Developmental screening

Early childhood development sets the trajectory for physical health and cognitive, emotional and behavioural wellbeing through childhood, adolescence and into adulthood.

Developmental health screening is an important mechanism to identify and manage any issues early to ensure children have the best possible chance for positive life outcomes.

Last updated February 2022

Data is available on whether WA children are being screened for health and developmental issues.

Overview

Children in WA can access five child health checks between birth and two years, plus the School Entry Health Assessment in the first year of school attendance.

Screening programs of this nature generally have three key goals: early detection of developmental and health problems and if necessary connection with services for further assessment or intervention; health promotion to families; and identification of children who may need more support.1

For information on the School Entry Health Assessment refer to the Developmental screening indicator in the 6 to 11 age group.

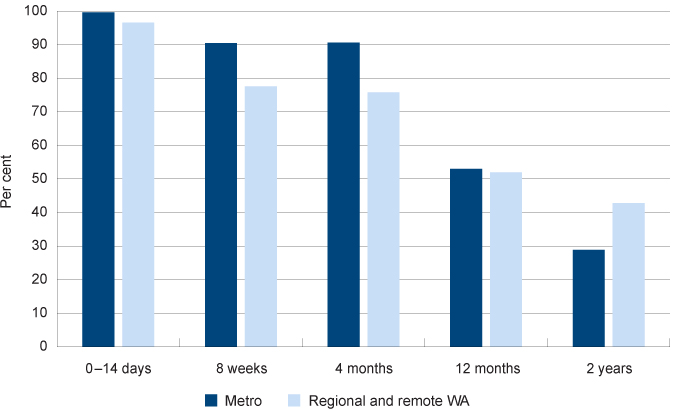

Almost all eligible WA children in the Perth metropolitan area (98.0%) and regional and remote WA (96.6%) received the 0 to 14-day child health check in 2019–20.

In 2019–20, between 81.5 per cent and 92.1 per cent of Perth metropolitan children with a completed Ages and Stages Questionnaires® (ASQ) were developmentally on track in all ASQ domains at four months of age. A high proportion (88.6%) of Perth metropolitan children with a completed ASQ were on track in the social emotional domain at age two years.

Areas of concern

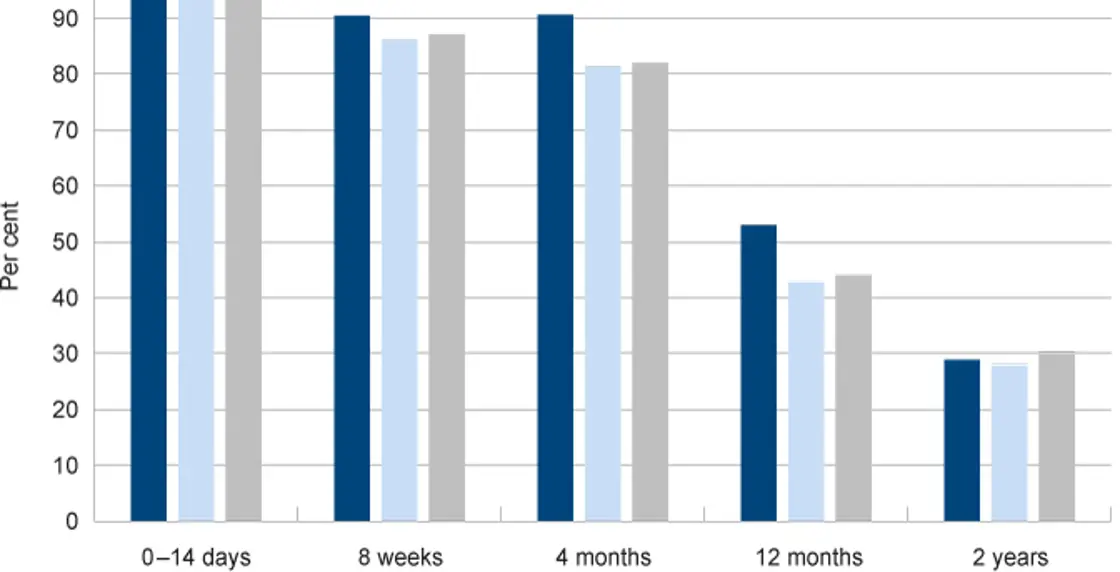

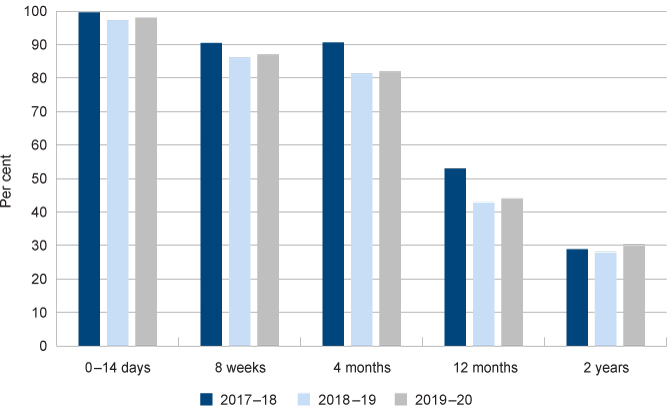

While attendance at early child health checks is generally high, a low proportion of eligible children in the Perth metropolitan area received the 12-month child health check (44.1%) and the two-year child health check (30.2%) in 2019–20.

The proportion of children in the metropolitan area attending each child health check, except for the two years’ check, decreased from 2017–18 to 2019–20. The 2019–20 attendance was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic response.

Proportion of children receiving child health checks in metropolitan Perth by age, per cent, WA, 2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20

The parents and carers of Aboriginal children are less likely to complete the ASQ questionnaires than parents/carers of non-Aboriginal children. This is likely due to language barriers and the cultural appropriateness of the services and the ASQ questionnaires.

There is no publicly available data on whether the 1,536 children in care in WA under six years of age (at 30 June 2021)2 received health and developmental checks or have been assessed for developmental issues.

Other measures

Immunisation is often considered a key measure of child wellbeing. Immunisation has not been selected as a measure in the Indicators of wellbeing. This is not because immunisation is not important – it is critical for children’s wellbeing – however, immunisation rates for WA’s children and young people are adequately monitored through various data sites, and policy settings are firm.

For information on immunisation rates in WA refer to the AIHW Healthy Community Indicators website which reports interactively on immunisation rates for regions across Australia.

Ear and hearing health is also an important measure of child wellbeing, as hearing loss can affect the development of speech, language and learning. Ear disease and associated hearing loss are particularly prevalent among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.3 The reasons for this are complex and include experiences of poverty and environmental factors such as lack of community infrastructure, access to clean drinking water and access to appropriate and quality services.4 Hearing loss, particularly undiagnosed hearing loss, can have long lasting impacts on children’s wellbeing including school truancy, behavioural issues and social isolation.5,6

Ear health is not specifically included as one of the measures within the Indicators of wellbeing. The child health and development checks are the primary mechanism for identifying issues with ear and hearing health, therefore, if children are attending the full complement of health checks, issues with their hearing should be identified.

Children will have the best chance to have healthy hearing when any issues are identified early and follow-up services are provided to support their families to ensure optimal ear health. It is also important that underlying environmental issues that impact on ear and hearing health for children are addressed at the community level.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) publishes data on ear health as part of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework.

For further information on ear health, refer to the WA Child Ear Health Strategy 2017–2021, the WA Auditor General’s 2019 report on Improving Aboriginal Children’s Ear Health and the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet Ear Health.

Endnotes

- McLean K et al 2014, Screening and surveillance in early childhood health: Rapid review of evidence for effectiveness and efficiency of models; Murdoch Children Research Institute.

- Department of Communities 2019, Child Protection Activity Performance Report 2017–18, WA Government p. 17.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018, Australia’s Health 2018 - 6.4 Ear health and hearing loss among Indigenous children, AIHW.

- WA Department of Health and Department of Aboriginal Affairs, WA Child Ear Health Strategy 2017–2021, WA Government.

- Burns J and Thomson N 2013, Review of ear health and hearing among Indigenous Australians, Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, Vol 13 No 4.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018, Australia’s Health 2018 - 6.4 Ear health and hearing loss among Indigenous children, AIHW.

Last updated February 2022

Optimising a child’s chance to have a healthy and productive life requires a holistic approach which includes a safe and nurturing home and community environment, access to appropriate health and family services and early identification of risk factors and developmental issues.1,2 Health and development screening is a key component used within Australia to assist in early identification of health and developmental issues.

This measure uses data from the WA Department of Health to report on the proportion of children receiving age-appropriate child health and development checks.

Child health and development checks are a critical service that provide an entry point to other child health services; when they are not performed developmental and health problems may not be detected, and intervention may be delayed. As children get older the developmental pathways initiated in early childhood become more difficult to change.3 Therefore, intervention when children are young is the most effective time to make a difference.

WA Health offers regular free health and development checks to children between birth and school entry under a universal schedule. For data on school entry health screenings refer to the Developmental screening indicator for children aged 6 to 11 years.

Health services for children and young people in the Perth metropolitan area4 are delivered by the Child and Adolescent Health Service, while health services in regional and remote WA are delivered by the WA Country Health Service.

In 2010, the WA Auditor General reviewed the WA Department of Health’s universal child health check system and found that many children were missing out on checks.5 In 2014, the Auditor General performed a follow-up review and found that while the Department had increased the number of health checks being performed, they were still not keeping up with the growth in demand.

During 2017–18 a revised service model for child health checks was implemented across the state.6 Some of the key changes were:

- An updated universal child health check schedule (0–14 days, eight weeks, four months, 12 months, two years and school entry).

- Adopting a more flexible service delivery approach through drop-in sessions or Universal Plus contacts offered to families where additional support is required.

Drop-in sessions are offered at child health centres and other community locations, providing parents and carers with an opportunity for a brief clinical discussion with their child health nurse without the need for an appointment.

Universal Plus contacts are generally provided to families who require additional support and may be provided face-to-face or by telephone.

|

Contact type |

Eligible children |

Children completing check |

Percentage of eligible |

|

0–14 days |

25,954 |

25,435 |

98.0 |

|

8 weeks |

26,245 |

22,822 |

87.0 |

|

4 months |

26,387 |

21,622 |

81.9 |

|

12 months |

26,351 |

11,629 |

44.1 |

|

2 years |

25,343 |

7,649 |

30.2 |

|

Universal Plus |

35,368 |

||

|

Drop-in |

30,981 |

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service from Child Development Information System and contracted service database to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

* Data includes only those child health checks of mothers with a residential address in the Perth metropolitan area. Mothers from regional or remote WA who attend child health checks in Perth are not included in this data – where possible they are recorded against regional/remote child health checks.

There is a significant reduction in the number of eligible children attending child health checks as they age. This is of concern as some developmental issues are only able to be identified at the 12-month and two-year checks.

Many families attend drop-in sessions or Universal Plus checks which do not coincide with the universal contacts timeframe, these contacts accounted for 42 per cent of all contacts with child health nurses during 2019–20.7 This is a similar proportion to 2017–18.

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the delivery of child health services. In particular, drop-in services were not available from March to December 2020. Further, face-to-face contact was reduced and parents/carers were encouraged to attend telephone/telehealth appointments. These telephone/telehealth appointments were recorded as ‘Universal Plus’ contacts.

Overall, attendance at child health checks in the Perth metropolitan area decreased since 2017–18. In particular, attendance at the 12-month child health check has decreased from 53 per cent in 2017–18 to only 44.1 per cent of eligible children attending an appointment in 2019–20. This will in part be due to the COVID-19 service changes for just over three months of the year, although this level of decrease is not evident in the other child health checks.

|

Contact type |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|

0–14 days |

99.6 |

97.3 |

98.0 |

|

8 weeks |

90.5 |

86.1 |

87.0 |

|

4 months |

90.6 |

81.3 |

81.9 |

|

12 months |

53.0 |

42.9 |

44.1 |

|

2 years |

28.9 |

28.0 |

30.2 |

Source: Custom reports provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of children seen at universal contact points, metropolitan Perth, per cent, 2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20

Source: Custom reports provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Child health checks in regional and remote WA are managed by the WA Country Health Service (WACHS).

Almost all mothers and babies (96.6%) in regional and remote WA attend the 0-to-14-day check. However, only three-quarters (77.6% and 75.8% respectively) of mothers and babies attend the eight-week and four-month check.

|

Eligible children |

Children completing |

Percentage of eligible |

|

|

0–14 days |

6,153 |

5,942 |

96.6 |

|

8 weeks |

6,226 |

4,831 |

77.6 |

|

4 months |

6,310 |

4,783 |

75.8 |

|

12 months |

7,638 |

3,970 |

52.0 |

|

2 years |

6,636 |

2,840 |

42.8 |

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

A greater proportion of mothers and children in regional and remote areas attend the 12-month and two-year child health checks than in the metropolitan area – although still only one-half (52.0%) or less than one-half (42.8%) respectively.

|

Perth |

Regional and |

|

|

0–14 days |

98.0 |

96.6 |

|

8 weeks |

87.0 |

77.6 |

|

4 months |

81.9 |

75.8 |

|

12 months |

44.1 |

52.0 |

|

2 years |

30.2 |

42.8 |

Source: Custom reports provided by the Child and Adolescent Health Service and WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of eligible children attending child health checks by metropolitan and regional and remote WA, per cent, WA, July 2019 to June 2020

Source: Custom reports provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service and WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

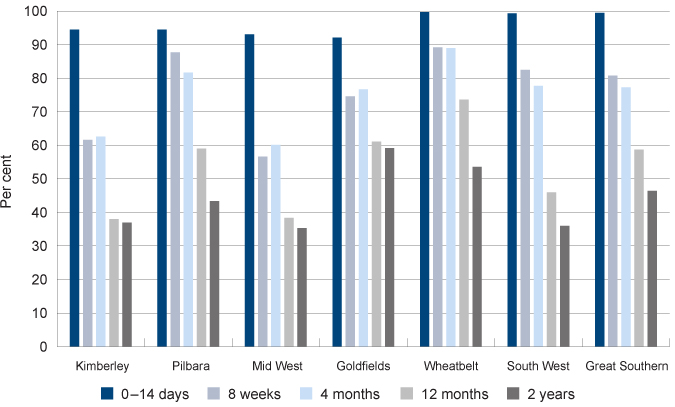

There is also significant variation in attendance across WA regions.

|

Kimberley |

Pilbara |

Mid West |

Goldfields |

Wheatbelt |

South West |

Great Southern |

Total |

|

|

0–14 days |

94.5 |

94.5 |

93.1 |

92.1 |

99.7 |

99.3 |

99.5 |

96.6 |

|

8 weeks |

61.6 |

87.7 |

56.6 |

74.6 |

89.2 |

82.5 |

80.8 |

77.6 |

|

4 months |

62.6 |

81.7 |

60.1 |

76.7 |

89.0 |

77.7 |

77.3 |

75.8 |

|

12 months |

38.0 |

59.0 |

38.4 |

61.1 |

73.6 |

46.0 |

58.7 |

52.0 |

|

2 years |

37.0 |

43.4 |

35.3 |

59.2 |

53.6 |

36.0 |

46.4 |

42.8 |

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of eligible children attending child health checks delivered in regional and remote WA by region, per cent, WA, July 2019 to June 2020

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

During 2019–20, the WACHS implemented a single clinical information system across its network which has improved data completeness and accuracy. This also enables additional reporting of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children attending child health checks highlighting some significant differences across geographical regions in WA.

In the Pilbara, Wheatbelt and the Great Southern, the proportion of Aboriginal children attending child health checks is greater than non-Aboriginal children. In the Mid West, Goldfields and the South West the proportion attending is substantially lower.

|

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|||

|

Number eligible |

Per cent attended |

Number eligible |

Per cent attended |

|

|

Kimberley |

358 |

86.6 |

246 |

89.4 |

|

Pilbara |

199 |

87.9 |

644 |

83.9 |

|

Mid West |

191 |

80.1 |

604 |

92.2 |

|

Wheatbelt |

76 |

100.0 |

647 |

95.8 |

|

Goldfields |

109 |

82.6 |

637 |

92.0 |

|

Great Southern |

22 |

100.0 |

611 |

97.1 |

|

South West |

95 |

62.1 |

1,714 |

99.2 |

|

Total |

1,050 |

84.3 |

5,103 |

94.4 |

Source: Custom reports provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Note: This table does not include a small number of children with no specified ethnicity in each region.

There is limited information available on whether children recommended for referral as a result of a child health check have received appropriate services for any issues identified.

In the 2018 calendar year, 14 per cent of children in the Perth metropolitan area receiving a child health check were referred to other services.8

Referrals in the Perth metropolitan area are tracked electronically within the Child Development Information System (CDIS). The CDIS also records if referrals are declined by the parent/carer, which provides the child health nurse with an opportunity to take further action, where appropriate.

The CDIS record enables the child health nurses to monitor individual outcomes following a referral to Child Development Services (CDS). These can be centrally reported and monitored. Where children are referred to external health care providers (including GPs and medical specialists) outcomes data cannot be centrally monitored. In 2018, 16 per cent of referrals from metropolitan child health services were to external providers.9

In 2010 the Auditor General noted that CDS has historically had significant waitlists for therapy and treatment of identified developmental delays.10

In 2020–21 the metropolitan CDS accepted 30,594 referrals which is an increase of 14 per cent from the previous year.11

The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents noted in their recently published report: Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change that with regard to mental health services:

“A consequence of demand growing faster than capacity is that every day clinicians are assessing referrals and prioritising access only to the most high-risk children, usually aged between 12-to-15. This has led to proportionally fewer infants and children under the age of 12 being able to access specialist mental health services than in the past, even if they are severely unwell.”

The Taskforce also found that less than one-in-five children (aged 0 to 17 years) who are referred to a service are accepted for treatment. They noted that some health professionals stated they have stopped referring to public mental health services.12

Wait times for other child development services can also be significant.

|

Speech pathology |

Occupational therapy |

Physiotherapy |

|

|

Perth* |

8.7 |

7.8 |

9.0 |

|

Kimberley |

1.9 |

7.5 |

1.4 |

|

Pilbara |

1.2 |

0.8 |

2.0 |

|

Mid West |

2.3 |

2.1 |

1.8 |

|

Goldfields |

2.4 |

4.1 |

0.9 |

|

Wheatbelt |

0.9 |

1.9 |

1.0 |

|

South West |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

|

Great Southern |

1.3 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

Source: Hansard, Legislative Council WA Parliament, 12 October 2021

* This represents the median wait time for the metropolitan Child Development Service.

Note: The regional wait times are for services provided by the WACHS and have been calculated from the number of days divided by 30 to provide an equivalent to the Perth data.

Endnotes

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council 2011, National Framework for Universal Child and Family Health Services, Australian Government.

- Moore TG et al 2017, The First 1000 Days: An Evidence Paper – Summary, Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Centre for Community Child Health 2018, Policy Brief: The First Thousand Days – Our Greatest Opportunity, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- A number of outer metropolitan area post codes classified as Inner Regional (ABS Remoteness Index) fall within the Child and Adolescent Health Service (CAHS) Community Health catchment. These include Bullsbrook, Childlow, Chittering, Gidgegannup, Jarrahdale, Two Rocks and Waroona. Services provided to children and families living in these areas are included in the above. All other metropolitan postal codes are classified as Major Cities.

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Report 11, November 2010.

- This redesign was in response to the WA Metropolitan Birth to School Entry Universal Health Service Delivery Model Review (the Review) completed by Professor Karen Edmond, Consultant Paediatrician and Public Health Physician.

- Information provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People by the Department of Health Child and Adolescent Health service [unpublished].

- Information provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People by the Department of Health Child and Adolescent Health service [unpublished].

- Information provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People by the Department of Health Child and Adolescent Health service [unpublished].

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Report 11, November 2010, p. 14–15.

- Child and Adolescent Health Service, Annual Report 2020-21, Department of Health.

- The Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents 2021, Emerging Directions: The Crucial Issues For Change: Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents aged 0–18 in Western Australia, Government of Western Australia.

Last updated February 2022

Screening for developmental issues in infants and young children is critical to detect and subsequently manage any identified issues. Research suggests that up to 15 per cent of children under the age of five years may have difficulties in more than one area of development.1

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires® (ASQ) is a developmental screening and monitoring system designed to identify infants and young children in need of further assessment. The ASQ provides developmental information in five key domains: communication, gross motor skills, fine motor skills, problem solving and personal/social skills.2 Social-emotional health is administered via the Ages and Stages Questionnaire®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE2).3

The ASQ has been validated against a number of standard measures and shown to be administratively simple and flexible, low-cost and suitable for diverse populations.4

In WA, the ASQ third edition (ASQ-3) is the primary child developmental screening tool used by community health nurses. Since July 2017, the ASQ-3 has been universally offered to parents/carers at the four-month, 12-month and two-year child health checks.5

Parents/carers complete the ASQ-3 relevant for their child’s age. The resulting score will categorise the child into ‘on track’, ‘requiring monitoring’ or ‘requiring referral or further assessment’ for each domain. Children suspected of having a developmental delay will then be referred to other services. It should be noted that the ASQ-3 does not provide a diagnosis, it is a tool for referral.

Data on the completion and results of the ASQ-3 at the population level is not publicly reported. The following data has been provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the WA Child and Adolescent Health service.

Completion of ASQ-3 and ASQ:SE2

As with the child health checks, not all eligible children are assessed through the ASQ-3 or ASQ:SE2. At the 4-months of age check, 60.5 per cent of children attending had a completed ASQ-3 and 52.9 per cent had a completed ASQ:SE2.

However, by 12-months, only 37 per cent of all eligible children in metropolitan Perth had a completed ASQ-3 and 35.5 per cent had a completed ASQ:SE2.

|

ASQ-3 (unique clients with |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients |

|

|

4 months |

60.5 |

52.9 |

|

12 months |

37.0 |

35.5 |

|

2 years |

26.6 |

19.5 |

Source: Custom report provided by WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Services (CAHS) to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Consistent with the child health checks, the proportion of eligible children in Perth with a completed ASQ-3/ASQ:SE2 decreases significantly with age.

Furthermore, not all children who attend child health checks have a completed ASQ-3/ASQ:SE2. For example, in 2019-20 only 73.8 per cent of children attending the 4-month child health check have a completed ASQ-3 and 64.6 per cent have a completed ASQ:SE2.

|

ASQ-3 (unique clients with |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients |

|

|

4 months |

73.8 |

64.6 |

|

12 months |

83.9 |

80.4 |

|

2 years |

88.0 |

64.5 |

Source: Custom report provided by WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Services (CAHS) to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

At each of these child health checks children are less likely to be assessed for social-emotional health through the ASQ-SE2. The ASQ:SE is a valid tool for preliminary screening for mental health issues6 which is increasingly recognised as a significant issue for children and young people. For more information refer to the Mental health measure.

The proportion of children in the metropolitan area who attended child health checks with a completed ASQ-3 and ASQ:SE2 increased since 2017–18 across most health checks.

|

ASQ-3 (unique clients with |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients with |

|||

|

2017–18 |

2019–20 |

2017–18 |

2019–20 |

|

|

4 months |

64.0 |

73.8 |

53.0 |

64.6 |

|

12 months |

67.0 |

83.9 |

63.0 |

80.4 |

|

2 years |

80.0 |

88.0 |

65.0 |

64.5 |

Source: Custom report provided by WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Services (CAHS) to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Evidence suggests that the standard ASQ questionnaires may not be linguistically or culturally appropriate for many Aboriginal families or for families from a culturally and linguistically diverse background.7,8,9

The Child and Adolescent Health service recommends ASQ-TRAK – a modified version of the ASQ-3 which has been adapted to be more culturally appropriate for Aboriginal children10 – for metropolitan Aboriginal families, where appropriate.11

In the metropolitan area, the proportion of Aboriginal children with a completed ASQ (3 or TRAK)/ASQ:SE2 while attending a child health check was consistently lower than for non-Aboriginal children.

|

ASQ-3/TRAK (unique clients |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients |

|||||

|

All |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

All |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

4 months |

73.8 |

59.1 |

74.3 |

64.6 |

49.7 |

65.1 |

|

12 months |

83.9 |

78.3 |

84.1 |

80.4 |

68.8 |

80.8 |

|

2 years |

88.0 |

79.8 |

88.3 |

64.5 |

54.7 |

64.9 |

Source: Custom report provided by WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Services (CAHS) to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA [unpublished]

Screening for developmental delays using the ASQ questionnaires in regional and remote WA is managed by the WA Country Health Service (WACHS).

In general, a lower proportion of children who attend child health checks in regional and remote WA than in the metropolitan area have a completed ASQ or ASQ:SE.

|

ASQ-3/TRAK (unique clients |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients |

|||

|

Remote and |

Metropolitan area |

Remote and |

Metropolitan area |

|

|

4 months |

66.2 |

73.8 |

52.2 |

64.6 |

|

12 months |

69.9 |

83.9 |

63.0 |

80.4 |

|

2 years |

77.0 |

88.0 |

71.4 |

64.5 |

Source: Custom report provided by WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Services (CAHS) and the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Similar to the metropolitan area, the proportion of Aboriginal children who attend child health checks and whose parents/carers complete an ASQ is lower than that of non-Aboriginal children. The WA Country Health Service have noted that while the ASQ-TRAK is often more culturally appropriate for Aboriginal families, it has been designed to align with the Northern Territory child health schedule which differs from the WA schedule – which may also be a barrier.

Further, the ASQ:SE2 is much less likely to be completed for Aboriginal children. This is likely because there is no ASQ-SE:TRAK version adapted to be culturally appropriate for Aboriginal families and children.

|

ASQ-3/TRAK (unique clients |

ASQ:SE2 (unique clients |

|||||

|

All |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

All |

Aboriginal |

Non-Aboriginal |

|

|

4 month |

66.2 |

50.9 |

69.8 |

52.2 |

33.9 |

55.9 |

|

12 months |

69.9 |

60.9 |

72.9 |

63.0 |

38.1 |

68.2 |

|

2 years |

77.0 |

70.1 |

78.9 |

71.4 |

43.5 |

75.8 |

Source: Custom report provided by the WA Country Health Service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Outcomes of ASQ and ASQ:SE2

Outcomes for children from the ASQ and ASQ:SE2 are tracked. However, as noted above this does not report on outcomes for all children in the Perth Metropolitan area.

This data is not representative of children more broadly as those not attending child health checks and being assessed under the ASQ/ASQ-SE2 may have different characteristics from those that do attend and are assessed.

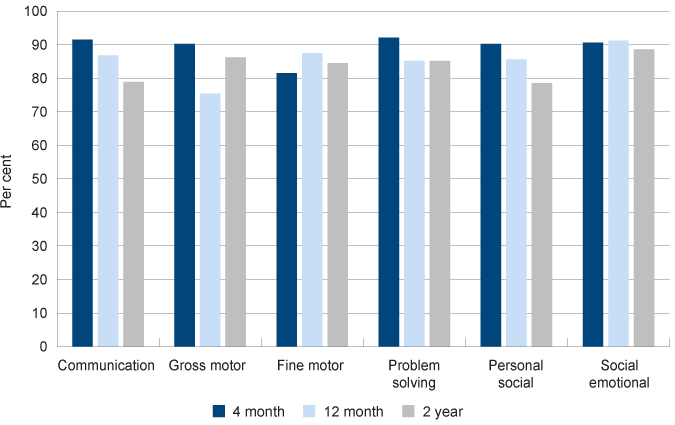

As children age the proportion of children who are categorised as ‘on track’ generally declines. At the four-month check the proportions of children on track for each domain were above 85 per cent, except for fine motor (81.5%). At the 12‑month check the proportions of children on track for each domain were above 80 per cent, except for gross motor skills (75.4%).

|

Communication |

Gross motor |

Fine motor |

Problem solving |

Personal social |

Social emotional |

|

|

4 months |

91.5 |

90.2 |

81.5 |

92.1 |

90.2 |

90.6 |

|

12 months |

86.8 |

75.4 |

87.5 |

85.2 |

85.6 |

91.2 |

|

2 years |

78.9 |

86.2 |

84.5 |

85.2 |

78.5 |

88.6 |

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of children 'on track' based on ASQ by age and domain, per cent, metropolitan Perth, July 2019 to June 2020

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

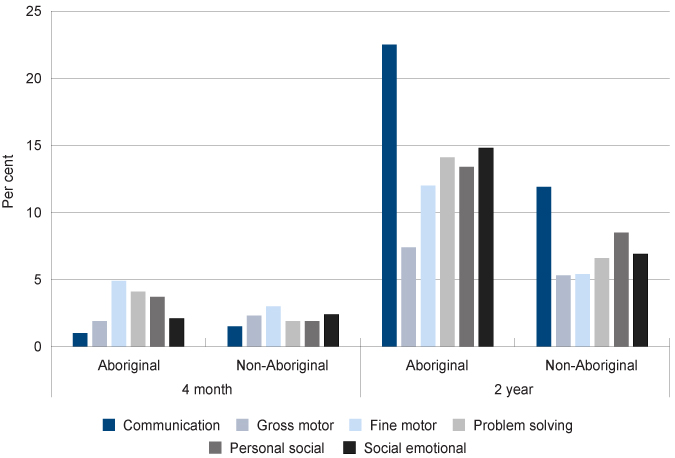

While many Aboriginal children are doing well, multiple and complex disadvantage linked to intergenerational trauma means that Aboriginal children are more likely to be developmentally at risk.

At age four months there was little significant difference between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children across domains. At age two years, the proportion of Aboriginal children identified in the ‘refer’ zone was significantly higher than non-Aboriginal children on communication, problem solving and social emotional domains.

|

Communication |

Gross motor |

Fine motor |

Problem solving |

Personal social |

Social emotional |

||

|

4 months |

Aboriginal |

1.0 |

1.9 |

4.9 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

2.1 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

1.5 |

2.3 |

3.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

|

|

12 months |

Aboriginal |

5.5 |

11.0 |

6.4 |

8.9 |

6.1 |

5.2 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

3.5 |

12.2 |

3.7 |

5.8 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

|

|

2 years |

Aboriginal |

22.5 |

7.4 |

12.0 |

14.1 |

13.4 |

14.8 |

|

Non-Aboriginal |

11.9 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

6.6 |

8.5 |

6.9 |

|

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

* For Aboriginal children the tool may be ASQ-3 or ASQ-TRAK (excluding Social emotional which uses ASQ-SE2)

Proportion of children in the 'refer' zone based on ASQ at 4 months and 2 years by Aboriginal status, per cent, metropolitan Perth, July 2019 to June 2020

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

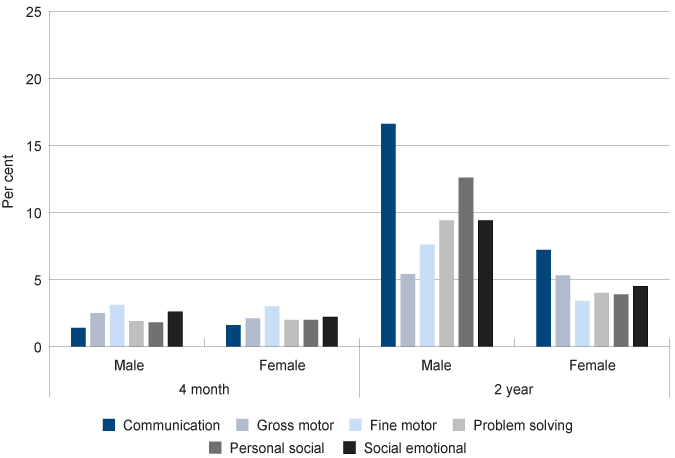

The ASQ data is also available by gender. As with the AEDC data (refer to indicator Readiness for learning) male children are more likely to be at risk of developmental issues across most domains than female children.

|

Communication |

Gross motor |

Fine motor |

Problem solving |

Personal social |

Social emotional |

||

|

4 months |

Male |

1.4 |

2.5 |

3.1 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

2.6 |

|

Female |

1.6 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

|

12 months |

Male |

4.8 |

11.8 |

4.3 |

6.8 |

5.4 |

5.3 |

|

Female |

2.2 |

12.5 |

3.3 |

4.9 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

|

|

2 years |

Male |

16.6 |

5.4 |

7.6 |

9.4 |

12.6 |

9.4 |

|

Female |

7.2 |

5.3 |

3.4 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

|

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

Proportion of children in the 'refer' zone based on ASQ at 4 months and 2 years by gender, per cent, metropolitan Perth, July 2019 to June 2020

Source: Custom report provided by the Child and Adolescent Health service to the Commissioner for Children and Young People [unpublished]

At age 4 months there is little difference between the outcomes for male and female children. By age two years, the proportion of male children recommended for referral was significantly higher than female children on all domains, except gross motor.

The reason for differences between the development of male and female children is complex and often contested.12 There is evidence to suggest that male children mature at a slower rate and may develop language and communication skills later than female children.13,14 There is also some evidence to suggest that social interactions start to influence differences at an early age.15

No data was available on results of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires® for children in regional and remote WA for the 2019-20 year, however it is anticipated these will be available for the 2020-21 period.

One preventable condition that impacts an unknown number of WA children is Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) which is a ‘hidden’ disability, and easily confused with disobedience or conditions such as ADHD.16 FASD is an umbrella term which covers a range of possible birth defects and/or developmental disabilities that can be caused by exposure to alcohol prior to birth. It has a significant impact on mental health and increases the likelihood of social and emotional behavioural issues throughout life.17,18,19

In 2017, a Telethon Kids Institute research team found that 89 per cent of young people in WA’s Banksia Hill Detention Centre had at least one form of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, while 36 per cent were found to have FASD. Only two of the young people with FASD had been diagnosed prior to participation in the study.21

The Royal Australian College of Physicians note that it is highly likely there is substantial under-diagnosis of FASD more broadly due to a lack of awareness by clinicians and a fear of stigmatising families and children.22

This highlights the importance of early identification of developmental issues through health and developmental checks, particularly for vulnerable children.

Endnotes

- Oberklaid F and Drever K 2011, Is my child normal? Milestones and red flags for referral, Australian Family Physician, Vol 40, No 9, September 2011.

- The ASQ is a tool for individual screening of children two years and under. This is in contrast to the Australian Early Development Census, which covers similar domains, however is a tool to provide policy makers and communities with information on children’s developmental outcomes at the community level. The AEDC is not used for individual screening or referral of children.

- Feeney-Kettler KA 2010, Screening Young Children’s Risk for Mental Health Problems: A Review of Four Measures, Assessment for Effective Intervention, Vol 35, No 4.

- Yoong T et al 2015, Is the Australian Developmental Screening Test (ADST) a useful step following the completion of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) on the pathway to diagnostic assessment for young children?, Australian Journal of Child and Family Health Nursing, Vol 12, No 1.

- Community Health services in WA use the Ages and Stages Questionnaires®, Third Edition (ASQ-3), the Ages and Stages Questionnaires®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2) and in some country health services ASQ TRAK is used. Source: WA Department of Health: Community Health Manual – Ages and Stages Questionnaire.

- Stensen K et al 2018, Screening for mental health problems in a Norwegian preschool population. A validation of the ages and stages questionnaire: Social-emotional (ASQ:SE), Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Vol 23, No 4.

- D’Aprano A et al 2016, Adaptation of the Ages and Stages Questionnaire for Remote Aboriginal Australia, Qualitative Health Research, Vol 26, No 5.

- D’Aprano A et al 2020, Practitioners’ perceptions of the ASQ-TRAK developmental screening tool for use in Aboriginal children: A preliminary survey, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, Vol 56, No 1.

- Brookes Publishing 2013, Guidelines for Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation of ASQ-3™ and ASQ:SE, Brookes Publishing [online].

- D’Aprano A et al 2020, Practitioners’ perceptions of the ASQ-TRAK developmental screening tool for use in Aboriginal children: A preliminary survey, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, Vol 56, No 1.

- Child and Adolescent Health Service 2021, Community Health Clinical Nursing Manual – Guidelines: Ages and Stages Questionnaires, WA Department of Health.

- Kinnell A et al 2013, Boys and girls in South Australia: A comparison of gender differences from the early years to adulthood, Fraser Mustard Centre, Department for Education and Child Development and Telethon Kids Institute.

- Etchell A et al 2018, A systematic literature review of sex differences in childhood language and brain development, Neuropsychologia, Vol 114, pp. 19–31.

- Brinkman SA et al 2012, Jurisdictional, socioeconomic and gender inequalities in child health and development: analysis of a national census of 5-year-olds in Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 2, No 5.

- Kinnell A et al 2013, Boys and girls in South Australia: A comparison of gender differences from the early years to adulthood, Fraser Mustard Centre, Department for Education and Child Development and Telethon Kids Institute, p. 28.

- McLean S and McDougall S 2014, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Current issues in awareness, prevention and intervention, CFCA Paper No 20, Child Family Community Australia (CFCA).

- Brown J et al 2018, Fetal Alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD): A beginner’s guide for mental health professionals, Journal of Neurological Clinical Neuroscience, Vol 2, No 1.

- Pei J et al 2011, Mental health issues in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, Journal Of Mental Health, Vol 20, No 5, pp. 438–448.

- Hamilton S et al 2021, Review of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, Vol 2, No 1.

- Bower C et al 2017, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study amount young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia, BMJ Open, Vol 8, No 2.

- Royal Australian College of Physicians 2018, RACP Submission: Consultation on the Australian Draft National Alcohol Strategy 2018-2026, p. 19.

Last updated February 2022

There is limited data available on the number of WA children in care aged 0 to five years who have received an initial medical examination or ongoing health assessment, or who have identified developmental issues.

At 30 June 2021 there were 1,536 WA children in care aged between 0 and five years, more than half of whom (61.3%) were Aboriginal.1

Children in care are more likely than the general population to have poor physical, mental and developmental health.2 Experts recommend that for the best optimal care, all children entering care should have a comprehensive assessment of their health within 30 days of placement.3

Standard five of the National Standards for Children in out-of-home care states that children and young people should have their physical, developmental, psychosocial and mental health needs assessed and attended to in a timely way.4

The WA Department of Communities casework practice manual requires that all children entering the WA out-of-home care system receive an initial medical examination by a general practitioner or other health professional within 20 days, and that they have an ongoing annual health assessment.5 The health provider is nominated by the Department of Communities and can include an Aboriginal Medical Service, general practitioner or a community health nurse. The Department of Health (Child and Adolescent Health Service) monitors the health and development assessments of children in care conducted by metropolitan community health nurses.

In 2016, the WA Department of Child Protection (now Department of Communities) published the Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015–16 Baseline Indicator Report. The outcomes framework identified two indicators related to reviewing the physical health of children in out-of-home care.

The first indicator was the ‘proportion of children who had an initial medical examination when entering out-of-home care’. In 2015, 53.1 per cent of children entering out-of-home care had an initial medical examination.6

The second indicator was the ‘proportion of children who have had an annual health check of their physical development.’ In this report they noted that there were limitations in data accuracy which prevented reporting on this indicator in 2015–16; however, data would be reported in 2016–17.7

No more recent data has been reported by the Department of Communities as at publication date.

The low proportion of children provided with an initial medical examination in 2015 and lack of publicly available data on whether all children in care are receiving these essential checks needs to be urgently addressed.

The Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study (POCLS) is a longitudinal study on out-of-home care which examines the developmental wellbeing of children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in NSW.8 To measure the children’s development the research team used the ASQ-3 for children from nine to 66 months of age.

Preliminary findings from this study show that more than 80 per cent of the children were generally developing normally. However, Aboriginal children aged three to five years tended to show higher atypical development across all domains.9 In the area of socio-emotional wellbeing, the study showed behavioural problems for all children increasing with age from 17 per cent among 12 to 35 month-olds to 47 per cent among 12 to 17 year-olds.10 Children in residential care appeared to experience poorer wellbeing outcomes than other placement types, such as kinship care.11

Endnotes

- Department of Communities 2021, Custom report provided by Department of Communities, WA Government [unpublished].

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2006, Health of children in “out-of-home” care, RACP.

- Ibid.

- Department of Social Services 2011, An outline of the National Standards for out-of-home care, Australian Government.

- Department of Child Protection and Family Support (Communities), Casework Practice Manual: Healthcare Planning, WA Government.

- Department for Child Protection and Family Support 2016, Outcomes Framework for Children in Out-of-Home Care 2015–16 Baseline Indicator Report, p. 5.

- Ibid, p. 10.

- Australian Institute of Family Studies, Chapin Hall Center for Children University of Chicago and New South Wales Department of Family and Community Services 2015, Pathways of Care Longitudinal Study: Outcomes of children and young people in Out-of-Home care in NSW Wave 1 baseline statistical report, NSW Department of Family and Community Services.

- Ibid, p. 113.

- Ibid, p. 123.

- Ibid, p. 124.

Last updated February 2022

Early childhood health and development checks can often identify children with potential disability or developmental issues. A child who presents with possible disability through this process will be referred to Child Development Services for further assessment.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates 9,000 WA children aged 0 to five years (4.4%) had reported disability in 2018.1

The types of disability that affect children vary somewhat with age. This is in part because as children age, developmental difficulties in certain areas (such as intellectual capacity) become more apparent. Furthermore, there is a lack of formal intellectual testing in very young children.2

Of Australian young children aged 0 to five years who have disability, almost two-thirds (69.9%) have a sensory (e.g. sight and hearing) or speech disability. Older children aged six to 11 years are more likely than younger children to have an intellectual disability (67.8% compared to 32.0%).3

Endnotes

- Data is sourced from a custom report provided to the Commissioner for Children and Young People WA by the Australian Bureau of Statistics based on the 2018 Disability, Ageing and Carers survey. The ABS uses the following definition of disability: ‘In the context of health experience, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICFDH) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In this survey, a person has a disability if they report they have a limitation, restriction or impairment, which has lasted, or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities’. Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016, Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, 2015, Glossary.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2013, Australian Social Trends: 2012, Children with a disability, ABS catalogue no. 4102.0, Commonwealth of Australia, p. 3.

- Ibid.

Last updated February 2022

Early childhood is the most effective time to intervene in the health, development and wellbeing of children and has the greatest potential to prevent or lessen problems in later childhood, adolescence and adulthood.

Child health checks and developmental screening through the Ages and Stages Questionnaires® (ASQ) are key mechanisms to improve child health outcomes through early identification of developmental issues.

In 2010, the WA Auditor General reviewed the WA Department of Health’s universal health check system and found that many children were missing out on checks.1 In 2014, the Auditor General performed a follow-up review and found that while the Department had increased the number of health checks being performed, they were still not keeping up with the growth in demand.2

Recommendations from the Auditor General’s 2014 report included extending access to child health centres through more flexible opening hours, sending appointment reminders to parents and possibly implementing an online booking system.3

The Child and Adolescent Health Service in metropolitan Perth and the WA Country Health Service have implemented changes to provide a more flexible approach. In metropolitan Perth this has meant the addition of drop-in sessions as an alternative to the Universal checks. In regional and remote locations the updated schedule has also been implemented, however services are historically more informal with higher rates of drop-in contacts and visits in-between Universal checks.

Service availability and accessibility is a key issue in remote and regional locations. The WA Country Health Service has implemented changes with the aim of improving availability, the effectiveness of these changes will be monitored in future data updates for this measure.

While most children in WA are receiving the initial child health check after birth, regardless of the service changes, many children are still not receiving the later child health checks, particularly the 12-month and two-year checks. These checks are essential to identify developmental issues related to speech and language and children who miss these checks are at risk of not being ready for school.4

The Child and Adolescent Health Service in metropolitan Perth are implementing strategies to improve attendance at the later universal child health checks, including a communication and awareness raising campaign, identification and targeted follow-up of ‘at-risk’ children, outreach programs and a range of ICT initiatives.

Attending child health checks is only a first step – if a child is identified as having a potential health or developmental issue it is critical that they are referred for further diagnosis and, if necessary, they receive appropriate treatment and services. The ongoing issue of a lack of accessible child development services and long waiting times means that many children are missing out.

Ages and Stages questionnaires®

The results of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires® (ASQ) in metropolitan Perth show that many children in Perth are ‘on track’ developmentally. However, a significant proportion of parents are not completing the ASQ for their children.

Additionally, of those children with ASQ results, a relatively high proportion are identified as possibly having a developmental delay and are recommended for either monitoring or referral. For example, in 2019–20, 21.1 per cent and 21.5 per cent of Perth metropolitan children aged two years were recommended for monitoring or referral in the communication domain and the personal social domain, respectively.

Some experts note that tools such as the ASQ miss a large number of children with mild to moderate developmental issues and may incorrectly identify children whose development is normal.5 They recommend a broader approach to developmental reviews by integrating surveillance into primary health care, so that every encounter a health professional has with a child is an opportunity to consider their developmental progress. Thus, general practitioners, not only child health professionals, need to have a good understanding of normal child development and should review developmental progress at each contact.6

Aboriginal children are at a higher risk of experiencing developmental issues in childhood and into adulthood.7 Yet, evidence suggests that universal mainstream child health services are under-used by many within the Aboriginal population.8 The data in this section confirms that Aboriginal children across WA were less likely to attend child health checks and less likely to have ASQ questionnaires completed on their behalf.

Health in early childhood is a key determinant of risk of chronic diseases over the lifetime.9 Life expectancy at birth for Aboriginal people in Australia in 2015–2017 was 71.6 years for men and 75.6 years for women. This is in contrast with 80.2 years for non-Aboriginal men and 83.4 years for non-Aboriginal women.10 The leading causes of higher mortality for Aboriginal people were chronic diseases including circulatory disease, cancer, diabetes and respiratory disease.11

Socio-economic disadvantage, including parental income levels, education and access to health services have a significant influence on health in childhood.12 The data supports this finding, as Aboriginal peoples living in the most disadvantaged areas - a higher proportion of whom are living in remote Australia - have the lowest life expectancy.13

A critical component of improving Aboriginal people’s health and wellbeing over the longer term is to ensure Aboriginal children are assessed for health and development issues and, where necessary, referred to high quality, culturally safe services as early as possible.

Research highlights that Aboriginal mothers continue to have negative experiences with some health services, in part due to a lack of cultural awareness on the part of the service providers.14,15 It is essential that health services focus on improving their engagement with Aboriginal families and in particular, implementing culturally safe practices.16,17,18 As part of this, there is a clear need for culturally and developmentally appropriate ASQ-TRAK questionnaires (or equivalent) to be developed for Aboriginal children and families using WA Aboriginal languages and the WA child health check schedule.

Data gaps

While attending child health checks is critical, children must also receive appropriate services for any issues identified. Referral and outcomes data for each child is captured in the Perth metropolitan area through the Child Development Information System (CDIS) and this is used by the child health nurse for follow-up as required.

In regional and remote WA, referral data is captured on individual child health referrals, however this data was not able to be collated due to disparate systems. Similarly, no data is yet available on the results of the Ages and Stages Questionnaires® (ASQ) for children in regional and remote WA. WA Country Health Service is now using a single data collection system but requires some standardisation before ASQ results can be reported. It is anticipated these will be available for the 2020-21 period.

The limited data being collected and reported on the physical health of WA children in care is of concern. That 53.1 per cent of children entering out-of-home care had an initial medical examination in 2015 and the lack of publicly available data needs to be urgently addressed.

Children in care are more likely than the general population to have poor physical, mental and developmental health,19 it is therefore essential that they receive appropriate health and developmental checks on entry into care and on a regular basis thereafter.

Endnotes

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Report 11, November 2010.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2014, Universal Child Health Checks Follow-up, Report 10, June 2014.

- Office of the Auditor General WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Report 11, November 2010, p. 20.

- Oberklaid F and Drever K 2011, Is my child normal? Milestones and red flags for referral, Australian Family Physician, Vol 40, No 9, September 2011.

- Ibid.

- Wise S 2013, Improving the early life outcomes of Indigenous children: implementing early childhood development at the local level, Closing the Gap Clearing House, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

- WA Department of Health, Child and Adolescent Health Service 2018, Community Health Manual: Aboriginal Child Health, WA Government.

- Campbell F et al 2014, Early Childhood Investments Substantially Boost Adult Health, Science, Vol. 343, No. 6178, pp. 1478–1485.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2018, Life Tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, ABS.

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2018, Closing the Gap: Prime Minister’s Report 2018, Australian Government, p. 105.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2017, Australia’s Health 2016: 4.2 Social determinants of Indigenous health, AIHW.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2018, 3302.0 Life Tables for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2015–2017, ABS.

- Brown et al 2016, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's experiences accessing standard hospital care for birth in South Australia – A phenomenological study, Women and Birth, Vol 29 No 4.

- Bar-Zeev et al 2014, Factors affecting the quality of antenatal care provided to remote dwelling Aboriginal women in northern Australia, Midwifery, Vol 30.

- Wilson G 2009, What do Aboriginal Women Think is Good Antental Care? Consultation Report, Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Inc. and Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health,

- Telethon Institute for Child Health Research 2009, Overview and Summary Report of Antenatal Services Audit for Aboriginal Women and Assessment of Aboriginal Content in Health Education in Western Australia.

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council 2017, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Standing Committee 2015, Cultural Respect Framework 2016 – 2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health: A National Approach to Building a Culturally Respectful Health System, Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council.

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) 2006, Health of children in “out-of-home” care, RACP.

For more information on early childhood health and development screening refer to the following resources:

- Auditor General for WA 2010, Universal Child Health Checks, Office of Auditor General WA.

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council 2011, National Framework for Universal Child and Family Health Services, Australian Government.

- McLean K et al 2014, Screening and surveillance in early childhood health: Rapid review of evidence for effectiveness and efficiency of models, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Moore TG et al 2017, The First Thousand Days: An Evidence Paper – Summary, Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

- Oberklaid F and Drever K 2011, Is my child normal? Milestones and red flags for referral, Australian Family Physician, Vol 40, No 9.

- Wise S 2013, Improving the early life outcomes of Indigenous children: implementing early childhood development at the local level, Closing the Gap Clearing House, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).