthening Participation of Children and Young People with Disability in Advocacy, Children with Disability Australia.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2013, Speaking out about disability: The views of WA children and young people with disability, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- Ibid.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People 2013, Speaking Out About Disability: The views of Western Australian children and young people with disability, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

Last updated August 2021

Connection to culture, community and support is critical for the wellbeing of young people aged 12 to 17 years.

Through the Commissioner’s consultations with children and young people across WA, some clear messages have been highlighted about connection to community and culture. Many children and young people said they wanted adults and the broader community to acknowledge the things that were important to them.

Aboriginal children and young people noted that connection to their culture and values were critical to their wellbeing. This included learning about their culture, spending time with their family and listening to stories. A key aspect of Aboriginal peoples’ identity is the deep spiritual connection with the land and their connection to their community.1

Culturally and linguistically diverse children and young people explained how learning English was critical to their sense of belonging and that their family and friends were very important to them. They also wanted more widespread understanding about cultural difference and more culturally appropriate service delivery.2

Other children and young people expressed the need for individualised acknowledgement. They said they wanted to feel personally valued and appreciated.

Many children and young people who have participated in the Commissioner’s various consultations have identified sport, exercise and fitness as among the things that mattered most to them. They also discussed some of the barriers to getting involved in sporting activities that happened outside of school, including transportation, financial costs, inadequate facilities and equipment, a lack of role models, geographic isolation, parental restrictions and study.3

Communities which thrive provide opportunities for young people aged 12 to 17 years to be connected to culture and community in a way that builds supportive relationships and develops their sense of self. Some key policy strategies include:4

- policies and programs which improve and promote access to community-based recreational or cultural activities for young people

- ensuring support services are accessible and engaging, and staff treat all young people with respect, build relationships and are genuinely responsive to their needs

- supporting all young people and their parents, including those with disability and living in regional or remote areas, to overcome barriers to participation in organised sport and other activities

- the creation of more community-based environments that provide space for safe outdoor activities

There are many organisations that provide opportunities for young people to feel connected to their culture and community and offer support if they need it. These include schools, local governments and community-based sporting and other groups. These organisations should be encouraged to be inclusive and accessible for all young people, including those with disability, with culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, who are LGBTI and Aboriginal young people.

Health services and programs, including mental health services, also need to be accessible and visible to young people if they need help.

It is also vital that young people have supportive relationships and feel confident to ask for help if they have any emotional worries or health concerns. Emerging international research highlights that many of the most vulnerable children and young people in a community do not receive the help they need from intensive support services. Rather, the majority of children and young people who receive intensive support services are not those in greatest need.5 However, many vulnerable children and young people do receive more informal assistance and support from civil society and the broader community.6

The broader community, including families, neighbours, school staff and other local community members, play a significant role in supporting vulnerable young people, both to mitigate the need for service intervention early on and later if young people fall through gaps in the service system.

Research into resilience highlights the importance of a young person having at least one stable, caring and supportive adult relationship.7 Opportunities to participate in cultural and community activities that enable young people to build relationships with people outside of their immediate family are therefore important.

Being acknowledged and respected within culture and community is linked to cultural safety which can be defined as ‘an environment that is safe for people: where there is no assault, challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. It is about shared respect, shared meaning, shared knowledge and experience, of learning, living and working together with dignity and truly listening’.8

Cultural safety in health services is about providing quality health care that fits with the cultural values and norms of the person accessing the service, which may differ from the practitioner’s own and/or the dominant culture.9

There remains an ongoing need for a range of holistic Aboriginal-led health and wellbeing programs that draw from, and help to foster, strong cultural connections better supporting Aboriginal families and their children. There also needs to be greater focus on developing the Aboriginal workforce across all settings and the entire service continuum to a level that more adequately reflects the proportion of Aboriginal children and young people who require a program or service.

Ensuring services are culturally safe and inclusive of diversity is important for all young people, but especially for Aboriginal young people, young people who are culturally and linguistically diverse, LGBTI young people and young people with a disability. Young people are more likely to ask for help and access available services if they are respectful and culturally safe places.10,11

Data gaps

There is no publicly available information on whether young people in care feel connected to their communities and cultures and supported if they need help for health or emotional worries.

Endnotes

- Dudgeon P et al 2014, Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research/Kulunga Research Network, p. 5.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2016, Children and Young People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds Speak Out, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People Commissioner for Children and Young People 2018, Policy Brief March 2018: Recreation, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Preventative Health Taskforce 2008, Australia: The Healthiest Country by 2020: A discussion paper prepared by the National Preventative Health Taskforce, Australian Government.

- Little M et al 2015, Bringing Everything I Am Into One Place, Dartington Social Research Unit and Lankelly Chase, p. 50-51.