Safe in the home

Feeling safe and being safe at home is critical for children’s healthy development. A safe and supportive family provides a sense of security which supports attachment, enables children to develop good mental health and responds appropriately to children’s needs.1,2

National and international research consistently refers to the profound impact family violence, abuse and neglect can have on children both in the short term and into adulthood. The consequences can include poor physical health, secure attachment problems, learning and developmental problems, substance abuse, mental health issues and homelessness.3

Last updated August 2020

Limited data is available on whether WA children aged 0 to 5 years feel, or are, safe at home.

Overview

This indicator considers some key measures on whether children feel safe and are safe at home. This includes data on family and domestic violence and the child protection system in WA.

No data exists on whether WA children aged 0 to five years feel safe at home.

Areas of concern

The lack of data on very young children’s feelings of safety at home.

In 2017, a child or young person was present at 12,726 recorded incidents of family and domestic violence across WA.

For over one-quarter (26.9%) of the WA children and young people who have had contact with the child protection system, the primary reason was neglect.

At 30 June 2019, the rate of WA Aboriginal children in out-of-home care was 64.1 per 1,000 children, 17 times the rate for WA non-Aboriginal children (3.8 per 1,000).

Infants are more likely to be subject to child protection substantiations than all other age groups, with 13.0 per 1,000 infants being subjects of substantiations of notifications compared to 8.8 per 1,000 children aged one to four years.

Other measures

Injuries and poisoning are major causes of hospitalisation for children in Australia. Although the overall risk is low, children aged from 0 to five years are at a higher risk than older age groups of death (in particular from sudden infant death syndrome or drownings) and injury and poisoning in the home.1 A measure on child deaths or injuries has not been selected for the Indicators of wellbeing as data is regularly compiled by Kidsafe WA and the WA Ombudsman.

For information on child deaths refer to the Ombudsman’s annual Child Death Review. For information on injuries for children refer to Kidsafe WA Childhood Injury Bulletins & Reports.

Endnotes

- Sherlock E et al 2018, Kidsafe WA Childhood Injury Bulletin: Annual Report 2017-2018, Kidsafe WA (AUS).

Last updated September 2019

Safe and supportive relationships in the home are essential for young children’s development. Feeling safe at home is critical for young children to develop secure attachment, good mental health and effectively participate in learning.1

Young children who feel unsafe at home often feel frightened, anxious and worried, which over time can result in trauma and toxic stress responses which can negatively impact brain development.2

There is no data available on whether WA children aged 0 to 5 years feel safe at home.

Children aged 0 to five years may not feel safe when there is family dysfunction including alcohol and drug use, family and domestic violence, parental mental health issues, harsh parenting or bullying. Parents experiencing high levels of stress or trauma may also be unable to provide their child with a sense of security, resulting in their child feeling unsafe and insecure.3

Older children and young people (aged 10 to 17 years) described safety in relation to being surrounded by others that they felt safe with, that they trusted and were reliable to be able to protect them from danger. Adults that were inconsistent, unpredictable and bullied or threatened were identified as unsafe.4

There is limited data or research on how very young children feel about safety in their home. This is in part because research with children of a young age includes the complexity of gaining informed consent from young children.5 It is also because gathering young children’s perspectives often requires creative data collection methods such as the use of photography, visual aids or role play, rather than survey questionnaires.6,7

Consultations and research with younger children are important and more work is required to develop research methodologies and instruments that appropriately capture the experiences of very young children.

Endnotes

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2009, Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships, Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, p. 1.

- Hunter C 2014, Effects of child abuse and neglect for children and adolescents, National Child Protection Clearinghouse Resource Sheet, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- McLean S 2016, Children’s attachment needs in the context of out-of-home care, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Moore T et al 2016, Our safety counts: Children and young people’s perceptions of safety and institutional responses to their safety concerns, Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, p. 7, 16.

- Dockett S et al 2009, Researching with children: Ethical tensions, Journal of Early Childhood Research, Vol 7, No 3.

- Ibid.

- Clark A et al 2003, Exploring the field of listening to and consulting with young children, Research Report 445, Thomas Coram Research Unit, Department for Education and Skills, p. 8, 30.

Last updated August 2020

Every child has a right to live free from violence, abuse and neglect.1 Most children live in safe and supportive homes, however for some, home can be a place of conflict and distress as a result of family and domestic violence.

There is considerable overlap between children being exposed to family and domestic violence and the child protection system. When a physical assault on a child is reported, the police officer in charge will make an assessment about whether to involve child protection authorities through a formal notification. The Department for Communities then determines whether the child has suffered significant harm or is likely to suffer significant harm as a result of exposure to family and domestic violence.2

The next measure (Involved in the child protection system) records child protection service responses, including notifications, substantiations and children in care.

Family and domestic violence can be defined as ‘abusive behaviour in an intimate relationship or other type of family relationship where one person assumes a position of power over another and causes fear’.3 Abusive behaviour can include physical abuse or verbal, mental or emotional abuse or control. For children it is often perpetrated by parents/carers, however, perpetrators can also be siblings and other family members such as step-fathers.

Living with family and domestic violence has short and long-term impacts on children’s health and wellbeing. These include mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, difficulties with learning, behavioural issues, a higher likelihood of future alcohol and drug misuse and greater risk of homelessness.4,5

Research also suggests that family and domestic violence can impact a parent’s ability to parent effectively.6

Data on children’s exposure to family and domestic violence is limited because it is often underestimated by parents and under-reported to the police for various reasons, including concerns that children will be removed by child protection workers.7

Children experiencing family and domestic violence as onlookers

Experiencing family and domestic violence involves children and young people not only being subject to family and domestic violence, but also witnessing family and domestic violence. Research has shown that the existence of violent behaviour in the home increases the likelihood of trauma and negative health and wellbeing outcomes.8,9,10 This can have effects on a child’s coping mechanisms and sense of self, can cause a state of hyper-vigilance and in some cases can manifest as post-traumatic stress disorder.11

The WA Police Force (WA Police) collect data on whether children are present at family violence-related incidents.12

Almost one-half of all family violence-related crime incidents reported, or becoming known to, WA Police between 2014 and 2017 had at least one child or young person present.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

|

Number of FV incidents |

21,641 |

26,913 |

31,316 |

28,716 |

|

Number of distinct FV incidents |

10,047 |

12,132 |

14,081 |

12,726 |

|

Proportion of incidents where |

46.4 |

45.1 |

45.0 |

44.3 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV incidents recorded in the Incident Management System (IMS) where at least one child was present, provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

* A child or young person aged 0 to 17 years.

Notes:

1. Crime incidents are recorded in the IMS where one or more valid offences are suspected to have occurred.

2. The family violence data is collected using the family violence (FV) flag in police systems. WA Police select the FV flag at the victim level when they have determined an offence or incident to be FV-related as defined by the relevant state legislation (Refer to ABS 0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 – Explanatory Notes for more information).

3. Reporting on family violence by WA Police changed from 1 July 2017 due to changes in the legislation, for more information refer to: The Restraining Orders and Other Legislation Amendment (Family Violence) Bill 2016.

In 2017, a child or young person (aged 0 to 17 years) was present at 12,726 recorded crime incidents of family violence across WA.

In the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey, 68 per cent of Australian women and 60 per cent of Australian men who had children in their care when they experienced intimate partner violence reported that the children had seen or heard the violence.13

The proportion of family violence-related crime incidents where a child was present varies between WA regions and districts, with the Wheatbelt and South West districts having the highest proportions followed by the Metropolitan region.

|

Total incidents |

Total incidents |

Proportion of incidents |

|

|

Central Metropolitan |

4,018 |

1,746 |

43.5 |

|

North West Metropolitan |

4,249 |

2,064 |

48.6 |

|

South East Metropolitan |

4,539 |

2,162 |

47.6 |

|

South Metropolitan |

5,061 |

2,506 |

49.5 |

|

Metropolitan region |

17,867 |

8,478 |

47.5 |

|

Goldfields-Esperance |

1,254 |

469 |

37.4 |

|

Great Southern |

891 |

388 |

43.5 |

|

Kimberley |

3,427 |

1,017 |

29.7 |

|

Mid West-Gascoyne |

1,615 |

750 |

46.4 |

|

Pilbara |

1,720 |

643 |

37.4 |

|

South West |

1,336 |

667 |

49.9 |

|

Wheatbelt |

606 |

314 |

51.8 |

|

Regional total |

10,849 |

4,248 |

39.2 |

|

Total incidents |

28,716 |

12,726 |

44.3 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV crime incidents reported to WA Police, provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

Note: District is based on the location of the offence.

It should be noted that this data is the raw numbers of incidents without the commensurate population and therefore does not provide the rates of occurrence by area.

Children experiencing family and domestic violence as direct victims

In 2017, 562 crime incidents14 (2.1% of all crime incidents) were reported to WA Police where WA children less than nine years of age were one of the victims of family violence.

|

Number |

Per cent of total |

|

|

0 to 9 years |

562 |

2.1 |

|

10 to 17 years |

1,674 |

6.3 |

|

18 to 24 years |

4,395 |

16.5 |

|

25 to 44 years |

15,186 |

56.9 |

|

45 to 64 years |

5,709 |

21.4 |

|

65+ years |

766 |

2.9 |

Source: WA Police custom report of FV crime incidents recorded in the Incident Management System (IMS), provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA

Note: Values are a distinct count/ distinct per cent of incidents by demographics and offence location. As an incident may have multiple victims recorded across all demographics, the figures should not be summed.

It should be noted that WA Police are only able to record incidents detected and/or reported to them. There is clear evidence that family violence incidents are under-reported.15

In 2016, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) asked adult survey respondents to the Personal Safety Survey about experiences of childhood abuse. According to this survey, 13.0 per cent (2.5 million) of Australian adults have experienced childhood abuse (either physical, sexual or both). The majority of people experienced only one type of abuse; 5.8 per cent of respondents experienced physical abuse, 5.0 per cent experienced sexual abuse and 2.7 per cent experienced both.16

Based on this survey, an estimated one in 12 children and young people experienced physical abuse and one in 13 experienced sexual abuse before 15 years of age. Most adults who reported they were abused as children experienced their first incident before the age of 10.17

An estimated 81.0 per cent of people who experienced childhood physical abuse were first abused by a family member (78.0% were first abused by a parent). While, an estimated 51.0 per cent of people who experienced childhood sexual abuse were first abused by a non-familial known person (35.6% were abused by a family member).18

Analysis by the ABS showed that 71.0 per cent of people who experienced abuse as a child also experienced violence as an adult, compared to 33.0 per cent of those who did not experience childhood abuse.19

The ABS annually reports data on victims of family and domestic violence through the Recorded Crimes – Victims collection gathered from police agencies within each Australian jurisdiction.20

In 2019, 493 WA children aged between 0 and nine years were reported as victims of physical and sexual assault as a result of family and domestic violence.

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

Per cent change since 2014 |

||

|

0 to 9 years* |

Physical assault |

218 |

274 |

314 |

342 |

342 |

351 |

61.8 |

|

Sexual assault |

140 |

126 |

139 |

192 |

134 |

142 |

- |

|

|

Total |

359 |

400 |

451 |

536 |

476 |

493 |

37.3 |

|

|

10 to 14 years* |

Physical assault |

383 |

469 |

559 |

538 |

531 |

556 |

45.2 |

|

Sexual assault |

130 |

89 |

113 |

152 |

140 |

168 |

29.2 |

|

|

Total |

513 |

558 |

670 |

690 |

671 |

724 |

41.1 |

|

|

15 to 19 years* |

Physical assault |

1,380 |

1,619 |

1,767 |

1,492 |

1,529 |

1,658 |

20.1 |

|

Sexual assault |

108 |

106 |

104 |

100 |

148 |

135 |

25.0 |

|

|

Total |

1,488 |

1,725 |

1,867 |

1,591 |

1,677 |

1,793 |

20.5 |

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 and 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault/sexual assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014-2019

* The age groupings are not equal – 0 to 9 years reports on 10 years, 10 to 14 years reports on 5 years and 15 to 19 years reports on 4 years.

Note: This data differs from the previous table as it includes only physical and sexual assault, compared to all incidents categorised as family and domestic violence.

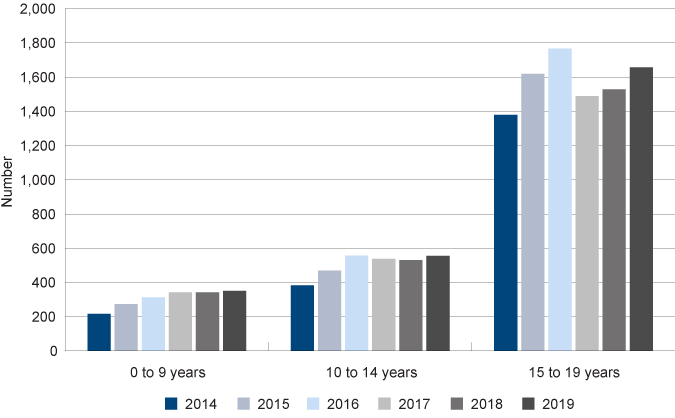

Victims of family and domestic violence physical assault by age group, number, WA, 2014 to 2019

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014-2019

For WA children aged 0 to nine years, there has been a 61.8 per cent increase in the number of children reported as victims of physical assault due to family and domestic violence between 2014 and 2019.

There was no change in the number of WA children aged 0 to nine years reported as victims of family and domestic violence sexual assault from 140 in 2014 to 142 in 2019.

For WA children aged 0 to nine years, there has been a 61.8 per cent increase in the number of children reported as victims of physical assault due to family and domestic violence between 2014 and 2019.

There was no change in the number of WA children aged 0 to nine years reported as victims of family and domestic violence sexual assault from 140 in 2014 to 142 in 2019.

It is not known whether these changes represent a change in the rate of occurrence or the impact of other factors, including population change or varying rates of reporting to WA Police. It should be noted that sexual assault is much less likely to be reported to the police for multiple reasons including the victim feeling shame, stigma, concern about whether they will be believed and sometimes fear of the perpetrator.21

If a sexual assault is reported for a child or young person under 18 years of age, the police officer in charge must report this to the Department of Communities under the mandatory reporting regime.22

|

Physical assault |

Sexual assault |

|||||

|

0 to 9 years |

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

0 to 9 years |

10 to 14 years |

15 to 19 years |

|

|

Male |

186 |

252 |

365 |

43 |

32 |

12 |

|

Female |

146 |

293 |

1,282 |

98 |

132 |

122 |

|

Total |

351 |

556 |

1,658 |

142 |

168 |

135 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 24 and 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related assault, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014–2019

* The total includes victims whose sex was not specified.

A higher number of male children (aged 0 to nine years) are physically assaulted than female children, while a greater number of female children in this age group are sexually assaulted than male children.

Data from the ABS Personal Safety Survey shows that parents are the most common perpetrators of physical abuse of children younger than 15 years. Respondents to the survey were asked whether they experienced abuse before the age of 15 years. Of those who were victims of abuse before the age of 15 years, around 42.0 per cent were victims of physical abuse by a father or stepfather, and 22.0 per cent by a mother or stepmother.23 Approximately six per cent were abused by a sibling (which can include an adult sibling).24 A significant proportion were also abused by another ‘known person’.

Research indicates that women in regional, rural and remote areas are more likely to be victims of family and domestic violence.25,26 Across Australia, 23.0 per cent of women living outside major cities reported experiencing partner violence compared with 15.0 per cent living in major cities.27 There is no comparable research on the experiences of children and young people in regional and remote locations.

The cultural and social characteristics of rural and remote communities can influence the prevalence of family and domestic violence. Some of these factors include more traditional gender norms, a lack of access to appropriate services due to greater isolation, and for some communities, there is a greater focus on privacy and self-reliance.28

Data from the ABS 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) shows that there is a higher rate of family and domestic violence in Aboriginal families than non-Aboriginal families across Australia.29 This should be understood in the context of a history of colonisation, forced child removal, social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma.30

Aboriginal Australians are also more likely to have increased risk factors for family violence such as poor and overcrowded housing, higher levels of poverty, lower education and higher unemployment.31

The ABS collection on Recorded Crime – Victims does not report on data for Aboriginal peoples in WA as the data is not of sufficient quality.32 Furthermore, the NATSISS survey does not provide jurisdictional level data nor data on children and young people’s experiences of family and domestic violence.33

In the Longitudinal Study of Aboriginal Children, participating families were asked about family violence, and families living in remote areas were significantly more likely to rate family violence as a big problem in the community.34

There is no data available on children’s exposure to family and domestic violence in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, although research suggests that women in CALD communities are particularly vulnerable to experiencing family and domestic violence.35,36

There are many barriers that prevent CALD families from reporting violence and accessing services or support, including language difficulties, cultural differences regarding asking for help, and isolation due to separation from other family and friends.37

Considering their high risk of exposure, the lack of data and research with Aboriginal and CALD children experiencing family and domestic violence is a significant gap.

Family violence-related homicide

In a small but critical number of cases family and domestic violence results in the tragic death of the victim or victims. Relative to other Australian jurisdictions, a high number of WA people were murdered in a family and domestic violence incident in 2016 and 2018, however there were significantly fewer deaths in 2019.

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

NSW |

42 |

30 |

35 |

38 |

|

VIC |

37 |

35 |

31 |

36 |

|

QLD |

34 |

24 |

22 |

20 |

|

SA |

19 |

19 |

10 |

14 |

|

WA |

35 |

16 |

35 |

12 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2019, Table 23 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related homicide, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014-2019

Furthermore, in 2019, no WA children and young people (aged 0 to 19 years) lost their lives due to family and domestic violence-related homicide (compared to 13 children and young people in 2018).38

From 30 June 2009 to 30 June 2019, family and domestic violence was the leading social and environmental factor that was associated with 72.0 per cent of investigable39 child deaths in WA.40

Across Australia, around 10.0 per cent of Australian homicide victims are children and young people aged 0 to 17 years. The majority are victims of filicide (murdered by their parents).41

Children under five years of age are at particular risk of filicide. During 2000–01 to 2011–12 approximately 69.0 per cent of children and young people who were filicide victims across Australia were under five years of age.42 Data suggests that young children are murdered in relatively equal proportions by mothers and fathers (including step-fathers).43

Endnotes

- Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [website].

- Child abuse includes emotional abuse where young people are exposed to family and domestic violence as onlookers and they are deemed at risk of significant emotional/mental harm. When a physical assault on a child or young person is reported, the officer in charge will make an assessment about whether to involve child protection authorities. The Department for Communities then determines whether a child has suffered significant harm or is likely to suffer significant harm as a result of exposure to family and domestic violence. Significant harm or likelihood of significant harm may be caused by a single act of family and domestic violence or the cumulative impact of exposure over a period of time. Source: WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support (now Communities) 2014, Emotional abuse – Family and domestic violence policy, WA Government. If a sexual assault is reported for a child or young person under 18 years of age, the police officer in charge must report this to the Department of Communities under the mandatory reporting regime.

- QLD Department of Child Safety 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection – practice paper, QLD Government, p. 3.

- Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: CFCA Paper No. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 6

- Richards K 2011, Children’s exposure to domestic violence in Australia, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, No 419, Australian Institute of Criminology, p. 3.

- Kaspiew R et al 2017, Domestic and family violence and parenting: Mixed method insights into impact and support needs: Final report, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013, Defining the Data Challenge for Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence, ABS.

- Campo M 2015, Children’s exposure to domestic and family violence: CFCA Paper No. 36, Australian Institute of Family Studies, p. 6.

- Richards K 2011, Children’s exposure to domestic violence in Australia, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, No 419, Australian Institute of Criminology, p.1.

- QLD Department of Child Safety 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection – practice paper, QLD Government, p. 12-13.

- Taylor A 2019, Impact of the experience of domestic and family violence on children – what does the literature have to say?, Queensland Centre for Domestic and Family Violence Research.

- In line with the amendments made to the Restraining Orders Act 1997 (ROA) on 1 July 2017, the terminology used by the WA Police Force is ‘family violence’. The term domestic violence is no longer used within the policing context.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, Cat no FDV 3, AIHW, p. 71.

- Crime incidents of family violence are incidents that include a valid offence.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013, Defining the Data Challenge for Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, Table 43.3 Experience of either physical or sexual abuse before the age of 15(a), ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, Media Release: Childhood abuse increases risk of violence in adulthood, ABS.

- [1] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 Explanatory Notes, ABS.

- Australian Law Reform Commission 2010, The prevalence of sexual violence, Australian Government [website].

- WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support (now Communities) 2014, Policy on child sexual abuse, WA Government.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016, Table 31.3 Experience of abuse before the age of 15, Characteristics of abuse by sex of respondent, Proportion of persons, ABS.

- Ibid.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Mishra G et al 2014, Health and wellbeing of women aged 18 to 23 in 2013 and 1996: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, Report prepared for the Australian Government, Department of Health.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, Cat no FDV 3, AIHW, p. 101.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018, Cat No FDV 2, AIHW, p. 85.

- Campo M and Tayton S 2015, Domestic and family violence in regional, rural and remote communities: An overview of key issues, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2018, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018, Cat no FDV 2, AIHW, p. 88.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2018 Explanatory Notes, ABS.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, 4714.0 - National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–15, ABS.

- Bennetts Kneebone L 2015, Partner violence in the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), Research summary: No.3/2015, Department of Social Services, p. 9.

- Campo M 2015, Children's exposure to domestic and family violence: Key issues and responses, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- El Murr A 2018, Intimate partner violence in Australian refugee communities, Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Queensland Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women 2018, Domestic and family violence and its relationship to child protection: a practice paper, QLD Government, p. 19.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2020, Victims of FDV related offences, Table 25 Victims of Family and Domestic violence-related homicide, Selected characteristics, Selected states and territories, 2014-2019.

- The WA Ombudsman Child Death Review considers reportable deaths of WA children and young people aged 0 to 17 years. Investigable deaths are defined in the Ombudsman’s legislation, the Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1971 (see Section 19A(3)).

- WA Ombudsman 2019, Annual Report 2018-19: Child Death Review, WA Government, p. 66.

- Brown T et al 2019, Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice – Filicide Offenders, Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Last updated August 2020

Although the majority of WA children are living in a safe and supportive home environment, some children are unable to live with their families for a range of reasons including abuse or neglect.1

The child protection system provides assistance to vulnerable children and young people who are suspected of being abused, harmed or neglected.2 In WA, the Department of Communities is responsible for child protection and investigates, responds to and manages child protection cases.

Forms of child abuse and neglect are generally categorised as physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect.3 Emotional abuse includes children witnessing incidents of family and domestic violence when it is determined by the Department of Communities that the child or young person is at risk of significant harm.4 For information on family and domestic violence refer to the measure: Experiencing family and domestic violence.

This measure reports on data on WA children and young people involved in the child protection system. Most of the available data provides information about the number of children and young people involved in child protection and the provision of child protection services.There is very limited data on the health and wellbeing of children who have contact with the WA child protection system despite them being a particularly vulnerable group.

Abuse and neglect can have a profound impact on children both in the short term and into adulthood including poor physical health, learning and developmental problems, substance abuse, mental illness, unlawful behaviour, homelessness and suicide.5

Recent research using linked data from WA has found that compared to children who have never had contact with the child protection system, children and young people who have left care are nearly twice as likely to be admitted to hospital, are three times more likely to have mental health-related issues, are less likely to complete high school and more likely to have contact with the juvenile justice system.6

Children receiving child protection services include those who are subject of an investigation of a notification; on a care and protection order; or living in care.7

Child protection data only include those cases of abuse and neglect that were detected and reported. However, child abuse and neglect often remain undetected for a variety of reasons including the private nature of the crime, the challenges children experience about whether to make disclosures and whether they will be believed if they choose to disclose, and the difficulty of gathering evidence to substantiate allegations.8 The data below is therefore likely to be an underestimation of the number of children being abused or neglected in WA.9

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) publishes the Child Protection Australia report on an annual basis. This report compiles data from state and territory child protection agencies.10

In 2018-19, all Australian states and territories adopted a national definition of out-of-home care which resulted in changes to the measurement in some jurisdictions. WA was already reporting data in a manner consistent with the new definition, therefore these changes have no impact on the WA data. However, data from some other jurisdictions may not match data previously published and should not be compared with data prior to 2018–19.11 Where relevant this will be noted in the tables and graphs below.

Most data on children in the child protection system is not disaggregated by age groups. Therefore, the analysis in this section is generally not specific to children aged 0 to five years.

Children and young people in the child protection system

At 30 June 2019, the Department of Communities reported 5,379 children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in care in WA.12 Of these, 205 were less than one year of age and 1,136 were between one and four years of age.

|

30 June 2017 |

30 June 2018 |

30 June 2019 |

|

|

Less than 1 year |

153 |

195 |

205 |

|

1 to 4 years |

1,038 |

1,034 |

1,136 |

|

5 to 9 years |

1,552 |

1,560 |

1,618 |

|

10 to 14 years |

1,432 |

1,548 |

1,664 |

|

15 years and older* |

620 |

692 |

756 |

|

Total |

4,795 |

5,029 |

5,379 |

Source: WA Department of Communities, Annual Reports

* Includes a small number of young people who are 18 years and older and are still under the care of the WA Government.

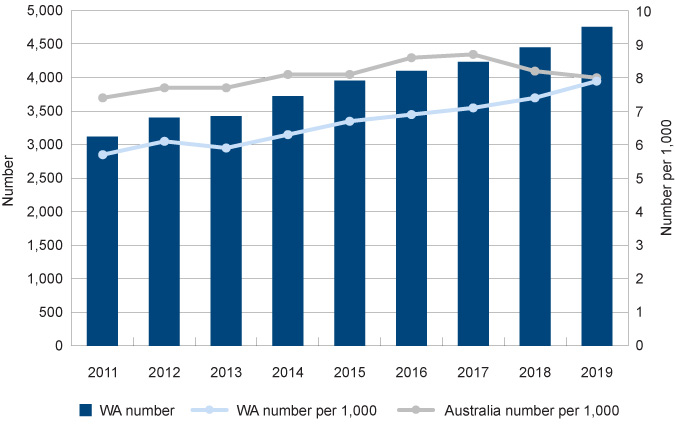

The rate of children and young people aged 0 to 17 years being in care in WA (at 30 June) has increased from 5.7 per 1,000 children and young people in 2011 to 7.9 per 1,000 in 2019.

|

WA* |

Australia |

|||

|

Number |

Number |

Number |

Number |

|

|

2011 |

3,120 |

5.7 |

37,648 |

7.4 |

|

2012 |

3,400 |

6.1 |

39,621 |

7.7 |

|

2013 |

3,425 |

5.9 |

40,549 |

7.7 |

|

2014 |

3,723 |

6.3 |

43,009 |

8.1 |

|

2015 |

3,954 |

6.7 |

43,399 |

8.1 |

|

2016 |

4,100 |

6.9 |

46,448 |

8.6 |

|

2017 |

4,232 |

7.1 |

47,915 |

8.7 |

|

2018 |

4,448 |

7.4 |

45,756 |

8.2 |

|

2019 |

4,754 |

7.9 |

44,906** |

8.0** |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Reports 2018–19, Table 5.2: Children in out-of-home care, by state or territory, 30 June 2019 (and previous years' reports)

* The AIHW reported number of children in care differs from the Department of Communities Annual Report as the Department of Communities includes unfunded living arrangements (including unendorsed arrangements). These are not included by AIHW to ensure national consistency. Refer AIHW, Child Protection Australia 2018–19 Appendixes B to G for further discussion of policy and practice differences that impact national comparability.

** The Australian total in 2018–19 is based on the new national definition of out-of-home care that excludes children on third-party parental responsibility orders. AIHW report that under the previous state-based definitions the 2018–19 total would have been 46,972 (an increase on the previous year).13

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in care, number and rate, WA and Australia, 30 June 2011 to 30 June 2019

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Reports 2018–19, Table 5.2: Children in out-of-home care, by state or territory, 30 June 2019 (and previous years' reports)

Notes:

1. The Australian rate in 2018–19 is based on the new national definition of out-of-home care that excludes children on third-party parental responsibility orders.14

2. The reduction in the number and rate of children in care across Australia in 2017–18 was principally due to a change in reporting practices in Victoria.

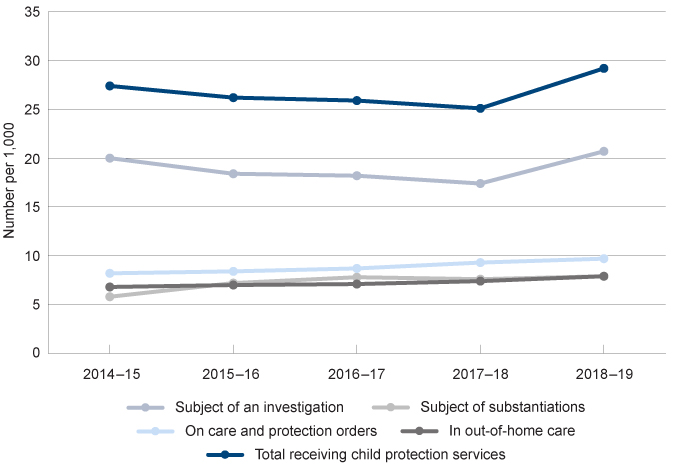

The rate of WA children and young people being subject to substantiations,15 on care and protection orders16 and in care has steadily increased in WA over the last five years, while the rate of investigations17 was decreasing until 2018–19 when it increased substantially (from 17.4 per 1,000 to 20.7 per 1,000 children and young people). In 2018–19, there was an overall increase in the rate of children and young people receiving all types of child protection services.

|

Subject |

Subject of |

On care and |

In care* |

Total receiving |

|

|

2014–15 |

20.0 |

5.7 |

8.1 |

6.7 |

27.0 |

|

2015–16 |

18.4 |

7.1 |

8.3 |

6.9 |

25.8 |

|

2016–17 |

18.2 |

7.8 |

8.7 |

7.1 |

25.9 |

|

2017–18 |

17.4 |

7.6 |

9.3 |

7.4 |

25.1 |

|

2018–19 |

20.7 |

7.9 |

9.7 |

7.9 |

29.2 |

Source: AIHW Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table A1: Children in the child protection system, by state or territory, 2014–15 to 2018–19 and Table 2.2 Children receiving child protection services, by state or territory, 2018–19 (and previous years' equivalents).

* On care and protection orders and in care are at 30 June in relevant year. The remainder are during the year.

Notes:

1. Children might be involved in more than one component of the child protection system. As such, the components do not sum to the total children receiving child protection service.

2. WA in care data exclude children on third-party parental responsibility orders and from 2015–16 includes children placed in boarding schools.

3. Total receiving child protection services includes children who are subject of a notification under investigation.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in the child protection system, number per 1,000, WA, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table A1: Children in the child protection system, by state or territory, 2014–15 to 2018–19 and Table 2.2 Children receiving child protection services, by state or territory, 2018–19 (and previous years equivalents)

The significant increase in 2018–19 in the number of children and young people subject to investigations per 1,000 children and young people is related to an increase in the number of notifications received from 18,168 in 2017–18 to 20,700 and a corresponding increase in the number of investigations of notifications from 12,154 in 2017–18 to 14,200 in 2018–19.18

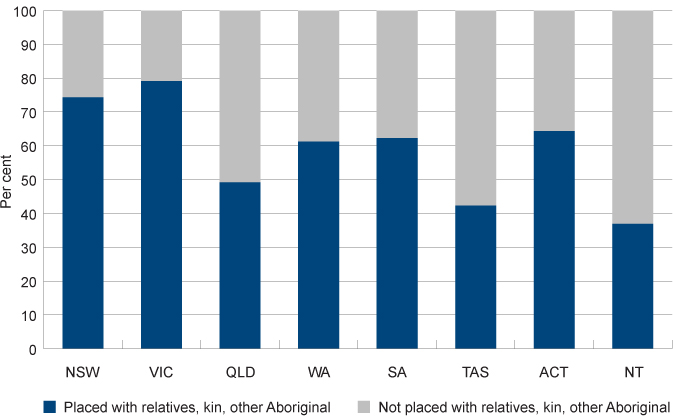

Aboriginal children and young people

WA Aboriginal children and young people are significantly overrepresented in the child protection system in comparison to non-Aboriginal children and young people.

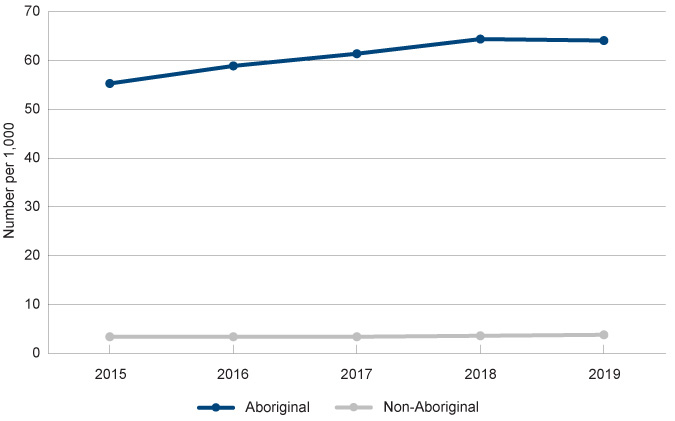

At 30 June 2019, the rate of WA Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care was 64.1 per 1,000 children, 17 times the rate for WA non-Aboriginal children and young people (3.8 per 1,000).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

Number |

Rate |

|

|

2015 |

2,062 |

55.3 |

1,890 |

3.4 |

3,954 |

6.7 |

|

2016 |

2,212 |

58.9 |

1,887 |

3.4 |

4,100 |

6.9 |

|

2017 |

2,321 |

61.4 |

1,911 |

3.4 |

4,232 |

7.1 |

|

2018 |

2,452 |

64.4 |

1,994 |

3.6 |

4,448 |

7.4 |

|

2019 |

2,604 |

64.1 |

2,148 |

3.8 |

4,754 |

7.9 |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Child protection Australia: 2018–19, Table S5.10: Children in out-of-home care, by Indigenous status and state or territory, 30 June 2019, AIHW and previous years' tables.

The rate of Aboriginal children and young people being in care across WA increased substantially from 2011 to 2018 but decreased marginally in 2019. In contrast the rate of non-Aboriginal children and young people being in care has remained relatively static.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in care by Aboriginal status, number per 1,000, Australia, 30 June 2015 to 2019

Source: AIHW, Child protection Australia: 2018–19, Table S5.10: Children in out-of-home care, by Indigenous status and state or territory, 30 June 2019, AIHW and previous years' tables.

The overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people in the child protection system is influenced by persistent social disadvantage which began with the process of colonisation including policies of wage-theft, assimilation and forced child removals and has continued with ongoing discrimination, poverty and inter-generational trauma.19,20

There is also recognition that child protection systems around Australia may themselves contribute to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children and young people for various reasons. These include that when children are removed from their remote communities it is difficult to move toward family re-unification, western cultural bias regarding appropriate family practices, primary caregivers who are not biological parents being excluded from child protection proceedings, services provided not being culturally safe and child protection workers without the cultural knowledge to effectively support Aboriginal families.21,22,23,24

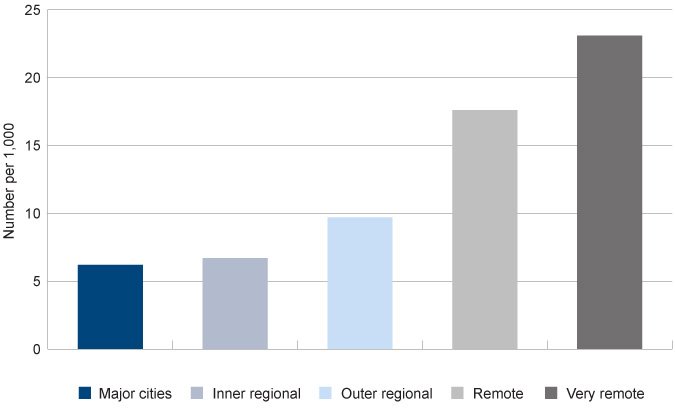

Children and young people living in remote and very remote locations in WA are three to four times more likely to be involved in the child protection system than children living in the metropolitan area. In WA, Aboriginal children and young people are more likely than non-Aboriginal children to live in remote and regional areas.

|

VIC |

QLD |

WA |

SA |

TAS |

ACT |

NT |

Australia |

|

|

Major cities |

11.8 |

3.8 |

6.2 |

3.5 |

N/A |

2.6 |

N/A |

7.4 |

|

Inner regional |

18.3 |

5.6 |

6.7 |

6.4 |

4.4 |

16.0 |

- |

10.6 |

|

Outer regional |

21.2 |

8.0 |

9.7 |

8.1 |

5.7 |

N/A |

10.0 |

10.1 |

|

Remote |

15.3 |

11.7 |

17.6 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

N/A |

30.9 |

16.2 |

|

Very remote |

N/A |

10.0 |

23.1 |

27.7 |

6.3 |

N/A |

26.8 |

20.1 |

|

Total |

13.4 |

4.9 |

7.4 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

2.6 |

18.3 |

8.6 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.7b: Children who were the subject of substantiations, by remoteness area and state or territory, 2018–19

N/A – the remoteness area classification is not valid for this jurisdiction.

Note: New South Wales did not provide data in 2018–19.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subject of substantiations by remoteness area, number per 1,000, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.7b: Children who were the subject of substantiations, by remoteness area and state or territory, 2018–19

For the 2018–19 year the WA Department of Communities Child Protection Activity Performance Information report provides further information on the children and young people in the WA child protection system.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent in district |

Number |

Per cent in district |

Number |

Per cent of total |

|

|

Metropolitan area |

||||||

|

Perth |

131 |

45.5 |

157 |

54.5 |

288 |

5.4 |

|

Armadale |

316 |

54.3 |

266 |

45.7 |

582 |

10.8 |

|

Cannington |

249 |

56.1 |

195 |

43.9 |

444 |

8.3 |

|

Fremantle |

180 |

53.3 |

158 |

46.7 |

338 |

6.3 |

|

Joondalup |

121 |

34.2 |

233 |

65.8 |

354 |

6.6 |

|

Midland |

239 |

49.7 |

242 |

50.3 |

481 |

8.9 |

|

Rockingham |

108 |

29.8 |

255 |

70.2 |

363 |

6.7 |

|

Mirrabooka |

171 |

48.9 |

179 |

51.1 |

350 |

6.5 |

|

Fostering/Adoption |

0 |

0.0 |

11 |

100.0 |

11 |

0.2 |

|

Regional and remote |

||||||

|

Goldfields |

121 |

79.1 |

32 |

20.9 |

153 |

2.8 |

|

Great Southern |

107 |

54.6 |

89 |

45.4 |

196 |

3.6 |

|

Mid West |

210 |

85.0 |

37 |

15.0 |

247 |

4.6 |

|

Peel |

94 |

29.0 |

230 |

71.0 |

324 |

6.0 |

|

Pilbara |

199 |

93.4 |

14 |

6.6 |

213 |

4.0 |

|

South West |

152 |

40.0 |

228 |

60.0 |

380 |

7.1 |

|

West Kimberley |

206 |

99.0 |

2 |

1.0 |

208 |

3.9 |

|

East Kimberley |

159 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

159 |

3.0 |

|

Wheatbelt |

179 |

62.2 |

109 |

37.8 |

288 |

5.4 |

|

Total |

2,942 |

54.7 |

2,437 |

45.3 |

5,379 |

100.0 |

Source: Department of Communities, Activity Performance Information: 2018-19, Children and young people in care at 30 June 2019, by district

* The Department of Communities number of children in care at 30 June differs from the AIHW Child Protection report as it includes unfunded living arrangements (including unendorsed arrangements). These are not included by AIHW to ensure national consistency.

Note: The district is generally where the family of the child resides at the time of the notification, however if a child is in care for a long period of time the district could be changed to where the child now resides.

In the Perth metropolitan area, a high proportion of children and young people in care were from Armadale (10.8% or 582), Midland (8.9% or 481) and Cannington (8.3% or 444). In certain regional and remote districts the number of Aboriginal children and young people in care compared to non-Aboriginal children was very high, in particular East Kimberley (100.0%), West Kimberley (99.0%), Pilbara (93.4%), Mid West (85.0%) and the Goldfields (79.1%).

It should be noted that this data does not take into account the number of children and young people living in the district.

This data highlights particular districts in WA where families and communities may require more accessible, relevant and culturally appropriate services and resources to assist them to provide a safe home for their children.

The high number of substantiated child abuse and neglect cases in regional and remote areas of WA is consistent with the greater prevalence of socioeconomic disadvantage in these regions, including homelessness and overcrowding, higher unemployment, and less access to services. In research into social exclusion in Australia, the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) determined that 36.0 per cent of Australian children in remote and very remote areas were facing the highest risk of social exclusion.25

For more information on social exclusion refer to the Material basics indicator.

Type of abuse

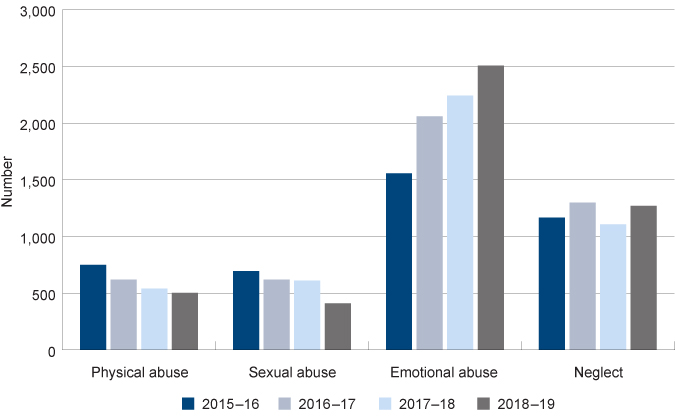

In 2018–19, emotional abuse is the most common primary type26 of abuse or neglect substantiated for WA children and young people (53.2%), followed by neglect (26.9%), physical abuse (10.7%), and sexual abuse (8.7%) in 2018–19.27

In 2015–16 the definition of emotional abuse in WA was broadened to include children and young people witnessing family and domestic violence. Since that time the number of children subject to substantiations related to emotional abuse have increased considerably (from 1,558 in 2015–16 to 2,508 in 2018–19). Over the same period, the number of children with substantiations where the primary type of abuse was physical or sexual abuse has decreased. Substantiations of neglect have remained relatively stable. Overall, while there have been shifts between categories, there has been a general increase in the number of children being subject to substantiations of abuse or neglect since 2015–16.

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

||

|

Number |

Per cent |

||||

|

Physical |

750 |

620 |

540 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual |

696 |

620 |

611 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional |

1,558 |

2,059 |

2,242 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

1,168 |

1,299 |

1,107 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

26 |

35 |

30 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

4,198 |

4,633 |

4,530 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years' equivalents)

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications by type of abuse or neglect, number, WA, 2015–16 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years' equivalents)

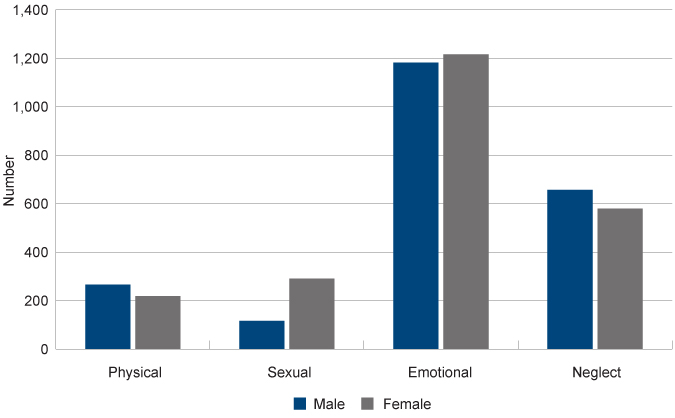

The type of abuse or neglect experienced is generally similar for male and female children and young people, with the exception that female children and young people are more likely than male children and young people to be the subjects of substantiations of sexual abuse.

|

Male |

Female |

Total* |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Physical |

266 |

11.9 |

218 |

9.4 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual |

116 |

5.2 |

290 |

12.5 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional** |

1,182 |

53.0 |

1,216 |

52.6 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

657 |

29.4 |

579 |

25.1 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

11 |

0.5 |

8 |

0.3 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

2,052 |

100.0 |

2,311 |

100.0 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.5: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19 by type of abuse or neglect, sex and state or territory

* Includes gender not stated.

** Emotional abuse includes children and young people witnessing family and domestic violence.

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications by type of abuse or neglect and gender, number, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.5: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19 by type of abuse or neglect, sex and state or territory

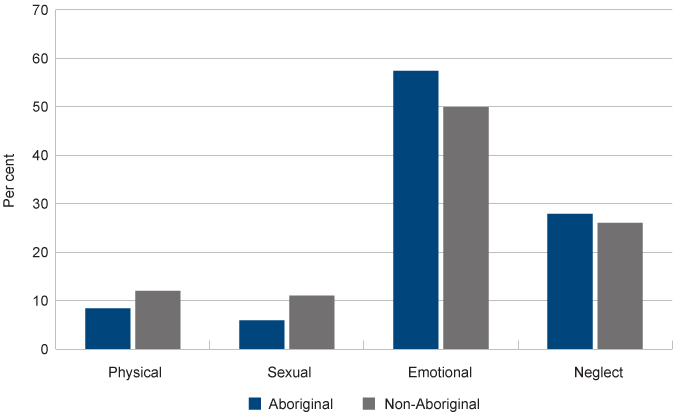

Emotional abuse (including family and domestic violence) was the most common type of substantiated abuse for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children and young people (Aboriginal: 57.4%, non-Aboriginal: 49.8%).

A lower proportion of Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal children and young people were subjects of substantiations of physical and sexual abuse (physical: 8.4% compared to 12.5%, sexual: 5.9% compared to 11.0%).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Physical |

178 |

8.4 |

325 |

12.5 |

503 |

10.7 |

|

Sexual |

125 |

5.9 |

287 |

11.0 |

412 |

8.7 |

|

Emotional |

1,211 |

57.4 |

1,297 |

49.8 |

2,508 |

53.2 |

|

Neglect |

590 |

27.9 |

681 |

26.1 |

1,271 |

26.9 |

|

Not stated |

7 |

0.3 |

16 |

0.6 |

23 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

2,111 |

100.0 |

2,606 |

100.0 |

4,717 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years' equivalents)

Children and young people aged 0 to 17 years who were subjects of substantiations of notifications by Aboriginal status and type of abuse or neglect, per cent, WA, 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.10: Children who were the subject of a substantiation of a notification received during 2018–19, by type of abuse or neglect, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years' equivalents)

A high proportion (26.9%) of WA children and young people who have had contact with the child protection system was as a result of neglect.

Neglect is a failure to provide minimally acceptable care.28 Research has highlighted strong and consistent relationships between child abuse and neglect and economic disadvantage.29 Neglect is closely associated with families experiencing poverty and social exclusion, although not all carers in poverty are neglectful and not all children who are neglected come from financially disadvantaged families.30 Across Australia, children and young people who are living in the lowest socioeconomic areas are more likely to be subject to a child protection substantiation than children living in other more advantaged areas (34.7% were in the areas with the lowest socioeconomic status compared to 6.3% in the highest).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

|

|

1 - Lowest |

41.8 |

31.6 |

34.7 |

|

2 |

28.4 |

23.0 |

24.3 |

|

3 |

14.7 |

23.8 |

21.3 |

|

4 |

11.4 |

14.3 |

13.4 |

|

5 - Highest |

3.6 |

7.2 |

6.3 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.8: Children who were the subjects of substantiations, by socioeconomic area and Indigenous status, 2018–19

In 2018–19, 41.8 per cent of Aboriginal children and young people who were subject to substantiations were living in the lowest socioeconomic areas of Australia (compared to 31.6% of non-Aboriginal children and young people).

A significantly higher proportion of Aboriginal families experience social and financial disadvantage, compared to non-Aboriginal families.31

Research using data from the 2016 Census concluded that in 2016, 31.4 per cent of Aboriginal Australians were living in poverty (50.0% median income before housing costs).32

Age of children and young people in the child protection system

In 2018–19, almost 6,000 (5,778) WA children aged under five years-old (and their families) were receiving child protection services.

The proportion of Aboriginal children receiving child protection services who were under five years of age was higher than the proportion of non-Aboriginal children (34.9% compared to 30.3%).

In particular, in 2018–19, the number of unborn Aboriginal children (i.e. prenatal mothers) who received child protection services is substantially higher than the number of non-Aboriginal unborn children (339 Aboriginal children compared to 233 non-Aboriginal children).

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total* |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Unborn |

339 |

N/A |

233 |

N/A |

671 |

N/A |

|

<1 years |

528 |

223.5 |

570 |

18.7 |

1,160 |

35.3 |

|

1 to 4 years |

1,717 |

187.0 |

2,033 |

15.6 |

3,947 |

28.4 |

|

5 to 9 years |

2,163 |

188.8 |

2,773 |

17.2 |

5,124 |

29.7 |

|

10 to 14 years |

1,981 |

177.0 |

2,750 |

18.0 |

4,864 |

29.6 |

|

15 to 17 years |

677 |

108.0 |

992 |

11.7 |

1,715 |

18.9 |

|

Total |

7,405 |

183.0 |

9,351 |

16.7 |

17,481 |

29.2 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S2.3 Children receiving child protection services, by age group, Indigenous status and state or territory, 2018–19

* Includes unknown Aboriginal status

N/A: Unborn children are covered under WA child protection legislation and are therefore included in the ‘All children’ rates. However, they are excluded in rate calculations for the ‘less than 1’ and ‘0–17’ categories. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Child welfare series No 72, Cat no CWS 74, AIHW, p. 24.

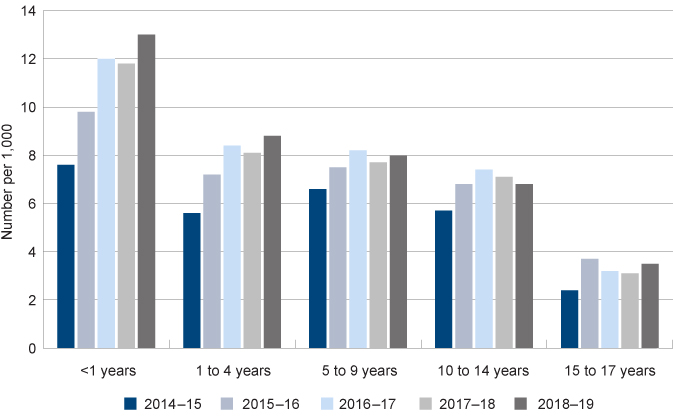

Data on substantiations by age group highlights that infants are significantly more likely to be subject to substantiations than other age groups, with 13.0 per 1,000 infants being subjects of substantiations of notifications, compared to 8.8 per 1,000 children aged one to four years.

From 2014–15 to 2018–19 there has been a substantial increase in the rate of infants (less than 1 year) being subject to substantiations of notifications (from 7.6 per 1,000 children in 2014–15 to 13.0 per 1,000 in 2018–19). It should be noted that the infant rate does not include unborn children, which have also increased over this time period.

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

<1 years |

7.6 |

9.8 |

12.0 |

11.8 |

13.0 |

|

1 to 4 years |

5.6 |

7.2 |

8.4 |

8.1 |

8.8 |

|

5 to 9 years |

6.6 |

7.5 |

8.2 |

7.7 |

8.0 |

|

10 to 14 years |

5.7 |

6.8 |

7.4 |

7.1 |

6.8 |

|

15 to 17 years |

2.4 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.5 |

|

0 to 17 years |

5.5 |

6.8 |

7.5 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

|

All children |

5.7 |

7.1 |

7.8 |

7.6 |

7.9 |

|

Children and young people |

3,382 |

4,198 |

4,633 |

4,530 |

4,717 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table 3.3: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications, by age group and state or territory, 2018–19 (rate) (and previous years’ reports)

Note: Unborn children are covered under WA child protection legislation and are therefore included in the ‘All children’ rates. However, they are excluded in rate calculations for the ‘less than 1’ and ‘0–17’ categories. Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2020, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Child welfare series No 72, Cat no CWS 74, AIHW, p. 24.

Children and young people who were subjects of substantiations of notifications, by age group, number per 1,000, WA, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19 Table 3.3: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications, by age group and state or territory, 2018–19 (rate) (and previous years’ reports)

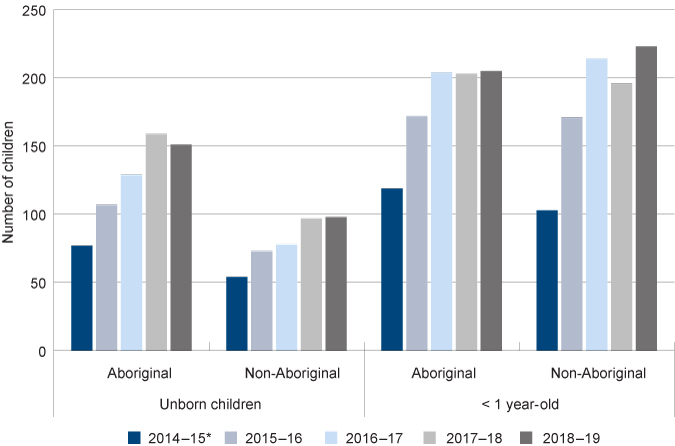

Over the last five years there has been a large increase in the number of unborn WA children being subject to a substantiation of a notification. In particular the number of Aboriginal unborn children subject to a substantiation of a notification increased significantly.

AIHW reports that 249 unborn WA children were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19. Of these, 60.6 per cent (151 children) were Aboriginal and 39.4 per cent (98 children) were non-Aboriginal children.33

|

2014–15* |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

||

|

Unborn children |

Aboriginal |

77 |

107 |

129 |

159 |

151 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

54 |

73 |

78 |

97 |

98 |

|

|

Total |

136 |

180 |

207 |

256 |

249 |

|

|

< 1 years old |

Aboriginal |

119 |

172 |

204 |

203 |

205 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

103 |

171 |

214 |

196 |

223 |

|

|

Total |

266 |

344 |

418 |

402 |

428 |

|

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.6: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19, by age group, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years’ equivalents)

* In year 2014–15 there were a number of children with unknown Aboriginal status (five unborn children and 44 < one year). They are included in the totals but not the Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal data.

Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during the year, by age group and Aboriginal status, number, WA, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S3.6: Children who were the subjects of substantiations of notifications received during 2018–19, by age group, Indigenous status and state or territory (and previous years’ equivalents)

* In year 2014–15 there were a number of children with unknown Aboriginal status (five unborn children and 44 < one year-old). They are included in the totals but not the Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal data. The data in the graph in 2014–15 is therefore understated.

South Australian research has shown that there are generally two groups of families that receive a notification for their unborn child:

- First time parents who had their own histories of abuse or neglect as children.

- Parents who had at least one child who was known to child protection.34

For both groups there were two key factors that were either reported to child protection or identified in the child protection histories of families: family and domestic violence and parental alcohol and other drug misuse.35

The disproportionate representation of unborn Aboriginal children in the child protection system is influenced by a history of colonisation, forced child removal, significant social and economic disadvantage and intergenerational trauma.36,37 These systemic factors impact Aboriginal peoples and increase their risk of experiencing family and domestic violence, alcohol and other drug misuse across multiple generations.38

When a notification is made for an unborn child in WA, processes are in place to do pre-birth planning, including intensive work with the mother and family to build support and divert the case away from child protection.39 However, an Australian study based in the Australian Capital Territory, found that only two-thirds of mothers whose unborn child had been notified were provided with some pre-natal support, and that women with more child protection reports were more likely to get this support, but also more likely to have their babies removed within 100 days of birth.40 To date there has been no WA research published on the implementation or effectiveness of the pre-birth planning process.

Recent WA-based research into infant removals found that Aboriginal infants had a higher risk of being removed from women with substance-use problems than non-Aboriginal infants. This research also found that greater proportions of Aboriginal infants were removed from remote, disadvantaged communities than non-Aboriginal infants.41

Considering the increasing rates of child protection involvement during pregnancy and the critical sensitivity of this issue, further WA research is essential and greater transparency of the process and outcomes is required.

Type of placement and placement stability

Most (87.0%) WA children and young people in care are in home-based care with either foster parents or a family member.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Foster care with family member (kinship) |

1,366 |

46.4 |

1,074 |

44.1 |

2,440 |

45.4 |

|

General foster care |

1,016 |

34.5 |

930 |

38.2 |

1,946 |

36.2 |

|

Parent/former guardian |

170 |

5.8 |

122 |

5.0 |

292 |

5.4 |

|

Residential care |

185 |

6.3 |

194 |

8.0 |

379 |

7.0 |

|

Unendorsed arrangement |

173 |

5.9 |

82 |

3.4 |

255 |

4.7 |

|

Other |

32 |

1.1 |

35 |

1.4 |

67 |

1.2 |

|

Total |

2,942 |

100.0 |

2,437 |

100.0 |

5,379 |

100.0 |

Source: Compiled from the Department of Communities, Activity Performance Information: 2018-19, Children and young people in care at 30 June 2019, by living arrangement

Only a small number of children in care (379 representing 7.0%) are in residential care or family group homes. Residential care is placement in a residential building where the purpose is to provide placements for children and where there are paid staff.42 The children and young people placed in residential care generally have more complex needs.43

Unendorsed arrangements are where a child self-selects to live with a person or people who have not been assessed or approved by the Department of Communities. In this instance the Department of Communities is required to arrange an assessment of the placement as a matter of urgency.44 It is important to note that Aboriginal children and young people are significantly over-represented in this category (67.8% of unendorsed arrangements are for Aboriginal children and young people).

Stable care placements tend to deliver better learning and psycho-social outcomes for affected children than those who experience ongoing episodes of instability.45 Placement instability can have significant adverse effects on children including attachment issues and a lack of safe and supportive relationships, which can lead to poor educational, socio-emotional and behavioural outcomes.46

Most (2,277) WA children and young people in care for more than two years have one placement, however 362 children and young people (11.7%) have had three or more placements.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

Total |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

1 |

1,280 |

72.9 |

997 |

73.6 |

2,277 |

73.2 |

|

2 |

255 |

14.5 |

216 |

15.9 |

471 |

15.1 |

|

3-4 |

163 |

9.3 |

110 |

8.1 |

273 |

8.8 |

|

5+ |

57 |

3.2 |

32 |

2.4 |

89 |

2.9 |

|

Total |

1,755 |

100.0 |

1,355 |

100.0 |

3,110 |

100.0 |

Source: AIHW, Child Protection Report 2018–19, Table S6.12: Children in out-of-home care for 2 or more years at 30 June 2019, by state or territory, Indigenous status, age and number of placements (Indicator 1.7b)

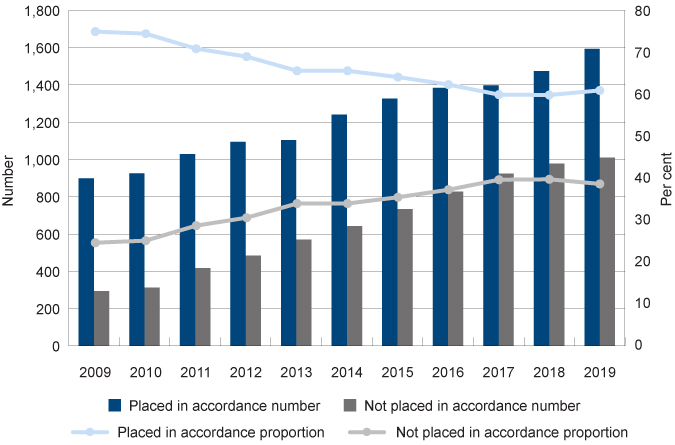

For more information on the placement of Aboriginal children in care refer to the next measure: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle.

Expenditure per child

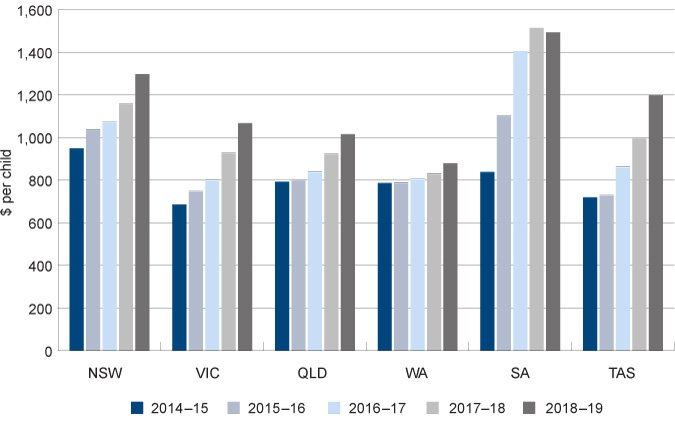

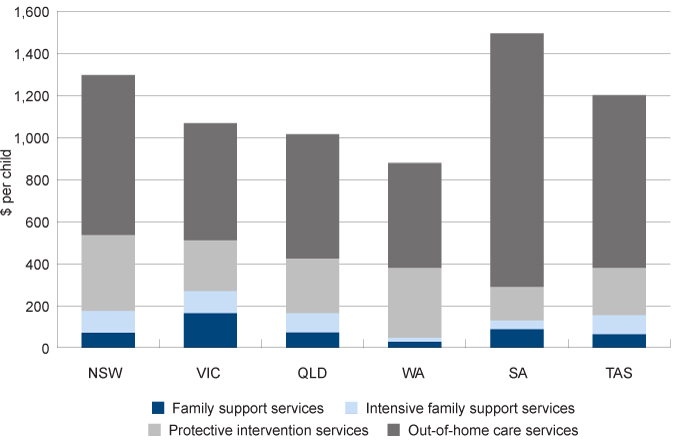

The 2020 Productivity Commission Report on Government Services shows that in 2018–19 compared to other Australian jurisdictions, the WA Government spent the second lowest amount (per child in the population) on child protection, intensive family support services and family support services.47

There has also been minimal increase in WA spending across these services over the last four years, in contrast to most other Australian jurisdictions.

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

NSW |

965.5 |

1,057.7 |

1,106.7 |

1,184.9 |

1,296.8 |

|

VIC |

688.4 |

748.1 |

825.3 |

945.4 |

1,067.4 |

|

QLD |

811.4 |

822.3 |

864.2 |

940.8 |

1,015.8 |

|

WA |

816.0 |

820.2 |

828.7 |

846.6 |

878.1 |

|

SA |

850.9 |

1,116.7 |

1,442.0 |

1,496.8 |

1,493.4 |

|

TAS |

743.9 |

756.3 |

884.8 |

1,017.4 |

1,200.5 |

|

ACT |

629.5 |

671.2 |

725.6 |

712.8 |

734.5 |

|

NT |

3,015.4 |

3,087.7 |

3,351.1 |

3,457.4 |

3,386.1 |

|

Australia |

854.8 |

920.8 |

992.9 |

1,072.1 |

1,159.9 |

Source: Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services 2020 – Child protection services, Table 16.A7 State and Territory Government real recurrent expenditure on all child protection services (2018–19 dollars)

* Real expenditure includes Protective intervention services, out-of-home care, intensive family support services and family support services.

Notes:

- Expenditure per child relates to children aged 0 to 17 years in the population.

- Population data used to derive rates are from the 2016 Census preliminary estimates.

- Refer to the Productivity Commission Report on Government Services for more information on comparatives and inclusions for each state and territory.

Real expenditure per child by category and jurisdiction, dollars per child, Australia excluding ACT and NT, 2014–15 to 2018–19

Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services 2020 – Child protection services, Table 16.A7 State and Territory Government real recurrent expenditure on all child protection services (2018–19 dollars)

Further analysis shows that WA has the lowest expenditure per child in the population on general family support services and intensive family support services of all states and territories with only 27.5 and 19.4 dollars per child respectively in 2018–19.

|

Family support services |

Intensive family support services |

Protective intervention services |

Out-of-home care services |

|

|

NSW |

70.6 |

103.7 |

360.8 |

761.8 |

|

VIC |

163.9 |

105.1 |

241.8 |

556.5 |

|

QLD |

72.0 |

91.2 |

260.1 |

592.4 |

|

WA |

27.5 |

19.4 |

332.4 |

498.7 |

|

SA |

87.1 |

42.3 |

159.7 |

1,204.4 |

|

TAS |

63.3 |

90.7 |

225.7 |

820.8 |

|

ACT |

32.9 |

55.4 |

159.9 |

486.3 |

|

NT |

751.8 |

87.9 |

396.1 |

2,150.3 |

|

Australia |

97.7 |

87.1 |

287.7 |

687.3 |

Source: Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services 2020 – Child protection services, Table 16.A7 State and Territory Government real recurrent expenditure on all child protection services (2018–19 dollars)

Note: Family support services are general services to families in need including general support, diversionary services and counselling. Intensive family support services are specialist services that aim to prevent the imminent separation of children from their primary caregivers as a result of child protection concerns and to reunify families where separation has already occurred. Protective intervention services functions of government that receive and assess allegations of child abuse, neglect and/harm to children and young people.

Real expenditure per child by category and jurisdiction, dollars per child, Australia excluding ACT and NT, 2018–19

Source: Productivity Commission 2020, Report on Government Services 2020 – Child protection services, Table 16.A7 State and Territory Government real recurrent expenditure on all child protection services (2018–19 dollars)

At the same time, in 2018–19 WA had the third highest expenditure per child in the population on protective intervention services (332.4 dollars per child).

Variations across jurisdictions can be due to different definitions and methodologies for calculating the total expenditure in each category. However, the results still highlight that WA is spending a disproportionate amount on tertiary services in the child protection system with significantly less being spent on primary and secondary services (family support services and intensive family support services).

International and Australian research has shown that while tertiary services are critical, investing in services for disadvantaged children and young people (and communities) which are focused on early intervention and prevention result in better outcomes than spending on tertiary services (e.g. child protection or youth justice).48

Early intervention is essential to improve the lives of children and young people and to strengthen families and communities. Recent analysis has highlighted the significant cost to Australia due to late intervention. This analysis estimated that the total cost to government for children and young people experiencing serious issues is $15.2 billion every year. These costs include the costs of child protection, youth justice, mental health issues, youth unemployment and youth homelessness.49

Endnotes

- Mullan K and Higgins D 2014, A safe and supportive family environment for children: key components and links to child outcomes – Occasional Paper No 52, Department of Social Services, p. 1.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Child Protection Overview, AIHW [website].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019, Child protection Australia: 2017–18, Child welfare series No 70, Cat no CWS 65, AIHW, p. 24.

- WA Department for Child Protection and Family Support (now Communities) 2014, Emotional abuse – Family and domestic violence policy, WA Government.

- Hunter C 2014, Effects of child abuse and neglect for children and adolescents, National child Protection Clearinghouse Resource Sheet, Australian Institute of Family Studies.