Academic achievement

Academic achievement is one of the central goals of education and, increasingly, a criterion for measuring school and system effectiveness. Academic achievement and improvement, appropriate to each student’s capabilities, is also essential for young people’s lifetime wellbeing.

However, academic achievement is not the only desirable outcome from high school, and students who may not be achieving academically may be excelling in other areas.

Last updated June 2020

Good data is available on the academic achievement of WA young people aged 12 to 17 years.

Overview

For young people aged 12 to 17 years, academic progress each year is critical. At the same time, high schools should support increasing independence and autonomy, prepare students for further learning and work, encourage connections to community, and support physical and emotional wellbeing.1

In the Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey, 48.7 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA reported that they do above or far above average at school, while 35.8 per cent reported that they do about average.

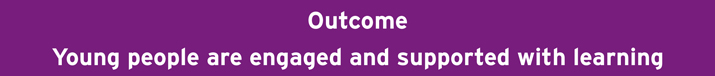

In 2019, NAPLAN results show declines in the proportion of WA students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in Year 7 numeracy and reading and Year 9 reading. In the same year, the proportion of students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in Year 9 numeracy increased marginally.

Year 7 and Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in reading and numeracy, per cent, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

Areas of concern

NAPLAN is the single publicly reported indicator measuring student’s academic achievement. More data is required to measure students’ academic achievement in its broader meaning.

Among WA Year 9 Aboriginal students, 29.7 per cent do not meet the NAPLAN national minimum standard for reading and one-half (50.2%) do not meet the minimum standard for writing.

Only one-third (33.1%) of high school students report that they almost always get extra help from teachers in class if needed.

A lower proportion of female Year 7 to Year 12 students than male students reported that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult at home who believes that they will achieve good things (63.8% female students compared to 71.4% of male students).

Endnotes

- Lamb S et al 2015, Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out, Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute.

Last updated June 2020

Measuring student achievement helps educators and parents understand how children are faring in their learning. Academic achievement measures are also critical to monitor progress, evaluate policies and programs and inform decision-making.

Australia’s academic performance has been in decline since 2000 when compared to other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).1 To improve educational outcomes for Australian children and young people there is a need to reduce the gap between the highest and lowest performing students and enable all students to progress their learning each year.2

Since 2008, all students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 are tested annually using a common assessment tool under the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).3 The NAPLAN national minimum standard is ‘the agreed minimum acceptable standard of knowledge and skills without which a student will have difficulty making sufficient progress at school’.4 This tool is administered by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA).

NAPLAN provides Australia’s first standardised and comprehensive testing system by which to compare and target schools, communities and individual children that may need additional resources and attention. However, the system’s strengths and weaknesses continue being discussed across the parent, teacher and policy and research communities (refer the Grattan Institute paper, Widening gaps: What NAPLAN tells us about student progress for a discussion).

Over-reliance on a single indicator to measure students’ academic performance is problematic and additional indicators are needed to assess students’ academic achievement in its broader meaning. However, no other data from educational bodies on students’ academic performance is currently publicly available.

In this section, we report NAPLAN results for students in Years 7 and 9.5 Data from the Speaking Out Survey 2019 on students’ self-assessed achievement at school is also included.

NAPLAN results for reading

From 2008 to 2019, the proportion of Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in reading increased from 91.8 per cent to 93.6 per cent.

|

Year |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Year 7 |

2008 |

92.7 |

91.0 |

94.5 |

63.4 |

95.0 |

|

2013 |

93.8 |

92.4 |

95.3 |

68.2 |

95.7 |

|

|

2014 |

94.8 |

93.6 |

96.1 |

71.6 |

96.6 |

|

|

2015 |

94.7 |

93.4 |

96.1 |

74.3 |

96.3 |

|

|

2016 |

93.8 |

92.5 |

95.2 |

68.9 |

95.7 |

|

|

2017 |

92.9 |

91.2 |

94.7 |

64.2 |

95.2 |

|

|

2018 |

93.9 |

92.3 |

95.6 |

66.5 |

96.1 |

|

|

2019 |

93.7 |

92.0 |

95.6 |

68.7 |

95.8 |

|

|

Year 9 |

2008 |

91.8 |

90.1 |

93.5 |

62.8 |

94.0 |

|

2013 |

92.9 |

91.4 |

94.4 |

65.7 |

94.8 |

|

|

2014 |

92.9 |

91.1 |

94.8 |

65.9 |

95.0 |

|

|

2015 |

93.2 |

91.4 |

95.1 |

66.9 |

95.1 |

|

|

2016 |

94.0 |

93.2 |

94.8 |

69.4 |

96.0 |

|

|

2017 |

92.7 |

91.1 |

94.3 |

63.9 |

94.9 |

|

|

2018 |

95.0 |

93.8 |

96.3 |

72.5 |

96.7 |

|

|

2019 |

93.6 |

91.9 |

95.4 |

68.3 |

95.6 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

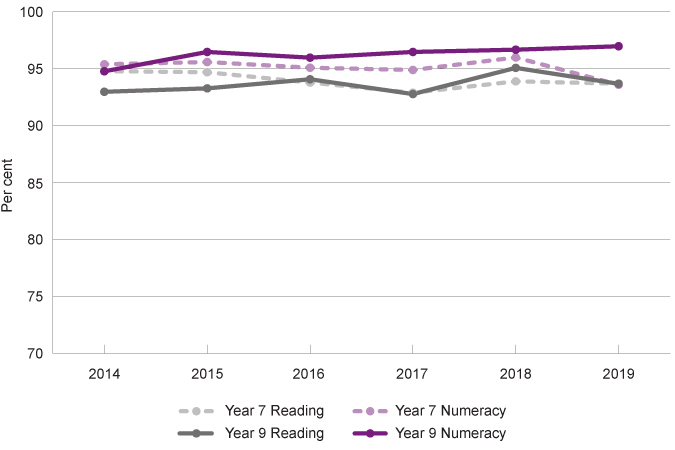

Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in reading, per cent, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

A higher proportion of female than male students achieved at or above the minimum standard in reading across all years.

Following a strong increase in NAPLAN results in reading for Year 9 Aboriginal students from 2017 to 2018 (72.5% up from 63.9%), the 2019 result was somewhat below the 2018 result (68.3% down from 72.5%).

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

|

|

2008 |

94.0 |

62.8 |

94.2 |

70.7 |

|

2013 |

94.8 |

65.7 |

94.5 |

73.9 |

|

2014 |

95.0 |

65.9 |

93.3 |

71.2 |

|

2015 |

95.1 |

66.9 |

93.6 |

71.7 |

|

2016 |

96.0 |

69.4 |

94.0 |

73.6 |

|

2017 |

94.9 |

63.9 |

92.9 |

70.6 |

|

2018 |

96.7 |

72.5 |

94.6 |

73.9 |

|

2019 |

95.6 |

68.3 |

93.1 |

71.7 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

Despite a positive upward trend in reading results for Aboriginal Year 9 students over the last decade, a significant gap remains between the reading results for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students in WA (68.3% of Year 9 Aboriginal students met or exceeded the national minimum standard in 2019 compared to 95.6% of non-Aboriginal students).

When results are disaggregated by Aboriginal status and remoteness area, it becomes evident that location appears to have little effect on non-Aboriginal students, while for Aboriginal students there is a significant decrease in achievement levels relative to a student’s distance from the metropolitan area (achievement levels are the lowest for Aboriginal students in very remote areas).

|

Remoteness area |

Total |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Year 7 |

Metropolitan |

95.2 |

77.6 |

96.0 |

|

Inner regional |

93.6 |

76.0 |

95.2 |

|

|

Outer regional |

90.0 |

67.3 |

94.2 |

|

|

Remote |

84.4 |

63.3 |

94.5 |

|

|

Very remote |

65.9 |

46.9 |

94.1 |

|

|

Year 9 |

Metropolitan |

94.8 |

74.7 |

95.8 |

|

Inner regional |

93.4 |

79.0 |

94.7 |

|

|

Outer regional |

91.7 |

75.9 |

94.8 |

|

|

Remote |

84.7 |

61.3 |

94.1 |

|

|

Very remote |

59.8 |

39.5 |

92.4 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

In 2019, less than one-half of Aboriginal students in Year 7 and Year 9 in very remote locations were achieving at or above the national minimum standard in reading (46.9% of Year 7 and 39.5% of Year 9 students). That is, the majority of Aboriginal students in Year 7 and Year 9 in very remote locations do not meet the minimum benchmark.

These results will be influenced by the high proportion of Aboriginal children and young people who speak Aboriginal languages at home rather than English in very remote regions. For example, the 2016 Census reported that 43.0 per cent of Aboriginal people living in the Kimberley speak more than one language at home6 and the second most spoken language (after English) was Kriol (16.7%).7 These proportions will be higher in the very remote areas of the Kimberley.

NAPLAN results for numeracy

Between 2008 and 2019, the proportion of Year 7 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in numeracy decreased from 94.7 to 93.6, while the proportion of Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in numeracy increased from 92.3 per cent to 96.9 per cent. Analysis of NAPLAN data shows that significant improvement in Year 9 numeracy has been achieved across all student cohorts.

|

Year |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Year 7 |

2008 |

94.7 |

95.0 |

94.5 |

74.2 |

96.5 |

|

2013 |

95.1 |

95.0 |

95.2 |

74.0 |

96.7 |

|

|

2014 |

95.4 |

95.3 |

95.5 |

77.2 |

96.9 |

|

|

2015 |

95.6 |

95.2 |

96.1 |

78.7 |

96.9 |

|

|

2016 |

95.1 |

94.6 |

95.7 |

73.6 |

96.7 |

|

|

2017 |

94.9 |

94.3 |

95.4 |

73.2 |

96.6 |

|

|

2018 |

96.0 |

95.6 |

96.4 |

79.6 |

97.3 |

|

|

2019 |

93.6 |

93.1 |

94.2 |

66.0 |

95.9 |

|

|

Year 9 |

2008 |

92.3 |

92.5 |

92.1 |

66.2 |

94.3 |

|

2013 |

90.8 |

91.5 |

90.1 |

60.6 |

93.0 |

|

|

2014 |

94.7 |

94.6 |

94.9 |

74.2 |

96.4 |

|

|

2015 |

96.4 |

96.3 |

96.5 |

81.3 |

97.5 |

|

|

2016 |

95.9 |

95.5 |

96.2 |

77.6 |

97.4 |

|

|

2017 |

96.4 |

96.2 |

96.7 |

80.4 |

97.7 |

|

|

2018 |

96.6 |

96.4 |

96.9 |

82.5 |

97.7 |

|

|

2019 |

96.9 |

96.5 |

97.3 |

83.5 |

98.0 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

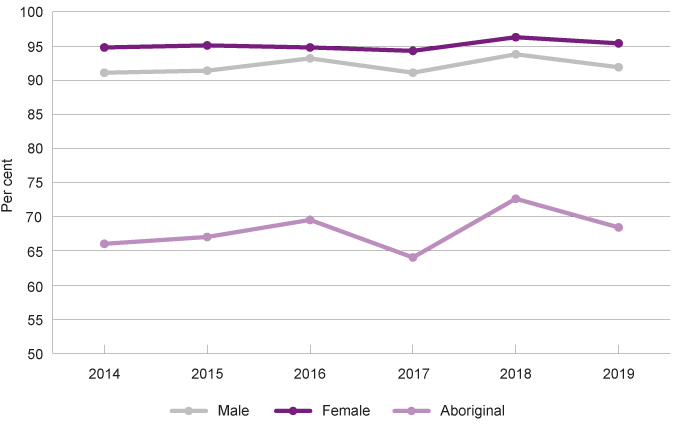

Proportion of Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in numeracy by selected characteristics, per cent, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

The proportion of Aboriginal Year 9 students achieving at or above the national minimum standard has also increased significantly from 66.2 per cent in 2008 to 83.5 per cent in 2019. For Year 7 Aboriginal students, following improvement between 2008 and 2018 (from 74.2% to 79.6%), the result for 2019 of 66.0 per cent represents a significant decrease and is below the level for 2008.

As with reading, numeracy achievement levels declined for Year 7 and Year 9 Aboriginal students relative to students’ distance from the metropolitan area and are particularly low in very remote locations.

|

Remoteness area |

Total |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Year 7 |

Metropolitan |

95.2 |

75.6 |

96.1 |

|

Inner regional |

93.8 |

74.6 |

95.6 |

|

|

Outer regional |

89.4 |

63.0 |

94.2 |

|

|

Remote |

82.8 |

59.7 |

94.0 |

|

|

Very remote |

63.9 |

43.9 |

94.2 |

|

|

Year 9 |

Metropolitan |

97.4 |

86.9 |

98.0 |

|

Inner regional |

97.5 |

92.4 |

98.0 |

|

|

Outer regional |

96.5 |

88.6 |

98.2 |

|

|

Remote |

93.1 |

80.9 |

98.3 |

|

|

Very remote |

76.7 |

64.1 |

97.1 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

Overall, Aboriginal students are at a very high risk of not achieving the minimum standard in comparison to non-Aboriginal students. Across all domains, except numeracy, a substantial proportion of Year 9 Aboriginal students are not meeting the minimum standards.

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

|

|

Reading |

3.3 |

29.7 |

5.2 |

24.9 |

|

Writing |

10.1 |

50.2 |

13.9 |

43.8 |

|

Spelling |

4.5 |

28.5 |

5.1 |

22.0 |

|

Grammar and punctuation |

5.8 |

37.0 |

6.7 |

29.1 |

|

Numeracy |

0.9 |

14.4 |

1.5 |

12.6 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

Note: The table excludes students who were exempt.

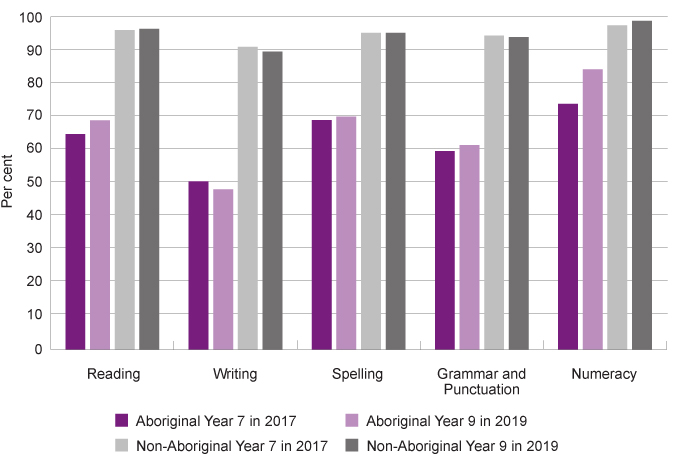

NAPLAN cohort analysis across domains

NAPLAN data allows an assessment of student progress across cohorts, for example, the 2019 Year 9 cohort were the 2017 Year 7 cohort.

Across all domains except writing, the proportion of Aboriginal students in the 2017 Year 7 cohort achieving or exceeding the minimum benchmark marginally increased once they were in Year 9. Of note is the increase in the proportion of Aboriginal students achieving at or above the national minimum standard in numeracy (from 73.2% in 2017 to 83.5% in 2019).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|||

|

Year 7 in 2017 |

Year 9 in 2019 |

Year 7 in 2017 |

Year 9 in 2019 |

|

|

Reading |

64.2 |

68.3 |

95.2 |

95.6 |

|

Writing |

50.1 |

47.7 |

90.2 |

88.8 |

|

Spelling |

68.4 |

69.4 |

94.4 |

94.4 |

|

Grammar and punctuation |

59.1 |

60.9 |

93.6 |

93.1 |

|

Numeracy |

73.2 |

83.5 |

96.6 |

98.0 |

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

Proportion of students achieving at or above the national minimum standard across all domains from Year 7 (2017) to Year 9 (2019) by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2017 and 2019

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, NAPLAN Results

The proportion of non-Aboriginal students from the 2017 Year 7 cohort achieving or exceeding the minimum benchmark across all domains was relatively stable or marginally declined once they were in Year 9.

Monitoring students’ progress across years is important as it highlights where students are not only not achieving the minimum standards, but are also falling further behind each year. Measuring progress tells us about the value the education system adds by indicating what learning takes place in the classroom.8

Multiple factors influence students’ achievement levels. These include socioeconomic status, parental expectations, parents’ educational levels, school advantage and regional differences. For example, it has been found that “bright students in disadvantaged schools show the biggest losses in potential”, making significantly “less progress than similarly capable students in high advantaged schools”.9 Other research has found that “children living in the most advantaged areas will on average achieve more than double the score in national proficiency tests in reading, writing and numeracy than those living in the most disadvantaged areas”.10

For many Aboriginal students, their capacity to learn through the formal education system is impacted by persistent social and economic disadvantage and the ongoing effects of inter-generational trauma.11,12

Speaking Out Survey 2019

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.13

While NAPLAN measures student achievement in literacy and numeracy at a point in time, students in high school are learning many other important skills including creativity, problem-solving and critical thinking. Young people’s views on how well they are doing at school provide an important measure of their broader engagement in learning. In the Speaking Out Survey 2019, Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked ‘In general, how well do you do at school (what are your school results)?’.

In 2019, 48.7 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA reported that they do above or far above average at school, while 35.8 per cent reported that they do about average.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Far above average |

11.8 |

11.2 |

12.1 |

8.4 |

9.9 |

11.4 |

|

Above average |

40.8 |

34.0 |

38.2 |

33.8 |

32.6 |

37.3 |

|

About average |

34.0 |

37.6 |

34.6 |

42.1 |

38.6 |

35.8 |

|

Below the average |

9.6 |

10.9 |

10.0 |

10.6 |

11.3 |

10.1 |

|

Far below average |

2.0 |

3.4 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

2.9 |

|

I'm not sure |

1.8 |

2.9 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

5.5 |

2.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

One-in-eight students reported that they do below (10.1%) or far below (2.9%) average at school, and 2.5 per cent of students were not sure.

A higher proportion of male students than female students reported that they were doing above or far above average (52.6% compared to 45.2%). This difference is not statistically significant.

A significantly lower proportion of Aboriginal students than non-Aboriginal students felt they were doing well at school, with 30.1 per cent of Aboriginal students saying they were doing above or far above average compared to 49.8 per cent of non-Aboriginal students who said the same.

|

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

|

|

Far above average |

11.8 |

5.7 |

|

Above average |

38.0 |

24.4 |

|

About average |

35.2 |

46.6 |

|

Below the average |

10.1 |

11.7 |

|

Far below average |

2.8 |

4.3 |

|

I'm not sure |

2.2 |

7.3 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Research has found that stress related to education and schoolwork can have a negative impact on student’s learning capacity, academic achievement and physical and mental health.14 Stress and anxiety related to schoolwork are also negatively related to life satisfaction more broadly.15

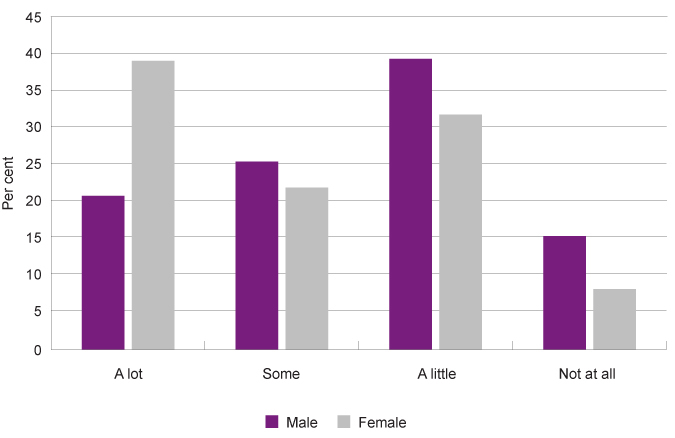

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked ‘How pressured do you feel by the schoolwork you have to do?’. One-third of students (29.6%) reported feeling a lot of pressure due to their schoolwork and 23.3 per cent reported feeling some pressure.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

A lot |

20.6 |

38.7 |

30.4 |

29.8 |

16.9 |

29.6 |

|

Some |

25.2 |

21.7 |

24.2 |

21.4 |

15.7 |

23.3 |

|

A little |

39.0 |

31.5 |

33.8 |

37.5 |

51.5 |

35.2 |

|

Not at all |

15.2 |

8.1 |

11.7 |

11.4 |

15.9 |

11.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Almost double the proportion of students in the metropolitan area felt a lot of pressure due to their schoolwork compared to students in remote areas (30.4% compared to 16.9%).

A significantly higher proportion of female students than male students reported feeling pressure due to their schoolwork, with 38.7 per cent of female students feeling a lot of pressure, compared to 20.6 per cent of male students. Conversely, a higher proportion of male students compared to female students reported feeling not at all pressured by their schoolwork (15.2% compared to 8.1%).

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students saying they feel a lot, some, a little or not at all pressured by the schoolwork they have to do by gender, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Non-Aboriginal students were more likely to report feeling a lot of pressure due to their schoolwork than Aboriginal students (30.1% compared to 20.1%).

|

Non-Aboriginal |

Aboriginal |

|

|

A lot |

30.1 |

20.1 |

|

Some |

23.6 |

17.7 |

|

A little |

34.7 |

44.4 |

|

Not at all |

11.5 |

17.7 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Students in Years 10 to 12 were significantly more likely than students in Years 7 to 9 to report feeling a lot of pressure due to their schoolwork (37.0% compared to 23.0%).

|

Years 7 to 9 |

Years 10 to 12 |

|

|

A lot |

23.0 |

37.0 |

|

Some |

21.9 |

24.9 |

|

A little |

40.9 |

28.9 |

|

Not at all |

14.2 |

9.2 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

For more information on young people’s mental health refer to the Mental health indicator for age group 12 to 17 years.

Endnotes

- Gonski D et al 2018, Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, p. viii.

- Ibid, p. x.

- It should be noted that NAPLAN will not proceed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and related community restrictions and responses. Refer Education Council communique for more information.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2016, NAPLAN Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy. National Report for 2016, ACARA, p. v.

- NAPLAN is in the process of transitioning from a paper test to an online test. In 2018, the majority of students took NAPLAN on paper however, approximately 15 per cent of students nationally sat NAPLAN online, with variances to this figure in each state and territory.[1] In 2019, around 50 per cent of schools nationally undertook NAPLAN online. The governing body ACARA advises that for the 2018 and 2019 transition years, the ‘online test results were equated with the pen-and-paper tests. Results for both the tests are reported on the same NAPLAN assessment scale. NAPLAN results, however, should always be interpreted with care.’ This is particularly the case in 2019 as ‘some students experienced disruptions due to connectivity issues’. Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2019, NAPLAN Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy, National Report for 2019, ACARA, p. v.

- In comparison, the 2016 Census reported that 75.2 per cent of all people in WA only spoke English at home. Source: ABS, QuickStats: Western Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2017, 2016 Census: Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Peoples QuickStats: Kimberley, ABS [website].

- Goss P et al 2018, Measuring student progress: A state-by-state report card, Grattan Institute.

- Goss P and Sonnemann J 2016, Widening gaps: What NAPLAN tells us about student progress, Grattan Institute, p. 31

- Cassells R et al 2017, Educate Australia Fair?: Education Inequality in Australia, Focus on the States Series, Issue No. 5, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, p. 68

- SNAICC – National Voice for our Children 2018, Family Matters Report 2018, SNAICC, p. 10.

- Gillan K et al 2017, The Case for Urgency: Advocating for Indigenous voice in education, Australian Council for Educational Research, p. 2.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Pascoe MC et al 2020, The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, Vol 25, No 1.

- OECD 2017, PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being, PISA, OECD Publishing, p 84.

Last updated June 2020

Students require different levels and types of support to assist them with their learning and to enable their ongoing engagement with education. Teachers who provide help for learning are valued by students as it enables improved access to the curriculum, reduced anxiety and facilitates experiences of success.

Further, family engagement in learning is strongly related to students’ academic, social, emotional and behavioural outcomes. Studies have shown that when families are involved in their child’s education and engaged with their school, student outcomes are improved.1,2

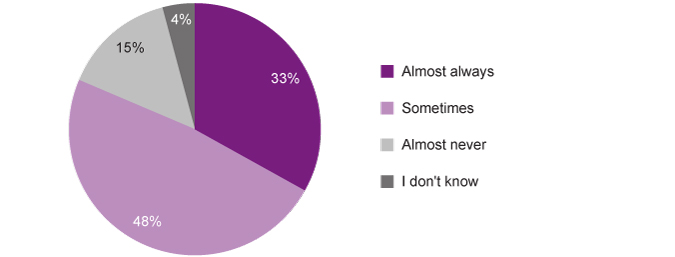

Help in the classroom

In the Commissioner’s 2019 Speaking Out Survey, one-third (33.1%) of students reported almost always getting extra help from teachers in class if needed. Almost one-half (48.3%) of students said they get extra help sometimes, while 14.5 per cent of students reported almost never getting the extra help they need to do their classwork.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Almost always |

35.8 |

30.7 |

33.2 |

34.4 |

28.6 |

33.1 |

|

Sometimes |

47.3 |

49.8 |

47.5 |

49.8 |

56.6 |

48.3 |

|

Almost never |

12.6 |

15.8 |

15.2 |

12.1 |

10.4 |

14.5 |

|

I don't know |

4.3 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

4.4 |

4.1 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to 12 students reporting they get extra help from teachers with their work in class (if needed) almost always, sometimes, almost never or they don’t know, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

No significant differences were found between male and female students, students in different geographic areas or between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

A significant decrease in the proportion of students reporting they almost always get extra help from their teachers was measured from primary school to high school (50.3% of Year 4 to Year 6 students compared to only 33.1% of Year 7 to Year 12 students). Correspondingly, the proportion of students who reported they almost never get help from their teachers increased between these year groups (from 6.6% in Years 4 to 6 to 14.5% in Years 7 to 12).3

These shifts are likely reflecting the different teaching practices and pedagogies employed in secondary school, however, they give cause for concern that during the critical transition period from primary to secondary school a significant proportion of students feel as if they are not receiving the support they need for learning.

National School Opinion Survey

In the 2016 National School Opinion Survey,4 65.0 per cent of participating Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA government schools either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘my teachers provide me with useful feedback about my schoolwork’. Twenty two per cent neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement, while 11.0 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed.5

Parental engagement in students’ learning

Students participating in the Speaking Out Survey 2019 were asked a range of questions about their family’s involvement with school.

Parent involvement with school generally declines in secondary school, however, more than one-half (53.5%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that their parents or someone in their family often ask about their schoolwork with an additional 30.0 per cent saying they get asked sometimes. Around one-in-ten students (12.1%) said their parents ask rarely about this and the remaining 3.7 per cent said never.6

In the School and Learning Consultation of 2016, 60.0 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that someone in their family helps them with their homework ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’, while 10.0 per cent of students answered that they do not require help. The remaining 30.0 per cent of students said that they ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ receive help with homework from someone in their family.7

For further information refer to the Commissioner’s School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report.

Endnotes

- Emerson L et al 2012, Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY).

- Desforges C and Abouchaar A 2003, The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review, Research Report No 433, Department for Education and Skills UK.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables. Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, [unpublished].

- All WA government schools are required to administer parent, student and staff National School Opinion Surveys (NSOS) at least every two years, commencing in 2014. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was responsible for the development and implementation of the NSOS. The WA Department of Education and individual schools are also able to add additional questions to the survey. In WA, the first complete (although non-mandatory) implementation of the survey was conducted in government schools in 2016. The next survey was conducted in 2018 and results will be published once compiled. The data should be interpreted with caution as the survey is relatively new and there is a consequent lack of an agreed baseline for results.

- Results from the National School Opinion Survey 2016, custom report prepared by WA Department of Education for Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables. Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, [unpublished].

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2018, School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 91.

Last updated June 2020

Schooling does not occur in isolation for children and young people. They bring with them the impact of their circumstances, shaped by economic, environmental and social factors. These circumstances can sometimes give rise to emotional concerns which have the potential to impact student thinking, learning, behaviour and relationships. Emotional support facilitates learning and social and emotional development, particularly if provided when children or young people are facing challenges.1 Support may be informal, through quality interpersonal relationships or formal systems, such as school psychologists.

There is limited data on the number or proportion of students who receive support to help them manage emotional or other non-schoolwork issues at school.

In the Speaking Out Survey 2019, just over 60 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students felt it was either very much true (24.3%) or pretty much true (37.2%) that there is a teacher or another adult at their school who really cares about them. The remaining students said this was only a little true (28.8%) or not at all true (9.8%).

These results represent a significant change to the answers of students in Year 4 to Year 6 where 82.5 per cent of students felt that there was a teacher or another adult at their school who really cared about them (61.5% for Year 7 to Year 12).

According to the results of the Speaking Out Survey, Year 7 to Year 12 Aboriginal students were significantly more likely than non-Aboriginal students to report that it was very much true that there was a teacher or another adult at their school who really cared about them (34.6% Aboriginal compared to 23.6% non-Aboriginal).

For more information refer to the indicator: A sense of belonging and supportive relationships at school.

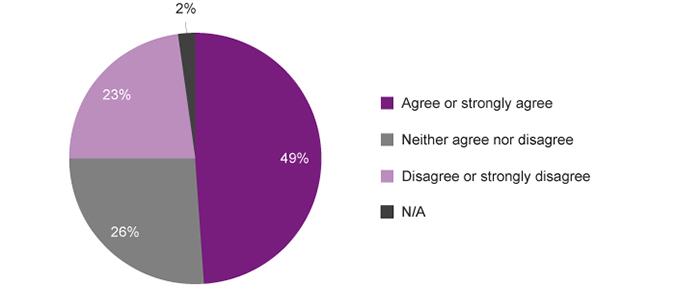

National School Opinion Survey

In the 2016 National School Opinion Survey,2 48.6 per cent of participating Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA government schools either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘I can talk to my teachers about my concerns’. Twenty-six per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, while 23.3 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

National School Opinion Survey: Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 WA government school students responding to the statement: ‘I can talk to teachers about my concerns’, per cent, WA, 2016

Source: National School Opinion Survey 2016, Custom report prepared by WA Department of Education for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

These results represent a significant drop from primary school where 70.0 per cent of Year 5 and Year 6 students agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2015, Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience: Working Paper 13, Center for Child Development, Harvard University.

- Source: Results from the National School Opinion Survey 2016, custom report prepared by WA Department of Education for Commissioner for Children and Young People WA. All WA government schools are required to administer parent, student and staff National School Opinion Surveys (NSOS) at least every two years, commencing in 2014. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was responsible for the development and implementation of the NSOS. The WA Department of Education and individual schools are also able to add additional questions to the survey. In WA, the first complete (although non-mandatory) implementation of the survey was conducted in government schools in 2016. The next survey was conducted in 2018 and the results will be published when available. The data should be interpreted with caution as the survey is relatively new and there is a consequent lack of an agreed baseline for results.

Last updated June 2020

Research suggests that teachers’ expectations of their students do not merely forecast student outcomes, but that they can also influence outcomes; that is, low (or high) expectations can modify student behaviour.1 In the School and Learning Consultation, participating students identified that teachers who support and encourage them to do their best and talk about their aspirations, increase students’ motivation to engage.2

Expectations of teachers and other school staff

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, 84.4 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students felt it was either very much (51.1%) or pretty much (33.3%) true that there is a teacher or another adult at their school who expects them to do well. Almost 16 per cent of students reported that this is only a little (11.2%) or not at all (4.4%) true for them.

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Very much true |

51.1 |

51.1 |

51.0 |

50.5 |

55.1 |

51.1 |

|

Pretty much true |

33.3 |

33.7 |

33.2 |

33.9 |

33.1 |

33.3 |

|

A little true |

11.4 |

10.9 |

11.2 |

11.6 |

9.6 |

11.2 |

|

Not at all true |

4.3 |

4.2 |

4.7 |

4.0 |

2.2 |

4.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

No significant differences were measured in regard to this question for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students, for male and female students, or for students in different geographic areas.3

National School Opinion Survey

In the 2016 National School Opinion Survey,4 89.0 per cent of participating Year 7 to 12 students in government schools either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, ‘my teachers expect me to do my best’. Six per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, while three per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed.5

Parental expectations

Research shows that there is a strong relationship between parental aspirations and expectations and the child’s actual academic outcomes.6 Evidence also suggests that parental expectations for children’s academic achievement predict educational outcomes more than other measures of parental involvement, such as attending school events.7

In the Commissioner’s 2016 School and Learning Consultation, high expectations from family members were generally seen as a positive influence for school and learning, however, students were careful to temper comments with provisos such that expectations must be related to the student’s ability and interest, and facilitated by support from family members. Low expectations, negative comments or ‘put downs’ from family members were discouraging and hurtful for students and not helpful for how they felt about attending school and learning.8

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, over two-thirds (67.4%) of Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that it is very much true that there is a parent or another adult at home who believes that they will achieve good things. Around 11 per cent of Year 7 to Year 12 students feel this is only a little true (8.3%) for them or not at all (2.5%).

|

Male |

Female |

Metropolitan |

Regional |

Remote |

Total |

|

|

Very much true |

71.4 |

63.8 |

67.5 |

67.8 |

65.3 |

67.4 |

|

Pretty much true |

19.7 |

23.9 |

22.0 |

20.3 |

23.5 |

21.8 |

|

A little true |

6.9 |

9.8 |

8.1 |

9.5 |

8.9 |

8.3 |

|

Not at all true |

2.1 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

A lower proportion of female students than male students reported that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult at home who believes that they will achieve good things (63.8% female students compared to 71.4% of male students). This difference was not statistically significant.

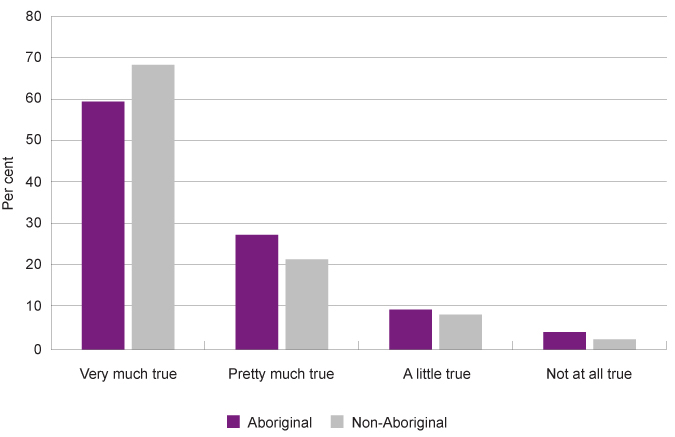

A significantly lower proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal Year 7 to Year 12 students reported that it was very much true that there is a parent or another adult at home who believes that they will achieve good things (59.1% of Aboriginal students compared to 67.9% of non-Aboriginal students).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

Very much true |

59.1 |

67.9 |

|

Pretty much true |

27.3 |

21.5 |

|

A little true |

9.5 |

8.3 |

|

Not at all true |

4.1 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 students saying it is very much true, pretty much true, a little true or not at all true that there is a parent or another adult at home who believes that they will achieve good things by Aboriginal status, per cent, WA, 2019

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Endnotes

- Gershenson S and Papageorge N 2018, The power of teacher expectations: how racial bias hinders student attainment, Education Next, winter 2018, Vol 18, No 1.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People 2018, School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p 77.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

- All WA government schools are required to administer parent, student and staff National School Opinion Surveys (NSOS) at least every two years, commencing in 2014. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was responsible for the development and implementation of the NSOS. The WA Department of Education and individual schools are also able to add additional questions to the survey. In WA, the first complete (although non-mandatory) implementation of the survey was conducted in government schools in 2016. The next survey was conducted in 2018 and results will be published when available. The data should be interpreted with caution as the survey is relatively new and there is a consequent lack of an agreed baseline for results.

- Sourced from custom report on results from the National School Opinion Survey 2016 prepared by WA Department of Education for Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Emerson L et al 2012, Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY).

- Child Trends Databank 2014, Parental Expectations for their Children’s Educational Attainment.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People 2018, School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p 104.

Students’ perceptions of the relevance and value of educational content influence their engagement in school, learning and learning behaviours. Given these perceptions are partly framed by the curriculum and the way it is taught, listening to students’ views on the curriculum content and its relevance are essential considerations for enhancing engagement with school and learning.

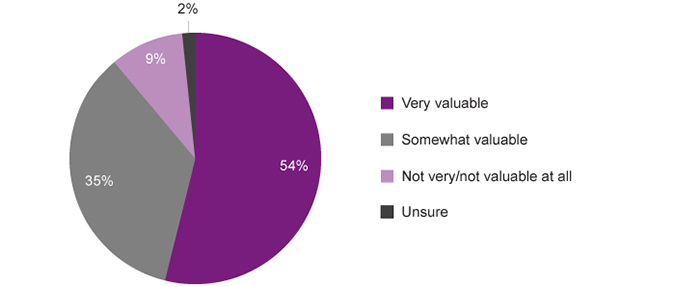

In the Commissioner’s 2016 School and Learning Consultation, a little more than one-half of Year 7 to Year 12 students (54.0%) reported that what they are learning at school is ‘very valuable’ to them and their future, and one-third (35.1%) said that it is ‘somewhat valuable’ to them. However, one-in-ten (9.4%) students in Year 7 to Year 12 said they feel that what they are learning at school is ‘not very valuable’ or ‘not valuable at all’ to their future.

Proportion of Year 7 to Year 12 WA students saying what they are learning at school is very valuable, somewhat valuable, not very valuable/not valuable at all or they are unsure

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2018, School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report

There were no significant differences between male and female students, students in regional and metropolitan areas, and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

However, male students in metropolitan areas were significantly more likely than male students in regional areas to say that what they are learning at school is ‘very valuable’ to them (61.8% compared to 45.7%). The same difference was not found within female students in metropolitan and regional areas (53.1% compared to 52.7%).

Students who felt that what they were learning was valuable to them cited the following reasons:

- It will help me get a job (83.4%)

- It will enable me to do more study/go to university (72.5%)

- I enjoy learning (49.0%)

Those students who felt that what they were learning had little to no value to them cited the following reasons:

- I have other interests (60.9%)

- It will not help me get a job (48.4%)

Some of these students also described difficulties in seeing the relevance or connection between what they were learning at school and the ‘real world’ and their dreams and aspirations for the future.

National School Opinion Survey

In the 2016 National School Opinion Survey,1 66.0 per cent of participating Year 7 to Year 12 students in WA government schools either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, ‘my school gives me opportunities to do interesting things’. Nineteen per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, while 13.0 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

There was little difference between the responses of male and female Year 5 to 12 students or for students in different geographic locations. Aboriginal Year 5 to Year 12 students were less likely to respond with agreed or strongly agreed than non-Aboriginal students (67.0% compared to 73.0%).

This data item has only limited relevance for this measure as ‘interesting things’ could be interpreted very differently by different young people and these things may or may not develop useful skills and knowledge.

Endnotes

- Source: Results from the National School Opinion Survey 2016, custom report prepared by WA Department of Education for Commissioner for Children and Young People WA. All WA government schools are required to administer parent, student and staff National School Opinion Surveys (NSOS) at least every two years, commencing in 2014. The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was responsible for the development and implementation of the NSOS. The WA Department of Education and individual schools are also able to add additional questions to the survey. In WA, the first complete (although non-mandatory) implementation of the survey was conducted in government schools in 2016. The next survey was conducted in 2018 and results will be published when available. The data should be interpreted with caution as the survey is relatively new and there is a consequent lack of an agreed baseline for results.

Last updated June 2020

At 30 June 2019, there were 2,420 WA young people in care aged between 10 and 17 years, more than one-half of whom (53.3%) were Aboriginal.1

There is limited data on the academic achievement of WA young people in care aged 12 to 17 years.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) studied the academic performance of children and young people in care across Australia in 2013, by linking the data from the Child Protection National Minimum Data Set (CP NMDS) and the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). Among the study population, National Minimum Standard achievement rates varied across the five assessment domains (reading, writing, spelling, grammar and punctuation, and numeracy). Minimum standard achievement rates ranged between 56 and 75 per cent for Year 7, and 44 to 69 per cent for Year 9 students.2 This data was not disaggregated by state.

These proportions are significantly lower than those for students who are not in out-of-home care (e.g. around 95% for Year 7 and Year 9 reading and numeracy). However, as AIHW note, the academic achievement of children and young people in care is likely to be affected by complex personal histories and multiple aspects of disadvantage (including poverty, maltreatment, family dysfunction and instability in care and schooling).3 Nevertheless, when removing a child from their family and placing them into care it is critical that their lifetime outcomes are improved as a result, and educational achievement is a key component of this.

In 2017, CREATE Foundation asked 1,275 Australian children and young people aged 10 to 17 years about their lives in the care system. CREATE Foundation noted that the recruitment of participants proved difficult and this resulted in a non-random sample with the possibility of bias.4

The survey found that 54.4 per cent of respondents would like additional support to help them do well at school. Of these, 29.8 per cent requested extra help with schoolwork and 23.3 per cent requested extra help with homework. A significant proportion (17.4%) also noted they would like additional financial support and resources (e.g. computers and tablets).5 This survey data is not available by jurisdiction or age group.

Other Australian research suggests that support from carers and their caseworkers most strongly predicted school engagement for children and young people in care.6 This research also found that children and young people in care reported lower aspirations for themselves and saw their parents as having lower aspirations for them, than children and young people not in care.7

Young people in care experience high vulnerability and educational risk and there must be a continued focus on improving the support provided to them to access school and learning.

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018–19, WA Government p. 26.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015, Educational outcomes for children in care: Linking 2013 child protection and NAPLAN data, Cat No CWS 54, AIHW, p. 7.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015, Educational outcomes for children in care: Linking 2013 child protection and NAPLAN data, Cat No CWS 54, AIHW.

- McDowall JJ 2018, Out-of-home care in Australia: Children and young people’s views after five years of National Standards, CREATE Foundation, p. 17-19.

- Ibid, p. 82.

- Tilbury C et al 2014, Making a connection: school engagement of young people in care, Child & Family Social Work, Vol 19, No 4.

- Ibid, p. 463.

Last updated June 2020

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018 data collection reports that approximately 30,200 WA children and young people (9.2%) aged five to 14 years have reported disability.1,2

Students with disability commonly attend either special schools that enrol only students with special needs, special classes within a mainstream school or mainstream classes within a mainstream school (where students with disability might receive additional assistance).3

In 2018, almost all Australian school children aged five to 14 years with disability attended school (95.8%). Of these, around 70.0 per cent attend mainstream schools, 20.0 per cent attend special classes within a mainstream school and 11.3 per cent attend special schools.4

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities requires that children with disability shall be given the assistance required to participate effectively in education and training and to be prepared for employment conducive to the child’s individual development.5

It is also a national requirement under the Disability Standards for Education 2005 that students with disability can access and participate in education on the same basis as other students. A key aspect of the standards is that education providers must make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to ensure that a student with disability has comparable opportunities and choices with those offered to students without disability.6

Reasonable adjustments may include changes to the way that teaching and learning is provided, changes to the classroom or school environment, the way that students’ progress and achievements are assessed and reported to parents, the provision of personal care and planning to meet individual needs, as well as professional learning for teachers and support staff.

The Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability in Education provides a summary of students receiving an adjustment for disability across Australia.7 The data for WA shows that in 2019, one in five WA students received an adjustment for disability.

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Support with Quality Differentiated Teaching Practice* |

8.9 |

9.2 |

8.9 |

|

Supplementary** |

8.3 |

7.6 |

7.5 |

|

Substantial*** |

2.5 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

|

Extensive**** |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

|

All adjustments |

20.5 |

19.9 |

19.8 |

Source: ACARA, School Students with Disability

Notes: (Source: NCCD Selecting the level of adjustment)

* Students with disability are supported through active monitoring and adjustments that are not greater than those used to meet the needs of diverse learners. These adjustments are provided through usual school processes, without drawing on additional resources.

** Students with disability are provided with adjustments that are supplementary to the strategies and resources already available for all students within the school.

*** Students with disability who have more substantial support needs are provided with essential adjustments and considerable adult assistance.

**** Students with disability and very high support needs are provided with extensive targeted measures and sustained levels of intensive support. These adjustments are highly individualised, comprehensive and ongoing.

Cognitive disability is the most common category of disability for children and young people receiving adjustments at school (58.7% of students receiving adjustments have cognitive disability).

|

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Cognitive |

57.6 |

57.2 |

58.7 |

|

Physical |

24.2 |

22.9 |

20.2 |

|

Sensory |

4.0 |

3.9 |

3.5 |

|

Social-emotional |

14.1 |

16.0 |

17.7 |

|

All |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

Source: ACARA, School Students with Disability

Note: If a student has multiple disabilities, teachers and school teams determine which disability category has the greatest impact on the student’s education and is the main driver of adjustments to support the student’s access and participation.

Children and young people with cognitive disability can include those with autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and Down syndrome.

While the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability in Education provides information on the number of children and young people receiving adjustments for disability, it does not report on the educational outcomes or experiences of students with disability.

Measuring educational outcomes for children and young people with disability and/or long-term health issues is challenging.8 Experts recommend that when using standardised testing (such as NAPLAN), an accommodated or alternative assessment is available for children and young people with special educational needs.9 This is not currently available within NAPLAN, and while NAPLAN is a standardised process for all students to complete, evidence suggests that children and young people with disability often do not participate.10

For those students who are participating in the NAPLAN assessments, ACARA does not disaggregate the results to report specifically on the results of children and young people with disability. Therefore, there is limited ability to measure whether current policies and practices are supporting the educational progress of students with disability.

Speaking Out Survey 2019

In 2019, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (the Commissioner) conducted the Speaking Out Survey which sought the views of a broadly representative sample of Year 4 to Year 12 students in WA on factors influencing their wellbeing.11 This survey was conducted across mainstream schools in WA; special schools for students with disability were not included in the sample.

In this survey, Year 7 to Year 12 students were asked: Do you have any long-term disability (lasting 6 months or more) (e.g. sensory impaired hearing, visual impairment, in a wheelchair, learning difficulties)? In total, 315 (11.4%) participating Year 7 to Year 12 students answered yes to this question.

Due to the relatively small sample size, the following results for students who reported long-term disability are observational and not representative of the full population of students with disability in Years 7 to 12 in WA. Comparisons between participating students with and without disability are therefore observational and not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the results provide an indication of the views and experiences of young people with disability.

All students were asked: In general, how well do you do at school (what are your school results)? Among students with disability, 8.3 per cent thought they were far above average, 35.1 per cent above average, 33.3 per cent about average, 13.6 per cent below average and 6.9 per cent far below average.

|

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

|

Far above average |

8.3 |

12.2 |

|

Above average |

35.1 |

39.0 |

|

About average |

33.3 |

35.6 |

|

Below average |

13.6 |

9.3 |

|

Far below average |

6.9 |

2.1 |

|

I'm not sure |

2.7 |

1.8 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

These results are broadly similar to those for students without disability with two exceptions: the proportion of students saying they are below or far below average was higher for students with disability than without (with disability: 20.6% compared to without disability 11.4%). Further, a higher proportion of students without disability reported being far above average (8.3% with disability compared to 12.2% without disability).

Getting extra help from teachers in class is important for all students and especially for those with disability. In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, one-third (35.8%) of students with disability reported almost always getting extra help from teachers in class if needed, and forty per cent (41.1%) of students said they get extra help sometimes.

|

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

|

Almost always |

35.8 |

33.6 |

|

Sometimes |

41.1 |

48.9 |

|

Almost never |

18.6 |

13.8 |

|

I don't know |

4.6 |

3.6 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

One-in-five (18.6%) students with disability said they almost never get extra help when they need it, compared to 13.8 per cent of students without disability.

The 2015 Federal Senate Inquiry into the education system for children with disability found that there were low or, in some cases, no expectations of students with disabilities. That is, educators and students often fail to recognise students with disabilities as capable of learning to their full potential.12

Similar to children without disability, parental expectations of children with disability have been shown to have a significant, yet sometimes detrimental, influence on children’s academic outcomes. This is partly due to the disability ‘label’ which has a range of negative implications, particularly on children’s self-concept which influences social and academic outcomes.13

In the 2019 Speaking Out Survey, when asked if there is a teacher or another adult at school who expects them to do well, more than one-half (56.6%) of students with disability reported this was very much true (students without disability: 52.0%). At the same time, 5.9 per cent of student with disability reported that this was not at all true (students without disability: 3.9%).14

Furthermore, 64.4 per cent of young people with disability said that it was very much true that there was a parent or another adult at home who believes they will achieve good things. This is slightly below the proportion of young people without disability stating the same (69.4%).

|

Young people with disability |

Young people without disability |

|

|

Very much true |

64.4 |

69.4 |

|

Pretty much true |

23.2 |

20.5 |

|

A little true |

10.8 |

7.8 |

|

Not at all true |

1.7 |

2.4 |

Source: Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables [unpublished]

Further data and research on the educational outcomes and experiences of WA children and young people with disability are needed.

Endnotes

- The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions… In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities.’ Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2018: Western Australia, Table 1.1 Persons with disability, by age and sex, estimate, and Table 1.3 Persons with disability, by age and sex, proportion of persons.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017, Disability in Australia: changes over time in inclusion and participation in education, Cat No DIS 69, AIHW.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, 4430.0 - Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: 2018, Table 7.1 and 7.3: Children aged 5-14 years with disability, living in households, Whether attends school, special school, or special classes by Sex and Severity of disability – 2018, ABS.

- Article 23, United Nations 1989, Convention on the Rights of the Child, United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner.

- Department of Education and Training, Disability Standards for Education 2005 Fact Sheet, Australian Government.

- Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability in Education Council, 2016 emergent data on students in Australian schools receiving adjustments for disability.

- Mitchell D 2010, Education that fits: Review of international trends in the education of students with special educational needs, July 2010, University of Canterbury.

- Douglas G et al 2012, Measuring Educational Engagement, Progress and Outcomes for Children with Special Educational Needs: A Review, Department of Disability, Inclusion and Special Needs (DISN), School of Education, University of Birmingham.

- The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) 2013, Inclusive Education for Students with Disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice, ARACY, p. 29.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey: The views of WA children and young people on their wellbeing - a summary report, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA.

- Education and Employment References Committee, 2016, Access to real learning: the impact of policy, funding and culture on students with disability, Australian Government.

- McCoy S et al 2016, The role of parental expectations in understanding social and academic well-being among children with disabilities in Ireland, European Journal of Special Needs Education, Vol 31, No 4.

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA 2020, Speaking Out Survey 2019 Data Tables, Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished].

Last updated June 2020

Supporting student engagement and academic achievement is important. There must be an ongoing commitment to improving the achievement of students at or below the national minimum standard. Policy and practice must focus on addressing the complex barriers that impede our most vulnerable children throughout their school years.1

Schools can employ several approaches to support students’ academic achievement and engagement in school. To encourage attendance and improve educational outcomes for all children and young people, schools need to ensure a welcoming, supportive and inclusive environment for students and their families. Targeted teaching that is tailored to each student’s capability and level is required to reduce the significant achievement gap that exists between high achieving and low achieving students. This will ensure high achieving students are stretched and low achieving students are supported.2 This aligns with the recommendations of David Gonski and colleagues in their 2018 review of student achievement and school performance.3

Students’ motivation and engagement improves when teachers and staff foster a school and classroom environment that supports both learning and emotional development. For more information, refer to the Commissioner for Children and Young People School and Learning Consultation: Technical Report.

Teachers and schools serving disadvantaged communities need appropriate resources to implement initiatives to help them build capacity. On the ground initiatives that support disadvantaged communities can include: attracting high-performing teachers and principals, instigating mentoring programs for teachers, employing a teacher with expertise in Aboriginal student learning outcomes, and increased monitoring of school performance.4

Parental engagement is also a key part of promoting and improving children’s learning capabilities and wellbeing. Refer to the Commissioner’s resource How can you help your child to be engaged in school and learning for more information for parents, carers and family.

Research suggests that a necessary component of improving educational and lifetime outcomes for disengaged students is to increase the accessibility of alternative pathways, such as vocational education and training.5,6 These pathways need to be diverse and flexible so that they attract and retain students. These programs do not work in isolation, coordinated support for disengaged students is also critical. Students will often have many support needs and will require a range of support systems, not just to learn, but also in the personal arena to support their wellbeing more broadly.7

For students in care, raising educational aspirations is critical. Research suggests that for young people in care having a specific end-goal of education in mind can assist students to feel a sense of purpose and connection with their school environment. This will provide students with a reason to invest time and effort in learning and achieving, and foster engagement.8

Data gaps

Robust data on the academic achievement of young people with disability is needed; without this, it is difficult to assess whether young people with disability are being provided with consistent and equitable access to education and support.

There is also no recent and publicly available data on the academic achievement of young people in care in WA. Young people in care are a highly vulnerable group and it is critical they have appropriate support and opportunities to achieve academically.

Endnotes

- Cassells R et al 2017, Educate Australia Fair?: Education Inequality in Australia, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, Focus on the States Series, Issue No 5.

- Goss P and Sonnemann J 2016, Widening gaps: What NAPLAN tells us about student progress, Grattan Institute.

- Gonski D et al 2018, Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, Commonwealth of Australia, p. x.

- Centre for International Research on Education Systems 2015, Low SES School Communities National Partnership: Evaluation of staffing, management and accountability initiatives, Victoria University, pp. 8-11.

- Hancock KJ and Zubrick SR 2015, Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school, prepared by Telethon Kids Institute for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 61

- Stone C 2012, Valuing Skills: Why Vocational Training Matters, Occasional Paper 24, Centre for Policy Development.

- Hancock KJ and Zubrick SR 2015, Children and young people at risk of disengagement from school, prepared by Telethon Kids Institute for the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA, p. 61.

- Tilbury C et al 2014, Making a connection: school engagement of young people in care, Child & Family Social Work, Vol 19.

For more information on educational achievement refer to the following resources:

- Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) 2018, Parent Engagement in communities with low socioeconomic status, ARACY.

- Cassells R et al 2017, Educate Australia Fair?: Education Inequality in Australia, Focus on the States Series, Issue No 5, Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre.

- Gonski D et al 2018, Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Goss P and Sonnemann J 2016, Widening gaps: What NAPLAN tells us about student progress, Grattan Institute.

- Jensen B 2010, Measuring what matters: student progress, Grattan Institute.

- Lamb S et al 2015, Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out, Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University for the Mitchell Institute.