Participation in formal and informal child care

From birth, children require secure, stimulating and responsive care to ensure healthy early childhood development. Child care, that is care provided to a child by someone other than their parent(s) or legal guardian(s), can be provided formally, through child care providers or informally, through grandparents and other relatives, friends, neighbours or nannies.

Children’s participation in formal child care, as well as early childhood education programs (such as Kindergarten), are encompassed by the term early childhood education and care (ECEC). In this indicator, we will only be reporting on data relating to the child care component of ECEC.

Limited data is available on whether all WA children aged 0 to 5 years are provided with quality informal learning opportunities.

Overview

Research shows that participation in high quality ECEC is related to better cognitive and social development outcomes for children, particularly for children experiencing disadvantage.1, 2

The quality of care provided to children from birth to three years however is a key factor with poor quality care environments having been shown to have a detrimental effect on development.3 Formal child care services in Australia are regulated against National Quality Standards.

While one-half of all WA children under two are solely cared for by their parents or guardians (55%), a growing number of families use child care arrangements that involve formal or informal care or a combination of both.

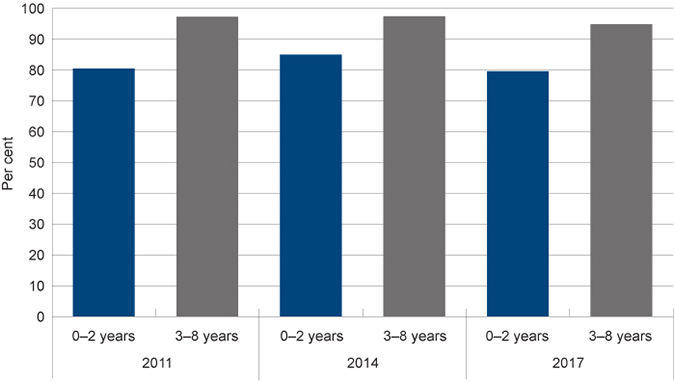

Type of care usually attended by children aged 0 to 5 years, by age group and type of care arrangement, per cent, WA, 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care, Australia, June 2017, cat no. 4402.0

Almost one in four (22.6%) WA children aged less than two years, and nearly one-half (44.9%) of two to three year-olds attend formal child care services.

Areas of concern

While increasing proportions of WA children aged 0 to two years are attending formal child care settings, children experiencing disadvantage are less likely to attend.

One-third of centre-based child care services are not meeting, but are working toward, National Quality Standards.

Endnotes

- Elliott A 2006, Early Childhood Education: Pathways to quality and equity for all children, Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Moore T 2006, Early childhood and long term development: The Importance of the Early Years, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, Literature review of the impact of early childhood education and care on learning and development: working paper. Cat. No. CWS 53, AIHW.

Last updated November 2018

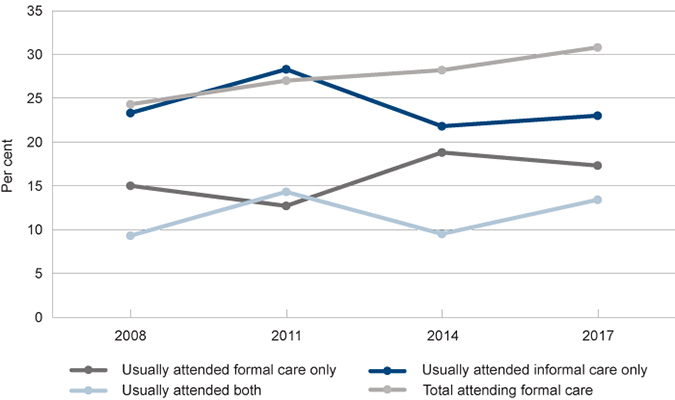

While many WA children are solely cared for by their parents, a growing number of families use child care arrangements that involve formal or informal care or a combination of both.

Children usually attending care aged 0 to 5 years, per cent, WA, 2008, 2011, 2014 and 2017

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4402.0 Childhood Education and Care Data Collection, 2008, 2011, 2014, 2017. The 2011 data was sourced from the Additional Datacubes, June 2011.

The data collection 4402.0 Childhood Education and Care by the Australian Bureau of Statistics presents data on the care arrangements used by WA families.1

|

Under 2 |

2 to 3 years |

4 to 5 years |

||||

|

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Long day care |

13,900 |

21.1 |

31,200 |

42.3 |

8,900 |

13.0 |

|

Before / after school care |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

7,900* |

11.5* |

|

Other formal care |

1,000 |

1.5 |

1,900 |

2.6 |

~ |

~ |

|

Total formal care |

14,900 |

22.6 |

33,100 |

44.9 |

15,800 |

23.1 |

|

Grandparent |

14,500 |

22.0 |

22,100 |

30.0 |

18,700 |

27.3 |

|

Other informal care |

5,800 |

8.9 |

5,300 |

7.2 |

7,600 |

11.1 |

|

Total informal care |

20,300 |

30.9 |

27,400 |

37.2 |

26,300 |

38.4 |

|

Did not usually attend care |

36,200 |

55.0 |

24,300 |

33.0 |

34,300 |

50.1 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4402.0 Childhood Education and Care Data Collection, June 2017

Note: Totals may not add as cells have been randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data and children could use more than one type of care.

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25 per cent to 50 per cent and should be used with caution.

Formal care is predominantly delivered in long day care settings but also includes family day care and out-of-school hours care.

In 2017, 22.6 per cent of WA children under the age of two and 44.9 per cent of two to three year-olds attended formal care, with the large majority of them receiving care in a long day care setting. As children transition to Kindergarten and Pre-primary from the age of four, a much lower proportion attends long day care (13.0%) but 23.1 per cent still receive formal care, mostly in outside school hours care.2

Overall, three in four WA families with children aged 0 to twelve years who are using formal care, do so for work-related reasons.3

Informal care occurs when families rely on grandparents, other relatives, friends, neighbours or nannies to care for their children. Thirty-one per cent of children under the age of two received informal care in 2017, as did 37.2 per cent of two to three year-olds and 38.4 per cent of four to five year-olds.

In terms of informal care arrangements, grandparents are the most common informal care providers for their grandchildren. Furthermore, a higher proportion of WA children aged 0 to two years are cared for by their grandparents than in a long day care environment. Strong relationships are important to children’s positive learning and life outcomes and informal care arrangements with trusted family members and local community help provide a supportive environment for the family.

The main reason families use informal care for their children from birth to 12 years is to enable parents to work (60.5%) and for personal reasons (27.0%).4

Around one in two WA children under the age of two years (55.0%) and one in three children aged three to four years (33.0%) are not participating in any regular non-parental care arrangement.

Parents who use more than ten hours of care a week for their 0 to two year-old are very likely to choose formal care. If they require less than ten hours of care a week, they are more likely to choose informal care arrangements. This trend is the same but less pronounced for three to five year-olds.5

The participation of Australia’s 0 to two year-olds in formal care is similar to the OECD average. As is the participation of three to four year-olds in Pre-school education (69% for Australia compared to 71% across the OECD). Australia’s participation rates at age four (Kindergarten in WA) have increased significantly since 2005 (from 53% in 2005 to 85% in 2014).6

While children from disadvantaged backgrounds stand to benefit the most from quality ECEC, they are least likely to attend.7 Barriers to participation for these children include cost, transport, lack of interest in and knowledge of the benefits of ECEC.8 Research into Aboriginal families across Australia also found that a distrust of institutions and concerns about being judged were significant barriers.9

The ABS data is not disaggregated by Aboriginal status.

The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC) collects data on two groups of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children those aged six to 18 months (B cohort) and three and-a-half to five years (K cohort) when the study began in 2008.10 The Wave 3 report published in 2012 reported on the children’s participation in child care and play groups.

This study found that around 27 per cent of the participating children attended a play group or other baby group. The main reasons cited by parents for their children not attending a play group or equivalent was the ‘child not needing it’ (32.0%) and the child is currently attending day care, Kindergarten or Pre-school (18.0%).11

About 33 per cent of children in the B cohort attended some form of child care, day care or family care. Children attended child care mostly because of the primary carers’ work commitments (47.7%) or because the primary carer thought it would be good for the child’s social development (34.6%).12

Similar to the broader population grandmothers were the most common informal carer (44.6%). In contrast to the broader population, in less than three per cent of cases only the primary carer looked after the child.13

No data is available on the participation of WA Aboriginal children in formal and informal child care.

A new quality standard in ECEC services was developed in 2012, in which all Australian governments agreed to work together to provide better educational and developmental outcomes for children.14 The National Quality Framework (NQF) is a national approach to regulation, assessment and quality improvement for ECEC and outside school hours care services across Australia.15

ECEC services are assessed against the National Quality Standard (NQS) by the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA).16

In WA, ECEC programs delivered in a school setting (that is Kindergartens) are administered by the Department of Education (not ACECQA) and quality data is not published. The following data from ACECQA is therefore principally reporting on services delivered in child care settings and provides a good indication of how the formal child care sector is performing.

|

Number |

Per cent |

|

|

Long day care |

654 |

55.4 |

|

Preschool/Kindergarten |

26 |

2.2 |

|

Outside school hours care |

460 |

39.0 |

|

Family day care |

39 |

3.3 |

|

Other |

2 |

0.2 |

|

Total |

1,181 |

100.0 |

Source: ACECQA 2018, NQF Snapshot Q1 2018, A quarterly report from the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, May 2018.

|

WA |

Australia |

|||

|

Q1 2016 |

Q1 2017 |

Q1 2018 |

Q1 |

|

|

Number of services |

1,145 |

1,177 |

1,181 |

15,766 |

|

Number of services with quality rating |

610 |

942 |

1,070 |

14,691 |

|

Proportion of services with a quality rating |

53.3% |

80.0% |

90.6% |

93.2% |

|

Overall quality rating results |

||||

|

Percentage Excellent |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Percentage Exceeding |

24.0% |

24.0% |

28.0% |

33.0% |

|

Percentage Meeting |

38.0% |

38.0% |

38.0% |

44.0% |

|

Percentage Working Towards* |

38.0% |

37.0% |

33.0% |

23.0% |

Source: ACECQA NQF Snapshots Q1 2016, 2017, 2018, Quarterly reports

* Working Towards the National Quality Standards means the service provides a safe education and care program but there are one or more areas identified for improvement.17

The number of WA services with a quality rating has increased significantly over the last three years from 53.3 per cent to 90.6 per cent. In spite of falling short of the national average of 93.2 per cent, this is a positive development.

In the first quarter of 2018, 66 per cent of assessed WA services met or exceeded the NQS and as such WA is behind the national average (77.0% of services met or exceeded the NQS). A significant proportion of WA services with quality rating are in the category ‘Working Towards’. There are no services in WA rated with ‘Significant Improvement Required’.18

While data is not available for WA, services across Australia that are rated overall as ‘Working Towards’ the NQS or Significant Improvement Required are disproportionately located in areas of socio-economic disadvantage.19

For further information on the WA results, refer to the latest NQF Snapshot.

Endnotes

- Formal care includes long day care and family day care and informal care includes care provided by a non-resident parent, a nanny, brother or sister or other relative. The survey was conducted in urban and rural areas and excluded people living in Indigenous communities.

- Baxter JA 2015, Child care and early childhood education in Australia, Facts Sheet 2015, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Childhood Education and Care 2017, Cat No 4402.0, Table 7: Children aged 0-12 years who usually attended care: Reasons attended care—Western Australia.

- Ibid.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Custom report - Children aged 0-5 years who usually attended care: Type of care usually attended by usual weekly hours of care—Western Australia [unpublished].

- OECD 2016, Starting Strong IV: Early Childhood Education and Care: Data Country Note – Australia, OECD.

- Cloney D et al 2016, The selection of ECEC programs by Australian families: Quality, availability, usage and family demographics, Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, Vol 41, No 4.

- Productivity Commission 2014, Childcare and Early Childhood Learning: Overview and Recommendations, Inquiry Report No. 73, Commonwealth of Australia, p. 9.

- Kellard K and Patton H 2016, Indigenous participation in Early Childhood Education and Care – Qualitative Case Studies, The Social Research Centre, p. 23 & 40.

- Department of Social Services, Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children [website].

- Department of Social Services 2012, Footprints in Time: The Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children: Key summary report from Wave 3, Australian Government, p. 10.

- Ibid, p. 11.

- Ibid, p. 12. – Note: This statistic includes the ‘other parent’ as a non-primary carer.

- The National Quality Framework introduced a new quality standard to improve education and care across long day care, family day care, preschool/Kindergarten, and outside school hours care services. The National Quality Framework took effect on 1 January 2012 with key requirements being phased in over time. Requirements such as qualification, educator-to-child ratios and other key staffing arrangements will be phased in between 2012 and 2020.

- This approach includes improving educator and child ratios, increasing the skills and qualifications of carers and better supporting the developmental needs, interests and experiences of each child. For further information refer to the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority website.

- The NQS includes seven quality areas that are important outcomes for children. Services are assessed and rated by their regulatory authority against the NQS, and given a rating for each of the seven quality areas and an overall rating based on these results. The Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) regulates and publishes the ratings of the various services. Refer ACECQA NQF Snapshot, Q2, 2018.

- ACECQA 2018, Guide to the National Quality Standard Assessment and ratings process: 3. National Quality Standard Assessment and Rating, ACECQA, p. 320.

- ACECQA 2018, NQF Snapshot Q1 2018, A quarterly report from the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, May 2018, Table 6: Overall quality ratings by jurisdiction.

- Torii K et al 2017, Quality is key in Early Childhood Education in Australia, Mitchell Institute Policy Paper No 01/2017, Mitchell Institute, p. 2.

Children in out-of-home care can benefit from high quality formal child care that exposes them to a nurturing and responsive learning environment while also providing respite for the child’s carer(s). Early childhood education and care has a beneficial impact on a child’s cognitive, emotional and social development as well as improving later school and life outcomes.1 Children in out-of-home care should have equal access to these services.

At 30 June 2019, there were 1,341 WA children in care aged between 0 and four years, more than one-half of whom (56.8%) were Aboriginal.2

No data exists on the participation in formal or informal child care of 0 to three year-old WA children in care.

The Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study (POCLS) is a longitudinal study on out-of-home care (OOHC) in NSW which examines the developmental wellbeing of children and young people in care aged 0 to 17 years.3 The study collects data regarding the type, and number of hours, of child care attended by children in care but does not assess the quality of child care attended.

Preliminary findings in this study show that 52 per cent of nine to 35 month-old children, 90 per cent of three year-olds and 96 per cent of four to five year-olds attend some form of child care or early childhood education. It was noted that it was not possible to determine the proportion of children receiving an early childhood education program from this data.4 As low quality care can have a negative impact on a child’s social-emotional difficulties, a recommendation from the study is that case workers assist carers to identify high quality child care providers.5

Endnotes

- Vandenbroeck M et al 2018, Benefits of Early Childhood Education and Care and the conditions for obtaining them, European Expert Network on Economics of Education Analytical Report No. 32, European Commission.

- Department of Communities 2019, Annual Report: 2018-19, WA Government p. 26.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies et al 2015, Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study: Outcomes of children and young people in Out-of-Home care in NSW. Wave 1 baseline statistical report, NSW Department of Family and Community Services.

- Ibid, p. 126.

- NSW Department of Family and Community Services 2016, The early learning and child care experiences of children in out-of-home care, FACSAR Evidence to Action Note, December 2016, NSW Department of Family and Community Services.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Disability, Ageing and Carers data collection reports that approximately 5,200 WA children and young people (3.1%) aged 0 to four years have a reported disability.1

High quality early childhood education and care is informed by child-centred educational programs and practices and allows for individualised support that will address the diverse learning needs and abilities of all children.2

In the case of disability, high quality formal child care can enable early assessment and intervention. It can also assist families to find the appropriate support and services that can help their child develop and learn to their full potential. Further, formal and informal care arrangements can also provide regular respite to parents and carers of children with disability.

In Australia, all early childhood service providers have a legislative obligation to make reasonable adjustments for children with disability under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992.

No data exists on the formal and informal care arrangements of children with a disability.

Endnotes

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, Disability, Ageing and Carers: 2018, Western Australia, Table 1.1 and 1.3.

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation 2009, Inclusion of Children with Disabilities: The Early Childhood Imperative, UNESCO Policy Brief on Early Childhood, No 46, April-June.

Research shows that high quality early childhood education and care (ECEC) can provide the foundations for future learning, enhanced intellectual development, sociability and concentration, language and cognitive development and school readiness.1,2

Quality care and education can occur in a formal and informal context. Young children are learning constantly and the quality and reliability of a young child’s relationships are essential to healthy development. Having nurturing and attentive carers is a key measure of quality in any child care setting.3,4

Quality is important; research has found that poor quality child care can have a detrimental effect on a child’s language, cognitive development and social behaviour.5 For very young children (0 to two year-olds) who are not disadvantaged at home, the benefits of attending child care are contested.6

The quantity of care also plays a role in shaping child development. There is some evidence that longer attendance at day care for very young children may be associated with poorer developmental outcomes.7,8

More than one-half of WA children under the age of two are looked after solely by a parent and it is therefore important to support parents in providing a nurturing and stimulating home learning environment. For more information, see the Informal learning opportunities. indicator.

High quality child care can be effective in supporting parents in their parenting role and helping families form social networks.9 Furthermore, participation in early learning and care helps lay the foundations for a positive working relationship between parents and educators that will be required to ensure a child’s successful transition to, and positive engagement with, school.10

There is evidence that children from disadvantaged backgrounds gain particularly strong benefits from attending high quality child care as it provides them with a supportive environment for cognitive and socio-emotional stimulation and learning.11,12

The particular benefits of quality ECEC for children experiencing disadvantage or with special needs include early identification of any learning or developmental difficulties.13 Early intervention is most effective when it addresses both children’s and their families’ needs, taking into account the context in which they live.14

However, lack of availability of quality ECEC in low socioeconomic areas is a barrier to participation for children experiencing disadvantage. Achieving equitable outcomes for all WA children involves ensuring access to high quality affordable early learning programs in areas close to where they live. Increasing the supply and quality of ECEC in low socioeconomic areas requires specific and targeted policy intervention.15

For Aboriginal children, attendance at early childhood services cannot be separated from child, family and community health and wellbeing.16 Early childhood education and care in the Aboriginal context, is more effective when programs are culturally sensitive and actively involve the community in planning, development and implementation.17

Data gaps

Data about the quality of informal care that children receive is limited. Longitudinal data on children solely receiving informal care would be beneficial to provide a better understanding of the scope and quality of care provided to children and what supports are needed to assist carers.

Data on the early learning experiences of children in care is critical; without this it is difficult to assess whether children in care are being provided with consistent and equitable access to early learning opportunities.

Endnotes

- Gorey KM 2001, A meta-analytic affirmation of the short-and-long-term benefits of educational opportunity, School Psychology Quarterly, Vol 16 No 1.

- OECD 2017, Starting Strong 2017, Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing.

- Centre for Community Child Health 2007, Early years care and education, Policy Brief No 8, The Royal Children’s Hospital.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2004, Young children develop in an environment of relationships: Working Paper No 1, Harvard University.

- Productivity Commission 2014, Childcare and Early Childhood Learning: Overview, Inquiry Report No. 73, Productivity Commission.

- For a discussion of the literature, refer to: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, Literature review of the impact of early childhood education and care on learning and development: working paper, Cat No CWS 53, AIHW.

- Bowes J et al 2009, From Child Care to School: Influences on Children’s Adjustment and Achievement in the Year before School and the First Year of School, Findings from the Child Care Choices Longitudinal Extension Study, NSW Department of Community Services.

- Holzinger LA and Biddle N 2017, The relationship between early childhood education and care (ECEC) and the outcomes for Indigenous children: evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), Working Paper No 103/2015, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University.

- Harrison LJ et al 2012, Child care and early education in Australia, Social Policy Research Paper 40, The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Department of Social Services, p. 161.

- Ibid.

- Elliott A 2006, Early Childhood Education: Pathways to quality and equity for all children, Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Moore T 2006, Early childhood and long term development: The Importance of the Early Years Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth.

- Productivity Commission 2014, Childcare and Early Childhood Learning: Overview, Inquiry Report No 73, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Sims M 2011, Early childhood and education services for Indigenous children prior to starting school, Resource Sheet No 7, Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Cloney D et al 2016, Variations in the Availability and Quality of Early Childhood Education and Care by Socioeconomic Status of Neighborhoods, Early Education and Development, Vol 27 No 3, p. 396-397.

- Sims M 2011, Early childhood and education services for Indigenous children prior to starting school, Resource Sheet No 7, Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2013, What works to overcome Indigenous disadvantage: key learnings and gaps in the evidence 2011-12, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Institute of Family Studies.

For more information on early childhood education and care refer to the following resources:

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015, Literature review of the impact of early childhood education and care on learning and development: working paper, Cat No CWS 53, AIHW.

- Holzinger LA and Biddle N 2017, The relationship between early childhood education and care (ECEC) and the outcomes for Indigenous children: evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children (LSIC), Working Paper No 103/2015, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University.

- O’Connell M et al 2016, Quality Early Education for All: Fostering creative, entrepreneurial, resilient and capable learners, Mitchell Institute policy paper No 01/2016, Mitchell Institute.